Summary

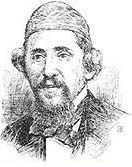

Israe͏̈l Joseph Benjamin (Fălticeni, Moldavia, 1818 – London, May 3, 1864) was a Romanian-Jewish historian and traveler. His pen name was "Benjamin II", in allusion to Benjamin of Tudela.

Life and travels edit

Married young, he engaged in the lumber business, but losing his modest fortune, he gave up commerce. Being of an adventurous disposition, he used the name of Benjamin of Tudela, the famous twelfth-century Jewish traveler, and set out in 1844 on a search for the Lost Ten Tribes of Israel. This search took him from Vienna to Constantinople in 1845, with stops at several cities on the Mediterranean. He arrived in Alexandria in June, 1847, and proceeded via Cairo to the Levant. He then traveled through Syria, Babylonia, Kurdistan, Persia, the Indies, Kabul, and Afghanistan, returning in June 1851, to Constantinople, and then back to Vienna, where he stayed briefly before heading to Italy. There he embarked for Algeria and Morocco. He made copious notes of his observations of the societies he visited.

On arriving in France, after having traveled for eight years, he prepared in Hebrew his impressions of travel, and had the book translated into French. After suffering many tribulations in obtaining subscriptions for his book, he issued it in 1856, under the title Cinq Années en Orient (1846–51). The same work, revised and enlarged, was subsequently published in German under the title Acht Jahre in Asien und Afrika (Hanover, 1858), with a preface by Meyer Kayserling. An English version has also been published. As the veracity of his accounts and the genuineness of his travels were attacked by some critics, he amply defended himself by producing letters and other tokens proving his journey to the various Oriental countries named. Benjamin relates only what he has seen; and, although some of his remarks show insufficient scholarship and lack of scientific method, his truthful and simple narrative gained the approval of eminent scholars like Humboldt, Petermann, and Richter.

In 1859 Benjamin undertook another journey, this time to America, where he stayed three years. The result of his observations there he published on his return, under the title Drei Jahre in Amerika (Hanover, 1863). The kings of Sweden and of Hanover now conferred distinctions upon him. Encouraged by the sympathy of several scientists, who drew up a plan and a series of suggestions for his guidance, he determined to go again to Asia and Africa, and went to London in order to raise funds for this journey — a journey which was not to be undertaken. Worn out by fatigues and privations, which had caused him to grow old before his time and gave him the appearance of age, he died poor in London; and his friends and admirers had to arrange a public subscription in order to save his wife and daughter from misery.

In addition to the works mentioned above, Benjamin published Jawan Mezula, Schilderung des Polnisch-Kosakischen Krieges und der Leiden der Juden in Poland Während der Jahre 1648-53, Bericht eines Zeitgenossen nach einer von. L. Lelewel Durchgesehenen Französischen Uebersetzung, Herausgegeben von J. J. Benjamin II., Hanover, 1863, a German edition of Rabbi Nathan Nata Hanover's work on the insurrection of the Cossacks in the seventeenth century, with a preface by Kayserling.

Notes from J.J. Benjamin's travels edit

In his Cinq années de voyage en Orient, 1846-1851, J. J. Benjamin wrote down some observations on the life of the Jews in Persia which have been quoted by modern writers:[1][2]

- 1. Throughout Persia the Jews are obliged to live in a part of the town separated from the other inhabitants; for they are considered as unclean creatures, who bring contamination with their intercourse and presence.

- 2. They have no right to carry on trade in stuff goods.

- 3. Even in the streets of their own quarter of the town they are not allowed to keep any open shop. They may only sell there spices and drugs, or carry on the trade of a jeweler, in which they have attained great perfection.

- 4. Under the pretext of their being unclean, they are treated with the greatest severity, and should they enter a street, inhabited by Mussulmans, they are pelted by the boys and mobs with stones and dirt.

- 5. For the same reason they are forbidden to go out when it rains; for it is said the rain would wash dirt off them, which would sully the feet of the Mussulmans.

- 6. If a Jew is recognized as such in the streets, he is subjected to the greatest insults. The passers-by spit in his face, and sometimes beat him so unmercifully, that he falls to the ground, and is obliged to be carried home.

- 7. If a Persian kills a Jew, and the family of the deceased can bring forward two Mussulmans as witnesses to the fact, the murderer is punished by a fine of 12 tumauns (600 piastres); but if two such witnesses cannot be produced, the crime remains unpunished, even though it has been publicly committed, and is well known.

- 8. The flesh of the animals slaughtered according to Hebrew custom, but declared as Trefe, must not be sold to any Mussulmans. The slaughterers are compelled to bury the meat, for even the Christians do not venture to buy it, fearing the mockery and insult of the Persians.

- 9. If a Jew enters a shop to buy anything, he is forbidden to inspect the goods, but must stand at a respectful distance and ask the price. Should his hand incautiously touch the goods, he must take them at any price the seller chooses to ask for them.

- 10. Sometimes the Persians intrude into the dwellings of the Jews and take possession of whatever pleases them. Should the owner make the least opposition in defense of his property, he incurs the danger of atoning for it with his life.

- 11. Upon the least dispute between a Jew and a Persian, the former is immediately dragged before the Achund [religious authority], and, if the complainant can bring forward two witnesses, the Jew is condemned to pay a heavy fine. If he is too poor to pay this penalty in money, he must pay it in his person. He is stripped to the waist, bound to a stake, and receives forty blows with a stick. Should the sufferer utter the least cry of pain during this proceeding, the blows already given are not counted, and the punishment is begun afresh.

- 12. In the same manner the Jewish children, when they get into a quarrel with those of the Mussulmans, are immediately led before the Achund, and punished with blows.

- 13. A Jew who travels in Persia is taxed in every inn and every caravanserai he enters. If he hesitates to satisfy any demands that may happen to be made on him, they fall upon him, and maltreat him until he yields to their terms.

- 14. If, as already mentioned, a Jew shows himself in the street during the three days of the Katel (qatl al-Husayn "murder of Husayn", commemoration by Shi'ites of the assassination of Husayn ibn Ali) he is sure to be murdered.

- 15. Daily and hourly new suspicions are raised against the Jews, in order to obtain excuses for fresh extortions; the desire of gain is always the chief incitement to fanaticism.

Bibliography in English edit

- Five years in the Orient (1846–51)

- Eight years in Asia and Africa (Hanover, 1858)

- Description of the Polish-Cossack war and of the suffering the Jews in Poland during the years 1648-53

- Report of a contemporary of L Lelewel examining his French translations, edited by J. J. Benjamin II (Hanover, 1863)

- A German edition of Rabbi Nathan Nata Hanover's work on the insurrection of the Cossacks in the seventeenth century.

- Three Years in America (3 vols.) (Hanover, 1862)

References edit

- ^ Israel Joseph Benjamin (1856). Cinq années de voyage en Orient, 1846-1851. Michel Levy frères. pp. 160–.

- ^ Translated from the French by Bernard Lewis, The Jews of Islam. Princeton University Press, 1984. Chapter "The End of Tradition", pp. 181–183