Summary

James Guillaume (1844–1916) was a leading member of the Jura federation, the anarchist wing of the First International. Later, Guillaume would take an active role in the founding of the Anarchist St. Imier International.[1]

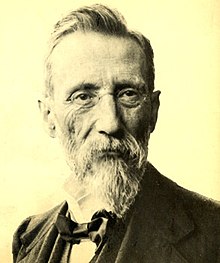

James Guillaume | |

|---|---|

James Guillaume (date unknown) | |

| Born | 16 February 1844 |

| Died | 20 November 1916 (aged 72) |

| Resting place | Montparnasse Cemetery |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, historian |

| Organization | International Workingmen's Association |

| Movement | Anarchism |

Life edit

Guillaume was born in London on 16 February 1844, the son of George Guillaume and his wife Marie Suzanne Glady.[2] George Guillaume ran the London branch of a Neuchâtel watchmaking factory.[3] His brother, also named George, would later become a communard.[3] The family returned to Switzerland in 1848.[3]

From 1862-1864, he studied at the University of Zurich, but did not complete his degree; he acquired a teaching diploma from Neuchâtel in 1865.[2] He taught in Le Locle from 1864, as a professor of French and history.[3] There, he and Constant Meuron founded the local section of the International in 1866.[2] He was active in the foundation of the Jura Federation, which led to his expulsion from the First International.[2]

His political activities resulted in his dismissal from teaching in 1869, and he turned to operating his father's printing business until 1872.[3] He became editor of La Solidarité in April 1870, and edited Bulletin de la Fédération jurassienne from February 1872 until March 1878.[3]

After his prosecution following demonstrations in Bern in 1877, he moved to Paris and served as editor for various academic projects: Ferdinand Buisson's Dictionnaire de pédagogie, Revue pédagogique, and Dictionnaire géographique et administratif de la France.[2]

His daughter Marguerite died in 1897.[2] Subsequently, Guillaume stayed at the psychiatric hospital of Waldau in Bern until 1898, then Neuchâtel until 1901.[2] His wife, Elise Golay (married 1870)[2] died in 1901.[3]

A meeting with Jean Jaurès prompted his return to politics. He was unimpressed by the direction socialism had taken, and favoured the direct action of syndicalists like the CNT.[2] With Max Nettlau, he published six volumes of Bakunin's writings; he also edited L’Internationale, documents et souvenirs, 1864-1878 (Paris, 1905-1910).[3]

Guillaume left Paris in December 1914 to seek treatment in the Préfargier mental hospital in Neuchâtel, where he died on 20 November 1916.[2]

Work edit

In his 1876 essay, "Ideas on Social Organization," Guillaume set forth his opinions regarding the form that society would take in a post-revolutionary world, expressing the collectivist anarchist position he shared with Bakunin and other anti-authoritarians involved in the First International:

- Whatever items are produced by collective labor will belong to the community, and each member will receive remuneration for [their] labor either in the form of commodities (subsistence, supplies, clothing, etc.) or in currency.

Only later, he believed, would it be possible to progress to a communist system where distribution will be according to need:

- When, thanks to the progress of scientific industry and agriculture, production comes to outstrip consumption, and this will be attained some years after the Revolution, it will no longer be necessary to stingily dole out each worker’s share of goods. Everyone will draw what [they] need from the abundant social reserve of commodities, without fear of depletion; and the moral sentiment which will be more highly developed among free and equal workers will prevent, or greatly reduce, abuse and waste.[4]

In 1909, James Guillaume assisted Peter Kropotkin with the research in preparing his book, "The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793," particularly helping with regards to the resolutions (arrêtés) of 4 August 1789, where the Assembly declared that it is acting with both constituent and legislative power.[5] Guillaume is said to have played a key role in Peter Kropotkin's conversion to anarchism.

Writings edit

- L'Internationale: Documents et Souvenirs (1864–1878), 4 vols., reprinted in 1969 by Burt Franklin Publishing, New York.

- Ideas on Social Organization

- Pestalozzi : étude biographique (1890), Hachette, Paris.

- Michael Bakunin, a Biography (1907)

- Karl Marx, pangermaniste, et l’Association internationale des travailleurs de 1864 à 1870 (1915), A. Colin, Paris.

He also edited five of the six volumes of Bakunin's collected works (in French), which included the first biography of Bakunin.[6]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ "Black Rose Books". Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gigandet, Cyrille (13 October 2008). "James Guillaume". DHS - Dictionnaire Historique de la Suisse (in French). Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Maitron, Jean; Enckell, Marianne (18 October 2022), "GUILLAUME James", Dictionnaire des anarchistes (in French), Paris: Maitron/Editions de l'Atelier, retrieved 22 January 2024

- ^ Marxists Internet Archives, Guillaume Archive

- ^ Peter Kropotkin (1909). "Preface". The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793. Translated by N. F. Dryhurst. New York: Vanguard Printings.

- ^ Marxists Internet Archives, Bakunin Archive

Archive sources edit

Part of James Guillaume's archives are conserved in the "Archives de l'État de Neuchâtel". The collection contains correspondence, notes, articles and memorabilia.

- GUILLAUME JAMES, Fonds: James Guillaume. Archives de l'État de Neuchâtel.

External links edit

- About James Guillaume

- Anarchy Archives, Guillaume page

- A research blog dedicated to James Guillaume : http://jguillaume.hypotheses.org/

- James Guillaume Works

- James Guillaume Archive at Marxists.org

- James Guillaume Archive at TheAnarchistLibrary.org

- James Guillaume Archive at RevoltLib.com

- Archive of James Guillaume Papers at the International Institute of Social History