Summary

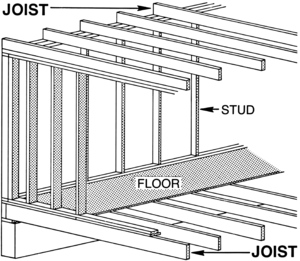

A joist is a horizontal structural member used in framing to span an open space, often between beams that subsequently transfer loads to vertical members. When incorporated into a floor framing system, joists serve to provide stiffness to the subfloor sheathing, allowing it to function as a horizontal diaphragm. Joists are often doubled or tripled, placed side by side, where conditions warrant, such as where wall partitions require support.

Joists are either made of wood, engineered wood, or steel, each of which has unique characteristics. Typically, wood joists have the cross section of a plank with the longer faces positioned vertically. However, engineered wood joists may have a cross section resembling the Roman capital letter "I"; these joists are referred to as I-joists. Steel joists can take on various shapes, resembling the Roman capital letters "C", "I", "L" and "S".

Wood joists were also used in old-style timber framing. The invention of the circular saw for use in modern sawmills has made it possible to fabricate wood joists as dimensional lumber.

Strength characteristics edit

Joists must exhibit the strength to support the anticipated load over a long period of time. In many countries, the fabrication and installation of all framing members including joists must meet building code standards. Considering the cross section of a typical joist, the overall depth of the joist is critical in establishing a safe and stable floor or ceiling system. The wider the spacing between the joists, the deeper the joist needs to be to limit stress and deflection under load. Lateral support called dwang,[1] blocking,[2] or strutting[2] increases its stability, preventing the joist from buckling under load. There are approved formulas for calculating the depth required and reducing the depth as needed; however, a rule of thumb for calculating the depth of a wooden floor joist for a residential property is to take half the span in feet, add two, and use the resulting number as the depth in inches; for example, the joist depth required for a 14-foot (4.3 m) span is 9 inches (230 mm). Many steel joist manufacturers supply load tables to allow designers to select the proper joist sizes for their projects.

Standard dimensional lumber joists have their limitations due to the limits of what farmed lumber can provide. Engineered wood products such as I-joists gain strength from expanding the overall depth of the joist, as well as by providing high-quality engineered wood for both the bottom and the top chords of the joist. A common saying regarding structural design is that "deeper is cheaper", referring to the more cost-effective design of a given structure by using deeper but more expensive joists, because fewer joists are needed and longer spans are achieved, which more than makes up for the added cost of deeper joists.

Types edit

In traditional timber framing there may be a single set of joists which carry both a floor and ceiling called a single floor (single joist floor, single framed floor) or two sets of joists, one carrying the floor and another carrying the ceiling called a double floor (double framed floor). The term binding joist is sometimes used to describe beams at floor level running perpendicular to the ridge of a gable roof and joined to the intermediate posts. Joists which land on a binding joist are called bridging joists.[3][4] A large beam in the ceiling of a room carrying joists is a summer beam. A ceiling joist may be installed flush with the bottom of the beam or sometimes below the beam. Joists left exposed and visible from below are called "naked flooring" or "articulated" (a modern U.S. term) and were typically planed smooth (wrought) and sometimes chamfered or beaded.

Connections to supporting beams edit

Joists may join to their supporting beams in many ways: joists resting on top of the supporting beams are said to be "lodged"; dropped in using a butt cog joint (a type of lap joint), half-dovetail butt cog, or a half-dovetail lap joint. Joists may also be tenoned in during the raising with a soffit tenon or a tusk tenon (possibly with a housing). Joists can also be joined by being slipped into mortises after the beams are in place such as a chase mortise (pulley mortise), L-mortise, or "short joist". Also, in some Dutch-American work, ground level joists are placed on a foundation and then a sill placed on top of the joists such as what timber frame builder Jack Sobon called an "inverted sill" or with a "plank sill".

Joists can have different joints on either ends such as being tenoned on one end and lodged on the other end. A reduction in the under-side of cogged joist-ends may be square, sloped or curved. Typically joists do not tie the beams together, but sometimes they are pinned or designed to hold under tension. Joists on the ground floor were sometimes a pole (pole joist, half-round joist, log joist. A round timber with one flat surface) and in barns long joists were sometimes supported on a sleeper (a timber not joined to but supporting other beams). Joists left out of an area form an opening called a "well" as in a stairwell or chimney-well. The joists forming the well are the heading joist (header) and trimming joist (trimmer). Trimmers take the name of the feature such as hearth trimmer, stair trimmer, etc.

Shortened joists are said to be crippled. The term rim joist is rare before the 1940s in America; it forms the edge of a floor. The outermost joist in half timber construction may be of a more durable species than the interior joists. In a barn, loose poles above the drive floor are called a scaffold. Between the joists, the area called a joist-bay, and above the ceiling in some old houses is material called pugging, which was used to deaden sound, insulate, and resist the spread of fire.

In platform framing, the joists may be connected to the rim joist with toenailing or by using a joist hanger.[5]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Fleming, Eric. Construction technology: an illustrated introduction. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. 105. Print.

- ^ a b Emmitt, Stephen, R. Barry, and Christopher A. Gorse. Barry's advanced construction of buildings. 2nd ed. Chichester, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. 3-94. Print.

- ^ John Henry Parker A Glossary of Terms used in the Grecian, Roman, Italian and Gothic Architecture (1840)

- ^ "joist" def. 1. Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) Oxford University Press (2009)

- ^ "Joist Hangers vs End-Nailing vs Toe Nailing for Deck: Which Is Better?". plasticinehouse.com. 30 August 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2021.