Summary

Joseph Pâris dit Duverney or Joseph Pâris Du Verney (10 April 1684 – 17 July 1770) (the suffix "Duverney" comes from an estate at Moirans which belonged to his family) was a French financier.

Joseph Paris Duverney | |

|---|---|

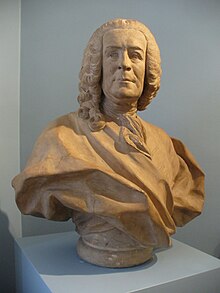

Bust of Pâris-Duverney in musée de Brunoy | |

| Born | 10 April 1684 Moirans, France |

| Died | 17 July 1770 (aged 86) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Banker |

Early life and career edit

The third of four brothers, he joined them in Paris at the age of seventeen and, after a brief period in the Gardes Françaises he followed the example of his elder brothers by going into business provisioning the army. He served as Quartermaster at Mons, then as Director General of Provisions from 1706–9. He became Munitioner-General in 1710, acquired the tax farm for tobacco in 1714 and, together with his brothers, bought into the ferme générale in 1718. He was involved in a project to develop Louisiana. The Pâris brothers obtained a concession not far from New Orleans and established a plantation there. Because of their criticisms of John Law, the brothers were exiled to the Dauphiné in June 1720,[1] just a month before the bursting of the Mississippi Bubble. Supported by Antoine Crozat and Samuel Bernard, two other former financiers of Louis XIV, the brothers undertook to manage the consequences of the collapse of Law system. In particular, Pâris-Duverney directed l'opération du visa - the systematic management of payments to bondholders.

In December 1721, he acquired the lordship of Plaisance (near Nogent) and undertook the reconstruction of the château there, turning it into a residence designed according to his own specifications.

Under the ministry of the Duke of Bourbon, in which he served as principal secretary, he enjoyed the support of the Marquise de Prie and proposed a new tax, the 'cinquantième' (2% levy)[2] as well as a number of measures which provoked the opposition of both the Parlement of Paris and the nobility. His growing unpopularity led to an assassination attempt on him, followed by a second fall from grace in 1726 when he was the subject of a lettre de cachet. He spent 18 months in the Bastille,[3] was released in 1728, and retired to his estates in Champagne, where he entered into a long correspondence with Voltaire.

Later life and legacy edit

Pâris-Duverney became involved in military affairs again during the War of the Polish Succession. He was Administrator-General of Provisions from 1736 to 1758. This post and his extensive network of contacts enabled him to exercise extensive influence over government policy. His record in managing the public debt in 1721 and monetary policy from 1724 to 1726 was called into question by Nicolas Dutot in his work 'les Réflexions politiques sur les finances et le commerce' , and he defended himself by dictating, to his former cashier, François Deschamps, a two-volume work entitled 'l' Examen du livre intitulé réflexions politiques sur les finances et le commerce' which he had published at The Hague in 1740.[4]

His legacy includes the creation of the École militaire,[5] of which he was the first Intendant. From 1760 he protected and financed Pierre Beaumarchais, whom he introduced to the business world in exchange for favours at Court and for commercial and financial missions. He died at the age of eighty four, and as his only daughter Louise Michelle, wife of Louis Marquet, had already died in 1752, he left four grandchildren. He was buried in the chapel of the École militaire. He chose as his sole heir his great-grandnephew Alexandre de Falcoz, Comte de La Blâche, although Beaumarchais contested the will (see the Goëzman Affair).[6]

His nephew Jean-Baptiste Pâris de Meyzieu contributed one article to the Encyclopédie by Diderot and D'Alembert.

In popular culture edit

Marc Duret portrayed Duverney in Outlander season 2.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Gilbert Faccarello (11 September 2002). Studies in the History of French Political Economy: From Bodin to Walras. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-134-85768-5.

- ^ Voltaire (1824). Oeuvres complètes. P. Dupont. p. 311.

- ^ Steven L. Kaplan (1982). The Famine Plot Persuasion in Eighteenth-century France. American Philosophical Society. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-0-87169-723-3.

- ^ Koen Stapelbroek (2008). Love, Self-deceit, and Money: Commerce and Morality in the Early Neapolitan Enlightenment. University of Toronto Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-8020-9288-5.

- ^ Henault (1842). Abrégé chronologique de l'histoire de France depuis Clovis jusqu'a la mort de Louis XIV. E. Proux. p. 440.

- ^ Sarah Maza (11 May 1995). Private Lives and Public Affairs: The Causes Célèbres of Prerevolutionary France. University of California Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-520-20163-7.

Sources edit

- G. Casanova de Seingalt, Mémoires, Paris, Garnier frères, 1880, t. III, p. 355 – 356.

- Voltaire, History of the Parlement of Paris, Chapter LXI.

Bibliography edit

- Title unknown, L'Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, 1908. 1er semestre (vol. 57 / n°1171-1188) p. 837

- Title unknown, L'Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, 1923 (vol. 86 / n°1572–1592)

- Jules Michelet, Histoire de France, Paris, Lacroix, 1877, vol XVIII.

- Beaumarchais, Le Tartare à la Légion, édition établie et annotée par Marc Cheynet de Beaupré, Bordeaux, Castor Astral, 1998. Cet ouvrage retrace les liens noués entre Beaumarchais et Pâris-Duverney, ainsi que le procès intenté à Beaumarchais par le comte de la Blache au sujet de la succession de Duverney. Il contient en outre une généalogie fiable de la descendance des quatre frères Pâris.

- Marc Cheynet de Beaupré, Joseph Paris Duverney, financier d'État (1684-1770) - Ascension et pouvoir au Siècle des Lumières, thèse de doctorat en histoire, Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 2010, 1640 pp.