Summary

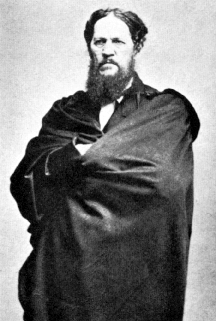

Josiah Harlan, Prince of Ghor (June 12, 1799 – October 1871) [1] was an American adventurer who travelled to Afghanistan and Punjab with the intention of making himself a king. During his travels, he became involved in local politics and factional military actions. He was awarded the title Prince of Ghor in exchange for military aid. Rudyard Kipling's short story The Man Who Would Be King is believed to have been partly based on Harlan.[2]

Josiah Harlan | |

|---|---|

Josiah Harlan in his Afghan robes | |

| Born | June 12, 1799 Newlin Township, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | October 1871 (aged 72) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | American adventurer, best known for traveling to Afghanistan and Punjab with the intention of making himself a king |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Baker |

| Children | Sarah Victoria Harlan |

| Relatives | Richard Harlan (brother) Scott Reiniger (great-great-great-grandson) |

Harlan's childhood edit

Harlan was born in Newlin Township, in Chester County, Pennsylvania.[3] Harlan and his nine siblings—including paleontologist Richard Harlan—were raised in a strict and pious home by Quakers. His father was a merchant broker in Philadelphia.

After losing his mother at the age of 13, Harlan took up reading. It was recorded that at the age of 15, he was reading medical books, such as the biographies of Plutarch. He also allegedly held interest in advanced religious texts.[4] Harlan had a knack for languages, as he was able to speak French fluently and could read in both Greek and Latin.[4] Furthermore, he enjoyed studying Greek and Roman ancient history, with Alexander the Great bearing a particular point of interest for him.[5]

Early travels edit

In 1820, Harlan embarked on his first travels after joining the Freemasons.[6] His father secured him a job as a supercargo on a merchant ship bound for Asia, sailing from Calcutta, India to Guangzhou, China and back.[7] After his return, he fell in love with Elizabeth Swaim, for whom he wrote several verses of poetry.[8] Soon after, they got engaged and planned to marry after he returned from the voyage to India and China. However, after his fiancée married someone else,[9] Harlan vowed to never return to America and used the word solitude several times in his writings.[9] He became aloof, developed a romantic loner persona, and became a man of action who lived only for glory.[10]

In July 1824, he enlisted as a military surgeon with the East India Company, despite his lack of medical training.[11] The company was about to enter the war in Burma and needed qualified surgeons. Relying on self-study and some practice while at sea, Harlan presented himself to the medical board for examination and was hired as a surgeon in the Calcutta general hospital.[11] In the first month of 1825, he served with the army in Burma.[12] Harlan admired the impressive capacity of the East India Company's sepoys, who "consumed nothing but parched grain, a leguminous seed resembling the pea", and yet kept going. Owing to heavy losses due to disease and war, Harlan sometimes fought with the Bengal Artillery, acquiring military knowledge that would be used in future exploits.[12] Harlan was at the Battle of Prome in 1825, where Anglo-Indian forces stormed the city of Prome (modern Pyay) and engaged in fierce hand-to-hand fighting with the Burmese. The Treaty of Yandabo in 1826 ended hostilities.[12]

Once recuperated, Harlan was posted to Karnal, north of Delhi. There, he read the 1815 book: An Account of the Kingdom of Caubul, and its dependencies in Persia, Tartary and India, comprising a View of the Afghan Nation and history of the Dooraunee Monarchy. This book was written by Mountstuart Elphinstone, who was then a civil servant with the East India Company, and had visited Afghanistan in 1809. While visiting Afghanistan, he met the country's king Shuja Durrani, a monarch who wore the Koh-i-Noor ("Mountain of Light") diamond on his left arm and was later deposed by his half-brother Mahmud Durrani during Elphinstone's visit.[13]

To many Westerners at that time, Afghanistan seemed remote and mysterious. Elphinstone's book described a nation that no Westerner had ever before visited, which quickly became a bestseller.[13] Harlan dreamed of a medieval Afghanistan, where tribal chiefs battled for supremacy.[14]

Harlan was a martinet who would not tolerate any insubordination from those serving under him. But he himself had difficulty taking orders and was openly insubordinate towards his superiors.[15] Harlan began to learn Hindi and Persian.[14] In the summer of 1826, he quit his service with the East India Company. As a civilian, he was granted a permit to stay in India by the Governor-General Lord Amherst.

At the time, India was a proprietary colony granted by The Crown to the East India Company, which had become the world's most powerful corporation, with monopolies on trade with India and China. By the early 19th century, the company ruled 90 million Indians, controlled 70 million acres (243,000 square kilometers) of land under its own flag, and issued its own currency. It maintained its own civil service and its own army of 200,000 men, led by officers trained at its officer school, which gave the Company a larger army than those of most European states.[16] The East India Company was not owned by the Crown, but many of its shareholders were MPs and aristocrats, giving it a powerful lobby in Parliament.[17] It was so powerful that several British Army regiments were sent out to serve alongside the Company's army. It was known simply as "the Company" in India, as it dominated both the political and economic life of India.[11]

Harlan disliked the Company as he claimed the Company showed no interest in the welfare of the Indians as it maximized profits for its shareholders and reduced the maharajahs and nawabs to mere ceremonial rulers without power. Harlan was proud that his own country was a republic, but he had a romantic, sentimental love of the pomp and ceremony of monarchy. He wanted to go to the Punjab and Afghanistan in part to see where monarchs had real power and were not controlled by foreign powers.[14]

Entering Afghanistan edit

After a stay in Shimla, Harlan came to Ludhiana, a border outpost of the British East India Company on the river Sutlej, which formed the border between the Sikh Empire and British India at the time. Harlan had decided to enter the service of Ranjit Singh, the Maharaja of Punjab.[18] Ranjit Singh was willing to hire Westerners who could be useful to him, but generally did not allow them to enter Punjab. He knew that the East India Company possessed much of the Indian subcontinent, and as far he was concerned, the less known of Punjab the better. So, Punjab became a rather mysterious region for Westerners.[19] The East India Company's agent in Ludhiana, Captain Claude Martin Wade, described Harlan as an enigmatic character who dressed well, knew much about the flora of India and the classics, and wanted to become a mercenary for Ranjit Singh. This made him the first classicist/botanist/soldier of fortune that Wade had ever met.[20] Harlan planned to study the flora of the Punjab, which was unknown in the West, and publish a book about the botany of Punjab with a special emphasis on flowers.[18]

While awaiting an answer to his request to enter Punjab, Harlan heard that the deposed King of Afghanistan lived in exile in Ludhiana. According to rumor, he was fabulously wealthy, and Harlan decided to enlist in his service, sending him a letter offering "a general proposition affecting the royal prospects of restoration".[21] At Shah Shujah Durrani's palace, Harlan discovered a court of grotesquely deformed men. Shuja had a habit of removing the ears, noses, tongues, and genitalia of his courtiers and slaves when they displeased him, and they all offended him at some point. Harlan commented Shuja's court was an "earless assemblage of mutes and eunuchs in the ex-king's service".[22] Harlan spoke no Pashto and Shuja no English, so they conversed in a mixture of Hindi and Persian.[22] Harlan praised "the grace and dignity of His Highness's demeanor", observing the sense of power that Shuja projected, but also that "years of disappointment had created in the countenance of the ex-King an appearance of melancholy and resignation".[23] When Shuja went out for a picnic with his wives, a gust of wind blew down his tent,[24] and Shuja became enraged. Much to Harlan's horror, Shuja had his chief slave, an African named Khwajah Mika who had arrived in India via the slave markets of Zanzibar, castrated on the spot.[25]

Shuja agreed to hire Harlan, and Harlan had a tailor in Ludhiana sew an American flag, which he used to imply that he was working for the U.S. government, as he went about recruiting mercenaries to restore Shuja.[26] By the fall of 1827, Harlan had recruited about 100 mercenaries, a mixture of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs interested in loot and plunder.[27]

Writing about Afghanistan's unstable politics, its frequently overthrown rulers, and the penchant for sons to conspire against their fathers, and brothers against brothers, Harlan noted: "The prize was literally handed about like a shuttlecock. The king who in the battle may have dispatched a favorite son in the command of his army would probably before night find himself flying from his own troops."[28] Afghanistan was dominated by a feud between two families, the Durrani and the Barakzai, and furthermore, the men of the Durrani and Barakzai families were just as much inclined to feud with other family members as they were with the rival families.[29] Shuja, who belonged to the Durrani family, had together with his brother Mahmud overthrown and blinded their brother Zaman. Shuja then deposed Mahmud and was overthrown by Mahmud, who in his turn was overthrown by the Barakzai brothers after he had their father Fateh Khan publicly chopped to pieces. In turn the Barazkais were now feuding among themselves.[29] 72 Barakzai half-brothers now ruled Afghanistan. Muslim traditions of polygamy allowed a man to have four wives at once, and an unlimited number of concubines, so their father had a surplus of sons. Given this history, and the fact that Afghan tribal chiefs tended to be loyal only to those who paid them the most, Harlan believed that despite the small size of his force that he could topple the Emir, Dost Mohammad Khan, who was the most able and intelligent of the fractious Barakzai brothers.[28]

With financial support from Shuja Shah Durrani, Harlan travelled along the Indus and into Afghanistan, first to Peshawar then to Kabul. During his journey, Harlan discovered in Ahmedpur two deserters from the East India Company's army, James Lewis, better known by his pseudonym Charles Masson and Richard Porter aka "John Brown", who tried to persuade him that they were Americans, but Harlan couldn't help but notice their English accents. Harlan correctly guessed that the only reason why two Englishmen out in the wildness would try to pass themselves off as Americans was that they were deserters.[30] The two deserters joined Harlan's army and maintained the pretense of being two gentlemen from Kentucky who had decided to explore the Hindu Kush.[31] As he entered Afghanistan, Harlan first met the warlike Pashtun tribes and learned about their strict code of Pashtunwali ("the way of the Pashtuns") under which any insult, real or perceived, had to be avenged with swift and blinding violence while at the same time, a man had to be courteous and honorable to all, including his enemies.[32] As Harlan's army was close to mutiny, he decided he would enter Afghanistan disguised as a Muslim dervish (holy man) returning from a pilgrimage to Mecca.[33] Much to Harlan's fury, Masson deserted his army and inspired several others to follow his example.[34] Harlan knew only a few phrases in Arabic, but it he convinced a Pashtun chief that he was a dervish returning from Mecca.[35] Shuja followed Harlan's force with his own troop of mercenaries, seizing Peshawar, the summer capital of Afghanistan. He behaved with such arrogance towards the Pashtun chiefs who had come to swear loyalty to him, expecting lavish financial rewards, that they went back to the Bazakzai brothers, who did not use court etiquette to humiliate them as Shuja had done.[36]

Harlan met the man who he had come to depose in Kabul, Dost Mohammad Khan, at Bala Hisar Fort.[37] The custom of Pashtunwali ensured that Dost Mohammad would choose to treat Harlan as an honored guest. By this time, Harlan had become fluent in Persian, the lingua franca of the Muslim world, and it was in that language that he and Dost Mohammad talked.[37] Even through Harlan had come to Afghanistan to overthrow Dost Mohammad, upon meeting him, he discovered he rather admired him.[38] Unlike the rulers from the House of Durrani, who used the title of Shah (Persian for king), the monarchs of the House of Bazakzai used the less grand title of Emir (Arabic for prince). Pashto had such low status in the Muslim world that both the Durranis and Barakzais used Arabic and Persian titles to improve their prestige.[39] Harlan had arrived assuming the West was superior to the East, but meeting Dost Mohammad challenged his thinking, as he found Easterners could be just as intelligent as Westerners.[40] When Dost Mohammad asked Harlan to explain the American system of government to him, Harlan spoke about the tripartite separation of powers between the President, Congress, and the Supreme Court. The Emir remarked the American system did not sound much different from the Afghan system, where there was a tripartite separation of powers between the Emir, the tribal chiefs, and the Ulama (Islamic clergy who also served as judges).[40] Harlan noted that although a Muslim, Dost Mohammad drank heavily and had brought prostitutes to his court; Harlan described them as "promiscuous actors in the wild, voluptuous, licentious scene of shameless bacchanals".[41]

Harlan explored Kabul, the "city of ten thousand gardens", observing that there were so many gardens in the city full of sweet-smelling flowers and fruits they almost covered the smell of human and animal excrement dumped in the streets.[42] Harlan wrote Kabul was a "jewel encircled with emerald with flowers and blossoms whose odors perfume the air with a fragrance elsewhere unknown".[43] Harlan called Kabul a "sweet assemblage of floral beauty" full of "ornamental trees, apple orchards, patches of peach and plum trees, vast numbers of mulberry of various species, black, white and purple, with the sycamore, the tall poplar, the sweet scented and the red and white willows, the weeping willow, green meadows, running streams and hedges of roses, red, white, yellow and variegated".[44]

Harlan observed that Kabul had a lively red-light district full of "professional courtesans [sic] or female singers and dancers, libidinous creatures whose lives are passed in the immodest and secret intrigues of licentiousness". Macintyre wrote that Harlan's disapproving tone suggested considerable experience of the red-light district of Kabul.[45]

A difficult moment for Harlan emerged when Hajji Khan, a mercenary working for Dost Mohammad, approached him with a plan to assassinate the Emir and restore Shuja to the throne. Harlan was uncertain if Khan was working as an agent provocateur sent by Dost Mohammad to test his loyalty (meaning he would be executed if he agreed to the plot) or was sincere (meaning he would kill Harlan if he refused to join the plot).[46] Harlan suggested that the two should go off and invade the Sindh together; when Khan persisted, Harlan said he could never violate the rules of Pashtunwali by conspiring to murder his host, at which point Khan told him that the Emir extended him his thanks for his willingness to observe Pashtunwali.[46] Shortly afterwards, a cholera epidemic hit Kabul, killing off much of the population, owing to the feces-ridden water of Kabul.[47] Harlan was infected with cholera and wandered into a mosque one night which was a morgue full of the bodies of cholera victims.[48] As Harlan left the mosque, he tripped over bodies piled up in the streets.[49] At that point, an anonymous man told Harlan that the only cure for cholera was to drink alcohol, saying if one consumed enough alcohol that cholera could be survived. Harlan was raised a teetotaler, but to survive cholera he broke with his Quaker values by drinking as much as possible of the wine and whisky smuggled into Afghanistan from India.[49] An attack of cholera typically lasts 48 hours, during which the body excretes fluids, causing intense dehydration leading to death, which can be countered by consuming enough fluids such as alcohol which are not infected. After surviving cholera, Harlan later stated he looked death in the eye, and was never again afraid of death.[49]

In Peshawar, Harlan had met a Nawab Jubbar Khan, who was a brother of Dost Mohammad Khan. Jubbar Khan was important as a possible rival of Dost Mohammad, and thus a possible ally to Shuja Shah. During this time, Harlan met an Afghan maulvi (Islamic scholar) who also worked as an alchemist and doctor, whose name no-one knew and whom Harlan called "the Moolvie".[50] Harlan discovered much to his amazement that the maulvi "was an enthusiastic Rosicrucian" who was seeking the Philosopher's stone, and who kept Jubbar Khan happy with the supposed medical secrets that his occult knowledge gave him.[51] Harlan soon discovered that the maulvi was a fraud, who once insisted that his alchemy could only work if he was provided with a large number of unusually large fish from a local river; when after much difficulty the requisite number of big fish were caught, the maulvi only then "remembered" that they all had to be of the same sex for his alchemy to work, at which point the fishing season had passed.[52] Harlan often argued with the maulvi, telling him about that modern chemist in the West had firmly established it was not possible to turn lead into gold, much less turn fish into silver, as he insisted that he could.[53] While staying with Jabbar Khan, Harlan evaluated the situation and realized that Dost Muhammad's position was too strong, and that influence from outside Afghanistan was needed. He decided to seek his luck in Punjab. Upon his return to the Punjab, Wade admitted to Harlan that Shuja would never be restored to the throne of Afghanistan, saying: "There is now no possible chance for Shuja's restoration, unless an ostensible demonstration of Russian diplomacy should transpire in Kabul."[54] Wade's reference to "Russian diplomacy" in Kabul was Harlan's initiation into the struggle for influence in Central Asia between Russia and Britain known to the British as the Great Game and to the Russians as the "Tournament of Shadows".[55]

Maharaja Ranjit Singh edit

Harlan came to Lahore, the capital of Punjab, in 1829. He sought out the French general Jean-François Allard, who introduced him to the Maharaja.[56] Allard had been awarded the Légion d'honneur by Napoleon and was the Western officer that Ranjit Singh trusted the most.[57]

Ranjit Singh, the "Lion of Lahore" had conquered much of what is today north-western India and Pakistan and was considered to be one of the most powerful rulers in the Indian subcontinent, which is why Harlan sought to work in his service.[58] As a rule, Ranjit Singh was against taking anybody British into his service as he held deep suspicions of the Company and mistrusted the loyalties of the few Britons in his service.[59] His European such as French and Italian officers were part of the Dal Khalsa army, which was one of the most formidable military machines in Asia. Their contribution to the empire was well rewarded. [56] As a result, Ranjit Singh paid his Western officers well and Harlan noted that Allard lived in a grand mansion, which he called "a miniature Versailles in the midst of an Oriental bazaar".[56]

Allard was lonely in the Punjab, unable to relate to the Indians, and was known to welcome any Westerner. He received Harlan as a guest, warning him "It is a very difficult to get an appointment here, but still more to get one's dismissal, when once in office".[60] Allard wrote a poem calling himself a happy "slave" of Ranjit Singh because he wanted to visit his homeland, France, with his Kashmiri wife, and Ranjit Singh had initially refused him permission to leave, thus requiring an obsequious poem to being allowed a visit home.[61] Allard introduced Harlan to Ranjit Singh, dressed all in white with a matching white turban, who proudly wore the Koh-i-Noor diamond (which he had taken from Shuja) and radiated an aura of power.[62] As Harlan knew no Punjabi, he spoke to Singh in Hindi.[63][64]

Harlan was offered a military position but declined, looking for something more lucrative.[62] This he eventually found: after lingering at the court for some time he was offered the position of Governor of Gujrat District, a position he accepted. Ranjit Singh told Harlan, "I will make you Governor of Gujrat and give you 3,000 rupees a month. If you behave well, I will increase your salary. If not, I will cut off your nose".[65] Before giving him this position, however, the Maharaja decided to test Harlan. In December 1829, he was instated as Governor of Nurpur and Jasrota, described by Harlan himself as "two districts then newly subjugated by the King in Lahore, located on the skirt of the Himalah mountains".[66] These districts had been seized by the maharajah of the Punjab in 1816 and were fairly wealthy at the time Harlan arrived. Little, if anything, is known of Harlan's tenure there, but he must have fared well. One visitor noted that given Ranjit Singh's habit of cutting off the noses of those who failed him that "The fact of his nose being entire, proved that he has done well".[66] In May 1832 he was transferred to Gujrat.[67] In Gujrat, Harlan was visited soon after his instatement by Henry Lawrence who later described him as "a man of considerable ability, great courage and enterprise, and judging by appearance, well cut out for partisan work".[68] Harlan later wrote "I was both civil and military governor" with unlimited powers to do whatever he pleased as long as taxes were collected, and order maintained.[68] While serving the durbar, Harlan often encountered the Akalis, militant and heavily armed Sikh fundamentalists, who Harlan noted were seen "riding about with sword drawn in each hand, two more in the belt, a matchlock at the back and then a pair of quoits fastened around the turban-an arm peculiar to this race of people, it is a steel ring, ranging from six to nine inches in diameter, and about an inch in breath, very thin, and at the edges very sharp; they are said to throw it with such accuracy and force as to be able to lop off a limb at sixty or eighty yards".[69] The weapon that Harlan described as a "quoit" is better known as the chakram.

One of Harlan's visitors was the Reverend Joseph Wolff, a Bavarian Jew who had converted successively to Catholicism, Lutheranism and finally Anglicanism, and was now traveling all over Asia as a missionary.[70] After being ordained a minister at Cambridge, Reverend Wolff had set off to Asia to find the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel and covert all the peoples of Asia to the Church of England.[71] Wolff had arrived at Gujrat and asked to see the governor, expecting him to be a Sikh sardar (nobleman) and was surprised that the governor was whistling Yankee Doodle Dandy and he introduced himself as: "I am a free citizen of the United States, from the state of Pennsylvania, city of Philadelphia. I am the son of a Quaker. My name is Josiah Harlan".[72] Wolff said Harlan wore a very expensive Western suit and liked to smoke a hookah.[73] Wolff was one of the few people with whom Harlan spoke of his love for Swaim, as Wolff wrote in his journal: "He fell in love with a young lady who promised to marry him. He sailed to Calcutta; but hearing that his betrothed lady had married somebody else, he determined never again to return to America".[9] Harlan also confessed to Wolff his dream of ruling Afghanistan, and Wolff noted: "He speaks and write Persian with great fluency; he is clever and enterprising. Dr. Harlan is a high Tory in principles, and honors kingly dignity; though on the other hand he speaks with enthusiasm of Washington, Adams and Jefferson, who wrote the Declaration of Independence".[74]

While European governors were rare, Harlan was certainly not the only one. His colleague Paolo Avitabile was made governor of Wazirabad, and Jean-Baptiste Ventura was made governor of Dera Ghazi Khan in 1831. Avitabile once had a group portrait done of all the Westerners in Ranjit Singh's service, which depicted him, Allard, Ventura, Claude Auguste Court, and Harlan all standing together.[69] Unlike Ventura and even more so Avitabile, who believed that violence was the only language Indians were capable of understanding and who terrorized their provinces, Harlan attempted to crack down on corruption and avoided brutality, which caused his relations with Ventura and Avitabile to decline.[75] Harlan was also in turn followed in his position in Gujrat by an Englishman named Holmes, who failed Singh, and lost more than his nose, being publicly beheaded as an example of the fate of those who failed the Maharajah. During his time as governor of Gujrat, Harlan's principal friend was the maulvi, as the alchemist from Afghanistan unexpectedly showed up at his palace one day. The maulvi taught Harlan about "the traditional lore of Arabia" while the alchemist wanted Harlan to sponsor him to join a Masonic lodge as Harlan noted "My refusal to explain the craft of Freemasonry added to his conviction that in the secrecy of that forbidden region of science lay the Philosopher's Stone".[76]

Joining Harlan in Gujrat was the American adventurer Alexander Gardner who had come down from Central Asia, looking for employment with Singh and arrived at Harlan's palace to seek the company of a fellow American.[77] Gardner, who claimed to have been born in a fur-trading post on Lake Superior in what is now Wisconsin to a Scots father and an Anglo-Spanish mother in 1785, was always very proud of his Scottish heritage.[76] Gardner wore a turban and Asian-style clothing in a tartan print, a colorful reminder of his Scots heritage, as Gardner was insistently Scottish-American in his identity during his various adventures as a mercenary in Central Asia, where he had fled after deserting from the Imperial Russian Army in 1819.[43] Gardner claimed that during his childhood on the shores of Lake Superior the Ojibwe Indians had taught him how to fight. Whether or not this was true, Gardner was a fighter, his body was covered with wounds, most notably a gaping hole in his throat that required him to wear a neck-brace to drink.[43] Gardner told Harlan that he and his followers "... did not slaughter except in self-defense" during his time in Central Asia.[76] While fighting against Dost Mohammad in the pay of the warlord Habibullah Khan, Gardner's wife and his infant daughter had been killed by the Emir's forces after being captured, causing him to head to the Punjab.[76] Gardner, who was known as "Gordana Khan" in Central Asia, recalled: "I remained a few days with Dr. Harlan and on meeting my countryman, I resumed the character of a foreigner, and resumed also the name of Gardner, which I abandoned for so long that it sounded strangely in my ears".[43]

In 1834, the Sikh general Hari Singh Nalwa finally captured the contested city of Peshawar for the Punjab, leading Dost Mohammad Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan, to send the Maharajah an insulting letter demanding the return of Peshawar or else face war, leading Ranjit Singh to reply with an equally insulting letter challenging Dost Mohammad to retake Peshawar if he dared.[78] In the spring of 1835, Dost Mohammad, anxious to regain Peshawar, declared jihad on the Punjab.[79] The traditional hatred between the Sikhs and Afghans meant there was no shortage of volunteers in Afghanistan to go kill Sikhs, and a huge number of tribesmen rallied to Dost Mohammad's banner.[79] Macintyre noted the Afghans had a "fanatical" hatred of the Sikhs, which to a certain extent compensated for the superior training and firepower of the Dal Khalsa.[80] As the Dal Khalsa faced off against the Afghans, the no-man's land between the two armies was soon littered with corpses as tribesmen from the Pashtun Ghazi tribe faced off in skirmishes against the Akali.[81] Gardner observed "the Sikhs sadly lost many lives at the merciless hands of the Ghazis, who, each with his little green Moslem flag, boldly pressed on, freely and fairly courting death and martyrdom". The Akali were equally enthusiastic in using their quoits to cut down Ghazis.[81]

Ranjit Singh, knowing that the feuding Barakzai brothers were as much inclined to fight among themselves as against their enemies and that Harlan knew the Barakzai brothers, ordered him up to the front to see if he could divide the Afghan leaders.[82] The Emir's half-brother Sultan Mohammad Khan had fallen in love with a dancing girl at the court, whom he was planning to take into his harem to make into another of his concubines, but Dost Mohammad who also desired her, had used his right as Emir to take her into his harem, causing much discord between the Barakzai brothers, which Harlan knew about.[82] Viewing the Afghan camp outside of Peshawar, Harlan reported seeing: "Fifty thousand belligerent candidates for martyrdom and immortality. Savages from the remotest recesses of the mountainous districts, many of them giants in form and strength, promiscuously armed with sword and shield, bow and arrows, matchlocks, rifles, spears and blunderbusses, concentrated themselves around the standard of religion, and were prepared to slay, plunder and destroy, for the sake of Allah and the Prophet, the unenlightened infidels of the Punjab". Dal Khalsa was a powerful army, but Ranjit Singh as usual preferred to achieve his goals via diplomacy rather than war if possible, and so sought to find a peaceful way to send the Afghans home.[82]

Under the flag of truce, Harlan went to the camp of Sultan Mohammad Khan, the half-brother of the Emir, to negotiate the right price for defecting, and he was motivated by his resentment of Dost Mohammad for taking away the dancing girl he desired to turn him against the Emir.[83] Already, many Sikhs and Afghans, anxious to spill each other's blood, had engaged in skirmishes and the ground between the two armies that Harlan traveled through was littered with corpses.[81] Harlan offered Sultan Mohammad a generous bribe on the behalf of Ranjit Singh in exchange for going home with that part of the Afghan host under his command.[84] Dost Mohammad had heard that Harlan had arrived in his half-brother's camp. But he then received a letter from Sultan Mohammad Khan "stating the fact of Mr. Harlan's arrival, and that he had been put to death, while his elephants and plunder had been made booty".[81] The news was received with loud cheering in Dost Mohammad's camp, and it was announced that "now the brothers had become one and wiped away their enmities in Feringhi blood".[81] After agreeing to consider whether to accept Singh's bribe, Harlan and Sultan Mohammad Khan rode into Dost Mohammad's camp, where Harlan told the Emir to go home, telling him that despite his 50,000 men that "If the Prince of the Punjab chose to assemble the militia of his dominions, he could bring ten times that number into the field, but you will have regular troops to fight, and your sans-culottes militia will vanish like mist before the sun".[85] Dost Mohammad then made a veiled threat to kill Harlan, reminding Harlan that when "Secunder" (Alexander the Great) had fought in Afghanistan one of his envoys had been killed under the flag of truce. A servant brought in some doug (fermented milk) to drink, which Sultan Mohammad refused to drink, believing his half-brother was attempting to poison him.[86] When Dost Mohammad insisted that Sultan Mohammad drink some of the doug under the grounds it was rude to refuse his hospitality, his half-brother insisted that the Emir drink some of the doug first, which he refused under the grounds it's too hot of a day to drink a doug, leading to a lengthy argument between the two about who was drink the doug first.[87] Dost Mohammad finally drank some of the doug just to prove it was not poisoned.[87] Dost Mohammad had played a cunning trick on his half-brother as the reluctance of Sultan Mohammad to drink the doug first proved to the assembled tribal chiefs that he had been engaging in treachery, as Dost Mohammad had intended.[88] The meeting was first of several tense meetings as Harlan traveled back and forth between the Sikh camp and the two half-brothers before Sultan Mohammad was finally bribed into switching sides while Ranjit Singh had brought up his heavy artillery, which finally persuaded Dost Mohammad that discretion was the better part of valor, leading him to go home.[89] Harlan had played the role of a diplomat well, seeing off an Afghan invasion with minimal losses to the Dal Khalsa; but Ranjit Singh decided after the fact that it would have better to have given battle after all, and publicly criticized Harlan for preventing a battle that he believed he could have won, the beginning of a rift between the two.[90]

On August 19, 1835, Ranjit Singh had a stroke, which left him with slurred speech, and demanded that Harlan use his knowledge of Western medicine to cure him.[91] In the 19th century it was widely believed that running electrical jolts through the body had restorative effects, and following Harlan's advice, Ranjit Singh had the services of a British doctor, Dr. William McGregor, competent in the application of galvanism to his emaciated body should be placed at his disposal. Electrical machine was brought to Lahore to pump Ranjit Singh with electricity, an experience that did not restore his speech.[92] The final blow to his relations with Ranjit Singh occurred when Ranjit Singh was informed that Harlan was secretly employing his time in his fortress in the practice of alchemy and transmutation of metals, where Harlan had the maulvi living with him who was alleged to be able to turn base metals into precious gold ones (refusing to share the knowledge was tantamount to treason) and that Harlan was allegedly minting counterfeit coins (a crime for which the penalty was death).[93] In fear of his life, Harlan left Ranjit Singh's employ in early 1836.[94] An Indian historian Khushwant Singh called Harlan "an incredible windbag" who was somehow able to convince Ranjit Singh that he was a "doctor, scholar, statesman and soldier".[95]

Afghanistan edit

In 1836, after a falling-out with Ranjit Singh, Harlan defected over to the service of Dost Mohammad Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan and the archenemy of Singh.[96] Even though Harlan, while in the service of Singh and Shah Shujah, had fought against Dost Mohammad in the past, the Emir was sufficiently impressed with Harlan's ability to accept his former enemy into his service. In the treacherous world of Afghan politics, where today's enemy was likely to be tomorrow's friend, and today's friend to be tomorrow's enemy, Dost Mohammad had learned not to hold grudges.[97] Arriving in Kabul, Harlan ran into Charles Masson who had deserted his earlier expedition to Afghanistan, an act that Harlan had not forgiven him for. Harlan sent a letter to the East India Company telling them that Masson, the "American" explorer and amateur archaeologist of Central Asia, was actually the Englishman James Lewis, a deserter from the Company's army sentenced to death in absentia.[97] Captain Wade used this information to blackmail Masson into working as a spy for the Company, promising him a pardon if he agreed to work as a spy, and to have him extradited back to India to be executed if he refused his offer.[98] Masson was a most unwilling player in the "Great Game", not the least because he knew Dost Mohammad would have him executed if he found out he was working as a spy for the Company. Masson, suspecting that it was Harlan who had denounced him to the Company, started denouncing him to the Company as a "violent and unprincipled man".[98]

In March 1836, Lord Auckland, the Governor-General of India, received a letter in English purportedly from Dost Mohammad (who did not know English), whose flowery style and Americanisms strongly suggested that Harlan was the real author, asking him to sign an alliance and force Ranjit Singh to return Peshawar to Afghanistan.[99] Writing as Dost Mohammad, Harlan declared: "The field of my hopes, which had before been chilled by the cold blast of the wintry times, has by the happy tidings of your Lordship's arrival become the envy of the Garden of Paradise", going on to ask the British to ensure "the reckless and misguided Sikhs" to return Peshawar to the Afghans.[99] Lord Auckland replied: "My friend, you are aware that it is not the practice of the British government to interfere with the affairs of the independent states".[99]

Dost Mohammad wanted Harlan to train his tribal levy (Afghanistan had no army) to fight in the Western style of war.[100] The French had traditionally excelled at artillery, and as befitting an army supported by French officers of the Sikh Empire, the Dal Khalsa had excellent artillery, which had been repeatedly used to decimate the Afghan tribesmen in various battles. Singh had been pushing steadily into the "badlands" on the modern border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, but in 1837 he recalled the best of the Dal Khalsa for a parade to honor his son's wedding in Lahore, which Dost Mohammad took advantage of by attacking the Sikhs.[101] Under the banner of jihad, about 20,000 Afghan tribesmen swept down the Khyber Pass under the command of Dost Mohammad's son Wazir Akbar Khan to attack the Sikhs, accompanied by Harlan as his special military adviser. On April 30, 1837, the Afghans battled the Sikhs at the Battle of Jamrud.[101] At Jamrud, the Sikh artillery blasted holes in the Afghan ranks, with a single cannonball killing or wounding dozens of men, but when the Sikh infantry advanced through the gaps in the Afghan line, the Afghans, following Harlan's advice, used their numerically superior reserves to crush the Dal Khalsa in furious hand-to-hand fighting. The Afghans lost about 1,000 killed while the Sikhs lost about 2,000 dead, including General Hari Singh Nalwa, Ranjit Singh's favorite general.[101] Harlan wrote that Singh must had been besides himself with fury, imagining that "The proud King of Lahore quailed upon his threatened throne, as he exclaimed with terror and approaching despair, 'Harlan has avenged himself, this is all his work'".[102] Singh reacted by sending his best general, the French mercenary Jean-François Allard to avenge the death of his general, while the Afghans—unable to take the fortress of Peshawar—retreated back beyond the Khyber Pass, starting on May 9, 1837.[102] Feeling his hold on Peshawar was weak, Singh appointed the Neapolitan mercenary General Paolo Avitabile the new governor of Peshawar with orders to terrorize the city into submission, using methods that Harlan called barbaric.[103]

Harlan liked and admired Dost Mohammad, whom he called a hard-working, self-disciplined and efficient emir who always got up early every morning to pray towards Mecca and read the Koran before receiving tribal chiefs except on Thursday, which was the only day of the week that Dost Mohammad took a bath.[104] After discussing the affairs of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammad would have his breakfast at 11 am, to be followed by new meetings before retiring to his harem to enjoy his concubines, to be followed by a ride around Kabul in the afternoon to hear the complaints of his subjects.[105] After he turned thirty, Dost Mohammad ceased drinking and having orgies with prostitutes, becoming a more much pious Muslim than he had been when younger.[106] Harlan noted that Dost Mohammad had shirrun i huzzoor, the Pashtun quality of modesty and politeness, but that he was also an "exquisite dissembler" capable of "the most revolting cruelty", very greedy for gold, and extremely cynical, doubting every motive except for self-interest as a reason for a man's actions.[107] Harlan noted that Dost Mohammad was a hypocrite who denounced slavery as a great evil, but who owned slaves himself and did nothing to shut down the slave markets of Kabul, where Uzbek slavers were always bringing in Hazara slaves captured in their raids.[108] Harlan observed that Dost Mohammad was stern in his rule as once he was presented with a man and a woman who had been captured when a "nocturnal orgie" had been discovered; the others had escaped, but this couple had been too drunk. Harlan observed that Dost Mohammad "listened to the charges of licentiousness and immorality", and with a wave of his hand ordered the man's beard to be burned off while the woman was to be put into a bag and given 40 lashes with a whip. When Harlan asked why the woman had to be put into a bag before whipping her, the Emir replied, "To avoid the indecency of exposure".[109]

As part of the "Great Game" between Britain and Russia for influence in Central Asia, on September 20, 1837, Alexander Burnes, the Scotsman who had been appointed the East India Company's agent in Kabul, arrived, and immediately became Harlan's rival. Harlan wrote that Burnes was "remarkable only for his obstinacy and stupidity". Together with the pseudo-American Charles Masson, Burnes and Harlan were the only westerners in Kabul, and all three men hated one another.[110] In Afghanistan, the Emir was expected to reward loyal chiefs with gifts, which given the poverty of Afghanistan meant the Emirs expected equally lavish gifts from foreign ambassadors, and Harlan recorded that Dost Mohammad was greatly offended when the only gifts that Burnes brought with him were two pistols and a spyglass.[111] Joining the three quarreling Westerners in Kabul in December 1837 was a Polish orientalist in Russian service, Count Jan Prosper Witkiewicz, who had arrived in Kabul as the representative of the emperor Nicholas I of Russia.[112] With Witkiewicz's arrival, the "Great Game" entered an intense new phase, and Burnes was visibly disconcerted by Witkiewicz's presence in Kabul, believing Afghanistan was falling into the Russian sphere of influence. Burnes had Christmas dinner with Dost Mohammad, Harlan and Witkiewicz, writing about the latter: "He was a gentlemanly and agreeable man, of about thirty years of age, spoke French, Turkish and Persian fluently, and wore the uniform of an officer of the Cossacks".[112]

Prince of Ghor edit

In 1838, Harlan set off on a punitive expedition against the Uzbek slave trader and warlord Mohammad Murad Beg.[113] He had multiple reasons for doing this: he wanted to help Dost Mohammad assert his authority outside of Kabul; he had a deep-seated opposition to slavery; and he wanted to demonstrate that a modern army could successfully cross the Hindu Kush.[113] Taking a force of approximately 1,400 cavalry, 1,100 infantry, 1,500 support personnel and camp followers, 2,000 horses, and 400 camels, Harlan thought of himself as a modern-day Alexander the Great. In emulation of Alexander the Great, Harlan also took along with him a war elephant.[114] He was accompanied by a younger son and a secretary of Dost Mohammad. Dost Mohammad sought to collect tribute from the Hazara, who were willing if the Afghans also ended Murad Beg's raids. Before leaving Kabul to hunt down Murad Beg, Dost Mohammad, knowing of Harlan's fascination with ancient Greece, gave him a gift of a piece of jewelry found at Bagram, the site of the ancient Greek city of Alexandria ad Caucasum, depicting the goddess Athena, which greatly moved him.[115] Just like his hero Alexander the Great, Harlan discovered that his war elephant could not handle the extreme cold of the Hindu Kush mountains, and Harlan was forced to send the elephant back to Kabul.[116] High up in the Hindu Kush at the pass of Khazar, a good 12,500 feet above sea level, Harland had the Stars-and-Stripes raised on the highest peak with troops firing a twenty-six-gun-salute as Harlan wrote: "the star spangled banner gracefully waved amid the icy peaks and soilless rugged rocks of the region, seeming sacred to the solitude of an undisturbed eternity".[117] Harlan then led his army down "past glaciers and silent dells, and frowning rocks blackened by age", battling rain and snow as "these phenomena alternately and capriciously coquetted with our ever changing climate".[118]

After an arduous journey (which included an American flag-raising ceremony at the top of the Indian Caucasus), Harlan reinforced his army with local Hazaras, most of whom lived in fear of the slave traders. The Hazaras are believed to be the descendants of the Mongols who conquered Afghanistan in the 13th century, which made them different both culturally and to a certain extent linguistically from the rest of the Afghan peoples. (The Hazaras speak a distinctive sub-dialect of Dari, which itself is a dialect of Persian.) Harlan noted the Hazaras did not look like other Afghans.[119] Because the Hazaras are ethnically distinct and are Shia Muslims, the Sunni Muslim Uzbeks and Tajiks liked to raid their lands for slaves. Harlan noted that because of the fear of Uzbek slavers, the houses of the Hazaras were "half sunk into slopes of hills" under "a bastion constructed of sun-dried mud, where people of the village can resort in case of danger from the sudden forays of the Tartar robbers."[120] Harlan further noted the brutality of the Uzbek slavers who sewed their victims together as they marched them off to the slave markets, observing:

To oblige the prisoner to keep up, a strand of course horsehair is passed by the means of a long-crooked needle, under and around the collar bone, a few inches from its junction at the sternum; with the hair a loop is formed to which they attach a rope that may be fastened to the saddle. The captive is constrained to keep near the retreating horseman, and his hands tied behind his person, is altogether helpless.[121]

Harlan's first major military engagement was a short siege at the citadel of Saighan, Afghanistan controlled by the Tajik slave-trader Mohammad Ali Beg. Harlan's artillery made short work of the fortress.[122] As a result of this performance, local powers clamored to become Harlan's friends as various Hazara chiefs asked to see Harlan, the man who had brought down the walls of the mighty fortress of Saighan, and who promised to end the raids of the slavers.[123]

One of the most powerful and ambitious local rulers was Mohammad Reffee Beg Hazara, a prince of Ghor, an area in the central and western part of what is now the country of Afghanistan. He and his retinue feasted for ten days with Harlan's force, during which time they observed the remarkable discipline and organization of the modern army. They invited the American back to Reffee's mountain stronghold. Harlan was amazed by the working feudal system. He admired the Hazaras, both because of the absence of slavery in their culture and by the gender equality he observed (unusual in that region at the time).[124] Harlan observed that the Harzara women did not wear veils, worked out in the fields with their husbands, loved to hunt deer with their greyhound dogs while riding horses at full gallop and firing arrows aside their mounts, and even went to war with their menfolk.[124] Writing about relations between the sexes among the Hazaras, Harlan noted:

"The men display remarkable deference for the opinions of their wives...The men address their wives with the respectful and significant title of Aga, which means mistress. They associate with them as equal companions, consult with them on all occasions, and in weighty matters, when they are not present, defer a conclusion until the opinions of their women can be heard".

A strong advocate of sexual equality, Harlan was greatly impressed with the Hazara women who were the equals of the Hazara men, and whom he also praised as most beautiful.[124] Macintyre noted that Harlan's purple prose tended to be at its most purplest when he was in love, and in his descriptions of the Hazarjat, Harlan's flowery style was at its most florid, leading Macintyre to speculate Harlan found love with a Hazara girl.[125] At the end of Harlan's visit, he and Reffee came to an agreement. Harlan and his heirs would be the Prince of Ghor in perpetuity, with Reffee as his vizier. In return, Harlan would raise and train an army with the ultimate goal of solidifying and expanding Ghor's autonomy. At another fortress, that of Derra i Esoff, ruled by an Uzbek slaver Soofey Beg, who had recently enslaved 300 Hazara families, Harlan began a siege and soon his artillery had smashed holes in the wall of the fortress.[126] Harlan sent his Hazara tribesmen into the breach, writing:

"In the storming of Derra i Esoff these men were amongst the first to mount the breach, along with their regimental colours. Their firmness and bravery, and, more especially their fidelity to their officers, were creditably displayed on many occasions".[127]

After taking the fortress, Harlan found about 400 Hazara slaves, whom he promptly had "released from a loathsome confinement in the dry wells and dungeons of the castle and sent home to their friends".[127] Harlan tracked Murad Beg down to his fortress in Kunduz. Beg dragged out the only cannon at his fort, an old Persian gun left over from the days of Nadir Shah to try to intimidate Harlan.[128] As an amateur horticulturist, Harlan was offended that the Uzbeks were much more interested in raiding for slaves than in growing flowers, noting "Little attention is bestowed upon the elegant in horticulture. Their flowers are, consequently, few and not of a pleasing variety".[128] As soon as Harlan reached Kunduz, Murad Beg sent out emissaries to resolve a diplomatic solution as Harlan noted: "The Uzbecks [Uzbeks] have a great horror of bloodshed, and think that prudence is the better part of valor".[128] Harlan further noted that Uzbek armies always fought the same way: "a few individual sallies of vaunting cavaliers are made in advance, the parties uttering unearthly yells of defiance, and assuming threatening attitudes. A parley ensures, an interview between the leaders follow, and the affair terminates with the harmless festivals of a tournament."[129] As Harlan surrounded Kunduz, Murad Beg, who was terrified of giving battle, chose to make a treaty with Harlan to recognize Dost Mohammad as the Emir of Afghanistan and to stop slave raiding in exchange for being allowed Kunduz.[129] Harlan described Murad Beg as:

"A great bear of a man with harsh Tartar features. His eyes were small and hard as bullets, while his broad forehead was creased in a perpetual frown. He wore no beard and was no more richly dressed than his followers, except that his long knife was richly chased, as was the smaller dagger with which he toyed with while talking".[130]

However, when Harlan returned to Kabul the British forces with William Hay Macnaghten arrived to occupy the city in an early stage of the First Anglo-Afghan War. The British had restored Shuja, and Harlan heard a proclamation read by Shuja's herald from the Bala Hisar fortress: "Everyone is commanded not to ascend the heights of the vicinity of the Royal harem under the pain of being disemboweled alive. May the king live forever!".[131] Harlan commented that Shuja's "harsh barbarity" had not changed, and he was going to be just as hated by his people now that he was restored as he was when was overthrown the first time back in 1809.[132] Harlan quickly became a persona non-grata, and after some further travel returned to the United States.[133]

Homeward bound edit

After leaving Afghanistan, Harlan spent some time in Imperial Russia. A woman he knew in England, sent letters to Russian nobility in which she claimed that Harlan was an experienced administrator who could help the Russian peasantry better itself. Though he was well liked by Russia's society women, Harlan made no important government contacts and soon decided to go back to America.

Once he returned to America, Harlan was feted as a national hero. He skillfully played the press, telling them not to dwell on his royal title, as he "looks upon kingdoms and principalities as of frivolous import, when set in opposition to the honorable and estimable title of American citizen".[134] His glory quickly faded after the publication in Philadelphia of A Memoir of India and Afghanistan − With observations upon the present critical state and future prospects of those Countries. Harlan had been working on a longer book called The British Empire in India, but the almost total annihilation of the British force retreating from Kabul in the Hindu Kush in January 1842 attracted much media attention in the United States, so Harlan tried to cash in with his hastily written and published A Memoir of India and Afghanistan.[135] In his book Harlan attacked enemies he made in India, both European and Indian. Most alarmingly, he wrote about the ease with which Russia could, if it so chose, attack and seriously harm the British Empire. Harlan was denounced in Britain, although, as one historian has observed, his book was

"officially discredited, but secretly read, under the table, by historians and British strategists".[136]

The American press did not pan him, but the controversy ensured that he would never publish another book. The writer Herman Melville appears to have read A Memoir of India and Afghanistan, as the references to the First Anglo-Afghan War in Moby Dick seem to be based on Harlan's book.[137]

With his funds dwindling, Harlan took on new tasks. He began lobbying the American government to import camels to settle the Western United States. His real hope was that they would order their camels from Afghanistan and send him there as a purchasing agent. Harlan convinced the government that camels would be a worthy investment (Secretary of War Jefferson Davis was particularly interested), but it decided that importing them from Africa would cost less than from Afghanistan. After the US Army discovered the resistance of American horses, mules, and cows to the aggressive camels, the Camel Corps was disbanded in 1863. The camels were set free in Arizona.

On May 1, 1849, Harlan married an Elizabeth Baker in Chester County, Pennsylvania.[138] As Miss Baker was a Quaker like Harlan, who had abandoned the pacifism of his faith during his time in Asia, her family was scandalized that she married a man who had fought in wars. In 1852, Harlan's wife bore a daughter, Sarah Victoria, whom he greatly loved, being by all accounts a doting father.[138] However, Harlan's massive unpublished manuscript telling his life story only mentions his wife once and very briefly at that, and he always carried with him a poem he had written in 1820 for Elizabeth Swaim until the day of his death.[138]

Harlan next decided that he would convince the government to buy Afghan grapes. He spent two years working on this venture, but the coming of the American Civil War prevented this.

American Civil War edit

Harlan then proposed to raise a regiment.

In 1861, when the American Civil War began, Harlan wrote to the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, declaring that "General Josiah Harlan" was ready and willing to fight for the Union against the Confederate States of America.[139] Macintyre noted: "The man who had trained the Afghan army and humbled the slaving warlord Murad Beg saw no reason why he should not go into battle, once more, with a private army. Bizarrely, nor did the authorities in Washington, and permission was duly granted for the formation of "Harlan's Light Cavalry". Harlan had no formal rank, no experience of the American army, and had no knowledge of modern warfare. He was also sixty-two years old, but gave his age as fifty-six".[139] He raised a Union regiment 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry[140] of which he was colonel,[141] but he was used to dealing with military underlings in the way an oriental prince would. This led to a messy court-martial, but the aging Harlan ended his service due to medical problems. Harlan collapsed on July 15, 1862, while serving in Virginia from the effects of a mixture of fever, dehydration, and dysentery, was ordered to give up command of his regiment, and was reluctantly invalided out of the United States Army on August 19, 1862, on the grounds he was "debilitated from diarrhea".[142]

Legacy edit

He wound up in San Francisco, working as a doctor, dying of tuberculosis in 1871. He was essentially forgotten. His remains were buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in San Francisco (now defunct), but were moved and his gravesite is unknown. However, Harlan proved to be an inspiration for Rudyard Kipling's 1888 short story "The Man Who Would Be King," which in its turn became a popular 1975 film starring Sean Connery and Michael Caine. Many critics have noted a close resemblance between Daniel Dravot, the hero of "The Man Who Would Be King" and Harlan. Both were ambitious adventurers burning to conquer a kingdom in Central Asia, both entered Afghanistan disguised as a Muslim holy man, both were Freemasons, both wanted to emulate Alexander the Great, and both were granted Afghan titles of nobility.[143]

However, Harlan had no counterpart to Peachey Carnehan, Dravot's sidekick, but the character of Carnehan was created by Kipling to explain to the narrator of "The Man Who Would Be A King" how Dravot was killed in Afghanistan. Kipling, who was a Freemason himself, had always said he received the inspiration for "The Man Who Would Be A King" while working as a journalist in 1880s India, saying that an unnamed Freemason had told him the stories that gave him the idea for "The Man Who Would Be King," which suggests that Harlan's adventures in Afghanistan were still being retold in Masonic lodges in India in the 1880s.[144]

Harlan also appears in George MacDonald Fraser's novel Flashman and the Mountain of Light.

Scott Reiniger, star of cult classic 1978 horror film Dawn of the Dead, is Harlan's great-great-great-grandson, and thus (as of 2004[update]) heir to the title Prince of Ghor.[145]

Works edit

- Harlan, Josiah (1842). A Memoir of India and Avghanistaun. Philadelphia: J. Dobson.

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ Frater, Alexander (25 April 2004). "A Yankee in the Great Game". The New York Times.

- ^ "Josiah the Great: The True Story of The Man Who Would Be King". benmacintyre.com. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ Singh, Sarbpreet (26 April 2019). "How a Quaker from America gained fame and fortune in Ranjit Singh's court (and was then banished)". Scroll.in. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 17.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 19.

- ^ "The Company That Ruled The Waves". The Economist. 17 December 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "The Company That Ruled The Waves". The Economist. 17 December 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 23.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 28.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 page 47.

- ^ Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 page 47.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 33.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 36.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 47.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 61.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 71.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 81–86.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 86.

- ^ Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 page 45.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 121.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 page 73

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 124.

- ^ Meyer, Karl & Brysac, Shareen Blair The Tournament of Shadows The Great Game and the Race of Empire in Central Asia, Washington: Counterpoint, 1999 page 68.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b c d Macintyre 2002, p. 166.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 125.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 127.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 130.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 131.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 132–133.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 133.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 142.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 144.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 page 73.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 152.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant Ranjit Singh Delhi: Penguin, 2008 pages 160-162.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant Ranjit Singh Delhi: Penguin, 2008, page 157.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant Ranjit Singh Delhi: Penguin, 2008 page 161.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 153.

- ^ Lafont, Jean-Marie (2001). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: The French Connections. Amritsar: Guru Nanak Dev University. p. 6.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 156.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 159.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 160.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 161.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 162.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 158.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 14, 166–167.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 167.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant Ranjit Singh Delhi: Penguin, 2008 pages 167-168.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant Ranjit Singh Delhi: Penguin, 2008 page 167.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 168.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 162–163.

- ^ a b c d Macintyre 2002, p. 165.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 172–173.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 173.

- ^ a b c d e Macintyre 2002, p. 176.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 175.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 177.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 178.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 179.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 182.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 184.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 185.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 185–187.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 187.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant Ranjit Singh Delhi: Penguin, 2008 page 167.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 190.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 191.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 192.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 201.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 191–192.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 193.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 194.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 196.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Meyer, Karl & Brysac, Shareen Blair The Tournament of Shadows The Great Game and the Race of Empire in Central Asia, Washington: Counterpoint, 1999 page 68.

- ^ Meyer, Karl & Brysac, Shareen Blair The Tournament of Shadows The Great Game and the Race of Empire in Central Asia, Washington: Counterpoint, 1999 page 68.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 200.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 197.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 202.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 202–203.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 205.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 211.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 217.

- ^ Meyer, Karl & Brysac, Shareen Blair The Tournament of Shadows The Great Game and the Race of Empire in Central Asia, Washington: Counterpoint, 1999 page 69.

- ^ Meyer, Karl & Brysac, Shareen Blair The Tournament of Shadows The Great Game and the Race of Empire in Central Asia, Washington: Counterpoint, 1999 page 69.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 219.

- ^ Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 page 446.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 220.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 225.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 230.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 231.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 233.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 234.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 210.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 204.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 248.

- ^ Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 pages 216-217.

- ^ Macintyre, pg. 258

- ^ Isani, Mukhtar Ali "Melville and the "Bloody Battle in Afghanistan"" pages 645-649 from American Quarterly, Volume 20, No. 3 Autumn, 968 pages 647-648.

- ^ Macintyre, pg. 265

- ^ Isani, Mukhtar Ali "Melville and the "Bloody Battle in Afghanistan"" pages 645-649 from American Quarterly, Volume 20, No. 3 Autumn, 968 pages 648-649.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2002, p. 267.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2002, p. 275.

- ^ Civil War Soldiers and Sailors listing

- ^ Civil War Soldiers and Sailors listing

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 284.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, pp. 289–290.

- ^ Macintyre 2002, p. 289.

- ^ "US movie actor is 'Afghan prince'". BBC News. BBC. 26 May 2004. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

References edit

- Macintyre, Ben (2002). The Man Who Would Be King: The First American in Afghanistan. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-20178-4.

- Macintyre, Ben (2004). Josiah the Great: The True story of the Man Who Would Be King. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-00-715107-1.

- Harlan, Josiah (1987). A Man of Enterprise: The Short Writings of Josiah Harlan. New York, NY, USA: Afghanistan Forum. OCLC 20388056.

External links edit

- Biography of Josiah Harlan

- US movie actor is 'Afghan prince', BBC

- A Yankee in the Great Game

- The Quaker who went on the Warpath