Summary

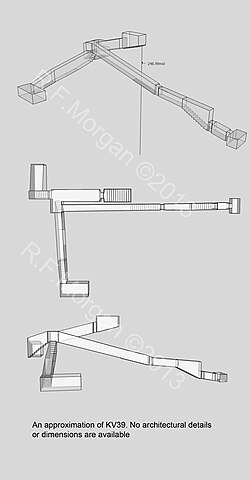

Tomb KV39 in Egypt's Valley of the Kings is one of the possible locations of the tomb of Pharaoh Amenhotep I. It is located high in the cliffs, away from the main valley bottom and other royal burials. It is in a small wadi that runs from the east side of Al-Qurn, directly under the ridge where the workmen's village of Deir el-Medina lies. The layout of the tomb is unique. It has two axes, one east and one south. Its construction seems to have occurred in three phases. It began as a simple straight axis tomb that never continued past the first room. In the subsequent phase, a series of long descending corridors and steps were cut to the east and south. It was discovered around 1900 by either Victor Loret or Macarious and Andraos but was not fully examined. It was excavated between 1989 and 1994 by John Rose and was further examined in 2002 by Ian Buckley. Based on the tomb's architecture and pottery found, it was likely cut in the early Eighteenth Dynasty, possibly for a queen. Fragmentary remains of burials were recovered from parts of the tomb but who they belong to is unknown. KV39's location may fit the description of the tomb of Amenhotep I given in the Abbott Papyrus but this is the subject of debate.

| KV39 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Unknown, possibly Amenhotep I | |

Schematic of KV39 | |

KV39 | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′11″N 32°36′02″E / 25.73639°N 32.60056°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | 1899 or 1900 |

| Excavated by | Victor Loret (1899) or Macarious and Andraos (1900) John Rose (1989-94) Ian Buckley (2002) |

| Decoration | Undecorated |

← Previous KV38 Next → KV40 | |

Location edit

KV39 is located to the south of the Valley of the Kings, high up at the head of a small valley above the tomb of Thutmose III, on the eastern side of Al-Qurn, the peak above the royal valley.[1][2] This kind of location, high in the cliffs and placed below a dry water course, is typical of tombs of the early Eighteenth Dynasty.[3]

Discovery and excavation edit

KV39 was discovered in 1899 or 1900 by Victor Loret[4] or by the Egyptian excavators Macarious and Andraos.[5][1] The tomb was visited by Arthur Weigall and others, and Weigall published a description of the tomb in 1911. Elizabeth Thomas drew a plan of the tomb in 1966 without entering it, finding the entrance was blocked by a large boulder.[1]

The tomb was first excavated between 1989 and 1994 by John Rose.[1] The stairs were cleared of the large rock and a large trench was dug in front of the tomb, uncovering miniature vessels placed in a pit 1 metre (3.3 ft) from the entrance. They bore the cartouches of Thutmose I, Thutmose II and Amenhotep II and represent a foundation deposit dating to the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty.[6] A stone wall was found at the top of the stairs, presumably constructed in the early 1900s to prevent debris from refilling the tomb during clearance work; a second wall had been built inside the tomb, replacing a section of steps cut from poor quality rock.[7]

Ian Buckley conducted further excavation and survey work in the tomb in 2002.[5] The tomb had been entered after the conclusion of Rose's work and refilled with debris washed in during the floods of 1994. The more unstable layers of rock had been affected by the water. The southern passageway was not excavated as sections of the ceiling had collapsed in addition to containing flood-washed fill. At the conclusion of the 2002 season the entrance was sealed with steel mesh and two stone walls were built to protect it from further flood action and prevent the intrusion of more debris.[8] The tomb had evidently seen human use in the past, based on the presence of soot from fires on the ceilings of the antechamber and upper burial chamber,[9] and the finds of rubbish such as newspapers and modern litter.[10]

Analysis of the pottery indicate a mix of early and later Eighteenth Dynasty styles.[11] At least part of the tomb had been used for burials. The entrance to the eastern passage showed signs of mud plaster, and large quantities of linen fabric, pottery, and fragments of coffins were found in the passageway and burial chamber.[12] The mummified remains show evidence of a high standard of mummification, including the use of padding inserted under the skin and fine quality textile wrapping.[13]

Architecture edit

KV39 is entered via a steep set of stairs that descend for 7 metres (23 ft). This opens onto to a descending corridor that leads a square hall, beyond which is a rectangular chamber that is entered via a low doorway.[14] A set of unfinished stairs are cut into the floor in this room.[15] Two further descending passageways run from the square hall. One, known as the east passage, begins at 180 degrees to the axis of the entrance. It is neatly cut and extends 38.33 metres (125.8 ft) through three steeply descending corridors and two staircases to a single rectangular chamber.[16] The other passageway extends to the south, at 90 degrees to the main axis. This passageway has not been fully cleared but it appears to be more roughly cut and descends steeply for a distance of about 25 metres (82 ft).[17]

The architectural layout of the tomb seems to have been altered several times and cut in different phases. It may have started as a simple corridor tomb,[18] or as a vertical shaft accessing a corridor and rectangular chamber.[2] The latter form is very similar to tomb ANA at Dra' Abu el-Naga dating to the late Seventeenth or early Eighteenth Dynasty.[2] Aston sees the southern extension to the tomb to be the second phase of construction,[19] while Buckley and colleagues consider it the last phase and represents an unfinished annex or a cache for royal mummies.[20] The southern passageway is very similar to TT358, tomb of Amenhotep I's sister Ahmose-Meritamun and TT320, the royal cache. Aston considers the third phase of construction to be the cutting of the east extension as it is similar in design to KV32, tomb of Thutmose IV's mother Tiaa, and presumably cut at around the same time as that tomb, during the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty in the reigns of Amenhotep II or Thutmose IV.[19]

The tomb is undecorated but mason's marks in red paint, used to guide the cutting of the tomb, are seen throughout on the ceilings and walls. Their locations and appearance are similar to those seen in the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty tombs of Thutmose III (KV34) and Amenhotep II (KV35).[21]

KV39 may be one of the earliest tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Its location is indicative of the early Eighteenth Dynasty,[3] as is its east-facing entrance, is something seen in royal Theban tombs before and during the early part of the Eighteenth Dynasty.[11] The various phases of its construction are similar to the tombs of early Eighteenth Dynasty royalty.[19] It certainly predates the tomb of Thutmose III as it lacks a protective well chamber.[22]

Intended occupant edit

It is unknown who the tomb was cut for but based on its architecture it was probably intended for a queen of the early Eighteenth Dynasty.[23] KV39 as the burial place of Amenhotep I was first suggested by Weigall in 1911. He drew on the location of that king's tomb as described in the Abbott Papyrus, as being 120 cubits (63 metres (207 ft)) from a feature called aḥay to the north of the "house of Amenhotep of the Garden".[24][25] The translation of aḥay is disputed and the other landmarks are not securely identified, but Weigall identified aḥay as the way station on the high path above KV39.[26][27]

Rose suggested KV39 was originally the tomb of Ahmose Inhapy and was later expanded by the cutting of the east passage for the reburial of Amenhotep I. This is based on inscriptions on the coffins of Ramesses I, Seti I, and Ramesses II which state they were moved from KV17 to the tomb of "Queen Inhapy in which Amenhotep I lay".[23]

See also edit

- Tomb ANB, another candidate for Amenhotep I's tomb

Citations edit

- ^ a b c d Rose 1992, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Aston 2015, p. 22.

- ^ a b Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 288.

- ^ a b Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Aston 2015, p. 34-35.

- ^ Rose 1992, p. 31-32.

- ^ Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 73-74.

- ^ Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 78-79.

- ^ Rose 1992, pp. 36.

- ^ a b Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 80.

- ^ Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 77, 81-82.

- ^ Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 79.

- ^ Rose 1992, p. 34.

- ^ Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 74.

- ^ Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 77.

- ^ Rose 1992, p. 35.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 89.

- ^ a b c Aston 2015, p. 23.

- ^ Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 81.

- ^ Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 75-79.

- ^ Buckley, Buckley & Cooke 2005, p. 72.

- ^ a b Aston 2015, p. 35.

- ^ Weigall 1911, p. 174-175.

- ^ Polz 1995, p. 9.

- ^ Polz 1995, p. 11.

- ^ Aston 2015, p. 36.

References edit

- Aston, David A (2015). Szafrański, Z. E. (ed.). "TT358, TT320 and KV39. Three Early Eighteenth Dynasty Queen's Tombs in the Vicinity of Deir el-Bahari" (PDF). Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean: Special Studies: Deir el-Bahari Studies. 24 (2): 15–42. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- Buckley, Ian M.; Buckley, Peter; Cooke, Ashley (2005). "Fieldwork in Theban Tomb KV 39: The 2002 Season". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 91: 71–82. ISSN 0307-5133.

- Polz, Daniel (1995). "The Location of the Tomb of Amenhotep I: A Reconsideration". In Wilkinson, Richard H. (ed.). Valley of the Sun Kings: New Explorations in the Tombs of the Pharaohs. United States: The University of Arizona Egyptian Expedition. pp. 8–21. ISBN 0-9649958-0-8. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- Reeves, C.N. (1990). Valley of the Kings : the decline of a royal necropolis. London: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 0-7103-0368-8.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs (2010 paperback ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28403-2. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- Rose, John (1992). "An Interim Report on Work in KV 39, September-October 1989". In Reeves, C.N. (ed.). After Tut'ankhamūn: Research and Excavation in the Royal Necropolis at Thebes (2009 ed.). pp. 28–40. ISBN 978-0-415-86171-7.

- Weigall, M. Arthur E. P. (1911). "Miscellaneous Notes". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. XI: 170–176. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

External links edit

- Theban Mapping Project: KV39 includes detailed maps of most of the tombs.