Summary

The kinetic inductance detector (KID) — also known as a microwave kinetic inductance detector (MKID) — is a type of superconducting photon detector first developed by scientists at the California Institute of Technology and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 2003.[1] These devices operate at cryogenic temperatures, typically below 1 kelvin. They are being developed for high-sensitivity astronomical detection for frequencies ranging from the far-infrared to X-rays.

Principle of operation edit

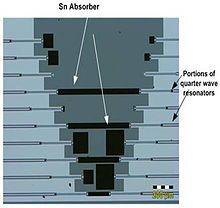

Photons incident on a strip of superconducting material break Cooper pairs and create excess quasiparticles. The kinetic inductance of the superconducting strip is inversely proportional to the density of Cooper pairs, and thus the kinetic inductance increases upon photon absorption. This inductance is combined with a capacitor to form a microwave resonator whose resonant frequency changes with the absorption of photons. This resonator-based readout is useful for developing large-format detector arrays, as each KID can be addressed by a single microwave tone and many detectors can be measured using a single broadband microwave channel, a technique known as frequency-division multiplexing.

Applications edit

KIDs are being developed for a range of astronomy applications, including millimeter and submillimeter wavelength detection at the Caltech Submillimeter Observatory,[2] the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) on the Llano de Chajnantor Observatory,[3] the CCAT Observatory, the Large Millimeter Telescope, and the IRAM 30-m telescope.[4] They are also being developed for optical and near-infrared detection at the Palomar Observatory.[5] KIDs have also flown on two balloon-borne telescopes, OLIMPO[6] in 2018 and BLAST-TNG[7] in 2020. KIDs have also gained popularity as a more compact, lower cost, and less complex alternative to transition edge sensors.[8]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Day, P. K.; LeDuc, H. G.; Mazin, B. A.; Vayonakis, A.; Zmuidzinas, J. (2003). "A broadband superconducting detector suitable for use in large arrays". Nature. 425 (6960): 817–821. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..817D. doi:10.1038/nature02037. PMID 14574407. S2CID 4414046.

- ^ Maloney, Philip R.; Czakon, Nicole G.; Day, Peter K.; Downes, Thomas P.; Duan, Ran; Gao, Jiansong; Glenn, Jason; Golwala, Sunil R.; Hollister, Matt I.; Leduc, Henry G.; Mazin, Benjamin A.; McHugh, Sean G.; Noroozian, Omid; Nguyen, Hien T.; Sayers, Jack; Schlaerth, James A.; Siegel, Seth; Vaillancourt, John E.; Vayonakis, Anastasios; Wilson, Philip; Zmuidzinas, Jonas (2010). "MUSIC for sub/Millimeter astrophysics" (PDF). In Holland, Wayne S.; Zmuidzinas, Jonas (eds.). Millimeter, Submillimeter, and Far-Infrared Detectors and Instrumentation for Astronomy V. Vol. 7741. Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE). pp. 77410F. doi:10.1117/12.857751. ISBN 9780819482310. S2CID 20865654.

- ^ Heyminck, S.; Klein, B.; Güsten, R.; Kasemann, C.; Baryshev, A.; Baselmans, J.; Yates, S.; Klapwijk, T. M. (2010). "Development of a MKID Camera for APEX". Twenty-First International Symposium on Space Terahertz Technology: 262. Bibcode:2010stt..conf..262H.

- ^ Monfardini, A.; et al. (2011). "A dual-band millimeter-wave kinetic inductance camera for the IRAM 30 m telescope". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 194 (2): 24. arXiv:1102.0870. Bibcode:2011ApJS..194...24M. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/194/2/24. S2CID 59407170.

- ^ Mazin, B. A.; O'Brien, K.; McHugh, S.; Bumble, B.; Moore, D.; Golwala, S.; Zmuidzinas, J. (2010). McLean, Ian S.; Ramsay, Suzanne K.; Takami, Hideki (eds.). "ARCONS: a highly multiplexed superconducting optical to near-IR camera". Proc. SPIE. Ground-based and Airborne Instrumentation for Astronomy III. 7735: 773518. arXiv:1007.0752. Bibcode:2010SPIE.7735E..18M. doi:10.1117/12.856440. S2CID 38654668.

- ^ Masi, S.; de Bernardis, P.; Paiella, A.; Piacentini, F.; Lamagna, L.; Coppolecchia, A.; Ade, P.A.R.; Battistelli, E.S.; Castellano, M.G.; Colantoni, I.; Columbro, F.; D'Alessandro, G.; Petris, M. De; Gordon, S.; Magneville, C. (2019-07-01). "Kinetic Inductance Detectors for the OLIMPO experiment: in-flight operation and performance". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2019 (07): 003–003. arXiv:1902.08993. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2019/07/003. ISSN 1475-7516.

- ^ "Science – BLAST The Experiment". sites.northwestern.edu. Retrieved 2023-12-17.

- ^ Zmuidzinas, Jonas (March 2012). "Superconducting Microresonators: Physics and Applications". Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics. 3: 169–214. doi:10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-020911-125022. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

External links edit

- SRON website on kinetic inductance detectors[permanent dead link]

- Research group of Prof. B. Mazin at UC Santa Barbara Archived 2010-12-03 at the Wayback Machine

- YouTube video on kinetic inductance from MIT

- Champlin, K.S.; Armstrong, D.B.; Gunderson, P.D. (1964). "Charge carrier inertia in semiconductors". Proceedings of the IEEE. 52 (6). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): 677–685. doi:10.1109/proc.1964.3049. ISSN 0018-9219.