Summary

La Superba (Y CVn, Y Canum Venaticorum) is a strikingly red giant star in the constellation Canes Venatici. It is a carbon star and semiregular variable.

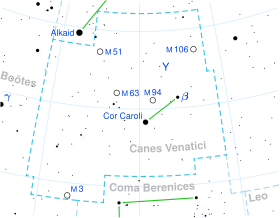

Location of Y Canum Venaticorum | |

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Canes Venatici |

| Right ascension | 12h 45m 07.826s[1] |

| Declination | +45° 26′ 24.93″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | +4.86 to +7.32[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Evolutionary stage | Asymptotic giant branch |

| Spectral type | C54J(N3)[3] |

| U−B color index | 6.62[4] |

| B−V color index | 2.54[4] |

| V−R color index | 1.75[5] |

| R−I color index | 1.38[5] |

| Variable type | SRb[3] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | 15.30[6] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −2.968[1] mas/yr Dec.: 13.063[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 3.2222 ± 0.1744 mas[1] |

| Distance | 1,010 ± 50 ly (310 ± 20 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −1.203[7] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 1.2[8] M☉ |

| Radius | 422[9] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 9,400[10] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | +0.23[8] cgs |

| Temperature | 2,600 - 3,200[11] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | −0.21[8] dex |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

Visibility edit

La Superba is a semiregular variable star, varying by about a magnitude over a roughly 160-day cycle, but with slower variation over a larger range. Periods of 194 and 186 days have been suggested, with a resonance between the periods.[11]

Y CVn is one of the reddest stars known, and it is among the brightest of the giant red carbon stars. It is the brightest of known J-stars, which are a very rare category of carbon stars that contain large amounts of carbon-13 (carbon atoms with 7 neutrons instead of the usual 6). The 19th century astronomer Angelo Secchi, impressed with its beauty, gave the star its common name,[12] which is now accepted by the International Astronomical Union.[14]

Properties edit

The angular diameter of La Superba has been measured at 13.81 mas.[15] It is expected to be pulsating but this has not been seen in the measurements. At 230 pc, this corresponds to a radius of 1.59 astronomical units (342 R☉).[a] If it were placed at the position of the Sun, the star's surface would extend beyond the orbit of Mars.

La Superba's temperature is believed to be about 2,760 K, making it one of the coolest true stars known. It is faintly visible to the naked eye, and the red colour is very obvious in binoculars.[12] When infrared radiation is included, Y CVn has a bolometric luminosity several thousand times that of the Sun. The mass of this type of star is difficult to determine; it would initially have been around 3 M☉ and somewhat less now due to mass loss. An estimate from Jim Kaler gives the star a luminosity between 22,000 and 87,000 L☉ and radius between 557 and 1,092 R☉ based on an assumed temperature of 3,000 K, and the author then classified it as a C7 or CN5 supergiant star although its mass is too low to be a true supergiant.[16]

Observations in the 60 and 100 micron infrared bands by the IRAS satellite showed that Y CVn is surrounded by a dust shell 0.9 parsecs in diameter. [17] This is one of the most prominent circumstellar dust shells detected in the IRAS all-sky survey.

Evolution edit

After stars up to a few times the mass of the sun have finished fusing hydrogen to helium in their core, they start to burn hydrogen in a shell outside a degenerate helium core, and expand dramatically into the red giant state. Once the core reaches a high enough temperature, it ignites violently in the helium flash, which begins helium core burning on the horizontal branch. Once even the core helium is exhausted, a degenerate carbon-oxygen core remains. Fusion continues in both hydrogen and helium shells at different depths in the star, and the star increases luminosity on the asymptotic giant branch (AGB). La Superba is currently an AGB star.

In the AGB stars, fusion products are moved outwards from the core by strong deep convection known as a dredge-up, thus creating a carbon abundance in the outer atmosphere where carbon monoxide and other compounds are formed. These molecules tend to absorb radiation at shorter wavelengths, resulting in a spectrum with even less blue and violet compared to ordinary red giants, giving the star its distinguished red color.[18]

La Superba is most likely in the final stages of fusing its remaining secondary fuel (helium) into carbon and shedding its mass at the rate of about a million times that of the Sun's solar wind. It is also surrounded by a 2.5 light year-wide shell of previously ejected material, implying that at one point it must have been losing mass as much as 50 times faster than it is now. La Superba thus appears almost ready to eject its outer layers to form a planetary nebula, leaving behind its core in the form of a white dwarf.[19]

Notes edit

- ^ 230 pc*sin(13.81 milliarcseconds) = 1.59 AU

References edit

- ^ a b c d e Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2021). "Gaia Early Data Release 3: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 649: A1. arXiv:2012.01533. Bibcode:2021A&A...649A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039657. S2CID 227254300. (Erratum: doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039657e). Gaia EDR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2009). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2007-2013)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/GCVS. Originally Published in: 2009yCat....102025S. 1: 02025. Bibcode:2009yCat....102025S.

- ^ a b Ducati, J. R. (2002). "VizieR On-line Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues. 2237: 0. Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D.

- ^ a b Y CVn

- ^ Gontcharov, G. A. (2006). "Pulkovo Compilation of Radial Velocities for 35 495 Hipparcos stars in a common system". Astronomy Letters. 32 (11): 759–771. arXiv:1606.08053. Bibcode:2006AstL...32..759G. doi:10.1134/S1063773706110065. S2CID 119231169.

- ^ Gontcharov, G. A. (2017). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Tycho-2 red giant branch and carbon stars (Gontcharov, 2011)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog. Bibcode:2017yCat..90370769G.

- ^ a b c Anders, F.; Khalatyan, A.; Chiappini, C.; Queiroz, A. B.; Santiago, B. X.; Jordi, C.; Girardi, L.; Brown, A. G. A.; Matijevic, G.; Monari, G.; Cantat-Gaudin, T.; Weiler, M.; Khan, S.; Miglio, A.; Carrillo, I.; Romero-Gómez, M.; Minchev, I.; de Jong, R. S.; Antoja, T.; Ramos, P.; Steinmetz, M.; Enke, H. (1 August 2019). "Photo-astrometric distances, extinctions, and astrophysical parameters for Gaia DR2 stars brighter than G = 18". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 628: A94. arXiv:1904.11302. Bibcode:2019A&A...628A..94A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201935765. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 131780028.

- ^ Kervella, Pierre; Arenou, Frédéric; Thévenin, Frédéric (2022). "Stellar and substellar companions from Gaia EDR3". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 657: A7. arXiv:2109.10912. Bibcode:2022A&A...657A...7K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202142146. S2CID 237605138.

- ^ Chandler, Colin Orion; et al. (2016). "The Catalog of Earth-Like Exoplanet Survey Targets (CELESTA): A Database of Habitable Zones Around Nearby Stars". The Astronomical Journal. 151 (3): 59. arXiv:1510.05666. Bibcode:2016AJ....151...59C. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/151/3/59. S2CID 119246448.

- ^ a b Neilson, Hilding R.; Ignace, Richard; Smith, Beverly J.; Henson, Gary; Adams, Alyssa M. (2014). "Evidence of a Mira-like tail and bow shock about the semi-regular variable V CVn from four decades of polarization measurements". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 568: A88. arXiv:1407.5644. Bibcode:2014A&A...568A..88N. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424037. S2CID 56232181.

- ^ a b c "50 Deep Sky Objects for 50mm Binoculars". Binocular Astronomy. Patrick Moore's Practical Astronomy Series. 2007. pp. 107–156. doi:10.1007/978-1-84628-788-6_9. ISBN 978-1-84628-308-6.

- ^ McCarthy, M. F. (1994). "Angelo Secchi and the Discovery of Carbon Stars". The MK Process at 50 Years. A Powerful Tool for Astrophysical Insight Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series. 60: 224. Bibcode:1994ASPC...60..224M.

- ^ "International Astronomical Union | IAU".

- ^ Quirrenbach, A.; Mozurkewich, D.; Hummel, C. A.; Buscher, D. F.; Armstrong, J. T. (1994). "Angular diameters of the carbon stars UU Aurigae, Y Canum Venaticorum, and TX PISCIUM from optical long-baseline interferometry". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 285: 541. Bibcode:1994A&A...285..541Q.

- ^ Jim Kaler. "La Superba". Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ^ Young, K.; Phillips, T. G.; Knapp, G. R. (1993). "Circumstellar Shells Resolved in IRAS Survey Data. II. Analysis". The Astrophysical Journal. 409: 725–738. Bibcode:1993ApJ...409..725Y. doi:10.1086/172702.

- ^ Abia, C.; Dominguez, I.; Gallino, R.; Busso, M.; Masera, S.; Straniero, O.; De Laverny, P.; Plez, B.; Isern, J. (2002). "S-Process Nucleosynthesis in Carbon Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 579 (2): 817–831. arXiv:astro-ph/0207245. Bibcode:2002ApJ...579..817A. doi:10.1086/342924. S2CID 15427160.

- ^ Libert, Y.; Gérard, E.; Le Bertre, T. (2007). "The formation of a detached shell around the carbon star Y CVn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 380 (3): 1161. arXiv:0706.4211. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.380.1161L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12154.x. S2CID 18486304.

External links edit

- https://web.archive.org/web/20051025230148/http://www.nckas.org/carbonstars/

- http://www.backyard-astro.com/deepsky/top100/11.html Archived 2012-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- http://jumk.de/astronomie/big-stars/la-superba.shtml