Summary

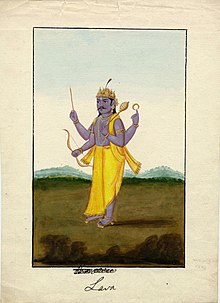

Lava (Sanskrit: लव, IAST: Lava)[1] and his elder twin brother Kusha, are the children of Rama and Sita in Hindu tradition.[2] Their story is recounted in the Hindu epic, Ramayana and its other versions. He is said to have a whitish golden complexion like their mother, while Kusha had a blackish complexion like their father.

| Lava | |

|---|---|

| King of Ayodhya | |

| |

| Maharaja of Kosala | |

| Predecessor | Rama |

| Successor | Atithi |

| Born | Valmiki Ashram, Brahmavart, Kosala (present-day Bithoor, Uttar Pradesh, India) |

| Spouse | Sumati (Ananda Ramayana) |

| Dynasty | Raghuvamsha-Suryavamsha |

| Father | Rama |

| Mother | Sita |

Birth and childhood edit

The first chapter of Ramayana, Balakanda, mentioned Valmiki narrating the Ramayana to his disciples, Lava and Kusha. But their birth and childhood story is mentioned in the last chapter 'Uttara Kanda' which is not believed to be the original work of Valmiki.[3][4] According to the legend, Sita banished herself from the kingdom due to the gossip of the kingdom folk about her chastity. She chose self-exile and took refuge in the ashram of Valmiki located on the banks of the Tamsa river.[5] Lava and Kusha were born at the ashram and were educated and trained in military skills under the teachings of Sage Valmiki. During this time they had also learned the story of Rama.

Sage Valmiki, along with Lava and Kusha, and a disguised Sita attend an ashvamedha yajna held by Rama.

In some versions of the epic, Lava and Kusha chanted the Ramayana in the presence of Rama and a vast audience. When Lava and Kusha recited about Sita's exile, Rama became grief-stricken and Valmiki produced Sita, testifying her innocence. Sita declared Lava and Kusha to be her sons and her fidelity to her husband. After Rama had expressed his desire to reconcile with her, Sita called upon the earth, her mother (Bhumi), to receive her and as the ground opened, she vanished into it. Even as he lamented the loss of his wife, Rama acknowledged his sons and sought their company.[6]

In some versions, Lava and Kusha capture the horse of the sacrifice and went to defeat Rama's brothers (Lakshmana, Bharata and Shatrughna) and their armies. When Rama came to fight with them, Sita intervenes and unites father and sons.

Later life edit

Lava and Kusha became rulers after their father Rama founded the cities of Lavapuri and Kasur, respectively. The king of Kosala, Rama, installed his son Lava at Shravasti and Kusha at Kushavati.[7]

In the Ananda Ramayana, Lava had a wife named Sumati,[8] and together the couple ruled the city of Lavapuri and the kingdom of Shravasti.

In popular culture edit

Lava is purported to have founded Lavapuri[9] (the modern day city of Lahore),[10] which is named after him.[11]

There is a temple associated with Lava (or Loh) inside Shahi Qila, Lahore.[12]

There are various communities and clans in modern India that claim descent from Lava, an example being the "Levas", a branch of which are the Lohana Kotecha and Leuva Marathas.[citation needed]

References edit

- ^ "Lohana History". Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Chandra Mauli Mani (2009). Memorable Characters from the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata. Northern Book Centre. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-81-7211-257-8.

- ^ "Uttara Kanda of Ramayana was edited during 5th century BCE - Puranas". BooksFact - Ancient Knowledge & Wisdom. 26 April 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Rao, T. S. Sha ma; Litent (1 January 2014). Lava Kusha. Litent.

- ^ Vishvanath Limaye (1984). Historic Rama of Valmiki. Gyan Ganga Prakashan.

- ^ Valmiki. The Ramayana. pp. 615–617.

- ^ Nadiem, Ihsan N (2005). Punjab: land, history, people. Al-Faisal Nashran. p. 111. ISBN 9789695034347. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ Ānanda Rāmāyaṇa: Sāra-kāṇḍa, Yātra-kāṇḍa, Yāga-kāṇḍa, Vilāsa-kāṇḍa, Janma-kāṇḍa, Vivāha-kāṇḍa. Parimal Publications. 2006. p. 425. ISBN 978-81-7110-283-9.

- ^ Bombay Historical Society (1946). Annual bibliography of Indian history and Indology, Volume 4. p. 257.

- ^ Baqir, Muhammad (1985). Lahore, past and present. B.R. Pub. Corp. pp. 19–20. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ Masudul Hasan (1978). Guide to Lahore. Ferozsons.

- ^ Ahmed, Shoaib. "Lahore Fort dungeons to re-open after more than a century." Daily Times. 3 November 2004.