Summary

The Legislative Council of Nova Scotia was the upper house of the legislature of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. It existed from 1838 to May 31, 1928. From the establishment of responsible government in 1848, members were appointed by the lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia on the advice of the premier.

Legislative Council of Nova Scotia | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Founded | 1838 |

| Disbanded | May 31, 1928 |

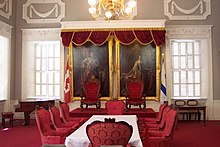

| Meeting place | |

| |

Before Confederation edit

The Legislative Council had its origins in the older unified Nova Scotia Council, created in 1719 and appointed in 1720,[1] which exercised a combination of executive and judicial functions.[2] Its functions were more formally specified in instructions issued by the Board of Trade in 1729.[3] The Council acted as the Governor's cabinet and as the province's General Court until the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia was established in 1754 (but its judicial function was not totally eliminated).[4] It assumed a legislative function in 1758, when the 1st General Assembly of Nova Scotia was called, by acting as its upper house.[4]

The constitution of the Council and its form of tenure changed from time to time, usually upon the issue of a Commission to an incoming Governor:

| Year | Instrument | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1729 | Instructions from the Board of Trade to Lieutenant-Governor Richard Philipps[5] |

|

| 1749 | Instructions to Edward Cornwallis[2] |

|

| 1764 | Commission appointing Montague Wilmot[2] |

|

| 1838 | Special Royal Commission to Lord Falkland Commission appointing Lord Durham as Governor-General[7] |

|

| 1846 | Commission appointing Earl Cathcart as Governor-General[8] |

|

| 1861 | Commission appointing Lord Monck as Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief, together with separate Instructions[9] |

|

During the period of 1845-1846, a sequence of ambiguous correspondence occurred between Lord Falkland and the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies (initially Edward Stanley, followed by William Ewart Gladstone), on the subject of granting life tenure to members of the Legislative Council. Cathcart's commission and instructions were, however, not formally changed.[10] In 1896, however, J.G. Bourinot expressed his opinion that the Crown had effectively yielded its right to appoint at pleasure, thus conferring a tenure for life, but he also conceded that the provincial legislature had the power to abolish the Council.[11]

Post-Confederation edit

The Nova Scotia Legislature codified the procedure of appointment in 1872, by specifying that they would be made by the Lieutenant-Governor under the Great Seal of the Province.[12] This was revised in 1900 to specify that the power of appointment rested with the Lieutenant-Governor in Council.[13]

Until 1882, the Executive Council normally included one Minister with portfolio and one Minister without portfolio from the Council.[14] During the administration of William Thomas Pipes, the practice was altered so that only the Government Leader in the Council would be appointed as a Minister without portfolio in the future.[14]

After 1899, the Council performed all its deliberations on bills solely in committee, after they had been given first reading. This effectively placed its work in obscurity, far from the public eye.[14]

1925 reform edit

With the Assembly seemingly unable to abolish the Legislative Council without its permission, it eventually came to consider reforming the Council as a next-best alternative. The first serious reform proposal was considered in 1916, when the Assembly passed a reform bill based on the Imperial Parliament Act 1911, which limited the veto of the House of Lords. The bill would have changed the Council's absolute veto to a suspensory veto; if the Assembly passed a bill in three successive legislative sessions over two years, the bill would go into effect notwithstanding the lack of the Council's consent. This bill, which was presented to the Council in the last days of the 1916 session at the height of the first World War, was received badly by the Council, which refused to pass it. A similar bill was considered by the Assembly the following year, but was dropped after the Council threatened not to pass any other bills sent to it by the Assembly.

The subject of abolition was revived in 1922, when the Assembly passed a resolution calling for the Legislative Council's resolution. Instead of sending an abolition bill to the Council, however, the Assembly formed a delegation to meet with members of the Legislative Council to consider methods of abolition. When the two delegations met together, the Assembly members were surprised that while the Councillors were unwilling to accept abolition, they were quite interested in potential reforms designed to make the Legislature work more effectively, including the possibility of electing the Council. As it was once again late in the legislative session, there was not sufficient time to negotiate a specific proposal, however. As such, the delegations requested permission from the Assembly and Council to continue working on the matter until the 1923 session. When the Legislature met again in 1923, the joint committee met again, but discussions once more led nowhere, as each group expected the other to offer a specific proposal.

During the 1924 session, the Assembly once more considered an abolition bill proposed by Howard William Corning, House Leader of the Conservative Party. After vehement debate, in which Liberal MHAs defended the Legislative Council as a bulwark against radicalism, the bill was defeated in the Assembly.

The following year, Premier Armstrong introduced a bill to reform the Legislative Council in three respects:

- it implemented a framework similar to that of the Parliament Act 1911;

- it limited the tenure of office of new appointees to the Council to ten years, although Councillors would be eligible for reappointment; and

- it imposed an age limit of seventy for new members and seventy-five for existing members.

After criticism from the Halifax Morning Chronicle, the bill was amended to drop the eligibility for reappointment. The amended bill passed the Assembly on a party line vote, and was sent to the Council, which further amended it to remove the age limit for sitting Councillors, increase the age limit for new appointees to seventy-five, and prohibit use of the new procedure to abolish the Council without its consent. The revised bill subsequently received Royal Assent.[15]

As the reform bill was passed barely a month before an election in which the Liberals were expected to do poorly, it was immediately criticized by Conservatives as a ploy to extend Liberal rule beyond the grave. When the Conservatives won a resounding victory, they almost immediately reopened plans to abolish the Legislative Council.

Abolition edit

Following the Conservative landslide in 1925, the Council abolition debate was reopened. The Conservatives' first Speech from the Throne in 1926 called for the abolition of the Council; a few weeks later, Premier Edgar Rhodes introduced an abolition bill in the Assembly. Meanwhile, Rhodes worked behind the scenes to try to negotiate for the Council to agree to abolish itself. In February, Rhodes offered the pre-reform Councillors pensions of $1000 per annum for ten years, and the post-reform Councillors $500 per annum for ten years; this proposal was rejected almost unanimously by the Council as a "bribe", and inspired the Council to pass a resolution affirming its important constitutional role.

With the Council seemingly unwilling to abolish itself, Rhodes considered alternative means of achieving abolition. In early March, he settled on a scheme to appoint twenty Councillors in addition to the eighteen already sitting in the Council. As the Council was presumed to be limited to twenty-one, this would have resulted in seventeen Councillors over and above the presumed constitutional limit. Wary of the constitutionality of the appointments, Lieutenant-Governor James Cranswick Tory wrote of the plan to Secretary of State in Ottawa, stating that he planned to make the appointments on March 15, 1926, unless instructed otherwise by the Governor General. After receiving an opinion from the Law Officers expressing the belief that the appointments in excess of twenty-one would be unconstitutional, the Governor General instructed Lieutenant-Governor Tory not to make the appointments for the time being, and suggested that the matter should be judicially considered.

Rebuffed by Ottawa, the Rhodes government then filed a reference for an advisory opinion with the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia. The reference presented four questions:

- Has the Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia, acting by and with the advice of the Executive Council of Nova Scotia, power or authority to appoint in the name of the Crown by instrument under the Great Seal of the Province so many Members of the Legislative Council of Nova Scotia that the total number of the Members of such Council holding their offices or places as such Members would

- (a) exceed twenty-one, or

- (b) exceed the total number of the Members of said Council who held their offices or places as such Members at the Union mentioned in Section 88 of The British North America Act, 1867?[16]

- Is the membership of the Legislative Council of Nova Scotia limited in number?

- Is the tenure of office of Members of the said Council appointed thereto prior to May 7, A.D. 1925, during pleasure or during good behaviour or for life?

- If such tenure is during pleasure, is it during the pleasure of His Majesty the King, or during the pleasure of His Majesty represented in that behalf by the Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia acting by and with the advice of the Executive Council of Nova Scotia?

In October 1926, the Nova Scotia Supreme Court issued a divided opinion,[17] in which:

- all judges agreed that a full Legislative Council consisted of 21 members;

- two judges ruled that the Lieutenant-Governor could appoint more than twenty-one Councillors, while two ruled that he could not;

- three of the four judges ruled that the Councillor's tenure of office was at pleasure, but only two ruled that it was at the pleasure of the Lieutenant-Governor, while the third judge ruled that they served at the pleasure of His Majesty the King; the fourth judge ruled that Councillors served for life.

With the court effectively evenly divided on all issues, it granted leave to appeal its ruling to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. In October 1927, the Board, in a decision written by Viscount Cave,[18] ruled that:

- from 1838 to 1867, there was nothing in any of the commissions to the Province's successive Governors that limited the number of Councillors that could be appointed, nor was there anything of that nature to be found in any other correspondence on the subject;

- the fact that s. 88 of the British North America Act 1867 continued the constitution of the Province's Legislature did not mean that the number of Councillors was to be frozen at a given number;

- Councillors were solely appointed at pleasure; and

- tenure is "during the pleasure of His Majesty represented in that behalf by the Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia acting by and with the advice of the Executive Council of Nova Scotia."

In the weeks before the 1928 legislative session, Rhodes dismissed all but one of the Liberal Councillors appointed before 1925 and appointed enough new Conservative members to reach the symbolic number of twenty-two (to emphasize the Lieutenant-Governor's constitutional right to increase the size of the Council). On February 24, 1928, the now Conservative-dominated Council passed an abolition bill sent to it days before by the Assembly.[19] Under the terms of the bill, the Council would be abolished as of May 31, 1928, so as to avoid any constitutional problems with legislation passed during the 1928 session.

See also edit

Further reading edit

- Bourinot, J.G. (May 20, 1896). "The Constitution of the Legislative Council of Nova Scotia". In Bourinot, J.G. (ed.). Proceedings and Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada. II. Vol. II. Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada. pp. 141–173 (Section II).

- Beck, J. Murray (1957). The Government of Nova Scotia. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-7001-9.

- Hoffman, C.P. (2011). The Abolition of the Legislative Council of Nova Scotia, 1925-1928 (LL.M.). Montreal: McGill University. SSRN 2273029.

References edit

- ^ Hoffman 2011, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Hoffman 2011, p. 29.

- ^ Hoffman 2011, p. 27.

- ^ a b Hoffman 2011, p. 30.

- ^ Hoffman 2011, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Hoffman 2011, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Hoffman 2011, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Hoffman 2011, p. 37.

- ^ Hoffman 2011, pp. 39–42.

- ^ Hoffman 2011, pp. 33–39.

- ^ Bourinot 1896, pp. 171–172.

- ^ An Act to provide for the appointment of Legislative Councillors in the Province of Nova Scotia, S.N.S. 1872, c. 13

- ^ Of the Constitution, Powers and Privileges of the Houses, R.S.N.S. 1900, c. 2, s. 2

- ^ a b c Beck 1957, ch. XV.

- ^ An Act to amend Chapter 2, Revised Statutes, 1923, "Of the Constitution, Powers and Privileges of the Houses", S.N.S. 1925, c. 16

- ^ British North America Act 1867, 1867, c. 3, s. 88

- ^ Reference re Legislative Council of Nova Scotia, (1926) 59 NSR 1

- ^ The Attorney General of Nova Scotia v The Legislative Council of Nova Scotia [1927] UKPC 92, [1928] AC 107 (18 October 1927), P.C. (on appeal from Nova Scotia)

- ^ An Act Abolishing the Legislative Council and Amending the Constitution of the Province, S.N.S. 1928, c. 1