Summary

The London conference of 1864 was a peace conference on the Second Schleswig War that took place in London from 25 April to 25 June 1864.

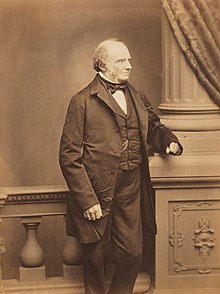

Lord Russell had intervened with a proposal that the war should be submitted to a European conference on behalf of the United Kingdom; the proposal was supported by the Russian Empire, the Second French Empire, and Sweden-Norway. The negotiations were influenced by the Prussian and Austrian victory in the Battle of Dybbøl, giving Otto von Bismarck and his delegation an advantage over their opponents. The conference broke up 25 June 1864 without having arrived at any conclusion.

Background edit

The government of Denmark attempted to integrate the Duchy of Schleswig, by creating a new common constitution (the so-called November Constitution) for Denmark and Schleswig. On 18 November 1863 Christian IX of Denmark signed the constitution, merging Schleswig into Denmark and separating Schleswig from the Duchy of Holstein. On 28 December a motion was introduced in the Federal Assembly by Austria and Prussia, calling on the German Confederation to occupy Schleswig as a pledge for the observance by Denmark of compacts of London Protocol 1852. This implied the recognition of the rights of Christian IX, and was indignantly rejected by Denmark; whereupon the Federal Assembly passed a Federal execution against Holstein and Saxe-Lauenburg, authorising the Austrian and Prussian governments to intervene.

Initially Lord Russell proposed a European conference based on status quo. The German powers signed an agreement on 11 March, under which the compacts of 1852 were declared to be no longer valid.[1]

The negotiations edit

The British plans for a ceasefire should have been presented on 12 April, but Bismarck was successful in postponing the opening of the conference to 25 April. Meanwhile, the German and Austrian troops had a decisive victory in the Battle of Dybbøl.

The proceedings of the conference only revealed the inextricable tangle of issues involved. The 11 March agreement made the Germans participate if the 1852 London Protocol was not taken as a basis, and the duchies were bound to Denmark by a personal tie only. Furthermore, the Germans demanded a Danish withdrawal of the blockade of the German ports. The Danish delegation refused, arguing that cutting off all maritime transport from and to the enemy was essential to the Danish strategy of war. [2] [3]

On 12 May 1864, the conference in London led to a ceasefire, which soon broke down, as the delegations could not agree on a clear fixing of the boundaries; partitioning the Duchy of Schleswig was seen as possible.[4] On 28 March, Lord Russell declared support for a Partition Plan that separated the German parts of Schleswig from the Danish monarchy. Napoleon III, a supporter of the self-determination principle, demanded a referendum.[5]

Beust, on behalf of the Confederation, demanded the recognition of the Augustenburg claimant; Austria leaned to a settlement on the lines of that of 1852. Prussia, it was increasingly clear, aimed at the acquisition of the duchies. The first step towards the realisation of that ambition was to secure the recognition of the absolute independence of the duchies, which Austria could not oppose because of the risk of forfeiting any influence among the German states. The two powers then, agreed to demand the complete political independence of the duchies bound together by common institutions.

The next move was uncertain. As to the question of annexation, Prussia would leave that open but made it clear that any settlement must involve the complete military subordination of Schleswig-Holstein to herself. That alarmed Austria, which had no wish to see a further extension of Prussia's already overgrown power and began to champion the claims of the duke of Augustenburg. That contingency, however, Bismarck had foreseen and himself offered to support the claims of the duke at the conference if he would undertake to subordinate himself in all naval and military matters to Prussia, surrender Kiel for the purposes of a Prussian war-harbour, give Prussia the control of the projected Kiel Canal, and enter the Prussian Zollverein. [6]

The Danish Foreign Minister, George Quaade, declared his country ready to follow “the road of peace” but had no answer from Copenhagen on the issues of the Partition Plan. On behalf of Prussia, Bismarck agreed in a partition of Schleswig, only leaving a minor part for Denmark. On 25 June the London conference broke up without having arrived at any conclusion. On the 24th, in view of the end of the truce, Austria and Prussia had arrived at a new agreement, the object of the war being now declared to be the complete separation of the duchies from Denmark. As the result of the short campaign that followed, the preliminaries of a treaty of peace were signed on August 1, the King of Denmark renouncing all his rights in the duchies in favour of the Emperor Francis Joseph I of Austria and King William I of Prussia.

References edit

- ^ Neergaard 1916, p. 995

- ^ Thorsen 1958, p. 291

- ^ Neergaard 1916, p. 1214

- ^ Neergaard 1916, p. 1221

- ^ Neergaard 1916, p. 1150

- ^ Beust: Mem. 1. 272

Further reading edit

- Carr, Carr. Schleswig-Holstein, 1815–1848: A Study in National Conflict (Manchester University Press, 1963).

- Price, Arnold. "Schleswig-Holstein" in Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions (2005) online

- Steefel, Lawrence D. The Schleswig-Holstein Question. 1863-1864 (Harvard U.P. 1923).

- Neergaard, N (1916), Under Junigrundloven,II,2 (:da), København-Kristiania: Gyldendalske Boghandel/Nordisk Forlag

- Thorsen, Svend (1958), De danske ministerier 1848-1901 Et hundrede politisk- historiske biografier (:da), København: Pensionsforsikringsanstalten

External links edit

- Historical Atlas of Schleswig-Holstein

- Searchable dictionary of German and Danish and Frisian forms of Schleswig placenames