Summary

MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor is a protein that in humans is encoded by the MYC gene[5] which is a member of the myc family of transcription factors. The protein contains basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) structural motif.

| MYC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | MYC, MRTL, MYCC, bHLHe39, c-Myc, v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog, MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor, Genes, myc, c-myc | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 190080 MGI: 97250 HomoloGene: 31092 GeneCards: MYC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Function edit

This gene is a proto-oncogene and encodes a nuclear phosphoprotein that plays a role in cell cycle progression, apoptosis and cellular transformation. The encoded protein forms a heterodimer with the related transcription factor MAX. This complex binds to the E box DNA consensus sequence and regulates the transcription of specific target genes. Amplification of this gene is frequently observed in numerous human cancers. Translocations involving this gene are associated with Burkitt lymphoma and multiple myeloma in human patients. There is evidence to show that translation initiates both from an upstream, in-frame non-AUG (CUG) and a downstream AUG start site, resulting in the production of two isoforms with distinct N-termini. [provided by RefSeq, Aug 2017].

As a drug target edit

Under normal circumstances, c-Myc through its bHLHZip domain heterodimerizes with other transcription factors such as MAD, MAX, and MNT. Myc/Max dimers activate gene transcription, while Mad/Max and Mnt/Max dimers inhibit the activity of Myc.[6] c-MYC is over expressed in the majority of human cancers and in cancers where it is overexpressed, it drives proliferation of cancer cells.[7][8]

A recombinant form of c-Myc called Omomyc in which four residues are mutated has been produced.[9] Omomyc heterodimers with c-Myc and inhibits c-Myc transcriptional activity. When the mouse cancer cell line NIH3T3 is treated with Omomyc, it inhibits proliferation.[9] In a mouse model of cancer in which cancer cells were genetically engineered to conditionally express Omomyc, Omomyc triggered tumor regression which was accompanied by reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis of the tumor tissue.[10]

The Omomyc displays high affinity for MAX (Myc-associated protein X) and for enhancer box element CACGTG DNA sequences, that result in the uncoupling of cellular proliferation from normal growth factor regulation and contribute to many of the phenotypic hallmarks of cancer.[11] Omomyc also can bind MYC monomers and prevent it entering the nucleus.[12]

The recombinantly produced Omomyc miniprotein has been developed as a drug (OMO-103) and is currently in clinical trials.[13]

References edit

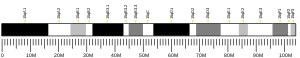

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000136997 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022346 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "MYC MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor [ Homo sapiens (human) ]". Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ Dang CV, McGuire M, Buckmire M, Lee WM (February 1989). "Involvement of the 'leucine zipper' region in the oligomerization and transforming activity of human c-myc protein". Nature. 337 (6208): 664–6. Bibcode:1989Natur.337..664D. doi:10.1038/337664a0. PMID 2645525. S2CID 4326525.

- ^ Madden SK, de Araujo AD, Gerhardt M, Fairlie DP, Mason JM (January 2021). "Taking the Myc out of cancer: toward therapeutic strategies to directly inhibit c-Myc". Molecular Cancer. 20 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/s12943-020-01291-6. PMC 7780693. PMID 33397405.

- ^ Dhanasekaran R, Deutzmann A, Mahauad-Fernandez WD, Hansen AS, Gouw AM, Felsher DW (January 2022). "The MYC oncogene - the grand orchestrator of cancer growth and immune evasion". Nature Reviews. Clinical Oncology. 19 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1038/s41571-021-00549-2. PMC 9083341. PMID 34508258.

- ^ a b Soucek L, Helmer-Citterich M, Sacco A, Jucker R, Cesareni G, Nasi S (November 1998). "Design and properties of a Myc derivative that efficiently homodimerizes". Oncogene. 17 (19): 2463–72. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202199. PMID 9824157. S2CID 22684888.

- ^ Soucek L, Whitfield J, Martins CP, Finch AJ, Murphy DJ, Sodir NM, Karnezis AN, Swigart LB, Nasi S, Evan GI (October 2008). "Modelling Myc inhibition as a cancer therapy". Nature. 455 (7213): 679–83. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..679S. doi:10.1038/nature07260. PMC 4485609. PMID 18716624.

- ^ Massó-Vallés D, Soucek L (April 2020). "Blocking Myc to Treat Cancer: Reflecting on Two Decades of Omomyc". Cells. 9 (4): 883. doi:10.3390/cells9040883. PMC 7226798. PMID 32260326.

- ^ Demma MJ, Mapelli C, Sun A, Bodea S, Ruprecht B, Javaid S, et al. (November 2019). "Omomyc Reveals New Mechanisms To Inhibit the MYC Oncogene". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 39 (22). doi:10.1128/MCB.00248-19. PMC 6817756. PMID 31501275.

- ^ "Results revealed from phase I clinical trial of the first drug to successfully inhibit the MYC gene, which drives many common cancers". European Organisation for. Research and Treatment of Cancer. 25 October 2022 – via EurekAlert!.

Further reading edit

- Hann SR, King MW, Bentley DL, Anderson CW, Eisenman RN (January 1988). "A non-AUG translational initiation in c-myc exon 1 generates an N-terminally distinct protein whose synthesis is disrupted in Burkitt's lymphomas". Cell. 52 (2): 185–95. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90507-7. PMID 3277717. S2CID 3012009.

- Hiyama T, Haruma K, Kitadai Y, Ito M, Masuda H, Miyamoto M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Shimamoto F, Chayama K (2001). "c-myc gene mutation in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma". Oncol. Rep. 8 (2): 289–92. doi:10.3892/or.8.2.289. PMID 11182042.

- Ruf IK, Rhyne PW, Yang H, Borza CM, Hutt-Fletcher LM, Cleveland JL, Sample JT (2001). "EBV Regulates c-MYC, Apoptosis, and Tumorigenicity in Burkitt's Lymphoma". Epstein-Barr Virus and Human Cancer. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 258. pp. 153–60. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-56515-1_10. ISBN 978-3-642-62568-8. PMID 11443860.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Hu HM, Arcinas M, Boxer LM (March 2002). "A Myc-associated zinc finger protein-related factor binding site is required for the deregulation of c-myc expression by the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene enhancers in Burkitt's lymphoma". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (12): 9819–24. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111426200. PMID 11777933.

- Hilker M, Tellmann G, Buerke M, Moersig W, Oelert H, Lehr HA, Hake U (2001). "Expression of the proto-oncogene c-myc in human stenotic aortocoronary bypass grafts". Pathol. Res. Pract. 197 (12): 811–6. doi:10.1078/0344-0338-00164. PMID 11795828.

- Feng XH, Liang YY, Liang M, Zhai W, Lin X (January 2002). "Direct interaction of c-Myc with Smad2 and Smad3 to inhibit TGF-beta-mediated induction of the CDK inhibitor p15(Ink4B)". Mol. Cell. 9 (1): 133–43. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00430-0. PMID 11804592.

- Kuschak TI, Kuschak BC, Taylor CL, Wright JA, Wiener F, Mai S (January 2002). "c-Myc initiates illegitimate replication of the ribonucleotide reductase R2 gene". Oncogene. 21 (6): 909–20. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205145. PMID 11840336.

- Chettab K, Zibara K, Belaiba SR, McGregor JL (January 2002). "Acute hyperglycaemia induces changes in the transcription levels of 4 major genes in human endothelial cells: macroarrays-based expression analysis". Thromb. Haemost. 87 (1): 141–8. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1612957. PMID 11848444. S2CID 22124540.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.