Summary

The Malaspina Glacier (Tlingit: Sít' Tlein) in southeastern Alaska is the largest piedmont glacier in the world. Situated at the head of the Alaska Panhandle, it is about 65 km (40 mi) wide and 45 km (28 mi) long, with an area of some 3,900 km2 (1,500 sq mi),[1] approximately the same size as the state of Rhode Island.

| Malaspina Glacier | |

|---|---|

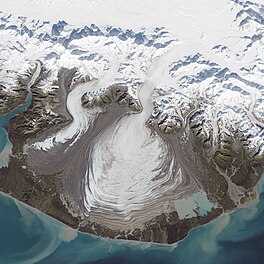

Malaspina Glacier captured by Landsat 8 on September 24, 2014 | |

Malaspina Glacier | |

| Type | Piedmont |

| Location | Alaska |

| Coordinates | 59°55′09″N 140°31′58″W / 59.91917°N 140.53278°W |

| Area | 3,900 km2 (1,500 sq mi) |

| Length | 45 km (28 mi) |

| Thickness | 600 meters (2,000 ft) |

| Designated | 1969 |

|

Name

edit

The Lingít name translates to Big Glacier. The colonial name for the glacier is in honor of Alessandro Malaspina, a Tuscan explorer in the service of the Spanish Navy, who visited the region in 1791. In 1874, W. H. Dall of the United States Coast Survey bestowed the name "Malaspina Plateau" on it, not realizing its true geological character.[2] Geography editThe Malaspina Glacier actually comprises Seward Glacier, Agassiz Glacier, and Marvine/Hayden Glacier, which converge as they spill out from the Saint Elias Mountains onto the coastal plain facing the Gulf of Alaska between Icy Bay and Yakutat Bay.[1] Officially, these three glaciers are classified independently, such that Malaspina Glacier does not technically exist.[3] The three glaciers are almost always referred to together, though sometimes only the largest primary piedmont lobe is referred to as Malaspina Glacier. This notable feature is actually part of Seward Glacier, with Agassiz Glacier contributing the secondary piedmont lobe to the west, and Marvine/Hayden Glacier constituting the smallest and most eastern lobe. Although the glaciers fill the plain, nowhere do they actually reach the water and so do not qualify as a tidewater glaciers. Notably, both Seward Glacier and Marvine/Hayden Glaciers terminate near Malaspina Lake, formed during a previous advance. Neither glacier actually terminates in the lake, and therefore are also not classified as lacustrine glaciers. The Malaspina is up to 600 meters (2,000 ft) thick in places, with the elevation of its bottom being estimated to be as much as 300 m (980 ft) below sea level.[4] There are two lakes on its margins: Oily Lake to the northwest, at the foot of the Samovar Hills between the Agassiz and Seward glaciers, and Malaspina Lake to the southeast, close to Yakutat Bay. Nearly all of the glacier is encompassed by the southeast lobe of the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. History editRadar data and aerial photographs dating back to 1972 provide evidence that the Malaspina-Seward glacier system lost about 20 m (66 ft) of its thickness between 1980 and 2000; because the glacier is so large, that amount of shrinkage was sufficient to contribute 0.5% of the rise in the global sea level.[5] In October 1969, the glacier became a National Natural Landmark.[6] See also editWikimedia Commons has media related to Malaspina Glacier. Notes edit

External links edit

| |