Summary

Mammals normally have a pair of eyes. Although mammalian vision is not so excellent as bird vision, it is at least dichromatic for most of mammalian species, with certain families (such as Hominidae) possessing a trichromatic color perception.

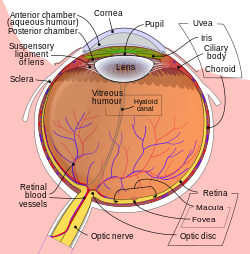

| Eye | |

|---|---|

Schematic diagram of the human eye. | |

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | oculus (plural: oculi) |

| Anatomical terminology [edit on Wikidata] | |

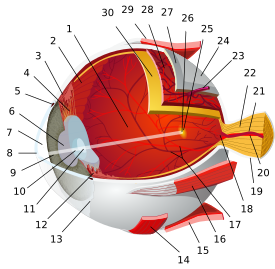

- posterior segment

- ora serrata

- ciliary muscle

- ciliary zonules

- Schlemm's canal

- pupil

- anterior chamber

- cornea

- iris

- lens cortex

- lens nucleus

- ciliary process

- conjunctiva

- inferior oblique muscle

- inferior rectus muscle

- medial rectus muscle

- retinal arteries and veins

- optic disc

- dura mater

- central retinal artery

- central retinal vein

- optic nerve

- vorticose vein

- bulbar sheath

- macula

- fovea

- sclera

- choroid

- superior rectus muscle

- retina

The dimensions of the eyeball vary only 1–2 mm among humans. The vertical axis is 24 mm; the transverse being larger. At birth it is generally 16–17 mm, enlarging to 22.5–23 mm by three years of age. Between then and age 13 the eye attains its mature size. It weighs 7.5 grams and its volume is roughly 6.5 ml. Along a line through the nodal (central) point of the eye is the optic axis, which is slightly five degrees toward the nose from the visual axis (i.e., that going towards the focused point to the fovea).

Three layers edit

The structure of the mammalian eye has a laminar organization that can be divided into three main layers or tunics whose names reflect their basic functions: the fibrous tunic, the vascular tunic, and the nervous tunic.[1][2][3]

- The fibrous tunic, also known as the tunica fibrosa oculi, is the outer layer of the eyeball consisting of the cornea and sclera.[4] The sclera gives the eye most of its white color. It consists of dense connective tissue filled with the protein collagen to both protect the inner components of the eye and maintain its shape.[5]

- The vascular tunic, also known as the tunica vasculosa oculi or the "uvea", is the middle vascularized layer which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid.[4][6][7] The choroid contains blood vessels that supply the retinal cells with necessary oxygen and remove the waste products of respiration. The choroid gives the inner eye a dark color, which prevents disruptive reflections within the eye. The iris is seen rather than the cornea when looking straight in one's eye due to the latter's transparency, the pupil (central aperture of iris) is black because there is no light reflected out of the interior eye. If an ophthalmoscope is used, one can see the fundus, as well as vessels (which supply additional blood flow to the retina) especially those crossing the optic disk—the point where the optic nerve fibers depart from the eyeball—among others[8]

- The nervous tunic, also known as the tunica nervosa oculi, is the inner sensory layer which includes the retina.[4][7]

- Contributing to vision, the retina contains the photosensitive rod and cone cells and associated neurons. To maximise vision and light absorption, the retina is a relatively smooth (but curved) layer. It has two points at which it is different; the fovea and optic disc. The fovea is a dip in the retina directly opposite the lens, which is densely packed with cone cells. It is largely responsible for color vision in humans, and enables high acuity, such as is necessary in reading. The optic disc, sometimes referred to as the anatomical blind spot, is a point on the retina where the optic nerve pierces the retina to connect to the nerve cells on its inside. No photosensitive cells exist at this point, it is thus "blind". Continuous with the retina are the ciliary epithelium and the posterior epithelium of the iris.

- In addition to the rods and cones, a small proportion (about 1-2% in humans) of the ganglion cells in the retina are themselves photosensitive through the pigment melanopsin. They are generally most excitable by blue light, about 470–485 nm. Their information is sent to the SCN (suprachiasmatic nuclei), not to the visual center, through the retinohypothalamic tract which is formed as melanopsin-sensitive axons exit the optic nerve. It is primarily these light signals which regulate circadian rhythms in mammals and several other animals.[9] Many, but not all, totally blind individuals have their circadian rhythms adjusted daily in this way. The ipRGCs have other functions as well, such as signaling the need for changing the diameter of the pupil in changing light conditions.

Anterior and posterior segments edit

The mammalian eye can also be divided into two main segments: the anterior segment and the posterior segment.[10]

The human eye is not a plain sphere but is like two spheres combined, a smaller, more sharply curved one and a larger lesser curved sphere. The former, the anterior segment is the front sixth[8] of the eye that includes the structures in front of the vitreous humour: the cornea, iris, ciliary body, and lens.[6][11]

Within the anterior segment are two fluid-filled spaces:

- the anterior chamber between the posterior surface of the cornea (i.e. the corneal endothelium) and the iris.

- the posterior chamber between the iris and the front face of the vitreous.[6]

Aqueous humor fills these spaces within the anterior segment and provides nutrients to the surrounding structures.

Some ophthalmologists specialize in the treatment and management of anterior segment disorders and diseases.[11]

The posterior segment is the back five-sixths[8] of the eye that includes the anterior hyaloid membrane and all of the optical structures behind it: the vitreous humor, retina, choroid, and optic nerve.[12]

The radii of the anterior and posterior sections are 8 mm and 12 mm, respectively. The point of junction is called the limbus.

On the other side of the lens is the second humour, the aqueous humour, which is bounded on all sides by the lens, the ciliary body, suspensory ligaments and by the retina. It lets light through without refraction, helps maintain the shape of the eye and suspends the delicate lens. In some animals, the retina contains a reflective layer (the tapetum lucidum) which increases the amount of light each photosensitive cell perceives, allowing the animal to see better under low light conditions.

The tapetum lucidum, in animals that have it, can produce eyeshine, for example as seen in cat eyes at night. Red-eye effect, a reflection of red blood vessels, appears in the eyes of humans and other animals that have no tapetum lucidum, hence no eyeshine, and rarely in animals that have a tapetum lucidum. The red-eye effect is a photographic effect, not seen in nature.

Some ophthalmologists specialise in this segment.[13]

Extraocular anatomy edit

Lying over the sclera and the interior of the eyelids is a transparent membrane called the conjunctiva. It helps lubricate the eye by producing mucus and tears. It also contributes to immune surveillance and helps to prevent the entrance of microbes into the eye.[14]

In many animals, including humans, eyelids wipe the eye and prevent dehydration.[15] They spread tears on the eyes, which contains substances which help fight bacterial infection as part of the immune system. Some species have a nictitating membrane for further protection. Some aquatic animals have a second eyelid in each eye which refracts the light and helps them see clearly both above and below water. Most creatures will automatically react to a threat to its eyes (such as an object moving straight at the eye, or a bright light) by covering the eyes, and/or by turning the eyes away from the threat. Blinking the eyes is, of course, also a reflex.

In many animals, including humans, eyelashes prevent fine particles from entering the eye. Fine particles can be bacteria, but also simple dust which can cause irritation of the eye, and lead to tears and subsequent blurred vision.[16]

In many species, the eyes are inset in the portion of the skull known as the orbits or eyesockets. This placement of the eyes helps to protect them from injury. For some, the focal fields of the two eyes overlap, providing them with binocular vision. Although most animals have some degree of binocular vision the amount of overlap largely depends on behavioural requirements.

In humans, the eyebrows redirect flowing substances (such as rainwater or sweat) away from the eye.

Function of the mammalian eye edit

The structure of the mammalian eye owes itself completely to the task of focusing light onto the retina. This light causes chemical changes in the photosensitive cells of the retina, the products of which trigger nerve impulses which travel to the brain.

In the human eye, light enters the pupil and is focused on the retina by the lens. Light-sensitive nerve cells called rods (for brightness), cones (for color) and non-imaging ipRGC (intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells) react to the light. They interact with each other and send messages to the brain. The rods and cones enable vision. The ipRGCs enable entrainment to the Earth's 24-hour cycle, resizing of the pupil and acute suppression of the pineal hormone melatonin.

Retina edit

The retina contains three forms of photosensitive cells, two of them important to vision, rods and cones, in addition to the subset of ganglion cells involved in adjusting circadian rhythms and pupil size but probably not involved in vision.

Though structurally and metabolically similar, the functions of rods and cones are quite different. Rod cells are highly sensitive to light, allowing them to respond in dim light and dark conditions; however, they cannot detect color differences. These are the cells that allow humans and other animals to see by moonlight, or with very little available light (as in a dark room). Cone cells, conversely, need high light intensities to respond and have high visual acuity. Different cone cells respond to different wavelengths of light, which allows an organism to see color. The shift from cone vision to rod vision is why the darker conditions become, the less color objects seem to have.

The differences between rods and cones are useful; apart from enabling sight in both dim and light conditions, they have further advantages. The fovea, directly behind the lens, consists of mostly densely packed cone cells. The fovea gives humans a highly detailed central vision, allowing reading, bird watching, or any other task which primarily requires staring at things. Its requirement for high intensity light does cause problems for astronomers, as they cannot see dim stars, or other celestial objects, using central vision because the light from these is not enough to stimulate cone cells. Because cone cells are all that exist directly in the fovea, astronomers have to look at stars through the "corner of their eyes" (averted vision) where rods also exist, and where the light is sufficient to stimulate cells, allowing an individual to observe faint objects.

Rods and cones are both photosensitive, but respond in different ways to different frequencies of light. They contain different pigmented photoreceptor proteins. Rod cells contain the protein rhodopsin and cone cells contain different proteins for each color-range. The process through which these proteins go is quite similar — upon being subjected to electromagnetic radiation of a particular wavelength and intensity, the protein breaks down into two constituent products. Rhodopsin, of rods, breaks down into opsin and retinal; iodopsin of cones breaks down into photopsin and retinal. The breakdown results in the activation of Transducin and this activates cyclic GMP Phosphodiesterase, which lowers the number of open Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels on the cell membrane, which leads to hyperpolarization; this hyperpolarization of the cell leads to decreased release of transmitter molecules at the synapse.

Differences between the rhodopsin and the iodopsins is the reason why cones and rods enable organisms to see in dark and light conditions — each of the photoreceptor proteins requires a different light intensity to break down into the constituent products. Further, synaptic convergence means that several rod cells are connected to a single bipolar cell, which then connects to a single ganglion cell by which information is relayed to the visual cortex. This convergence is in direct contrast to the situation with cones, where each cone cell is connected to a single bipolar cell. This divergence results in the high visual acuity, or the high ability to distinguish detail, of cone cells compared to rods. If a ray of light were to reach just one rod cell, the cell's response may not be enough to hyperpolarize the connected bipolar cell. But because several "converge" onto a bipolar cell, enough transmitter molecules reach the synapses of the bipolar cell to hyperpolarize it.

Furthermore, color is distinguishable due to the different iodopsins of cone cells; there are three different kinds, in normal human vision, which is why we need three different primary colors to make a color space.

A small percentage of the ganglion cells in the retina contain melanopsin and, thus, are themselves photosensitive. The light information from these cells is not involved in vision and it reaches the brain not directly via the optic nerve but via the retinohypothalamic tract, the RHT. By way of this light information, the body clock's inherent approximate 24-hour cycling is adjusted daily to nature's light/dark cycle. Signals from these photosensitive ganglion cells have at least two other roles in addition. They exercise control over the size of the pupil, and they lead to acute suppression of melatonin secretion by the pineal gland.

Accommodation edit

The purpose of the optics of the mammalian eye is to bring a clear image of the visual world onto the retina. Because of limited depth of field of the mammalian eye, an object at one distance from the eye might project a clear image, while an object either closer to or further from the eye will not. To make images clear for objects at different distances from the eye, its optical power needs to be changed. This is accomplished mainly by changing the curvature of the lens. For distant objects, the lens needs to be made flatter; for near objects the lens needs to be made thicker and more rounded.

Water in the eye can alter the optical properties of the eye and blur vision. It can also wash away the tear fluid—along with it the protective lipid layer—and can alter corneal physiology, due to osmotic differences between tear fluid and freshwater. Osmotic effects are made apparent when swimming in freshwater pools, because the osmotic gradient draws water from the pool into the corneal tissue (the pool water is hypotonic), causing edema, and subsequently leaving the swimmer with "cloudy" or "misty" vision for a short period thereafter. The edema can be reversed by irrigating the eye with hypertonic saline which osmotically draws the excess water out of the eye.

References edit

- ^ "The Eye." Accessed October 23, 2006.

- ^ "General Anatomy of the Eye." Accessed October 23, 2006.

- ^ "Eye Anatomy and Function." Accessed October 23, 2006.

- ^ a b c Cline D; Hofstetter HW; Griffin JR. Dictionary of Visual Science. 4th ed. Butterworth-Heinemann, Boston 1997. ISBN 0-7506-9895-0

- ^ X. The Organs of the Senses and the Common Integument. 1c. 1. The Tunics of the Eye. Gray, Henry. 1918. Anatomy of the Human Body

- ^ a b c Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. Dictionary of Eye Terminology. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company, 1990.

- ^ a b "Medline Encyclopedia: Eye." Accessed October 25, 2006.

- ^ a b c "eye, human."Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD 5 Apr. 2008

- ^ Tu DC, Zhang D, Demas J, et al. (December 2005). "Physiologic diversity and development of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells". Neuron. 48 (6): 987–99. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.031. PMID 16364902.

Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) mediate numerous nonvisual phenomena, including entrainment of the circadian clock to light-dark cycles, pupillary light responsiveness, and light-regulated hormone release.

- ^ Ocular Anatomy – Anterior Segment Archived 2008-09-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Departments. Anterior segment." Archived 2006-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Cantabrian Institute of Ophthalmology.

- ^ "Posterior segment anatomy". Archived from the original on 2016-06-03. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ Vitreoretinal Disease & Surgery – New England Eye Center

- ^ Shumway, Caleb L.; Motlagh, Mahsaw; Wade, Matthew (2022), "Anatomy, Head and Neck, Eye Conjunctiva", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30137787, retrieved 2022-11-02

- ^ Smith, Michael (2017-08-24). "The eyelid". Vision Eye Institute. Retrieved 2022-11-02.

- ^ Smith, Michael (2017-08-26). "The eyelashes". Vision Eye Institute. Retrieved 2022-11-02.