Summary

Marguerite Agniel (1891 – c. 1971) was a Broadway actress and dancer, who then became a health and beauty guru in New York in the early 20th century. She is known for her 1931 book The Art of the Body: Rhythmic Exercise for Health and Beauty, one of the first to combine yoga and nudism.

Marguerite Agniel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 21, 1891 |

| Died | Circa 1971 |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Actress, dancer |

After appearing in Vogue in 1926, she wrote for Physical Culture and other magazines. In the 1930s, she published a series of books, including Body Sculpture and Your Figure, advocating health and beauty practices, illustrated mainly with photographs of herself.

Agniel stated that her dance technique derived from Ruth St. Denis (who had followed François Delsarte), while her "aesthetic athletics" came mainly from the physical culture advocate, Bernarr Macfadden. She described the sexologist Havelock Ellis and the musicologist Sigmund Spaeth as major influences.

Early life edit

Marguerite, born January 21, 1891, Marguerite was born January 21, 1891, one of the six children of George Agniel and Ada Lescher Flowers. Her father was an Indiana farmer. He died in 1893 while she was an infant, leaving her mother to raise the children alone.[1] The Agniel family was French-Jewish; her mother's family was English.[2] She was married in New York on March 21, 1917.[3]

She performed in Broadway plays including The Amber Empress with music by Zoel Parenteau in 1916, and Raymond Hitchcock's Pin Wheel in 1922.[4][5]

Author edit

She appeared in the November 15, 1926, issue of Vogue, demonstrating slimming exercises in the form of floor stretches, with postures close to the yoga asanas Salabhasana, Supta Virasana, Sarvangasana and Halasana.[6] She wrote for Physical Culture magazine in 1927 and 1928.[7]

In 1931 Agniel wrote the book The Art of the Body: Rhythmic Exercise for Health and Beauty, illustrated mainly with photographs of herself;[8][9] she notes in the preface that her dance technique derives from Ruth St. Denis (who in turn followed François Delsarte), but that her "system of 'aesthetic athletics'"[10] was based mainly on that of Bernarr Macfadden, an advocate of physical culture. She names the sexologist Havelock Ellis and the musicologist Sigmund Spaeth as major influences, stating that both had shown "an extraordinarily intuitive understanding"[10] of her work.[10]

Agniel wrote a piece called "The Mental Element in Our Physical Well-Being" for The Nudist, an American magazine, in 1938; it showed nude women practising yoga, accompanied by a text on attention to the breath. The social historian Sarah Schrank comments that it made perfect sense at this stage of the development of yoga in America to combine nudism and yoga, as "both were exercises in healthful living; both were countercultural and bohemian; both highlighted the body; and both were sensual without being explicitly erotic."[11][12]

-

In "Buddha position", Muktasana. Photograph by John de Mirjian, c. 1928

-

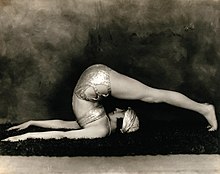

In Supta Virasana, demonstrating "A good exercise for the back and abdominal muscles". Photograph by John de Mirjian, c. 1928

-

"As Mona Lisa" by Robert Henri, c. 1929

-

Topless, c. 1923

Reception edit

Her friend the sexologist Havelock Ellis wrote in a letter to Louise Stevens Bryant (May 17, 1936) that Agniel's books were "full of beautiful illustrations, nearly all of herself. She has a wonderful art of posing, & they are largely nudes, though she is no longer young."[2]

Agniel is depicted in an "elegant, though sharply ironic"[13] Palladium photographic print by the Canadian photographer Margaret Watkins, "Head and Hand". It shows her hand holding a portrait sculpture head of herself by Jo Davidson.[13] This was one in a series of portraits of Agniel by Watkins that Agniel used in The Art of the Body. Devon Smither describes Agniel as "a leading health and beauty guru",[14] and the Art of the Body as "a moralizing exercise manual" providing a mixture of exercises, advice on cosmetics, and spiritual guidance.[14]

The scholars Mary O'Connor and Katherine Tweedie comment on Watkins's portraits of Agniel that they were circulated sometimes as artistic "nudes", sometimes as portraits, and sometimes as instances of "a regime of exercise and body modification".[15] They write that since Agniel chose to use these photographs of herself, she is presenting them "not as the passive victim of an objectifying male gaze ... but as the means of promulgating her own vision of the world and her own expertise. She circulates her body as an image of the ideal and for commercial profit."[15]

Works edit

- 1931 The Art of the Body. London: Batsford.

- 1931 "Dancing Mothers and Dancing Daughters", Hygeia 9:344-348

- 1933 Body Sculpture. New York: E.H. & A.C. Friedrichs.

- 1936 Your Figure. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran & Company.

- ——— also published in 1936 as Creating Body Beauty, New York: Bernard Ackerman.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Bateman, Dominique; Pikaart, Miranda (2020). "Biographical Sketch of Lucille Agniel Calmes". Online Biographical Dictionary of Militant Woman Suffragists, 1913–1920. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Ellis, Havelock. "Letters to an American". Virginia Quarterly Review (Spring 1940).

- ^ Married March 21, 1917, Manhattan New York, certificate no. 9261. Index to New York City Marriages, 1866–1937.

- ^ "Marguerite Agniel". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ "Zoel Parenteau, Stage Composer". The New York Times. September 15, 1972. p. 40.

- ^ Peters, Lauren Downing (May 31, 2018). Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder: Constructing the Fat, Female Body in American Fashion in the Age of Standardization, 1915–1930 (PDF). Stockholm University (D. Phil. Thesis). pp. 305, 307.

- ^ "au:Marguerite Agniel". WorldCat. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ King, Jay W. (February 10, 2020). Past Masters of the Nude: An Illustrated Bibliography of Nude Photography Books Published in England from 1896 to 1960. Wolfbait Books. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-916215-11-5.

- ^ Routledge, Isobel (November 28, 2014). "Meditation and modernity: an image of Marguerite Agniel". Wellcome Library.

- ^ a b c Agniel, Marguerite (1931). The Art of the Body : Rhythmic Exercise for Health and Beauty. London: B. T. Batsford. p. ix. OCLC 1069247718.

- ^ Schrank, Sarah (2016). "Naked Yoga and the Sexualization of Asana". In Berila, Beth; Klein, Melanie; Roberts, Chelsea Jackson (eds.). Yoga, the Body, and Embodied Social Change: An Intersectional Feminist Analysis. Lexington Books. pp. 155–174. ISBN 978-1-4985-2803-0.

- ^ Schrank, Sarah (2019). Free and natural: nudity and the American cult of the body. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-8122-5142-5. OCLC 1056781478.

- ^ a b c d "Modern Scottish Women / Painters and Sculptors 1885–1965". Georgina Coburn Arts. January 27, 2016.

- ^ a b Smither, Devon (2019). "Defying convention: The female nude in Canadian painting and photography during the interwar period". Journal of Historical Sociology. 32 (1): 77–93. doi:10.1111/johs.12219. ISSN 0952-1909. S2CID 150507132.

- ^ a b O'Connor, Mary; Tweedie, Katherine (2007). Seduced by Modernity: The Photography of Margaret Watkins. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-7735-7566-0.