Summary

The Meta Romuli (in Latin mēta Rōmulī [ˈmeːta ˈroː.mʊ.ɫ̪iː], transl.: "Pyramid of Romulus"; also named "Piramide vaticana" or "Piramide di Borgo" in Italian) was a pyramid built in ancient Rome that is important for historical, religious and architectural reasons. By the 16th century, it was almost completely demolished.

The Meta Romuli between the Circus Neronis and the Mausoleum of Hadrian in a description of ancient Rome by Pirro Ligorio (1561) | |

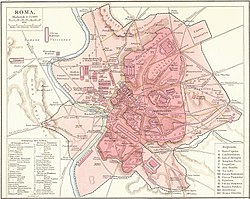

Meta Romuli Shown within Rome | |

| Location | Ager Vaticanus |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°54′09.576″N 12°27′48.960″E / 41.90266000°N 12.46360000°E |

| Type | Pyramid |

| History | |

| Founded | 1st century b.c. or 1st century a.d. |

Location edit

The pyramid was located in today's Borgo district of Rome, between Old Saint Peter's Basilica in the Vatican and the Mausoleum of Hadrian. Its foundations have been discovered under the first north block of via della Conciliazione, which now includes the Auditorium della Conciliazione and the Palazzo Pio.[1]

History edit

The Meta Romuli was a monumental burial erected in the Roman age on the right bank of the Tiber, near the intersection of two Roman roads, the Via Cornelia and the Via Triumphalis, in an area outside the pomerium (the religious boundary around Rome); this area, named Ager Vaticanus, hosted at that time numerous cemetery areas such as the nearby Vatican Necropolis and, due to its proximity to the Campus Martius represented an ideal area to build the monumental tombs of the members of the roman upper class.[2] It was directly south next to another large mausoleum, the so-called Therebintus Neronis,[3] whose demolition started during the 7th century, which had instead a circular plan and the shape of a giant tumulus tomb.[2] While both monuments survived the great changes due to the construction of the old St. Peter's Basilica, the latter was destroyed already during the Middle Ages, while the former survived until the Renaissance age becoming an important element of Rome's topography.[2] It is clear that the man who could afford to build such a monument could only have been a prominent figure of the Roman state, but his name remains unknown.[4]

The first mention of the Meta can be found in a comment to Horace by the Pseudo-Acron (a writer of the 5th century AD)[5] who mentions that the ashes of Scipio Africanus were taken from a pyramid in the Vatican; due to that, the Meta Romuli was also named "Sepulcher of the Scipions".[6]

The name Meta Romuli instead was due to a popular belief, which linked it to the pyramid of Cestius (named Meta Remi in the Middle Ages and lying near the Basilica of Saint Paul), identifying them with the tombs of Romulus and Remus, the two mythical founders of Rome, and making them the object of various legends, based upon the analogy between the founders of the city and the apostles Peter and Paul.[6] It was traditionally believed that the site of the martyrdom of Saint Peter, described as ad Therebintum inter duas metas...in Vaticano, was placed either between the Therebintus and the Meta Romuli, or between the latter and the obelisk of the Circus of Nero, or - in a larger context - in the mid-point between the Meta Romuli and the pyramid of Cestius, that is the place on the Janiculum hill called Montorio, where in the Renaissance Donato Bramante built the Tempietto di San Pietro;[6] consequently, the pyramid was represented for centuries in the depictions of St. Peter's martyrdom.[6] The tomb had also a great importance for the pilgrims who reach Saint Peter, since on their way to the Basilica they met the tomb of the founder of the city before that of the founder of the church.[6]

Due to that, the Meta Romuli was a popular subject in the representations of the city in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Some examples are the Stefaneschi Polyptych by Giotto; a polyptych by Jacopo di Cione; one tile of Filarete's Bronze Doors in Old St. Peter's Basilica; the fresco of The Vision of the Cross in Raphael's Rooms in the Vatican; and the frescoes on the vaults of the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi by Cimabue.[6][7]

The cella of the pyramid was used for centuries as a granary by the Chapter of Saint Peter, which owned it from the 13th century until its destruction.[8] At the beginning of the 15th century, the pyramid's pinnacle was demolished; on the platform which resulted were garrisoned soldiers of the nearby Castle, who got their supplies thorough a system of ropes hanging to the fortress.[8]

Despite its importance for the city and for the church, Pope Alexander VI ordered its demolition on 26 November 1498[7] for the opening of the new Via Alessandrina (later known as Borgo Nuovo), a road which connected the Vatican area with the bridge crossing the Tiber.[7] Due to the difficulty of the undertaking, the pope conceded a plenary indulgence to the men willing to help.[4] On 24 December 1499, the pope blocked all the old roads between Saint Peter and the Tiber, forcing the people to use the new thoroughfare; however, the demolition of the pyramid was not complete, since Raphael, who arrived in Rome in 1509, in a letter to Pope Leo X written in 1519 about the antiquities of the city, writes that he could still see the remains of the monument.[4] In 1511, Pope Julius II claimed ownership of the monument, and in several documents of the 16th century until 1568 the Meta was cited as the end of the Palio race.[9]

Structure edit

The adoption of the pyramidal shape for sepulchral monuments was popular during the Augustan period, in the context of cultural influences from Egypt.[10] Many pyramidal tombs were built, between 40 and 50 meters high, of which only that of Gaius Cestius survives.

The Vatican pyramid dated back presumably to the same age or to the first imperial age,[11] and according to evidence was larger than the Cestia pyramid; as per 15th-century accounts, it had a square plan with sides 25 metres (82 ft) long and was between 32 and 50 meters high.[7] The Mirabilia Urbis Romae (a 12th-century guide of the city) says that the monument fuit miro lapide tabulata ("was sided with wonderful stone") [12] and that pope Donus (r. 676–8) dismantled its siding to pave the quadriporticus and the stairs of Saint Peter's church.[7][4][13] The construction was very robust: Michele Ferno, an eyewitness of the demolition, could visit the burial chamber, which was reachable through a long tunnel; its walls had four niches to keep the defuncts' ashes,[13] and with a side of 7 m and a height of 10.5 m [13] it was almost as big as that of the Mausoleum of Hadrian (which has a side of 7.8 m and a height of 10–12 m).[4] Ferno writes also that during its demolition, which took place between April and 24 December 1499, the concrete of the building was so hard that it had to be demolished with a trip hammer; the bangs which resulted were so loud like those produced by beating a mountain of iron.[4]

In 1948–49, during the works for the construction of the first block of the north side of Via della Conciliazione, it came to light a northwest–southeast-oriented foundation[3] of concrete conglomeration made by tufa quarry waste, surrounded by a large pavement made with travertine slabs.[1] These remains fully confirm the description of the Meta found in the Mirabilia and those given by the eyewitnesses.[1]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c Petacco (2016) p. 37

- ^ a b c Petacco (2016), p. 33

- ^ a b Coarelli (1974) p. 322

- ^ a b c d e f Petacco (2016) p. 36

- ^ Ps. - Acro, in Hor. Epod. 9, 25

- ^ a b c d e f Petacco (2016), p. 34

- ^ a b c d e Petacco (2016), p. 35

- ^ a b Gigli (1990) p. 84

- ^ Castagnoli, (1958), p. 363

- ^ "Pyramid of Gaius Cestius". Rome Reborn - University of Virginia. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Castagnoli, (1958), p. 229

- ^ Mirabilia, 20, 3, 1-4

- ^ a b c Gigli (1990) p. 82

Sources edit

- Castagnoli, Ferdinando; Cecchelli, Carlo; Giovannoni, Gustavo; Zocca, Mario (1958). Topografia e urbanistica di Roma (in Italian). Bologna: Cappelli.

- Coarelli, Filippo (1974). Guida archeologica di Roma (in Italian). Milano: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore.

- Gigli, Laura (1990). Guide rionali di Roma (in Italian). Vol. Borgo (I). Roma: Fratelli Palombi Editori. ISSN 0393-2710.

- Petacco, Laura (2016). Claudio Parisi Presicce; Laura Petacco (eds.). La Meta Romuli e il Therebintus Neronis (in Italian). Rome: Gangemi. ISBN 978-88-492-3320-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)