Summary

Mount Harriet National Park, officially renamed as Mount Manipur National Park, is a national park located in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands union territory of India.[1] The park, established in 1969, covers about 4.62 km2 (18.00 mi2).[2] Mount Manipur (Mount Harriet) (383 metres (1,257 ft)[3]), which is a part of the park, is the third-highest peak in the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago next to Saddle Peak (732 metres (2,402 ft)) in North Andaman and Mount Thullier (568 metres (1,864 ft)) in Great Nicobar.[4]

| Mount Harriet National Park (Mount Manipur National Park) | |

|---|---|

Centaur oakblue at Mt. Harriet National Park | |

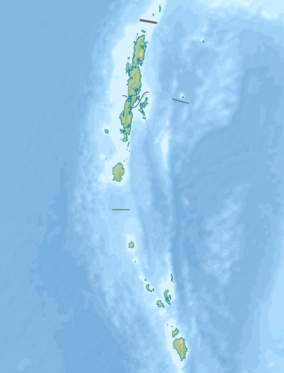

Location in Andaman and Nicobar Islands  Mount Harriet National Park (India) | |

| Location | Ferrargunj tehsil |

| Nearest city | Port Blair |

| Coordinates | 11°42′59″N 92°44′02″E / 11.71639°N 92.73389°E |

| Area | 46.62 square kilometres (18.00 sq mi) |

| Established | 1979 |

| Governing body | Government of India |

The park is named in commemoration of Harriet C. Tytler, the second wife of Robert Christopher Tytler, a British army officer, an administrator, naturalist and photographer, who was appointed Superintendent of the Convict Settlement at Port Blair in the Andamans from April 1862 to February 1864.[5] Harriet is remembered for her work in documenting the monuments of Delhi and for her notes at the time of the Revolt of 1857 in India.[6]

The park's well-known faunal species are Andaman wild pigs (an endangered species), saltwater crocodiles, turtles and robber crabs.[7] The park is also a butterfly hotspot.[3] The picture on the back side of ₹ 20 banknote has been taken at the park.[citation needed]

Geography edit

Mount Harriet National Park was originally a reserve forest which was converted into a national park in 1979. It encompasses an area of 4,662 hectares (11,520 acres), which is likely to be extended to cover an additional area of 1,700 hectares (4,200 acres)[8] to include adjoining mountain ranges and the marine ecosystem on the eastern coast. The mountains in the park are aligned in a north–south direction with the ridges and spurs originating from it aligned in an east–west direction. The park's elevation range is from zero at the coast to the peak level of 481 metres (1,578 ft).[8] The eastern face of the park has steep slopes, and the beaches here are also formed of rocks interspersed with small sandy areas. The park is drained by many streams which rise in the hills and flow into the sea on the east.[8] The park experiences marine climatic conditions,[2] and hot and humid conditions in view of its proximity to the equator.[8]

A notable feature 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) away from the park is Kalapathar, where prisoners used to be pushed down the ravine to their death.[3]

The park is at a distance of 20 kilometres (12 mi) from Port Blair, the capital of the union territory, which also has an airport.

Trekking through the park is popular as it passes through an attractive beach; one can watch endemic avifauna, animals, and butterflies that fly around, and also see elephants carrying lumber.[9]

The tribal community living in the tropical forest of the park are the Negrito people, who are hunter-gatherers.[7]

Flora edit

The park has evergreen primary forests, and at Chiriyatapu the forest type is mixed deciduous, a combination of primary and secondary forests.[10] The three types of forests are categorized as tropical evergreen, hilltop tropical evergreen and littoral. Overall 134 plant and tree species are reported, including 74 native and 51 introduced species.[8] Some of the plant species of the tropical variety are:Dipterocarpus gracilis, Dipterocarpus grandiflorus, Dipterocarpus kerrii, Endospermum chinensis, and Hopea odorata including Araucaria columnaris which is a conifer native to Caledonia Islands. Plant species of the hilltop tropical variety are Canarium manii, Cratoxylum formosum, and Dipterocarpus costatus. The littoral forest species are mainly Manilkara littoralis and Moringa citrifolia.[9]

Trekking along the 7-kilometre (4.3 mi) path from Bambooflat to the mountain top at 365 metres (1,198 ft), trees are seen with hanging vines.[11]

Fauna edit

Avifauna identified by Bird Life International include seven 'near threatened' species which are: the Andaman wood pigeon (Columba palumboides), Andaman cuckoo-dove (Macropygia rufipennis), Andaman scops-owl (Otus balli), Andaman boobook (Ninox affinis), Andaman woodpecker (Dryocopus hodgei), Andaman drongo (Dicrurus andamanensis), and Andaman treepie (Dendrocitta bayleyi); there are also two species of 'least concern', which are the Andaman coucal (Centropus andamanensis) and white-headed starling (Sturnus erythropygius).[8]

Introduced species include the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) and chital (Axis axis) apart from ferals. There are 28 reptile species recorded (including 14 species endemic to the Andamans) which are mostly lizards and snakes. The amphibian fauna reported are 6 species; 2 species of Andaman bull frog (Kaloula baleata ghoshi) and Andaman paddy field frog (Limnonectes andamanensis) are endemic.[8]

The aquatic fauna reported from the streams consist of 16 species; some of these species are eel, catfish, gobies, sleepers and snakeheads.[8]

The land molluscs consist of six species. The invertebrate species reported are 355 which include insects to the extent of 70%.[8] The well-known insect silkmoth, Samia cynthia, has been recorded in the park in lowland forest areas up to 365 metres (1,198 ft). In addition, larvae of Samia fulva were noted eating the leaves of Zanthoxylum rhetsa (Rutaceae) and Heteropanax fragrans (Araliaceae). [10]

References edit

- ^ "Celebrations in Manipur for renaming Andman's Mount Harriet Park". www.daijiworld.com. Retrieved 2021-10-18.

- ^ a b Negi 2002, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Outlook 2008, p. 38.

- ^ Venkataraman, Raghunathan & Sivaperuman 2012, p. 7.

- ^ "Robert Christopher Tytler". britishempire.co.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Dalrymple 2009, p. 443.

- ^ a b Husain, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Mount Harriet National Park". Bird Life International. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ a b Negi 1993, p. 189.

- ^ a b Peigler & Naumann 2003, p. 131.

- ^ Abram & Edwards 2003, p. 589.

Bibliography edit

- Abram, David; Edwards, Nick (2003). South India. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-103-6.

- Dalrymple, William (17 August 2009). The Last Mughal: The Fall of Delhi, 1857. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4088-0688-3.

- Husain, Majid. Understanding Geographical Map Entries. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-009099-6.

- Negi, Sharad Singh (1 January 1993). Biodiversity and Its Conservation in India. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-85182-88-9.

- Negi, Sharad Singh (2002). Handbook of National Parks, Wildlife Sanctuaries, and Biosphere Reserves in India. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-128-3.

- Peigler, Richard Steven; Naumann, Stefan (2003). A revision of the silkmoth genus Samia. University of the Incarnate Word. ISBN 978-0-9728266-0-0.

- Outlook Traveller. Outlook Publishing. January 2008.

- Venkataraman, K.; Raghunathan, C.; Sivaperuman, C. (2 June 2012). Ecology of Faunal Communities on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-28335-2.