Summary

Sir Charles Norman Lockhart Stronge, 8th Baronet, MC, PC, JP (23 July 1894 – 21 January 1981) was a senior Ulster Unionist Party politician in Northern Ireland.

Norman Stronge | |

|---|---|

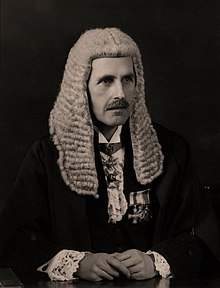

Sir Norman Stronge wearing the Speaker's wig. | |

| Speaker of the Northern Ireland House of Commons | |

| In office 1945–1956 | |

| In office 1956–1969 | |

| Member of the Northern Ireland House of Commons | |

| In office 1938–1969 | |

| Constituency | Mid Armagh |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Charles Norman Lockhart Stronge 23 July 1894 Bryansford, County Down, Ireland |

| Died | 21 January 1981 (aged 86) Tynan Abbey, County Armagh, Northern Ireland |

| Manner of death | Assassination (gunshot wounds) |

| Political party | Ulster Unionist Party |

| Spouse(s) | Gladys Olive Hall (born 23 July 1894; m. 1921–1980; her death); 4 children |

| Children | James Stronge Daphne Marian, Mrs Kingan Evelyn Elizabeth Stronge Rosemary Diana Stronge |

Before his involvement in politics, he fought in the First World War as a junior officer in the British Army. He fought in the Battle of the Somme in 1916 and was awarded the Military Cross. His positions after the war included Speaker of the House of Commons of Northern Ireland for twenty-three years.

He was shot and killed[1] (aged 86), along with his son, James (aged 48), by the Provisional Irish Republican Army in 1981 at Tynan Abbey, their home, which was burnt to the ground during the attack.

Early life and military service edit

Charles Norman Lockhart Stronge was born in Bryansford, County Down, Ireland, the son of Sir Charles Stronge, 7th Baronet, and Marian Bostock, whose family were from Epsom.[2]

Educated at Eton, during the First World War (1914–18) he joined the British Army and was commissioned as a second lieutenant into the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. He fought on the Western Front with the 10th (Service) Battalion, as lieutenant and later as captain.[3] He was decorated with the Military Cross[4] and the Belgian croix de guerre. He survived the first day of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916 and was the first soldier after the start of the battle to be mentioned in dispatches by General Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front. In April 1918, he was appointed adjutant of the 15th (Service) Battalion (North Belfast), Royal Irish Rifles.[5] He was wounded in action near Kortrijk, Belgium towards the end of the war on 20 October 1918.[6] He relinquished his commission on 19 August 1919, and was permitted to retain the rank of captain.[7]

On the outbreak of the Second World War (1939–45) in September 1939, he was again commissioned, this time into the North Irish Horse, Royal Armoured Corps, reverting to the rank of second lieutenant.[8] He relinquished the commission on 20 April 1940 due to ill health.[9] In 1950, he was appointed Honorary Colonel of a Territorial Army (TA) unit of the Royal Irish Fusiliers.[10]

Political career edit

Stronge was appointed High Sheriff of County Londonderry in January 1934.[11] He was elected as an Ulster Unionist Party member of the House of Commons of Northern Ireland for Mid Armagh in the byelection of 29 September 1938,[12][13] and held the seat until his retirement in 1969.[14][15][16][17][18][19] He made his maiden speech on 20 October, supporting the Marketing of Potatoes Bill.[20]

In his career at Stormont, he became Assistant Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Finance (Assistant Whip) from 16 January 1941;[21] on 6 February 1942 he was promoted to be Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Finance (Chief Whip).[22] He held this post at the time when J. M. Andrews was deposed as Prime Minister of Northern Ireland and replaced by Sir Basil Brooke due to backbench pressure from Ulster Unionist MPs. On 3 November 1944, Stronge stood down from the government.[citation needed]

When the new Parliament assembled on 17 July 1945 Stronge was nominated as Speaker of the Northern Ireland House of Commons by Lord Glentoran, who said that Stronge came from a "family which has been known for generations for its fairness, its courtesy, and its neighbourliness, and for that feeling of kindliness which is so essential to the Speaker of this House".[23] The nomination was seconded by Jack Beattie, an Irish nationalist who sat as an Independent Labour MP.

On 30 October 1945, Stronge was involved in a dispute in the chamber. A minister in the government had been taken ill and was unable to answer a series of Parliamentary Questions which had been put to him; Stronge allowed the Members who had put the questions to defer them until the Minister had recovered.[24] Beattie protested that this was not correct procedure, and Stronge agreed to look at it further; this decision incensed Harry Midgley, who had personal grievances with Beattie. Midgley shouted at Stronge "Are you not competent to discharge your duties without advice from this Member on his weekly visits to the House?" Despite Stronge calling for order, Midgley then crossed over and punched Beattie. Stronge excluded him from the Chamber for the remainder of the sitting,[25] and Midgley apologised the next day.[26]

Stronge was appointed to the Privy Council of Northern Ireland in 1946.[27][28][29] He was Chairman of Armagh County Council[30] from 1944 to 1955. Among other positions he held were Lord Lieutenant of Armagh (1939–81),[31][32] (he was a Deputy Lieutenant from 1931[33][34]) President of the Northern Ireland Council of the Royal British Legion and Justice of the Peace for both Counties Armagh and Londonderry. He was the Sovereign Grand Master of the Royal Black Institution and a member of Derryshaw Boyne Defenders Orange Lodge of the Orange Order. Stronge was appointed a Commander Brother of the Venerable Order of Saint John in 1952,[35] and promoted to Knight in 1964.[36]

In 1956, one of Stronge's outside posts caused difficulty. He had been named on the Central Advisory Council on Disabled Persons, a position which brought no remuneration in practice but could have done so in theory. It was realised that the theoretical possibility of money being paid meant that this was an "Office of Profit under the Crown" which disqualified him from election. On 16 January 1956 Stronge wrote to resign his post as Speaker temporarily so that legislation could be passed to validate his actions and indemnify him from the consequences of acting while disqualified.[37] Owing to the constitutional provisions of the Government of Ireland Act, this legislation had to be passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom.[citation needed]

Once it had been passed, on 23 April 1956 the Speaker who had been elected temporarily (W. F. McCoy) resigned.[38] Stronge was re-elected on 26 April, referring in his speech accepting the nomination to his time away from Parliament looking after his farm: "I have had more time to look at bullocks, and more time to look at their prices".[39]

Family edit

Stronge was married on 15 September 1921 to Gladys Olive Hall,[40] daughter of Major H. T. Hall,[2] originally from Athenry, County Galway.[2][41] The couple had four children:

- James Stronge (who was killed with him),

- Daphne Marian Stronge (1922–2002,[42] married Thomas John Anthony Kingan, of Bangor, County Down, on 11 December 1954. Her son, James, and his family, now own the family's property in Tynan;[42] he was a UUP candidate for North Down Council[42]),[40]

- Evelyn Elizabeth "Evie" Stronge (born 1925; married Brigadier Charles Harold Arthur Olivier on 17 September 1960),[40]

- Rosemary Diana Stronge (1928–1929; died at age one).[40]

After Stronge's retirement from politics in 1969, he farmed the family's several thousand acre estate at Tynan Abbey.[43]

Death edit

Sir Norman Stronge (aged 86) and his son, James (aged 48), were killed while watching television in the library of their home,[42] Tynan Abbey, on the evening of 21 January 1981, by members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), armed with machine guns, who used grenades to break down the locked heavy doors to the home.[42]

The Stronge family home was then burnt to the ground as a result of two bomb explosions.[44] On seeing the explosions at the house (and a flare Stronge lit in an attempt to alert the authorities), the Royal Ulster Constabulary and British Army troops arrived at the scene and established a road-block at the gate lodge. They encountered at least eight fleeing gunmen in two cars. An RUC officer said afterwards that they at first mistook the IRA men, wearing black berets and "combat gear", for members of the British Army's Special Air Service (SAS).[45] There followed a gunfight lasting twenty minutes in which at least two hundred shots were fired. There were no casualties among the security forces but the gunmen escaped.[6] The bodies of the father and son were later discovered in the library of their blazing home, each had gunshot wounds in the head.[44]

Stronge was buried in Tynan Parish church in a joint service with his son. The sword and cap of the Lord Lieutenant of Tyrone (Major John Hamilton-Stubber) were placed on his coffin in lieu of his own, which had been destroyed with his other possessions in the fire.[6]

The coffin was carried by the 5th Battalion the Royal Irish Rangers, the successors to his old regiment. During the service, a telegram, sent from Queen Elizabeth II to one of Sir Norman's daughters, was read. It stated:[46]

I was deeply shocked to learn of the tragic death of your father and brother; Prince Philip joins me in sending you and your sister all our deepest sympathy on your dreadful loss. Sir Norman's loyal and distinguished service will be remembered.

The funeral was described in the following words:

The village of Tynan was crowded for the double funeral of Sir Norman Stronge and his son James. Mourners came from throughout the province and from England, including lords, politicians, policemen, judges and church leaders. The remains of Sir Norman were carried by the men of the 5th Battalion the Royal Irish Rangers. On the coffin were the cap and sword of Major John Hamilton-Stubber, Lord Lieutenant for County Tyrone, for all Sir Norman's possessions were destroyed in the fire which gutted the Abbey. James Stronge's coffin was carried by colleagues from the RUC Reserve, and a Constable's hat was placed on top. The coffins were met by the Rector of Tynan, former RAF Chaplain the Rev Tom Taylor, a close friend of the family. Two Royal British Legion standards were carried into the church. Sir Norman's daughters Daphne and Evie were accompanied by their husbands, and his grandson Mr James Kingan was also present. The funeral service was relayed over an amplifying system, as the church could only accommodate a small proportion of the mourners. After the service, the chief mourners moved out into the churchyard where the Last Post was sounded and a Royal British Legion farewell was given. The two coffins were laid in the family plot, where Lady Stronge, Sir Norman's wife and mother of James, was buried a year previously.[47]

The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Humphrey Atkins, was informed by friends of the Stronge family that he would not be welcome at the funeral because of government policy on Irish border security.[48] Atkins left the Northern Ireland Office later that year, to be replaced by Jim Prior.

Stronge is commemorated with a tablet in the Northern Ireland Assembly Chamber (the former House of Commons Chamber) in Parliament Buildings on the Stormont Estate.[49]

Reactions edit

The IRA released a statement in Belfast, quoted in The Times, claiming that "This deliberate attack on the symbols of hated unionism was a direct reprisal for a whole series of loyalist assassinations and murder attacks on nationalist peoples and nationalist activities." This followed the loyalist attempted killing of Bernadette McAliskey and her husband Michael McAliskey on 16 January, and the loyalist assassinations of four republican activists which had taken place since May 1980 (Miriam Daly, John Turnley, Noel Lyttle and Ronnie Bunting).[50]

The killings were referred to as murder by multiple media sources including The Daily Telegraph, The Scotsman, The New York Times and Time magazine, by the Reverend Ian Paisley in the House of Commons and by Lord Cooke of Islandreagh in the House of Lords.[51]

Stronge was described at the time of his death by Social Democratic and Labour Party politician Austin Currie as having been "even at 86 years of age … still incomparably more of a man than the cowardly dregs of humanity who ended his life in this barbaric way".[52]

Later events edit

In 1984, Seamus Shannon was arrested by the Garda in the Republic of Ireland and handed over to the Royal Ulster Constabulary on a warrant accusing him of involvement in the murders of Sir Norman Stronge and Sir James Stronge. The Irish Supreme Court, considering his extradition to Northern Ireland, rejected the defence that these were political offences, saying that they were "so brutal, cowardly and callous that it would be a distortion of language if they were to be accorded the status of a political offence". Shannon was extradited but later acquitted.[53][54]

In 2015, Mitchel McLaughlin MLA was elected Speaker of the Northern Ireland Assembly. McLaughlin was the first Speaker elected from Sinn Féin whose leader, Gerry Adams, had said regarding the Stronge murders: "The only complaint I have heard from nationalists or anti-unionists is that he was not shot 40 years ago."[55]

Speaking during the debate on McLaughlin's election, Traditional Unionist Voice politician Jim Allister criticised the Democratic Unionist Party MLAs for voting to help elect McLaughlin as Speaker. He said "the next time they walk past the memorial to Sir Norman Stronge, may they hang their heads in shame."[56]

Further reading edit

- Burke's Peerage & Baronetage. 1975.

Notes and references edit

- ^ Tim Pat Coogan, The IRA; ISBN 0-00-636943-X, chapter 33.

- ^ a b c 'STRONGE, Captain Rt. Hon. Sir (Charles) Norman (Lockhart)’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007 Profile, ukwhoswho.com; accessed 4 December 2010.

- ^ "No. 29820". The London Gazette (Supplement). 10 November 1916. p. 10945.

- ^ "No. 30450". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 December 1917. pp. 30–47.

- ^ "No. 30850". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 August 1918. p. 9669.

- ^ a b c Stronge of Tynan Abbey, County Armagh, turtlebunbury.com; accessed 3 November 2015.

- ^ "No. 31612". The London Gazette (Supplement). 21 October 1919. p. 12974.

- ^ "No. 34704". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 October 1939. p. 6787.

- ^ "No. 34832". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 April 1940. p. 2303.

- ^ "No. 39102". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 December 1950. p. 6467.

- ^ "No. 656". The Belfast Gazette. 19 January 1934. p. 21.

- ^ "No. 902". The Belfast Gazette. 7 October 1938. p. 343.

- ^ "Mid Armagh election results". Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ^ "No. 1256". The Belfast Gazette. 20 July 1945. p. 163.

- ^ "No. 1445". The Belfast Gazette. 4 March 1949. p. 48.

- ^ "No. 1689". The Belfast Gazette. 6 November 1953. p. 270.

- ^ "No. 1919". The Belfast Gazette. 4 April 1958. p. 98.

- ^ "No. 216". The Belfast Gazette. 15 June 1962. p. 226.

- ^ "No. 2334". The Belfast Gazette. 3 December 1965. p. 427.

- ^ Hansard, House of Commons of Northern Ireland, Vol. 21, Col. 1778, via Stormont Papers.

- ^ "No. 1021". The Belfast Gazette. 17 January 1941. p. 17.

- ^ "No. 1076". The Belfast Gazette. 6 February 1942. p. 33.

- ^ Hansard, House of Commons of Northern Ireland, Vol. 29, col. 3, via Stormont Papers.

- ^ Hansard, House of Commons of Northern Ireland, Vol. 29, Col. 896, via Stormont Papers.

- ^ Hansard, House of Commons of Northern Ireland, Vol. 29, cols. 910-11, via Stormont Papers.

- ^ Hansard, House of Commons of Northern Ireland, Vol. 29, col. 952, via Stormont Papers.

- ^ "No. 1280". The Belfast Gazette. 4 January 1946. p. 1.

- ^ "No. 1289". The Belfast Gazette. 8 March 1946. p. 59.

- ^ "Biographies of Members of the Northern Ireland House of Commons". Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- ^ "No. 1308". The Belfast Gazette. 19 July 1946. pp. 174–175.

- ^ "No. 963". The Belfast Gazette. 8 December 1939. p. 399.

- ^ "No. 3164". The Belfast Gazette. 27 June 1975. p. 475.

- ^ "No. 505". The Belfast Gazette. 27 February 1931. p. 171.

- ^ "No. 637". The Belfast Gazette. 8 September 1933. p. 957.

- ^ "No. 39433". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1952. p. 137.

- ^ "No. 43219". The London Gazette (Supplement). 14 January 1964. p. 388.

- ^ Hansard, House of Commons of Northern Ireland, Vol. 39, col. 3141, via Stormont Papers.

- ^ Hansard, House of Commons of Northern Ireland, Vol. 40, Col. 927, via Stormont Papers, stormontpapers.ahds.ac.uk; accessed 3 November 2015.

- ^ Hansard, House of Commons of Northern Ireland, Vol. 40, Col. 931, via Stormont Papers, stormontpapers.ahds.ac.uk; accessed 3 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Stronge family tree

- ^ Turtle Bunbury; Stronge of Tynan Abbey

- ^ a b c d e Turtle Bunbury; Stronge of Tynan Abbey

- ^ genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com; accessed 3 November 2015.

- ^ a b The Times, 22 January 1981.

- ^ The Belfast Telegraph, 22 January 1981.

- ^ Tragic estate resurrected. The News Letter 12 May 2006

- ^ Description of joint funeral, turtlebunbury.com; accessed 3 November 2015.

- ^ Craig Seton (26 January 1981). "Mr Atkins asked not to attend funeral". News. The Times. No. 60835. London. col G, p. 1.

- ^ 'Memorials to the Casualties of Conflict: Northern Ireland 1969 to 1997' by Jane Leonard (1997), cain.ulst.ac.uk; accessed 3 November 2015.

- ^ Christopher Thomas (23 January 1981). "Ex-Speaker killed by IRA as reprisal". News. The Times. No. 60833. London. col F, p. 1.

- ^ *Time (in partnership with CNN), 2 February 1981 [1]

- The New York Times, 30 January 1981 (13th article: "Murders bring fear to Protestants on Ulster border")[2]

- Commons Hansard, Rev. Ian Paisley, 1992-06-10 [3]

- The Spectator, 13 December 1997 [4][dead link]

- Lords Hansard, Lord Cooke of Islandreagh, 22 March 2000 [5]

- The News Letter (Belfast, Northern Ireland), 19 January 2001 [6]

- The Daily Telegraph, 22 November 2001 [7][permanent dead link]

- The Scotsman, 10 April 2006 [8]

- ^ 'In the Shadow of the Gunmen", time.com; accessed 3 November 2015.

- ^ Seanad Éireann – Volume 139 – 24 March 1994. Extradition (Amendment) Bill, 1994: Second Stage Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Oireachtas historical debates

- ^ House of Commons Hansard Debates for 10 June 1992, parliament.uk; accessed 3 November 2015.

- ^ A Secret History of the IRA, Ed Moloney, 2002. (PB) ISBN 0-393-32502-4; (HB) ISBN 0-7139-9665-X, p. 320.

- ^ Official Report: Monday, 12 January 2015, Northern Ireland Assembly, niassembly.gov.uk; accessed 3 November 2015.