Summary

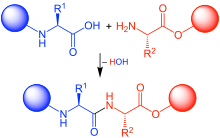

In organic chemistry, peptide synthesis is the production of peptides, compounds where multiple amino acids are linked via amide bonds, also known as peptide bonds. Peptides are chemically synthesized by the condensation reaction of the carboxyl group of one amino acid to the amino group of another. Protecting group strategies are usually necessary to prevent undesirable side reactions with the various amino acid side chains.[1] Chemical peptide synthesis most commonly starts at the carboxyl end of the peptide (C-terminus), and proceeds toward the amino-terminus (N-terminus).[2] Protein biosynthesis (long peptides) in living organisms occurs in the opposite direction.

The chemical synthesis of peptides can be carried out using classical solution-phase techniques, although these have been replaced in most research and development settings by solid-phase methods (see below).[3] Solution-phase synthesis retains its usefulness in large-scale production of peptides for industrial purposes moreover.

Chemical synthesis facilitates the production of peptides that are difficult to express in bacteria, the incorporation of unnatural amino acids, peptide/protein backbone modification, and the synthesis of D-proteins, which consist of D-amino acids.

Solid-phase synthesis edit

The established method for the production of synthetic peptides in the lab is known as solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS).[2] Pioneered by Robert Bruce Merrifield,[4][5] SPPS allows the rapid assembly of a peptide chain through successive reactions of amino acid derivatives on a macroscopically insoluble solvent-swollen beaded resin support.[citation needed]

The solid support consists of small, polymeric resin beads functionalized with reactive groups (such as amine or hydroxyl groups) that link to the nascent peptide chain.[2] Since the peptide remains covalently attached to the support throughout the synthesis, excess reagents and side products can be removed by washing and filtration. This approach circumvents the comparatively time-consuming isolation of the product peptide from solution after each reaction step, which would be required when using conventional solution-phase synthesis.[citation needed]

Each amino acid to be coupled to the peptide chain N-terminus must be protected on its N-terminus and side chain using appropriate protecting groups such as Boc (acid-labile) or Fmoc (base-labile), depending on the side chain and the protection strategy used (see below).[1]

The general SPPS procedure is one of repeated cycles of alternate N-terminal deprotection and coupling reactions. The resin can be washed between each steps.[2] First an amino acid is coupled to the resin. Subsequently, the amine is deprotected, and then coupled with the activated carboxyl group of the next amino acid to be added. This cycle is repeated until the desired sequence has been synthesized. SPPS cycles may also include capping steps which block the ends of unreacted amino acids from reacting. At the end of the synthesis, the crude peptide is cleaved from the solid support while simultaneously removing all protecting groups using a reagent such as trifluoroacetic acid.[2] The crude peptide can be precipitated from a non-polar solvent like diethyl ether in order to remove organic soluble byproducts. The crude peptide can be purified using reversed-phase HPLC.[6][7] The purification process, especially of longer peptides can be challenging, because cumulative amounts of numerous minor byproducts, which have properties similar to the desired peptide product, have to be removed. For this reason so-called continuous chromatography processes such as MCSGP are increasingly being used in commercial settings to maximize the yield without sacrificing purity.[8]

SPPS is limited by reaction yields due to the exponential accumulation of by-products, and typically peptides and proteins in the range of 70 amino acids are pushing the limits of synthetic accessibility.[2] Synthetic difficulty also is sequence dependent; typically aggregation-prone sequences such as amyloids[9] are difficult to make. Longer lengths can be accessed by using ligation approaches such as native chemical ligation, where two shorter fully deprotected synthetic peptides can be joined in solution.

Peptide coupling reagents edit

An important feature that has enabled the broad application of SPPS is the generation of extremely high yields in the coupling step.[2] Highly efficient amide bond-formation conditions are required. To illustrate the impact of suboptimal coupling yields for a given synthesis, consider the case where each coupling step were to have at least 99% yield: this would result in a 77% overall crude yield for a 26-amino acid peptide (assuming 100% yield in each deprotection); if each coupling were 95% efficient, the overall yield would be 25%.[10][11] and adding an excess of each amino acid (between 2- and 10-fold). The minimization of amino acid racemization during coupling is also of vital importance to avoid epimerization in the final peptide product.[citation needed]

Amide bond formation between an amine and carboxylic acid is slow, and as such usually requires 'coupling reagents' or 'activators'. A wide range of coupling reagents exist, due in part to their varying effectiveness for particular couplings,[12][13] many of these reagents are commercially available.

Carbodiimides edit

Carbodiimides such as dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) and diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) are frequently used for amide bond formation.[11] The reaction proceeds via the formation of a highly reactive O-acylisourea. This reactive intermediate is attacked by the peptide N-terminal amine, forming a peptide bond. Formation of the O-acylisourea proceeds fastest in non-polar solvents such as dichloromethane.[14]

DIC is particularly useful for SPPS since as a liquid it is easily dispensed, and the urea byproduct is easily washed away. Conversely, the related carbodiimide 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) is often used for solution-phase peptide couplings as its urea byproduct can be removed by washing during aqueous work-up.[11]

Carbodiimide activation opens the possibility for racemization of the activated amino acid.[11] Racemization can be circumvented with 'racemization suppressing' additives such as the triazoles 1-hydroxy-benzotriazole (HOBt), and 1-hydroxy-7-aza-benzotriazole (HOAt). These reagents attack the O-acylisourea intermediate to form an active ester, which subsequently reacts with the peptide to form the desired peptide bond.[15] Ethyl cyanohydroxyiminoacetate (Oxyma), an additive for carbodiimide coupling, acts as an alternative to HOAt.[16]

Aminium/uronium and phosphonium salts edit

Some coupling reagents omit the carbodiimide completely and incorporate the HOAt/HOBt moiety as an aminium/uronium or phosphonium salt of a non-nucleophilic anion (tetrafluoroborate or hexafluorophosphate).[10] Examples of aminium/uronium reagents include HATU (HOAt), HBTU/TBTU (HOBt) and HCTU (6-ClHOBt). HBTU and TBTU differ only in the choice of anion. Phosphonium reagents include PyBOP (HOBt) and PyAOP (HOAt).[citation needed]

These reagents form the same active ester species as the carbodiimide activation conditions, but differ in the rate of the initial activation step, which is determined by nature of the carbon skeleton of the coupling reagent.[17] Furthermore, aminium/uronium reagents are capable of reacting with the peptide N-terminus to form an inactive guanidino by-product, whereas phosphonium reagents are not.

Propanephosphonic acid anhydride edit

Since late 2000s, propanephosphonic acid anhydride, sold commercially under various names such as "T3P", has become a useful reagent for amide bond formation in commercial applications. It converts the oxygen of the carboxylic acid into a leaving group, whose peptide-coupling byproducts are water-soluble and can be easily washed away. In a performance comparison between propanephosphonic acid anhydride and other peptide coupling reagents for the preparation of a nonapeptide drug, it was found that this reagent was superior to other reagents with regards to yield and low epimerization.[18]

Solid supports edit

Solid supports for peptide synthesis are selected for physical stability, to permit the rapid filtration of liquids. Suitable supports are inert to reagents and solvents used during SPPS and allow for the attachment of the first amino acid.[19] Swelling is of great importance because peptide synthesis takes place inside the swollen pores of the solid support.[20]

Three primary types of solid supports are: gel-type supports, surface-type supports, and composites.[19] Improvements to solid supports used for peptide synthesis enhance their ability to withstand the repeated use of TFA during the deprotection step of SPPS.[21] Two primary resins are used, based on whether a C-terminal carboxylic acid or amide is desired. The Wang resin was, as of 1996[update], the most commonly used resin for peptides with C-terminal carboxylic acids.[22][needs update]

Protecting groups schemes edit

As described above, the use of N-terminal and side chain protecting groups is essential during peptide synthesis to avoid undesirable side reactions, such as self-coupling of the activated amino acid leading to (polymerization).[1] This would compete with the intended peptide coupling reaction, resulting in low yield or even complete failure to synthesize the desired peptide.[citation needed]

Two principle protecting group schemes are typically used in solid phase peptide synthesis: so-called Boc/benzyl and Fmoc/tert-butyl approaches.[2] The Boc/Bzl strategy utilizes TFA-labile N-terminal Boc protection alongside side chain protection that is removed using anhydrous hydrogen fluoride during the final cleavage step (with simultaneous cleavage of the peptide from the solid support). Fmoc/tBu SPPS uses base-labile Fmoc N-terminal protection, with side chain protection and a resin linkage that are acid-labile (final acidic cleavage is carried out via TFA treatment).

Both approaches, including the advantages and disadvantages of each, are outlined in more detail below.

Boc/Bzl SPPS edit

Before the advent of SPPS, solution methods for chemical peptide synthesis relied on tert-butyloxycarbonyl (abbreviated 'Boc') as a temporary N-terminal α-amino protecting group. The Boc group is removed with acid, such as trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). This forms a positively charged amino group in the presence of excess TFA (note that the amino group is not protonated in the image on the right), which is neutralized and coupled to the incoming activated amino acid.[23] Neutralization can either occur prior to coupling or in situ during the basic coupling reaction.

The Boc/Bzl approach retains its usefulness in reducing peptide aggregation during synthesis.[24] In addition, Boc/benzyl SPPS may be preferred over the Fmoc/tert-butyl approach when synthesizing peptides containing base-sensitive moieties (such as depsipeptides or thioester moeities), as treatment with base is required during the Fmoc deprotection step (see below).

Permanent side-chain protecting groups used during Boc/benzyl SPPS are typically benzyl or benzyl-based groups.[1] Final removal of the peptide from the solid support occurs simultaneously with side chain deprotection using anhydrous hydrogen fluoride via hydrolytic cleavage. The final product is a fluoride salt which is relatively easy to solubilize. Scavengers such as cresol must be added to the HF in order to prevent reactive cations from generating undesired byproducts.

Fmoc/tBu SPPS edit

The use of N-terminal Fmoc protection allows for a milder deprotection scheme than used for Boc/Bzl SPPS, and this protection scheme is truly orthogonal under SPPS conditions.[26] Fmoc deprotection utilizes a base, typically 20–50% piperidine in DMF.[19] The exposed amine is therefore neutral, and consequently no neutralization of the peptide-resin is required, as in the case of the Boc/Bzl approach. The lack of electrostatic repulsion between the peptide chains can lead to increased risk of aggregation with Fmoc/tBu SPPS however. Because the liberated fluorenyl group is a chromophore, Fmoc deprotection can be monitored by UV absorbance of the reaction mixture, a strategy which is employed in automated peptide synthesizers.

The ability of the Fmoc group to be cleaved under relatively mild basic conditions while being stable to acid allows the use of side chain protecting groups such as Boc and tBu that can be removed in milder acidic final cleavage conditions (TFA) than those used for final cleavage in Boc/Bzl SPPS (HF). Scavengers such as water and triisopropylsilane (TIPS) are most commonly added during the final cleavage in order to prevent side reactions with reactive cationic species released as a result of side chain deprotection. Nevertheless, many other scavenger compounds could be used as well.[27][28][29] The resulting crude peptide is obtained as a TFA salt, which is potentially more difficult to solubilize than the fluoride salts generated in Boc SPPS.

Fmoc/tBu SPPS is less atom-economical, as the fluorenyl group is much larger than the Boc group. Accordingly, prices for Fmoc amino acids were high until the large-scale piloting of one of the first synthesized peptide drugs, enfuvirtide, began in the 1990s, when market demand adjusted the relative prices of Fmoc- vs Boc- amino acids.

Other protecting groups edit

Benzyloxy-carbonyl edit

The (Z) group is another carbamate-type amine protecting group, discovered by Leonidas Zervas in the early 1930s and usually added via reaction with benzyl chloroformate.[30]

It is removed under harsh conditions using HBr in acetic acid, or milder conditions of catalytic hydrogenation.

This methodology was first used in the synthesis of oligopeptides by Zervas and Max Bergmann in 1932.[31] Hence, this became known as the Bergmann-Zervas synthesis, which was characterised "epoch-making" and helped establish synthetic peptide chemistry as a distinct field.[30] It constituted the first useful lab method for controlled peptide synthesis, enabling the synthesis of previously unattainable peptides with reactive side-chains, while Z-protected amino acids are also prevented form undergoing racemization.[30][31]

The use of the Bergmann-Zervas method remained the standard practice in peptide chemistry for two full decades after its publication, superseded by newer methods (such as the Boc protecting group) in the early 1950s.[30] Nowadays, while it has been used periodically for α-amine protection, it is much more commonly used for side chain protection.

Alloc and miscellaneous groups edit

The allyloxycarbonyl (alloc) protecting group is sometimes used to protect an amino group (or carboxylic acid or alcohol group) when an orthogonal deprotection scheme is required. It is also sometimes used when conducting on-resin cyclic peptide formation, where the peptide is linked to the resin by a side-chain functional group. The Alloc group can be removed using tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0).[32]

For special applications like synthetic steps involving protein microarrays, protecting groups sometimes termed "lithographic" are used, which are amenable to photochemistry at a particular wavelength of light, and so which can be removed during lithographic types of operations.[33][34][35][36]

Regioselective disulfide bond formation edit

The formation of multiple native disulfides remains challenging of native peptide synthesis by solid-phase methods. Random chain combination typically results in several products with nonnative disulfide bonds.[37] Stepwise formation of disulfide bonds is typically the preferred method, and performed with thiol protecting groups.[38] Different thiol protecting groups provide multiple dimensions of orthogonal protection. These orthogonally protected cysteines are incorporated during the solid-phase synthesis of the peptide. Successive removal of these groups, to allow for selective exposure of free thiol groups, leads to disulfide formation in a stepwise manner. The order of removal of the groups must be considered so that only one group is removed at a time.

Thiol protecting groups used in peptide synthesis requiring later regioselective disulfide bond formation must possess multiple characteristics.[39][40] First, they must be reversible with conditions that do not affect the unprotected side chains. Second, the protecting group must be able to withstand the conditions of solid-phase synthesis. Third, the removal of the thiol protecting group must be such that it leaves intact other thiol protecting groups, if orthogonal protection is desired. That is, the removal of PG A should not affect PG B. Some of the thiol protecting groups commonly used include the acetamidomethyl (Acm), tert-butyl (But), 3-nitro-2-pyridine sulfenyl (NPYS), 2-pyridine-sulfenyl (Pyr), and trityl (Trt) groups.[39] Importantly, the NPYS group can replace the Acm PG to yield an activated thiol.[41]

Using this method, Kiso and coworkers reported the first total synthesis of insulin in 1993.[42] In this work, the A-chain of insulin was prepared with following protecting groups in place on its cysteines: CysA6(But), CysA7(Acm), and CysA11(But), leaving CysA20 unprotected.[42]

Microwave-assisted peptide synthesis edit

Microwave-assisted peptide synthesis has been used to complete long peptide sequences with high degrees of yield and low degrees of racemization.[43][44]

Continuous flow solid-phase peptide synthesis edit

The first article relating to continuous flow peptide synthesis was published in 1986,[45] but due to technical limitations, it was not until the early 2010's when more academic groups started using continuous flow for the rapid synthesis of peptides.[46][47] The advantages of continuous flow over traditional batch methods is the ability to heat reagents with good temperature control, allowing the speed of reaction kinetics while minimising side reactions.[48] cycles times vary from 30 seconds, up to 6 minutes, depending on reaction conditions and excess of reagent.

Thanks to inline analytics, such as UV/Vis spectroscopy and the use of Variable Bed Flow reactor (VBFR) that monitor the resin volume, on-resin aggregation can be identified and coupling efficiency can be evaluated.[49]

Synthesizing long peptides edit

Stepwise elongation, in which the amino acids are connected step-by-step in turn, is ideal for small peptides containing between 2 and 100 amino acid residues. Another method is fragment condensation, in which peptide fragments are coupled.[50][51][52] Although the former can elongate the peptide chain without racemization, the yield drops if only it is used in the creation of long or highly polar peptides. Fragment condensation is better than stepwise elongation for synthesizing sophisticated long peptides, but its use must be restricted in order to protect against racemization. Fragment condensation is also undesirable since the coupled fragment must be in gross excess, which may be a limitation depending on the length of the fragment.[53]

A new development for producing longer peptide chains is chemical ligation: unprotected peptide chains react chemoselectively in aqueous solution. A first kinetically controlled product rearranges to form the amide bond. The most common form of native chemical ligation uses a peptide thioester that reacts with a terminal cysteine residue.[54]

Other methods applicable for covalently linking polypeptides in aqueous solution include the use of split inteins,[55] spontaneous isopeptide bond formation[56] and sortase ligation.[57]

In order to optimize synthesis of long peptides, a method was developed in Medicon Valley for converting peptide sequences.[citation needed] The simple pre-sequence (e.g. Lysine (Lysn); Glutamic Acid (Glun); (LysGlu)n) that is incorporated at the C-terminus of the peptide to induce an alpha-helix-like structure. This can potentially increase biological half-life, improve peptide stability and inhibit enzymatic degradation without altering pharmacological activity or profile of action.[58][59]

Cyclic peptides edit

On resin cyclization edit

Peptides can be cyclized on a solid support. A variety of cyclization reagents can be used such as HBTU/HOBt/DIEA, PyBop/DIEA, PyClock/DIEA.[60] Head-to-tail peptides can be made on the solid support. The deprotection of the C-terminus at some suitable point allows on-resin cyclization by amide bond formation with the deprotected N-terminus. Once cyclization has taken place, the peptide is cleaved from resin by acidolysis and purified.[61][62]

The strategy for the solid-phase synthesis of cyclic peptides is not limited to attachment through Asp, Glu or Lys side chains. Cysteine has a very reactive sulfhydryl group on its side chain. A disulfide bridge is created when a sulfur atom from one Cysteine forms a single covalent bond with another sulfur atom from a second cysteine in a different part of the protein. These bridges help to stabilize proteins, especially those secreted from cells. Some researchers use modified cysteines using S-acetomidomethyl (Acm) to block the formation of the disulfide bond but preserve the cysteine and the protein's original primary structure.[63]

Off-resin cyclization edit

Off-resin cyclization is a solid-phase synthesis of key intermediates, followed by the key cyclization in solution phase, the final deprotection of any masked side chains is also carried out in solution phase. This has the disadvantages that the efficiencies of solid-phase synthesis are lost in the solution phase steps, that purification from by-products, reagents and unconverted material is required, and that undesired oligomers can be formed if macrocycle formation is involved.[64]

The use of pentafluorophenyl esters (FDPP,[65] PFPOH[66]) and BOP-Cl[67] are useful for cyclising peptides.

History edit

The first protected peptide was synthesised by Theodor Curtius in 1882 and the first free peptide was synthesised by Emil Fischer in 1901.[3]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d Isidro-Llobet A, Alvarez M, Albericio F (June 2009). "Amino acid-protecting groups". Chemical Reviews. 109 (6): 2455–2504. doi:10.1021/cr800323s. hdl:2445/69570. PMID 19364121. S2CID 90409290.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chan WC, White PD (2000). Fmoc Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis: A Practical Approach. Oxford, UK: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-963724-9.

- ^ a b Jaradat DM (January 2018). "Thirteen decades of peptide synthesis: key developments in solid phase peptide synthesis and amide bond formation utilized in peptide ligation". Amino Acids. 50 (1): 39–68. doi:10.1007/s00726-017-2516-0. PMID 29185032. S2CID 3680612.

- ^ Merrifield RB (1963). "Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis. I. The Synthesis of a Tetrapeptide". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 85 (14): 2149–2154. doi:10.1021/ja00897a025.

- ^ Mitchell AR (2008). "Bruce Merrifield and solid-phase peptide synthesis: a historical assessment". Biopolymers. 90 (3): 175–184. doi:10.1002/bip.20925. PMID 18213693. S2CID 30382016.

- ^ Mant CT, Chen Y, Yan Z, Popa TV, Kovacs JM, Mills JB, et al. (2007). "HPLC analysis and purification of peptides". Peptide Characterization and Application Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 386. Humana Press. pp. 3–55. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-430-8_1. ISBN 978-1-59745-430-8. PMC 7119934. PMID 18604941.

- ^ "Custom peptide synthesis service. HPLC refers to High Performance Liquid Chromatography". Remetide Biotech. November 2021.

- ^ Lundemann-Hombourger O (May 2013). "The ideal peptide plant" (PDF). Speciality Chemicals Magazine: 30–33.

- ^ Tickler AK, Clippingdale AB, Wade JD (August 2004). "Amyloid-beta as a "difficult sequence" in solid phase peptide synthesis". Protein and Peptide Letters. 11 (4): 377–384. doi:10.2174/0929866043406986. PMID 15327371.

- ^ a b El-Faham A, Albericio F (November 2011). "Peptide coupling reagents, more than a letter soup". Chemical Reviews. 111 (11): 6557–6602. doi:10.1021/cr100048w. PMID 21866984.

- ^ a b c d e Montalbetti CA, Falque V (2005). "Amide bond formation and peptide coupling". Tetrahedron. 61 (46): 10827–10852. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2005.08.031.

- ^ Valeur E, Bradley M (February 2009). "Amide bond formation: beyond the myth of coupling reagents". Chemical Society Reviews. 38 (2): 606–631. doi:10.1039/B701677H. PMID 19169468.

- ^ El-Faham A, Albericio F (November 2011). "Peptide coupling reagents, more than a letter soup". Chemical Reviews. 111 (11): 6557–6602. doi:10.1021/cr100048w. PMID 21866984.

- ^ Singh S (January 2018). "CarboMAX - Enhanced Peptide Coupling at Elevated Temperatures" (PDF). AP Note. 0124: 1–5.

- ^ Joullié MM, Lassen KM (2010). "Evolution of Amide Bond Formation". Arkivoc. viii (8): 189–250. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0011.816. hdl:2027/spo.5550190.0011.816.

- ^ Subirós-Funosas R, Prohens R, Barbas R, El-Faham A, Albericio F (September 2009). "Oxyma: an efficient additive for peptide synthesis to replace the benzotriazole-based HOBt and HOAt with a lower risk of explosion". Chemistry: A European Journal. 15 (37): 9394–9403. doi:10.1002/chem.200900614. PMID 19575348.

- ^ Albericio F, Bofill JM, El-Faham A, Kates SA (1998). "Use of Onium Salt-Based Coupling Reagents in Peptide Synthesis". J. Org. Chem. 63 (26): 9678–9683. doi:10.1021/jo980807y.

- ^ J. Hiebl et al, J. Pept. Res. (1999), 54, 54

- ^ a b c Albericio F (2000). Solid-Phase Synthesis: A Practical Guide (1 ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 848. ISBN 978-0-8247-0359-2.

- ^ Kent SB (1988). "Chemical synthesis of peptides and proteins". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 57 (1): 957–989. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004521. PMID 3052294.

- ^ Feinberg RS, Merrifield RB (1974). "Zinc chloride-catalyzed chloromethylation of resins for solid phase peptide synthesis". Tetrahedron. 30 (17): 3209–3212. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)97575-1.

- ^ Hermkens PH, Ottenheijm HC, Rees DC (1997). "Solid-phase organic reactions II: A review of the literature Nov 95 – Nov 96". Tetrahedron. 53 (16): 5643–5678. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(97)00279-2.

- ^ Schnolzer MA, Jones A, Alewood D, Kent SB (2007). "In Situ Neutralization in Boc-chemistry Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis". Int. J. Peptide Res. Therap. 13 (1–2): 31–44. doi:10.1007/s10989-006-9059-7. S2CID 28922643.

- ^ Beyermann M, Bienert M (1992). "Synthesis of difficult peptide sequences: A comparison of Fmoc-and BOC-technique". Tetrahedron Letters. 33 (26): 3745–3748. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(92)80014-B.

- ^ Jones J (1992). Amino Acid and Peptide Synthesis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Luna OF, Gomez J, Cárdenas C, Albericio F, Marshall SH, Guzmán F (November 2016). "Deprotection Reagents in Fmoc Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis: Moving Away from Piperidine?". Molecules. 21 (11): 1542. doi:10.3390/molecules21111542. PMC 6274427. PMID 27854291.

- ^ Huang H, Rabenstein DL (May 1999). "A cleavage cocktail for methionine-containing peptides". The Journal of Peptide Research. 53 (5): 548–553. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3011.1999.00059.x. PMID 10424350.

- ^ "Cleavage Cocktails; Reagent B; Reagent H; Reagent K; Reagent L; Reagent R". AAPPTEC. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Dick F (1995). "Acid Cleavage/Deprotection in Fmoc/tBiu Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis". In Pennington MW, Dunn BM (eds.). Peptide Synthesis Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 35. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. 63–72. doi:10.1385/0-89603-273-6:63. ISBN 978-1-59259-522-8. PMID 7894609.

- ^ a b c d Katsoyannis PG, ed. (1973). The Chemistry of Polypeptides. New York: Plenum Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-4571-8. ISBN 978-1-4613-4571-8. S2CID 35144893.

- ^ a b Bergmann M, Zervas L (1932). "Über ein allgemeines Verfahren der Peptid-Synthese". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 65 (7): 1192–1201. doi:10.1002/cber.19320650722.

- ^ Thieriet N, Alsina J, Giralt E, Guibé F, Albericio F (1997). "Use of Alloc-amino acids in solid-phase peptide synthesis. Tandem deprotection-coupling reactions using neutral conditions". Tetrahedron Letters. 38 (41): 7275–7278. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(97)01690-0.

- ^ Shin DS, Kim DH, Chung WJ, Lee YS (September 2005). "Combinatorial solid phase peptide synthesis and bioassays". Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 38 (5): 517–525. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2005.38.5.517. PMID 16202229.

- ^ Price JV, Tangsombatvisit S, Xu G, Yu J, Levy D, Baechler EC, et al. (September 2012). "On silico peptide microarrays for high-resolution mapping of antibody epitopes and diverse protein-protein interactions". Nature Medicine. 18 (9): 1434–1440. doi:10.1038/nm.2913. PMC 3491111. PMID 22902875.

- ^ Hedberg-Dirk EL, Martinez UA (8 August 2010). "Large-Scale Protein Arrays Generated with Interferometric Lithography for Spatial Control of Cell-Material Interactions". Journal of Nanomaterials. 2010: e176750. doi:10.1155/2010/176750. ISSN 1687-4110.

- ^ Fodor SP, Read JL, Pirrung MC, Stryer L, Lu AT, Solas D (February 1991). "Light-directed, spatially addressable parallel chemical synthesis". Science. 251 (4995): 767–773. Bibcode:1991Sci...251..767F. doi:10.1126/science.1990438. PMID 1990438.

- ^ Tam JP, Wu CR, Liu W, Zhang JW (1991). "Disulfide bond formation in peptides by dimethyl sulfoxide. Scope and applications". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113 (17): 6657–6662. doi:10.1021/ja00017a044.

- ^ Sieber P, Kamber B, Hartmann A, Jöhl A, Riniker B, Rittel W (January 1977). "[Total synthesis of human insulin. IV. Description of the final steps (author's transl)]". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 60 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1002/hlca.19770600105. PMID 838597.

- ^ a b Spears RJ, McMahon C, Chudasama V (October 2021). "Cysteine protecting groups: applications in peptide and protein science". Chemical Society Reviews. 50 (19): 11098–11155. doi:10.1039/D1CS00271F. PMID 34605832. S2CID 238258277.

- ^ Laps S, Atamleh F, Kamnesky G, Sun H, Brik A (February 2021). "General synthetic strategy for regioselective ultrafast formation of disulfide bonds in peptides and proteins". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 870. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..870L. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21209-0. PMC 7870662. PMID 33558523.

- ^ Ottl J, Battistuta R, Pieper M, Tschesche H, Bode W, Kühn K, Moroder L (November 1996). "Design and synthesis of heterotrimeric collagen peptides with a built-in cystine-knot. Models for collagen catabolism by matrix-metalloproteases". FEBS Letters. 398 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01212-4. PMID 8946948. S2CID 24688988.

- ^ a b Akaji K, Fujino K, Tatsumi T, Kiso Y (1993). "Total synthesis of human insulin by regioselective disulfide formation using the silyl chloride-sulfoxide method". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 115 (24): 11384–11392. doi:10.1021/ja00077a043.

- ^ Pedersen SL, Tofteng AP, Malik L, Jensen KJ (March 2012). "Microwave heating in solid-phase peptide synthesis". Chemical Society Reviews. 41 (5): 1826–1844. doi:10.1039/C1CS15214A. PMID 22012213.

- ^ Kappe CO, Stadler A, Dallinger D (2012). Microwaves in Organic and Medicinal Chemistry. Methods and Principles in Medicinal Chemistry. Vol. 52 (Second ed.). Wiley. ISBN 9783527331857.

- ^ Dryland A, Sheppard RC (1986). "Peptide synthesis. Part 8. A system for solid-phase synthesis under low pressure continuous flow conditions". Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1: 125–137. doi:10.1039/p19860000125. ISSN 0300-922X.

- ^ Simon MD, Heider PL, Adamo A, Vinogradov AA, Mong SK, Li X, et al. (March 2014). "Rapid flow-based peptide synthesis". ChemBioChem. 15 (5): 713–720. doi:10.1002/cbic.201300796. PMC 4045704. PMID 24616230.

- ^ Spare LK, Laude V, Harman DG, Aldrich-Wright JR, Gordon CP (2018). "An optimised approach for continuous-flow solid-phase peptide synthesis utilising a rudimentary flow reactor". Reaction Chemistry & Engineering. 3 (6): 875–882. doi:10.1039/C8RE00190A. ISSN 2058-9883.

- ^ Gordon CP (January 2018). "The renascence of continuous-flow peptide synthesis - an abridged account of solid and solution-based approaches". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 16 (2): 180–196. doi:10.1039/C7OB02759A. PMID 29255827.

- ^ Sletten ET, Nuño M, Guthrie D, Seeberger PH (December 2019). "Real-time monitoring of solid-phase peptide synthesis using a variable bed flow reactor". Chemical Communications. 55 (97): 14598–14601. doi:10.1039/C9CC08421E. hdl:21.11116/0000-0005-3E5F-D. PMID 31742308.

- ^ Muir TW, Sondhi D, Cole PA (June 1998). "Expressed protein ligation: a general method for protein engineering". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (12): 6705–6710. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.6705M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.12.6705. PMC 22605. PMID 9618476.

- ^ Nilsson BL, Soellner MB, Raines RT (2005). "Chemical synthesis of proteins". Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 34: 91–118. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144700. PMC 2845543. PMID 15869385.

- ^ Kent SB (February 2009). "Total chemical synthesis of proteins". Chemical Society Reviews. 38 (2): 338–351. doi:10.1039/B700141J. PMID 19169452. S2CID 5432012.

- ^ Nyfeler R (7 November 1994). Peptide synthesis via fragment condensation. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 35. New Jersey: Humana Press. pp. 303–316. doi:10.1385/0-89603-273-6:303. ISBN 978-0-89603-273-6. PMID 7894607.

- ^ Flood DT, Hintzen JC, Bird MJ, Cistrone PA, Chen JS, Dawson PE (September 2018). "Leveraging the Knorr Pyrazole Synthesis for the Facile Generation of Thioester Surrogates for use in Native Chemical Ligation". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 57 (36): 11634–11639. doi:10.1002/anie.201805191. PMC 6126375. PMID 29908104.

- "Peptide Thioesters for Native Chemical Ligation". Chemistry Views. 9 September 2018.

- ^ Aranko AS, Wlodawer A, Iwaï H (August 2014). "Nature's recipe for splitting inteins". Protein Engineering, Design & Selection. 27 (8): 263–271. doi:10.1093/protein/gzu028. PMC 4133565. PMID 25096198.

- ^ Reddington SC, Howarth M (December 2015). "Secrets of a covalent interaction for biomaterials and biotechnology: SpyTag and SpyCatcher". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 29: 94–99. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.10.002. PMID 26517567.

- ^ Haridas V, Sadanandan S, Dheepthi NU (September 2014). "Sortase-based bio-organic strategies for macromolecular synthesis". ChemBioChem. 15 (13): 1857–1867. doi:10.1002/cbic.201402013. PMID 25111709. S2CID 28999405.

- ^ Kapusta DR, Thorkildsen C, Kenigs VA, Meier E, Vinge MM, Quist C, Petersen JS (August 2005). "Pharmacodynamic characterization of ZP120 (Ac-RYYRWKKKKKKK-NH2), a novel, functionally selective nociceptin/orphanin FQ peptide receptor partial agonist with sodium-potassium-sparing aquaretic activity". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 314 (2): 652–660. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.083436. PMID 15855355. S2CID 27318583.

- ^ Rizzi A, Rizzi D, Marzola G, Regoli D, Larsen BD, Petersen JS, Calo' G (October 2002). "Pharmacological characterization of the novel nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor ligand, ZP120: in vitro and in vivo studies in mice". British Journal of Pharmacology. 137 (3): 369–374. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704894. PMC 1573505. PMID 12237257.

- ^ Davies JS (August 2003). "The cyclization of peptides and depsipeptides". Journal of Peptide Science. 9 (8): 471–501. doi:10.1002/psc.491. PMID 12952390.

- ^ Lambert JN, Mitchell JP, Roberts KD (1 January 2001). "The synthesis of cyclic peptides". Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1 (5): 471–484. doi:10.1039/B001942I. ISSN 1364-5463.

- ^ Chow HY, Zhang Y, Matheson E, Li X (September 2019). "Ligation Technologies for the Synthesis of Cyclic Peptides". Chemical Reviews. 119 (17): 9971–10001. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00657. PMID 31318534. S2CID 197666575.

- ^ Sieber P, Kamber B, Riniker B, Rittel W (10 December 1980). "Iodine Oxidation of S-Trityl- and S-Acetamidomethyl-cysteine-peptides Containing Tryptophan: Conditions Leading to the Formation of Tryptophan-2-thioethers". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 63 (8): 2358–2363. doi:10.1002/hlca.19800630826.

- ^ Scott P (13 October 2009). Linker Strategies in Solid-Phase Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 135–137. ISBN 978-0-470-74905-0.

- ^ Nicolaou KC, Natarajan S, Li H, Jain NF, Hughes R, Solomon ME, et al. (October 1998). "Total Synthesis of Vancomycin Aglycon-Part 1: Synthesis of Amino Acids 4-7 and Construction of the AB-COD Ring Skeleton". Angewandte Chemie. 37 (19): 2708–2714. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981016)37:19<2708::AID-ANIE2708>3.0.CO;2-E. PMID 29711605.

- ^ East SP, Joullié MM (1998). "Synthetic studies of 14-membered cyclopeptide alkaloids". Tetrahedron Lett. 39 (40): 7211–7214. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(98)01589-5.

- ^ Baker R, Castro JL (1989). "The total synthesis of (+)-macbecin I". Chem. Commun. (6): 378–381. doi:10.1039/C39890000378.

Further reading edit

- Stewart JM, Young JD (1984). Solid phase peptide synthesis (2nd ed.). Rockford, IL: Pierce Chemical Company. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-935940-03-9.

- Kent SB (1988). "Chemical Synthesis of Peptides and Proteins". Annual Review of Biochemistry. Vol. 57. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. pp. 957–989. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004521. PMID 3052294.

- Atherton E, Sheppard RC (1989). Solid Phase peptide synthesis: a practical approach. Oxford, England: IRL Press. ISBN 978-0-19-963067-7.

- Chan W, White P, eds. (2000). Fmoc Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis: A Practical Approach. Practical Approach Series, Issue 222. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199637245. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Fields GB (February 2002). "Introduction to peptide synthesis". Current Protocols in Protein Science. Chapter 18: 18.1.1–18.1.9. doi:10.1002/0471140864.ps1801s26. ISBN 978-0-471-14086-3. PMC 3564544. PMID 18429226.

- Bodanszky M (2012). Principles of Peptide Synthesis. Reactivity and Structure: Concepts in Organic Chemistry, Volume 16. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3642967634. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Bodanszky M, Bodanszky A (2013). The Practice of Peptide Synthesis. Reactivity and Structure: Concepts in Organic Chemistry, Volume 21. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-96835-8. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Benoiton NL (2016). Chemistry of Peptide Synthesis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press / Taylor & Frances. ISBN 978-1-4200-2769-3. Retrieved 12 November 2016.