Summary

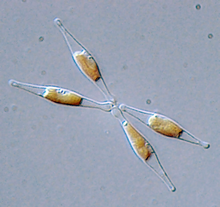

Phaeodactylum tricornutum is a diatom. It is the only species in the genus Phaeodactylum. Unlike other diatoms, P. tricornutum can exist in different morphotypes (fusiform, triradiate, and oval) and changes in cell shape can be stimulated by environmental conditions.[1] This feature can be used to explore the molecular basis of cell shape control and morphogenesis. Unlike most diatoms, P. tricornutum can grow in the absence of silicon and can survive without making silicified frustules.[2] This provides opportunities for experimental exploration of silicon-based nanofabrication in diatoms.

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | |

| Superphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | Phaeodactylineae

|

| Family: | Phaeodactylaceae

|

| Genus: | Phaeodactylum

|

| Species: | P. tricornutum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum Bohlin, 1897

| |

Another peculiarity is that during asexual reproduction the frustules do not appear to become smaller. This allows continuous culture without need for sexual reproduction. It is not known if P. tricornutum can reproduce sexually. To date no substantial evidence has been found to support sexual reproduction in a laboratory or other setting. Although P. tricornutum can be considered to be an atypical pennate diatom, it is one of the main diatom model species. A transformation protocol has been established and RNAi vectors are available.[3][4] This makes molecular genetic studies much easier.

History edit

Phaeodactylum tricornutum was first described in the triradiate morphotype by Bohlin in 1897.[5] Recordings of the first cultures of P. tricornutum were published by Allen and Nelson in 1910, although it was misidentified as Nitzschia colsterium,W. Sm., forma miuntissima.[6] The isolate was later correctly revised as P. tricorntum by J.C. Lewin in 1958.[7] This strain among other later isolates are still maintained in culture collections around the world.[8]

Genome sequencing edit

Phaeodactylum tricornutum is one of a handful of diatoms whose genome has been sequenced. As of 2023, P. tricornutum is the only diatom for which a telomere-to-telomere genome assembly exists.[9] P. tricornutum is a diploid with 25 pairs of nuclear chromosomes.

P. tricornutum has emerged as a potential microalgal energy source. It grows rapidly and storage lipids constitute about 20-30% of its dry cell weight under standard culture conditions.[10][11] Nitrogen limitation can induce neutral lipid accumulation in P. tricornutum, indicating possible strategies for improving microalgal biodiesel production.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ De Martino, A; Meichenin, A; Shi, J; Pan, KH; Bowler, C (2007). "Genetic and phenotypic characterization of Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Bacillariophyceae) accessions". Journal of Phycology. 43 (5): 992–1009. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00384.x. S2CID 85769550.

- ^ Chuang, Chia-Ying; Santschi, Peter H.; Jiang, Yuelu; Ho, Yi-Fang; Quigg, Antonietta; Guo, Laodong; Ayranov, Marin; Schumann, Dorothea (2014-06-20). "Important role of biomolecules from diatoms in the scavenging of particle-reactive radionuclides of thorium, protactinium, lead, polonium, and beryllium in the ocean: A case study with Phaeodactylum tricornutum". Limnology and Oceanography. 59 (4): 1256–1266. Bibcode:2014LimOc..59.1256C. doi:10.4319/lo.2014.59.4.1256. ISSN 0024-3590. S2CID 98646215.

- ^ Apt, K. E.; et al. (1996). "Molecular and General Genetics Stable nuclear transformation of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum". Molecular and General Genetics. 252 (5): 572–579. doi:10.1007/BF02172403. PMID 8914518. S2CID 29664801.

- ^ De Riso, V; Raniello, R.; Maumus, F.; Rogato, A.; Bowler, C.; Falciatore, A. (2009). "Gene silencing in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum". Nucleic Acids Research. 37 (14): e96. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp448. PMC 2724275. PMID 19487243.

- ^ Bohlin, von K. (1897). Zur Morphologie und Biologie einzelliger Algen. p. 520.

- ^ Allen, E. J.; Nelson, E.W. (1910). On the Artificial Culture of Marine Plankton Organisms. pp. 421–74.

- ^ Lewin, J.C. (1958). "The taxonomic position of Phaeodactylum tricornutum". Journal of General Microbiology. 18 (2): 427–32. doi:10.1099/00221287-18-2-427. PMID 13525659.

- ^ De Martino, Alessandra; Meichenin, Agnes; Shi, Juan; Pan, Kehou; Bowler, Chris. "Genetic and phenotypic characterization of Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Bacillariophyceae) accessions". Journal of Phycology (43): 992–1009.

- ^ Giguere, Daniel J.; Bahcheli, Alexander T.; Slattery, Samuel S.; Patel, Rushali R.; Browne, Tyler S.; Flatley, Martin; Bogumil, Karas J.; Edgell, David R.; Gregory, Gloor B. (2022). "Telomere-to-telomere genome assembly of Phaeodactylum tricornutum". PeerJ. 10 (e13607): e13607. doi:10.7717/peerj.13607. PMC 9266582. PMID 35811822.

- ^ Chisti, Y (May–Jun 2007). "Biodiesel from microalgae". Biotechnology Advances. 25 (3): 294–306. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.02.001. PMID 17350212. S2CID 18234512.

- ^ Yang, ZK; Niu, YF; Ma, YH; Xue, J; Zhang, MH; Yang, WD; Liu, JS; Lu, SH; Guan, Y; Li, HY (May 4, 2013). "Molecular and cellular mechanisms of neutral lipid accumulation in diatom following nitrogen deprivation". Biotechnology for Biofuels. 6 (1): 67. doi:10.1186/1754-6834-6-67. PMC 3662598. PMID 23642220.

External links edit

- Yongmanitchai, W; Ward, O. P. (1991). "Growth of and Omega-3 Fatty Acid Production by Phaeodactylum tricornutum under Different Culture Conditions". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 57 (2): 419–425. Bibcode:1991ApEnM..57..419Y. doi:10.1128/aem.57.2.419-425.1991. PMC 182726. PMID 2014989.

- journals.tubitak.gov.tr The Growth of Continuous Cultures of the Phytoplankton Phaeodactylum Tricornutum (pdf)

- [1] picture of phaeodactylum tricornutum