Summary

Pietro Perugino (US: /ˌpɛrəˈdʒiːnoʊ, -ruːˈ-/ PERR-ə-JEE-noh, -oo-,[1][2][3] Italian: [ˈpjɛːtro peruˈdʒiːno]; born Pietro Vannucci or Pietro Vanucci;[4] c. 1446/1452 – 1523), an Italian Renaissance painter of the Umbrian school, developed some of the qualities that found classic expression in the High Renaissance. Raphael became his most famous pupil.

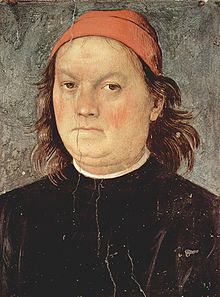

Pietro Perugino | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, 1497–1500 | |

| Born | Pietro Vannucci c. 1446 |

| Died | 1523 (aged 76–77) Fontignano, Papal States (now Umbria, Italy) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Andrea del Verrocchio |

| Known for | Painting, fresco |

| Notable work | The Delivery of the Keys |

| Movement | Italian Renaissance |

Early years edit

Pietro Vannucci was born in Città della Pieve, Umbria, the son of Cristoforo Maria Vannucci. His nickname characterizes him as from Perugia, the chief city of Umbria. Scholars continue to dispute the socioeconomic status of the Vannucci family. While certain academics maintain that Vannucci worked his way out of poverty, others argue that his family was among the wealthiest in the town.[5] His exact date of birth is not known, but based on his age at death that was mentioned by Vasari and Giovanni Santi, it is believed that he was born between 1446 and 1452.[5]

Pietro most likely began studying painting in local workshops in Perugia such as those of Bartolomeo Caporali or Fiorenzo di Lorenzo.[5] The date of the first Florentine sojourn is unknown; some make it as early as 1466-1470, others push the date to 1479.[5] According to Vasari, he was apprenticed to the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio alongside Leonardo da Vinci, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Lorenzo di Credi, Filippino Lippi, and others. Piero della Francesca is thought to have taught him perspective form. In 1472, he must have completed his apprenticeship since he was enrolled as a master in the Confraternity of St Luke. Pietro, although very talented, was not extremely enthusiastic about his work.[6]

Perugino was one of the earliest Italian practitioners of oil painting. Some of his early works were extensive frescoes for the convent of the Ingessati fathers, destroyed during the Siege of Florence; he produced many cartoons for them also, which they executed with brilliant effect in stained glass. A good specimen of his early style in tempera is the tondo (circular picture) in the Musée du Louvre of the Virgin and Child Enthroned between Saints.

Rome edit

Perugino returned from Florence to Perugia, where his Florentine training showed in the Adoration of the Magi for the church of Santa Maria dei Servi of Perugia (c. 1476). In about 1480, he was called to Rome by Sixtus IV to paint fresco panels for the Sistine Chapel walls. The frescoes he executed there included Moses and Zipporah (often attributed to Luca Signorelli), the Baptism of Christ, and Delivery of the Keys. Pinturicchio accompanied Perugino to Rome, and was made his partner, receiving a third of the profits. He may have done some of the Zipporah subject. The Sistine frescoes were the major high Renaissance commission in Rome. The altar wall was also painted with the Assumption, the Nativity, and Moses in the Bulrushes. These works were later destroyed to make a space for Michelangelo's Last Judgement.

Between 1486 and 1499, Perugino worked mostly in Florence, making one journey to Rome and several to Perugia, where he may have maintained a second studio. He had an established studio in Florence, and received a great number of commissions. His Pietà (1483–1493) in the Uffizi is an uncharacteristically stark work that avoids Perugino's sometimes too easy sentimental piety.

According to Vasari, Perugino was to return to Florence in September 1493 to marry Chiara, daughter of architect Luca Fancelli.[7] The same year, Perugino made Florence his permanent home once again,[8] though he continued to accept some work elsewhere.

Later career edit

In 1499, the guild of the cambio (money-changers or bankers) of Perugia asked him to decorate their audience-hall, the Sala delle Udienze del Collegio del Cambio. The humanist Francesco Maturanzio acted as his consultant. This extensive scheme, which may have been finished by 1500, comprised the painting of the vault, showing the seven planets and the signs of the zodiac (Perugino being responsible for the designs and his pupils most probably for the execution), and the representation on the walls of two sacred subjects: the Nativity and Transfiguration; in addition, the Eternal Father, the cardinal virtues of Justice, Prudence, Temperance, Fortitude, Cato as the emblem of wisdom, and numerous life-sized figures of classic worthies, prophets, and sibyls figured in the program. On the mid-pilaster of the hall Perugino placed his own portrait in bust-form. It is probable that Raphael, who in boyhood, toward 1496, had been placed by his uncles under the tuition of Perugino, bore a hand in the work of the vaulting.

Perugino was made one of the priors of Perugia in 1501. On one occasion Michelangelo told Perugino to his face that he was a bungler in art (goffo nell arte): Vannucci brought an action for defamation of character, unsuccessfully. Put on his mettle by this mortifying transaction, he produced the masterpiece of the Madonna and Saints for the Certosa of Pavia, now disassembled and scattered among museums: the only portion in the Certosa is God the Father with cherubim. An Annunciation has disappeared; three panels, the Virgin adoring the infant Christ, St. Michael, and St. Raphael with Tobias are among the treasures of the National Gallery, London. This was succeeded in 1504–1507 by the Annunziata Altarpiece for the high altar of the Basilica dell'Annunziata in Florence, in which he replaced Filippino Lippi. The work was a failure, being accused of lack of innovation. Perugino lost his students; and toward 1506 he once more and finally, abandoned Florence, going to Perugia, and thence in a year or two to Rome.

Pope Julius II had summoned Perugino to paint the Stanza of the Incendio del Borgo in the Vatican City; but he soon preferred a younger competitor, Raphael, who had been trained by Perugino; and Vannucci, after painting the ceiling with figures of God the Father in different glories, in five medallion-subjects, retired from Rome to Perugia from 1512. Among his latest works, many of which decline into repetitious studio routine, one of the best is the extensive altarpiece (painted between 1512 and 1517) of the church of San Agostino in Perugia, also now dispersed.

Perugino's last frescoes were painted in the church of the Madonna delle Lacrime in Trevi (1521, signed and dated), the monastery of Sant'Agnese in Perugia, and in 1522 for the church of Castello di Fortignano. Both series have disappeared from their places, the second being now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. He was still at Fontignano in 1523 when he died of the plague. Like other plague victims, he was hastily buried in an unconsecrated field, the precise spot now unknown.

Vasari is the main source stating that Perugino had very little religion and openly doubted the soul's immortality. Perugino in 1494 painted his own portrait, now in the Uffizi Gallery, and into it, he introduced a scroll entitled Timete Deum (Fear God: Revelation 14:7). That an open disbeliever should inscribe himself with Timete Deum seems odd. The portrait in question shows a plump face, with small dark eyes, a short but well-cut nose, and sensuous lips; the neck is thick, the hair bushy and frizzled, and the general air imposing. The later portrait in the Cambio of Perugia shows the same face with traces of added years. Perugino died with considerable property, leaving three sons.

In 1495, he signed and dated a Deposition for the Florentine convent of Santa Chiara (Palazzo Pitti). Toward 1496 he frescoed a crucifixion, commissioned in 1493 for Maria Maddalena de' Pazzi, Florence (the Pazzi Crucifixion). The attribution to him of the painting of the marriage of Joseph and the Virgin Mary (the Sposalizio) now in the museum of Caen, which indisputably served as the original, to a great extent, of the still more famous Sposalizio painted by Raphael in 1504 (Brera, Milan), is now questioned, and it is assigned to Lo Spagna. A vastly finer work of Perugino's was the polyptych of the Ascension of Christ painted ca 1496–98 for the church of S. Pietro of Perugia, (Municipal Museum, Lyon); the other portions of the same altarpiece are dispersed in other galleries.

In the chapel of the Disciplinati of Città della Pieve is an Adoration of the Magi, a square of 6.5 m containing about thirty life-sized figures; this was executed, with scarcely credible celerity, from March 1 to 25 (or thereabouts) in 1505, and must no doubt be in great part the work of Vannucci's pupils. In 1507, when the master's work had for years been in a course of decline and his performances were generally weak, he produced, nevertheless, one of his best paintings, the Virgin between Saint Jerome and Saint Francis, now in the Palazzo Penna. In the church of S. Onofrio in Florence is a much lauded and much debated fresco of the Last Supper, a careful and blandly correct but uninspired work; it has been ascribed to Perugino by some connoisseurs, by others to Raphael; it may more probably be by some different pupil of the Umbrian master.

Among his pupils were Raphael, upon whose early work Perugino's influence is most noticeable, Pompeo Cocchi,[9]: 61 Eusebio da San Giorgio,[9]: 62 Mariano di Eusterio,[9]: 63 and Giovanni di Pietro (lo Spagna).

Monuments edit

Perugia dedicated an important monument to Perugino built in 1923 by the sculptor Enrico Quattrini and today visible in the Carducci Gardens.

Major works edit

- The Delivery of the Keys (1481–1482) — Fresco, 335 × 600 cm, Sistine Chapel, Vatican City

- Crucifixion (the Galitzin triptych, 1480s) — painted for San Domenico at San Gimignano, National Gallery, Washington

- Pietà (c. 1483–1493) -Oil on panel, 168x176 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

- Cathedral of Saint Romulus of Fiesole - altarpiece, Fiesole, Italy

- Annunciation of Fano (c. 1488–1490) -Oil on panel, 212x172 cm, church of Santa Maria Nuova, Fano

- Portrait of Lorenzo di Credi (1488) -Oil on panel transferred to canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- St. Sebastian (c. 1490) — Oil on panel, 174 × 88 cm, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

- St. Sebastian (c. 1490–1500) — Panel, 176 × 116 cm, Louvre, Paris

- St. Sebastian (after 1490) — Oil on wood, 110 × 62 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- The Virgin appearing to St. Bernard (c. 1490–1494) — Oil on wood, 173 × 170 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

- Albani Torlonia Altarpiece (1491) - Tempera on panel, 174 x 88 cm, Torlonia Collection, Rome

- Madonna with Child Enthroned between Saints John the Baptist and Sebastian (1493) - Oil on panel, 178x164 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

- St Sebastian (Perugino, Hermitage) (1493–1494) — Oil and tempera on panel, 53.8 × 39.5 cm, The Hermitage, St. Petersburg

- Portrait of Francesco delle Opere (1494) - Oil on panel, 52 x 44 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

- Certosa di Pavia Altarpiece (1496–1500) - Oil on panel, 52 x 44 cm, National Gallery, London

- Decemviri Altarpiece (1497) -Oil on panel, 193x165 cm, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome

- Fano Altarpiece (1497) -Oil on panel, 262x215 cm, church of Santa Maria Nuova, Fano

- San Francesco al Prato Resurrection (c. 1499–1501) -Oil on panel, 233x165 cm, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome

- Vallombrosa Altarpiece (1500) -Oil on panel, 415x246 cm, Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence

- Tezi Altarpiece (c. 1500) -Oil on panel, 180x158 cm, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria, Perugia

- Madonna in Glory with Saints (c. 1500–1501) -Oil on panel, 330x265 cm, Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna

- Marriage of the Virgin (1500–1504) — Oil on wood, 234 × 185, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen

- St. Sebastian Bound to a Column (c. 1500–1510) — Oil on canvas, 181 × 115 cm, São Paulo Museum of Art, São Paulo, Brazil

- Combat of Love and Chastity (1503) — Tempera on canvas, 160 x 191 cm, painted for Isabella d'Este studiolo, Louvre, Paris

- Annunziata Polyptych (1504–1507) – Oil on panel, 334 x 225 cm (the main panel), Gallerie dell'Accademia and Annunziata, Florence

- The Nativity: the Virgin, St. Joseph, and the Shepherds adoring the Infant Christ (c. 1522) — Fresco transferred to canvas from S. Maria Assunta, at Fontignano, 254 x 594 cm, Victoria & Albert Museum, London

- Ascension of Christ (Sansepolcro Altarpiece; c. 1510) - Oil on panel, 332.5 x 266 cm, Sansepolcro Cathedral

- Saint Bartholomew (1512–1523) – Oil on Panel, 89 x 71 cm, Part of polyptych Birmingham Museum of Art

- Religious works, details, portraits

-

Assumption of the Virgin (c. 1506)

-

Decemviri Altarpiece (1495)

-

The Virgin and Child with Saints Jerome and Francis (c. 1507)

-

Virgin and Child between Saints Rosa and Catherine (c. 1493)

-

Detail, Madonna

-

Detail, Prophets and Sibyls, fresco

-

Detail, Prophets and Sibyls, fresco

-

Detail, The Delivery of the Keys, fresco

-

Portrait of a boy (1495)

-

Portrait of Francesco delle Opere

-

Detail, Madonna with Child

-

Portrait of Lorenzo di Credi

See also edit

- Berto di Giovanni (1475–1529) – a pupil of Perugino

References edit

- ^ "Perugino". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Perugino". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Perugino". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio (1897) [1550]. "Pietro Perugino, Painter". In Blashfield, Edwin Howland; Blashfield, Evangeline Wilbour; Hopkins, Albert Allis (eds.). Lives of Seventy of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. Vol. 2. Translated by Foster, Mrs. Jonathan. London: C. Scribner's sonsGeorge Bell and Sons. p. 316. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d Garibaldi, Vittoria (2004). "Perugino". Pittori del Rinascimento. Florence: Scala. ISBN 88-8117-099-X.

- ^ "Pietro Perugino". The Athenaeum (3810): 584. 11 March 1900. ISSN 1747-3594.

- ^ Becherucci, Luisa (1969). The Complete Work of Raphael. New York: Reynal and Co., William Morrow and Company. p. 12.

- ^ Becherucci, Luisa (1969). The Complete Work of Raphael. New York: Reynal and Co., William Morrow and Company. p. 14.

- ^ a b c Catalogo dei quadri che si conservano nella Pinacoteca Vannucci in Perugia, by Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria, (1903).

Sources edit

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rossetti, William Michael (1911). "Perugino, Pietro". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). p. 279-280.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links edit

- Media related to Pietro Perugino at Wikimedia Commons

- Pietro Perugino at the National Gallery of Art