Summary

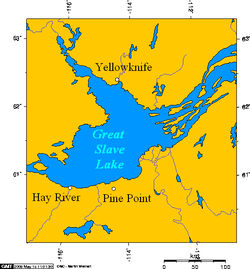

Pine Point is an abandoned locality that formerly held town status near the south shore of Great Slave Lake between the towns of Hay River and Fort Resolution in the Northwest Territories of Canada. It was built to serve the work force at the Pine Point Mine, an open-pit mine that produced lead and zinc ores. The town's population peaked at 1,915 in 1976, but was abandoned and deconstructed in 1988 after the mine closed in 1987.

Pine Point | |

|---|---|

Abandoned locality/former town | |

Pine Point, Northwest Territories, Canada | |

Pine Point  Pine Point | |

| Coordinates: 60°50′0″N 114°28′5″W / 60.83333°N 114.46806°W[1] | |

| Country | Canada |

| Territory | Northwest Territories |

| Region | South Slave Region |

| Census division | Region 5 |

| Constructed | 1962[2] |

| Incorporated (town) | April 1, 1974[3] |

| Dissolved | January 1, 1996[4] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unincorporated (previously mayor-council government) |

| • Final mayor | Michael Lenton[5] |

| Time zone | UTC−07:00 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

History edit

Construction of both the Pine Point mine and the community commenced in 1962.[2] Pine Point incorporated as a town on April 1, 1974.[3]

The mine was closed in 1987, forcing the single-industry town to close in 1988.[3] Mike Lenton was the town's last mayor.[5] Pine Point houses were sold cheaply, and many of the buildings were then moved to Fort Resolution (including the ice arena), Hay River and northern Alberta while the remaining buildings were demolished.[6] The Town of Pine Point was absorbed into Unorganized Fort Smith on January 1, 1996.[4] Today the site is completely abandoned, although there is still evidence of the street layout.[6]

Pine Point is the subject of Welcome to Pine Point, a 2011 web documentary created by Michael Simons and Paul Shoebridge and produced by the National Film Board of Canada.[7] The web documentary includes audiovisual material and mementos compiled by former resident Richard Cloutier for his own website, Pine Point Revisited.[8][9]

The song "Pine Point" by the Toronto, Ontario band PUP, is a non-fictional story about the town.

Demographics edit

As an unincorporated place, Pine Point's population was first recorded by Statistics Canada as 459 in 1966, an increase from a 1961 population of only 1.[10] It then grew to a population of 1,225 in the 1971 census.[11] By 1976, Pine Point held town status and reached a peak population of 1,915.[12] The town's population slightly declined to 1,861 by 1981[13] and then declined further to 1,558 by 1986.[14] The population exodus that followed closure of the mine left a population of only 9 in 1991.[13]

Education edit

Pine Point had two schools – Galena Heights Elementary School (grades K-6) and Matonabbee School (grades 7-12). Matonabbee School burned down on February 1, 1980, after which was replaced by a new building in the same location. The last graduating class was in 1988 after the mine's closure.

Places of worship edit

Transportation edit

Pine Point was along the Fort Resolution Highway,[1] and the Mackenzie Northern Railway, which was owned by the Canadian National Railway.[citation needed] Ore concentrates from the mine were moved south by the railroad.[citation needed] The town also had a small airport.[citation needed]

Notable people edit

- Everett Klippert,[18] last Canadian sent to jail for being gay

- Geoff Sanderson,[19] professional ice hockey player

Further reading edit

- Andersen Management Services Inc. (1987). Socio-economic impact assessment for the town of Pine Point, NWT. [s.l.]: Andersen Management Services.

- Deprez, P. (1973). The Pine Point Mine and the development of the area south of Great Slave Lake. Winnipeg: Center for Settlement Studies, University of Manitoba.

- Pine Point Mines Limited. (1978). Zinc/lead mining at Pine Point, N.W.T. Pine Point, N.W.T.: The Mines.

- Wilson, J., & Petruk, W. (1985). Quantitative mineralogy of Pine Point tailings. [Ottawa?]: CANMET, Energy, Mines and Resources Canada.

- Gibbins, W. (1988) Metallic mineral potential of the Western Interior Platform of the Northwest Territories. Geoscience Canada. Vol 15 NO. 2 pp 117–119

References edit

- ^ a b "Pine Point". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Bone, Robert M. (September 1988). "Resource Towns in the Mackenzie Basin" (PDF). Cahiers de Géographie du Québec. 42. University of Saskatchewan: Érudit: 249–259. doi:10.7202/022739ar. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ a b c "Gazetteer of the Northwest Territories". Northwest Territories Education, Culture and Employment. January 2017. p. 8. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ a b "Interim List of Changes to Municipal Boundaries, Status and Names: January 2, 1991 to January 1, 1996" (PDF). Statistics Canada. February 1997. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ a b "People_of_Pine_Point3". pinepointrevisited.homestead.com. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

- ^ a b Keeling, Arn; Sandlos, John (2012). Claiming the New North: Development and Colonialism at the Pine Point Mine, Northwest Territories, Canada (PDF). Faculty of Arts (Report). Memorial University of Newfoundland. ISSN 1752-7023.

- ^ Anderson, Kelly (26 January 2011). "NFB announces new web doc". Realscreen. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Quenneville, Guy (31 January 2011). "Remembering a lost mining town". Northern News Services. Archived from the original on 18 March 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ MacKie, John (14 April 2011). "Lost northern town is back, on the Net". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 31 May 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Population of unincorporated places of 50 persons and over, 1966 and 1961 (Alberta)". Census of Canada 1966: Population (PDF). Special Bulletin: Unincorporated Places. Vol. Bulletin S–3. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. August 1968. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ a b "Population of Unincorporated Places of 50 persons and over, 1971 and 1966 (Alberta)". 1971 Census of Canada: Population (PDF). Special Bulletin: Unincorporated Settlements. Vol. Bulletin SP—1. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. March 1973. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ a b "1976 Census of Canada: Population - Geographic Distributions" (PDF). Statistics Canada. June 1977. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c "1981 Census of Canada: Census subdivisions in decreasing population order" (PDF). Statistics Canada. May 1992. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "1986 Census: Population - Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions" (PDF). Statistics Canada. September 1987. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ "91 Census: Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions - Population and Dwelling Counts" (PDF). Statistics Canada. April 1992. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ a b "Photos_of_Pine4". pinepointrevisited.homestead.com. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

- ^ "People_of_Pine_Point8". pinepointrevisited.homestead.com. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

- ^ "Klippert v. The Queen". Supreme Court of Canada. November 7, 1967. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ "Hometown Sanderson". Sports Illustrated. October 28, 1999. Archived from the original on August 18, 2000. Retrieved April 5, 2013.