Summary

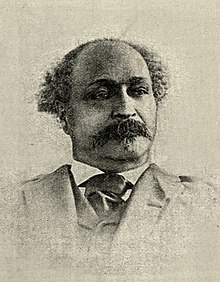

Primus Parsons Mason (February 5, 1817 – January 12, 1892) was an African-American entrepreneur, and real estate investor in Springfield, Massachusetts.[1] His parents, Jordan and Lurania Mason, were free people of color and Primus was one of seven children. Upon his death, a newspaper headline ("Our Aged Colored Citizen who Left most of Property for Charity") acknowledged his relative wealth and how he left most of his property or wealth to a charity organization he envisioned would be a home for aged men, in Springfield, Massachusetts.[1] He is the namesake for the city's Mason Square.

Primus Parsons Mason | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 5, 1817 |

| Died | January 12, 1892 (aged 74) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Teamster, prospector, real estate investor |

| Known for | Mason Square, benefactor of the Mason-Wright Retirement Community, underground railroad agent |

Early life edit

Mason was born on February 5, 1817, in Monson, Massachusetts, according to the Mason family's old Bible.[2] He received little formal education and was unable to write his own name until well past 40 years of age according to some accounts.[1][2] Paul R. Mason, a former Springfield City Councilman, is a relative of Mason.[3]

When Mason was seven years old his parents died and for five years he worked as an indentured servant to Jonathan Pomeroy of Suffield, Connecticut. According to W.E.B. Dubois, Mason was a farm hand. He ran away to Massachusetts and was apprenticed to a Monson farmer named Ferry. In 1837, Ferry's son severely beat Mason which led to his running away once again. Ferry may have enlisted his own son to beat Primus so as not to pay the $12 due Primus at the end of his service since, by running away, his contract as an indentured servant, would be void.[1]

At age 20, Mason escaped to the "Hayti" section of Springfield, Massachusetts.[a] He worked as a pig farmer, and managed to find "work as a teamster and [dead] horse undertaker". With the reliability of steady income through odd jobs such as collecting old shoe leather which he sold to the Springfield armory which was used to harden rifle barrels, and other menial tasks, Primus was able to make the first of many real estate investments. Daniel Charter, the seller of the property, in fact, loaned Mason the $50 to buy the property, which he paid back in full. The property was on the "north side of Boston Road" which today is in the Old Hill section of Springfield.

Career edit

The 1850 census listed Primus Mason as a farmer with real estate worth $1000 (~$28,435 in 2023). While other Black freemen in Springfield, such as Thomas Thomas, became involved in the city's underground abolitionist movement, Primus Mason was also a key player in the collective movement. A Springfield newspaper commented: "In abolition days, Primus Mason was one of the useful underground railway agents, receiving notice from Hartford allies when an escaping slave was on the road to this city and conveying the information to the Rev. Dr. Osgood, who looked out for the entertainment of the fugitive and sent him on toward Canada." However, he is most known and celebrated for his energetic business acumen, acquiring real estate (including undeveloped property in the Hill section which later became the McKnight neighborhood). Both Mason and Thomas Thomas ventured out west during the California's Gold Rush. Both men eventually returned to Springfield, Massachusetts a few years later. While away, his wife Lucretia died. The Springfield Republican wrote: "He returned to Springfield without money, but with a decided experience in favor of consecutive enterprises, and his business life then forward illustrated what can be achieved by industry, prudence, foresight, and judicious investment in real estate."

Census records of 1860 reveal that 276 Blacks lived in Springfield. Du Bois also observed that Mason "had a sense of industry, prudence, foresight" which enabled him to succeed. Mason was "shrewd but honest, as his means enabled him". By 1888 (at age 71), was one of the wealthiest citizens of Springfield. Primus Mason and his family lived on State Street in Springfield. A nearby street would eventually be named in his honor. He is reported to have had numerous wives, all of which he outlived. Only one daughter, Emily, resulted from these various unions. However, in 1873, at age thirty-four, she died childless.

Later life and legacy edit

In 1888, Primus suffered a setback when his barn was set on fire with in a blaze that grew beyond the scope of what the fire department was able to handle. Even with the loss of the property, Primus was able to save three horses, two cows, six carriages. He had insurance. The local paper reported that William Sharp was to be tried in court for setting the fire but, apparently, there was a hung jury and the case was dismissed.

In his book Efforts for Social Betterment Among Negro Americans (1909) DuBois notes "Few races are among instructively philanthropic than the Negro. It is shown in everyday life and in their group history". DuBois goes on to discuss Mason as one such individual. Primus Parson Mason was "one of the chief Negro Philanthropists of our time" which served Springfield, Massachusetts, a community that was home to both Mason and his extended family. Mason is quoted as saying he wanted to leave behind "a place where old men that are worthy may feel at home".[2]

Upon Mason's death on January 12, 1892, his estate funded a Springfield Home for Aged Men which continues today under the name Mason Wright Foundation. DuBois notes "[that] the foundation for a charity like this has been laid by one man, demands that some notice of his life be placed among our records".[2] At the time of his death, Mason has real estate property valued at $23,400, his net value being $29,451. His death notice in the paper stated: "It was a surprise to everybody that Primus Mason, who died last week, left a property, mostly in real estate, worth some $40,000. It notes that in addition to finding a home for aged men, he left $2000 (~$3,539 in 2023) to the Union Relief fund for aged couples". That same article offers Mason the dubious honor of being a reliable businessman, "industrious and thrifty when so many were idle and slack, temperate and honest, but shrewd and calculating". It is written he quietly paid "many a poor colored man's funeral expenses". While it is suggested he was married more than once, his latter years, it is claimed, were lonely, "without intimates of his own family". It is this last sentiment that perhaps led to his desire and self-appointed duty to found "a place…for worthy old men may feel at home". The home for aged man was open to any race since Mason "made no discrimination in race or color in this his principal charity". Today, the Mason Wright Foundation stands as the successor organization to the original trust, in the spirit of Primus Mason's will they note on their website "Our mission is to provide quality housing and daily living services to support the dignity and independence of seniors without regard for their ability to pay." Today the foundation maintains a four-acre independent and assisted living campus, Mason Wright Senior Living, with 118 apartments, as well as a homecare service, Colony Care at Home, and a child care center, Bright Futures Early Learning Center that provides intergenerational activities for the residents of Mason Wright. Primus Mason's legacy has grown to become an organization with 200 employees serving more than 700 seniors and children each week.[citation needed] In 2019, the Foundation dedicated a memorial park to Primus Mason at the corner of Oak and Walnut Streets in Springfield.[5]

Notes edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d "Primus P. Mason". Gold Rush Stories: The Pioneer Valley and the California Gold Rush. September 27, 2009. Springfield Benefactor, Courtesy of Museum of Springfield (MA) History

- ^ a b c d W. E. B. Du Bois (1909). Efforts for Social Betterment Among Negro Americans. Atlanta, Ga., The Atlanta University Press.

- ^ Joseph Carvalho III (2011). Black Families in Hampden County, Massachusetts 1650–1865 (Second ed.). New England Historic Genealogical Society.

- ^ Davis-Harris, Jeanette G (1982). Springfield's Ethnic Heritage: The Black Community. Bicentennial Committee of Springfield. p. 6.

- ^ Dobbs, G. Michael (November 6, 2019). "Primus Mason honored with memorial park". The Reminder.

- "Our Plural History – Springfield, MA. Resisting Slavery: Primus Mason". Springfield Technical Community College. 2009. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- At the Crossroads: Springfield, Massachusetts 1636–1975.

- Jeanette G. Davis-Harris (1976). Springfield's Ethnic Heritage: The Black Community. An Interpretation of the Black History of Springfield, Massachusetts – from the mid 1600s through 1940. U.S.A. Bicentennial Committee of Springfield, Inc. p. 32.

- Frank Bauer (1975). At the crossroads: Springfield, Massachusetts, 1636–1975. Sprintfield, Mass.: U.S.A. Bicentennial Committee of Springfield..