Summary

The Qin dynasty (/tʃɪn/;[3][4] also Chin dynasty; Chinese: 秦朝) was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its origin in the state of Qin, a fief of the confederal Zhou dynasty which had endured for over five centuries—until 221 BC, when it assumed an imperial prerogative following its complete conquest of its rival states, a state of affairs that lasted until its collapse in 206 BC.[5] It was formally established after the conquests in 221 BC, when Ying Zheng, who had become king of the Qin state in 246, declared himself to be "Shi Huangdi", the first emperor.

Qin 秦 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 221 BC–206 BC | |||||||||||||||

Territories of the Qin Empire. | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Xianyang | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Chinese | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||

• 221–210 BC | Qin Shi Huang | ||||||||||||||

• 210–207 BC | Qin Er Shi | ||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | |||||||||||||||

• 221–208 BC | Li Si | ||||||||||||||

• 208–207 BC | Zhao Gao | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Imperial | ||||||||||||||

• Accession of Qin Shi Huang | 221 BC | ||||||||||||||

• Death of Qin Shi Huang | 210 BC | ||||||||||||||

• Surrender to Liu Bang | 206 BC | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 220 BC[2] | 2,300,000 km2 (890,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Ban Liang | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | China | ||||||||||||||

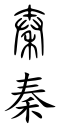

| Qin dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Qin" in seal script (top) and regular (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 秦 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Qín | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Qin was a minor power for the early centuries of its existence. The strength of the Qin state was greatly increased by the reforms of Shang Yang in the fourth century BC, during the Warring States period. In the mid and late third century BC, the Qin state carried out a series of swift conquests, destroying the powerless Zhou dynasty and eventually conquering the other six of the Seven Warring States. Its 15-year duration was the shortest major dynasty in Chinese history, with only two emperors. Despite its short existence, the legacy of Qin strategies in military and administrative affairs shaped the consummate Han dynasty that followed, ultimately becoming seen as the originator of an imperial system that lasted from 221 BC—with interruption, evolution, and adaptation—through to the Xinhai Revolution in 1912.[a]

The Qin sought to create a state unified by structured centralized political power and a large military supported by a stable economy.[6] The central government moved to undercut aristocrats and landowners to gain direct administrative control over the peasantry, who comprised the overwhelming majority of the population and labour force. This allowed ambitious projects involving three hundred thousand peasants and convicts: projects such as connecting walls along the northern border, eventually developing into the Great Wall of China, and a massive new national road system, as well as the city-sized Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor guarded by the life-sized Terracotta Army.[7]

The Qin introduced a range of reforms such as standardized currency, weights, measures and a uniform system of writing, which aimed to unify the state and promote commerce. Additionally, its military used the most recent weaponry, transportation and tactics, though the government was heavy-handed and bureaucratic. Qin created a system of administering people and land that greatly increased the power of the government to transform environment, and it has been argued that the subsequent impact of this system on East Asia's environments makes the rise of Qin an important event in China's environmental history.

When the first emperor died in 210 BC, two of his advisors placed an heir on the throne in an attempt to influence and control the administration of the dynasty. These advisors squabbled among themselves, resulting in both of their deaths and that of the second Qin Emperor. Popular revolt broke out and the weakened empire soon fell to a Chu general, Xiang Yu, who was proclaimed Hegemon-King of Western Chu, and Liu Bang, who founded the Han dynasty. Han Confucians portrayed the Qin dynasty as a monolithic, legalist tyranny, notably citing a purge known as the burning of books and burying of scholars. But its account first appears in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian. Some modern scholars dispute its veracity.[8]

History edit

Origins and early development edit

According to the Records of the Grand Historian, in the 9th century BC, Feizi, a supposed descendant of the ancient political advisor Gao Yao, was granted rule over the settlement of Qin (秦邑) in present-day Qingshui County of Shaanxi. During the rule of King Xiao of Zhou, the eighth king of the Zhou dynasty, this area became known as the state of Qin. In 897 BC, under the Gonghe Regency, the area became a dependency allotted for the purpose of raising and breeding horses.[9] One of Feizi's descendants, Duke Zhuang, became favoured by King Ping of Zhou, the 13th king in that line. As a reward, Zhuang's son, Duke Xiang, was sent eastward as the leader of a war expedition, during which he formally established the Qin.[10]

The state of Qin first began a military expedition into central China in 672 BC, though it did not engage in any serious incursions due to the threat from neighbouring tribesmen. By the dawn of the fourth century BC, however, the neighbouring tribes had all been either subdued or conquered, and the stage was set for the rise of Qin expansionism.[11]

Growth of power edit

Lord Shang Yang, a Qin statesman of the Warring States period, introducing a number of militarily advantageous reforms from 361 BC until his death in 338 BC. Yang also helped construct the Qin capital, commencing in the mid-fourth century BC Xianyang. The resulting city greatly resembled the capitals of other Warring States.[12]

Notably, Qin engaged in practical and ruthless warfare. During the Spring and Autumn period,[13] the prevalent philosophy had dictated war as a gentleman's activity; military commanders were instructed to respect what they perceived to be Heaven's laws in battle. For example, when Duke Xiang of the rival state of Song was at war with the state of Chu during the Warring States period, he declined an opportunity to attack the enemy force, commanded by Zhu, while they were crossing a river. After allowing them to cross and marshal their forces, he was decisively defeated in the ensuing battle. When his advisors later admonished him for such excessive courtesy to the enemy, he retorted, "The sage does not crush the feeble, nor give the order for attack until the enemy have formed their ranks."[14]

The Qin disregarded this military tradition, taking advantage of their enemy's weaknesses. A nobleman in the state of Wei accused the Qin state of being "avaricious, perverse, eager for profit, and without sincerity. It knows nothing about etiquette, proper relationships, and virtuous conduct, and if there be an opportunity for material gain, it will disregard its relatives as if they were animals."[15] This, combined with a strong leadership from long-lived rulers, openness to employ talented men from other states, and little internal opposition gave the Qin a strong political base.[16]

Another advantage of the Qin was that they had a large, efficient army and capable generals. They utilised the newest developments in weaponry and transportation as well, which many of their enemies lacked. These latter developments allowed greater mobility over several different terrain types which were most common in many regions of China. Thus, in both ideology and practice, the Qin were militarily superior.[17]

Finally, the Qin Empire had a geographical advantage due to its fertility and strategic position, protected by mountains that made the state a natural stronghold. This was the heart of the Guanzhong region, as opposed to the Yangtze River drainage basin, known as Guandong. The warlike nature of the Qin in Guanzhong inspired a Han dynasty adage: "Guanzhong produces generals, while Guandong produces ministers."[9] Its expanded agricultural output helped sustain Qin's large army with food and natural resources;[16] the Wei River canal built in 246 BC was particularly significant in this respect.[18]

Conquest of the Warring States edit

During the Warring States period preceding the Qin dynasty, the major states vying for dominance were Yan, Zhao, Qi, Chu, Han, Wei and Qin. The rulers of these states styled themselves as kings, rather than using the titles of lower nobility they had previously held. However, none elevated himself to believe that he had the "Mandate of Heaven", as the Zhou kings had claimed, nor that he had the right to offer sacrifices—they left this to the Zhou rulers.[19]

Before their conquest in the fourth and third centuries BC, the Qin suffered several setbacks. Shang Yang was executed in 338 BC by King Huiwen due to a personal grudge harboured from his youth. There was also internal strife over the Qin succession in 307 BC, which decentralised Qin authority somewhat. Qin was defeated by an alliance of the other states in 295 BC, and shortly after suffered another defeat by the state of Zhao, because the majority of their army was then defending against the Qi. The aggressive statesman Fan Sui (范雎), however, soon came to power as prime minister even as the problem of the succession was resolved, and he began an expansionist policy that had originated in Jin and Qi, which prompted the Qin to attempt to conquer the other states.[20]

The Qin were swift in their assault on the other states. They first attacked the Han, directly east, and took their capital city of Xinzheng in 230 BC. They then struck northward; the state of Zhao surrendered in 228 BC, and the northernmost state of Yan followed, falling in 226 BC. Next, Qin armies launched assaults to the east, and later the south as well; they took the Wei city of Daliang (now called Kaifeng) in 225 BC and forced the Chu to surrender by 223 BC. Lastly, they deposed the Zhou dynasty's remnants in Luoyang and conquered the Qi, taking the city of Linzi in 221 BC.[21]

When the conquests were complete in 221 BC, King Zheng – who had first assumed the throne of the Qin state at age 9[22] – became the effective ruler of China.[23] The subjugation of the six states was done by King Zheng who had used efficient persuasion and exemplary strategy. He solidified his position as sole ruler with the abdication of his prime minister, Lü Buwei. The states made by the emperor were assigned to officials dedicated to the task rather than place the burden on people from the royal family.[23] He then combined the titles of the earlier Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors into his new name: Shi Huangdi (始皇帝) or "First Emperor".[24] The newly declared emperor ordered all weapons not in the possession of the Qin to be confiscated and melted down. The resulting metal was sufficient to build twelve large ornamental statues at the Qin's newly declared capital, Xianyang.[25]

Southward expansion edit

In 214 BC, Qin Shi Huang secured his boundaries to the north with a fraction (100,000 men) of his large army, and sent the majority (500,000 men) of his army south to conquer the territory of the southern tribes. Prior to the events leading to Qin dominance over China, they had gained possession of much of Sichuan to the southwest. The Qin army was unfamiliar with the jungle terrain, and it was defeated by the southern tribes' guerrilla warfare tactics with over 100,000 men lost. However, in the defeat Qin was successful in building a canal to the south, which they used heavily for supplying and reinforcing their troops during their second attack to the south. Building on these gains, the Qin armies conquered the coastal lands surrounding Guangzhou, and took the provinces of Fuzhou and Guilin. They may have struck as far south as Hanoi. After these victories in the south, Qin Shi Huang moved over 100,000 prisoners and exiles to colonize the newly conquered area. In terms of extending the boundaries of his empire, the First Emperor was extremely successful in the south.[25]

Campaigns against the Xiongnu edit

However, while the empire at times was extended to the north, the Qin could rarely hold on to the land for long. The tribes of these locations, collectively called the Hu by the Qin, were free from Chinese rule during the majority of the dynasty.[26] Prohibited from trading with Qin dynasty peasants, the Xiongnu tribe living in the Ordos region in northwest China often raided them instead, prompting the Qin to retaliate. After a military campaign led by General Meng Tian, the region was conquered in 215 BC and agriculture was established; the peasants, however, were discontented and later revolted. The succeeding Han dynasty also expanded into the Ordos due to overpopulation, but depleted their resources in the process. Indeed, this was true of the dynasty's borders in multiple directions; modern Xinjiang, Tibet, Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, and regions to the southeast were foreign to the Qin, and even areas over which they had military control were culturally distinct.[27]

Fall from power edit

Three assassination attempts were made on Qin Shi Huang,[28] leading him to become paranoid and obsessed with immortality. He died in 210 BC, while on a trip to the far eastern reaches of his empire in an attempt to procure an elixir of immortality from Taoist magicians, who claimed the elixir was stuck on an island guarded by a sea monster. The chief eunuch, Zhao Gao, and the prime minister, Li Si, hid the news of his death upon their return until they were able to alter his will to place on the throne the dead emperor's most pliable son, Huhai, who took the name of Qin Er Shi.[22] They believed that they would be able to manipulate him to their own ends, and thus effectively control the empire. Qin Er Shi was, indeed, inept and pliable. He executed many ministers and imperial princes, continued massive building projects (one of his most extravagant projects was lacquering the city walls), enlarged the army, increased taxes, and arrested messengers who brought him bad news. As a result, men from all over China revolted, attacking officials, raising armies, and declaring themselves kings of seized territories.[29]

During this time, Li Si and Zhao Gao fell out, and Li Si was executed. Zhao Gao decided to force Qin Er Shi to commit suicide due to Qin Er Shi's incompetence. Upon this, Ziying, a nephew of Qin Er Shi, ascended the throne, and immediately executed Zhao Gao.[29] Ziying, seeing that increasing unrest was growing among the people[note 1] and that many local officials had declared themselves kings, attempted to cling to his throne by declaring himself one king among all the others.[18] He was undermined by his ineptitude, however, and popular revolt broke out in 209 BC. When Chu rebels under the lieutenant Liu Bang attacked, a state in such turmoil could not hold for long. Ziying was defeated near the Wei River in 207 BC and surrendered shortly after; he was executed by the Chu leader Xiang Yu. The Qin capital was destroyed the next year, and this is considered by historians to be the end of the Qin Empire.[30][note 2] Liu Bang then betrayed and defeated Xiang Yu, declaring himself Emperor Gaozu[note 3] of the new Han dynasty on 28 February 202 BC.[31] Despite the short duration of the Qin dynasty, it was very influential on the structure of future dynasties.

Culture and society edit

Domestic life edit

The aristocracy of the Qin were largely similar in their culture and daily life. Regional variations in culture were considered a symbol of the lower classes. This stemmed from the Zhou and was seized upon by the Qin, as such variations were seen as contrary to the unification that the government strove to achieve.[32]

Commoners and rural villagers, who made up over 90% of the population,[33] very rarely left the villages or farmsteads where they were born. Forms of employment differed by region, though farming was almost universally common. Professions were hereditary; a father's employment was passed to his eldest son after he died.[34] The Lüshi Chunqiu[note 4] gave examples of how, when commoners are obsessed with material wealth, instead of the idealism of a man who "makes things serve him", they were "reduced to the service of things".[35]

Peasants were rarely figured in literature during the Qin dynasty and afterwards; scholars and others of more elite status preferred the excitement of cities and the lure of politics. One notable exception to this was Shen Nong, the so-called "Divine Father", who taught that households should grow their own food. "If in one's prime he does not plow, someone in the world will grow hungry. If in one's prime she does not weave, someone in the world will be cold." The Qin encouraged this; a ritual was performed once every few years that consisted of important government officials taking turns with the plow on a special field, to create a simulation of government interest and activity within agriculture.[34]

Architecture edit

Warring States-era architecture had several definitive aspects. City walls, used for defense, were made longer, and indeed several secondary walls were also sometimes built to separate the different districts. Versatility in federal structures was emphasized, to create a sense of authority and absolute power. Architectural elements such as high towers, pillar gates, terraces, and high buildings amply conveyed this.[36]

Philosophy and literature edit

The written language of the Qin was logographic, as that of the Zhou had been.[37] As one of his most influential achievements in life, prime minister Li Si standardized the writing system to be of uniform size and shape across the whole country. This would have a unifying effect on the Chinese culture for thousands of years. He is also credited with creating the "small seal script" (Chinese: 小篆,; pinyin: xiǎozhuàn) style of calligraphy, which serves as a basis for modern Chinese and is still used in cards, posters, and advertising.[38]

During the Warring States period, the Hundred Schools of Thought comprised many different philosophies proposed by Chinese scholars. Contemporary institutions descended in part from the methods of the Mohists and school of names.[39]: 141–144 Confucius's school of thought, called Confucianism, was also influential beginning in the Warring States period, and throughout the imperial periods.[note 5] Beginning in the subsequent Han dynasty, this school of thought had a so-called Confucian canon of literature, known as the "six classics": the Odes, Documents, Ritual, Music, Spring and Autumn Annals, and Changes, which embodied Chinese literature at the time.[40]

Penal policy edit

The Qin empire's laws were primarily administrative. Only including penal law alongside li ritual, comparative model manuals in the Qin empire guided penal legal procedure and application based on real-life situations, with publicly named wrongs linked to punishments.

While some Qin penal laws deal with infanticide or other unsanctioned harm of children, it primarily concerned theft; it does not much deal with murder, as either more straightforward or more suitable to ritual. By contrast, detailed rules and "endless paperwork" tightly regulate grain, weights, measures, and official documents.[41] Like most ancient societies, tradition China did not divide administration and judiciary,[42] but it did include such concepts as intent, judicial procedure, defendant rights, retrial requests and distinctions between different kinds of law (common law and statutory law).[43]

The Book of Lord Shang prophecies a future sage of "benevolence and righteous",[44] which the First Emperor declares himself to be.[45] Regardless, in the Qin and early Han, criminals may be given amnesties, and then only punished if they did it again.[46]

At the very least given Qin expansionism, penal law actually develops more in the Han dynasty. The Qin often expelled criminals to the new colonies, or pardoned them in exchange for fines, labor, or one to several aristocratic ranks, even up to the death penalty. While the penal laws would still be considered harsh compared to the modern day, they were not very harsh for their time, and often not actually enacted.[47]

Villainizing the first Emperor while adopting Qin administration,[48] a confused revulsion against the Qin occurs in the Han dynasty, centering on Shang Yang and Han Fei as espousing rigorous law and punishment. The Qin dynasty would be classically taken as having practiced these.[49] Whatever events may have transpired, while Shang Yang and Han Fei may have been influential in Qin administration, Qin archaeology finds the Qin to have abandoned the harsh penal policy of Shang Yang before its founding.[50]

Government and military edit

The Qin government was highly bureaucratic, and was administered by a hierarchy of officials, all serving the First Emperor. The Qin put into practice the teachings of Han Feizi, allowing the First Emperor to control all of his territories, including those recently conquered. All aspects of life were standardized, from measurements and language to more practical details, such as the length of chariot axles.[24]

The states made by the emperor were assigned to officials dedicated to the task rather than placing the burden on people from the royal family. Zheng and his advisors also introduced new laws and practices that ended feudalism in China, replacing it with a centralized, bureaucratic government. A supervisory system, the Censorate was introduced to monitor and check the powers of administrators and officials at each level of government.[51]

The form of government created by the first emperor and his advisors was used by later dynasties to structure their own government.[23] Under this system, both the military and government thrived, as talented individuals could be more easily identified in the transformed society. Later Chinese dynasties emulated the Qin government for its efficiency, despite its being condemned by Confucian philosophy.[24][52] There were instances of abuse, however, with one example having been recorded in the "Records of Officialdom". A commander named Hu ordered his men to attack peasants in an attempt to increase the number of "bandits" he had killed; his superiors, likely eager to inflate their records as well, allowed this.[53]

Qin Shi Huang also improved the strong military, despite the fact that it had already undergone extensive reforms.[54] The military used the most advanced weaponry of the time. It was first used mostly in bronze form, but by the third century BC, kingdoms such as Chu and Qin were using iron and/or steel swords. The demand for this metal resulted in improved bellows. The crossbow had been introduced in the fifth century BC and was more powerful and accurate than the composite bows used earlier. It could also be rendered ineffective by removing two pins, which prevented enemies from capturing a working crossbow.[55]

The Qin also used improved methods of transportation and tactics. The state of Zhao had first replaced chariots with cavalry in 307 BC, but the change was swiftly adopted by the other states because cavalry had greater mobility over the terrain of China.[56]

The First Emperor developed plans to fortify his northern border, to protect against nomadic invasions. The result was the initial construction of what later became the Great Wall of China, which was built by joining and strengthening the walls made by the feudal lords, which would be expanded and rebuilt multiple times by later dynasties, also in response to threats from the north. Another project built during Qin Shi Huang's rule was the Terracotta army, intended to protect the emperor after his death.[54] The Terracotta Army was inconspicuous due to its underground location, and was not discovered until 1974.[57]

Religion edit

Floating on high in every direction,

Music fills the hall and court.

The incense sticks are a forest of feathers,

The cloudy scene an obscure darkness.

Metal stalks with elegant blossoms,

A host of flags and kingfisher banners.

The music of the "Seven Origins" and "Blossoming Origins"

Are intoned as harmonious sounds.

Thus one can almost hear

The spirits coming to feast and frolic.

The spirits are seen off to the zhu zhu of the musics,

Which purifies and refines human feelings.

Suddenly the spirits ride off on the darkness,

And the brilliant event finishes.

Purified thoughts grow hidden and still,

And the warp and weft of the world fall dark.

Han shu, p. 1046

The dominant religious belief in China during the reign of the Qin, and, in fact, during much of early imperial China, was focused on the shen (roughly translating to "spirits" or "gods"), yin ("shadows"), and the realm they were said to live in. The Chinese offered animal sacrifices in an attempt to contact this other world, which they believed to be parallel to the earthly one. The dead were said to have simply moved from one world to the other. The rituals mentioned, as well as others, served two purposes: to ensure that the dead journeyed and stayed in the other realm, and to receive blessings from the spirit realm.[note 6][58][59]

Religious practices were usually held in local shrines and sacred areas, which contained sacrificial altars. During a sacrifice or other ritual, the senses of all participants and witnesses would be dulled and blurred with smoke, incense, and music. The lead sacrificer would fast and meditate before a sacrifice to further blur his senses and increase the likelihood of perceiving otherworldly phenomena. Other participants were similarly prepared, though not as rigorously.

Such blurring of the senses was also a factor in the practice of spirit intermediaries, or mediumship. Practitioners of the art would fall into trances or dance to perform supernatural tasks. These people would often rise to power as a result of their art—Luan Da, a Han dynasty medium, was granted rule over 2,000 households. Noted Han historian Sima Qian was scornful of such practices, dismissing them as foolish trickery.[60]

Divination—to predict and/or influence the future—was yet another form of religious practice. An ancient practice that was common during the Qin dynasty was cracking bones or turtle shells to gain knowledge of the future. The forms of divination which sprang up during early imperial China were diverse, though observing natural phenomena was a common method. Comets, eclipses, and droughts were considered omens of things to come.[61]

Etymology of China edit

The name 'Qin' is believed to be the etymological ancestor of the modern-day European name of the country, China. The word probably made its way into the Indo-Aryan languages first as 'Cina' or 'Sina' and then into Greek and Latin as 'Sinai' or 'Thinai'. It was then transliterated into English and French as 'China' and 'Chine'. This etymology is dismissed by some scholars, who suggest that 'Sina' in Sanskrit evolved much earlier before the Qin dynasty. However, the preceding state of Qin was itself founded in the 9th century BCE. 'Jin', a state during the Zhou dynasty until the fourth century BC, is another possible origin.[65] Others argued for the state of Jing (荆, another name for Chu), as well as other polities in the early period as the source of the name.[66]

Sovereigns edit

Qin Shi Huang was the first Chinese sovereign to proclaim himself "Emperor", after unifying China in 221 BC. That year is therefore generally taken by historians to be the start of the "Qin dynasty" which lasted for fifteen years until 207 when it was cut short by civil wars.[67]

| Posthumous name / title | Personal name | Period of Reigns |

|---|---|---|

| Shi Huangdi | Zheng (政) | 221 – 210 BC |

| Er Shi Huangdi | Huhai (胡亥) | 210 – 207 BC |

| None | Ziying (子嬰) | 207 BC |

Imperial family tree edit

| Qin Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

'

Notes edit

- ^ This was largely caused by regional differences which survived despite the Qin's attempt to impose uniformity.

- ^ The first emperor of the Qin had boasted that the dynasty would last 10,000 generations; it lasted only about 15 years. (Morton 1995, p. 49)

- ^ Meaning "High Progenitor".

- ^ A text named for its sponsor Lü Buwei; the prime minister of the Qin directly preceding the conquest of the other states.

- ^ The term "Confucian" is rather ill-defined in this context—many self-dubbed Confucians in fact rejected tenets of what was known as "the Way of Confucius", and were disorganized, unlike the later Confucians of the Song and Yuan dynasties.

- ^ Mystics from the state of Qi, however, saw sacrifices differently—as a way to become immortal.

- ^ Notwithstanding the brief restoration in 1917.

References edit

Citations edit

- ^ a b c "Qin dynasty". Britannica. 3 September 2019.

- ^ Taagepera, Rein (1979). "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D". Social Science History. 3 (3/4): 121. doi:10.2307/1170959. JSTOR 1170959.

- ^ "Qin". Collins English Dictionary (13th ed.). HarperCollins. 2018. ISBN 978-0-008-28437-4.

- ^ "Qin". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins.

- ^ "...The collapse of the Western Zhou state in 771 BC and the lack of a true central authority thereafter opened ways to fierce inter-state warfare that continued over the next five hundred years until the Qin unification of China in 221 BC, thus giving China her first empire." Early China A Social and Cultural History, Cambridge University Press, 2013, page 6.

- ^ Tanner 2010, pp. 85–89

- ^ Beck, R B; Black, L; Krager, L S; et al. (2003). Ancient World History-Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: Mc Dougal Little. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-618-18393-7.

- ^ Lander, Brian (2021). The King's Harvest: A Political Ecology of China from the First Farmers to the First Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300255089.

- ^ a b Lewis 2007, p. 17

- ^ "Chinese surname history: Qin". People's Daily. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ Lewis 2007, pp. 17–18

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 88

- ^ Origins of Statecraft in China

- ^ Morton 1995, pg. 26,45

- ^ Time-Life Books 1993, p. 86

- ^ a b Kinney and Clark 2005, p. 10

- ^ Morton 1995, p. 45

- ^ a b Lewis 2007, pp. 18–19

- ^ Morton 1995, p. 25

- ^ Lewis 2007, pp. 38–39

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 10

- ^ a b Bai Yang. 中国帝王皇后亲王公主世系录 [Records of the Genealogy of Chinese Emperors, Empresses, and Their Descendants] (in Simplified Chinese). Vol. 1. Friendship Publishing Corporation of China (中国友谊出版公司). pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b c Loewe, Michael (9 September 2007). "China's First Empire". History Today. Vol. 57, no. 9. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ a b c World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia, p. 36

- ^ a b Morton 1995, p. 47

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 129

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 5

- ^ Borthwick, p. 10

- ^ a b Kinney and Hardy 2005, pp. 13–15

- ^ Bodde 1986, p. 84

- ^ Morton 1995, pp. 49–50

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 11

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 102

- ^ a b Lewis 2007, p. 15

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 16

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 75–78

- ^ World and its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia, p. 34

- ^ Bedini 1994, p. 83

- ^ Smith, Kidder (2003). "Sima Tan and the Invention of Daoism, 'Legalism,' et cetera". Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (1). Duke University Press: 129–156. doi:10.2307/3096138. JSTOR 3096138.

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 206

- ^ Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John K.; Loewe, Michael (26 December 1986). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD 220. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ^ Michael Loewe 1978/1986 528. The Cambridge History of China Volume I: Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. -- A.D. 220.

- ^ Goldin 2005. p5-6 After Confucius

- ^ Pines 2017. p84. Abridged Book of Lord Shang.

- ^ Pines 2014 Birth of an Empire. p267 https://books.google.com/books?id=_aowDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA267

- Pines 2013. p267. The Messianic Emperor

- ^ Pines 2014 Birth of an Empire. p213 https://books.google.com/books?id=_aowDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA213

- ^

- Michael Loewe 1978/1986 74,526,534-535. The Cambridge History of China Volume I: Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. -- A.D. 220.

- Goldin 2005. p5 After Confucius

- ^

- Mark Edward Lewis 2007. p42,72. The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han

- Pines 2009. p110. Envisioning Eternal Empire

- ^ Michael Loewe 1999 p1008, The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C

https://books.google.com/books?id=cHA7Ey0-pbEC&pg=PA1008

- Creel 1970 p92. What is Taoism?

- ^ Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2023/entries/chinese-legalism/

- ^ Xue, Deshu; Qi, Xiuqian. "Research on Supervision System in Ancient China and Its Contemporary Reference". Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. 319: 415.

- ^ Borthwick 2006, pp. 9–10

- ^ Chen, pp. 180–81

- ^ a b Borthwick 2006, p. 10

- ^ Morton 1995, p. 26

- ^ Morton 1995, p. 27

- ^ "Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 178

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 186

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 180

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 181

- ^ Coatsworth, John; Cole, Juan; Hanagan, Michael P.; Perdue, Peter C.; Tilly, Charles; Tilly, Louise (16 March 2015). Global Connections: Volume 1, To 1500: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-316-29777-3.

- ^ Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0.

- ^ Jeroen Van Den Bosch; Adrien Fauve; B. J. De Cordier, eds. (2021). The European Handbook of Central Asian Studies. Ibidem Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-3-8382-1518-1.

- ^ Keay 2009, p. 98.

- ^ Wade, Geoff (May 2009). "The Polity of Yelang and the Origin of the Name 'China'" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 188. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011. "This thesis also helps explain the existence of Cīna in the Indic Laws of Manu and the Mahabharata, likely dating well before Qin Shihuangdi."

- ^ Bodde 1986, p. 20

Sources edit

- World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia. Marshall Cavendish. 2007. ISBN 978-0-7614-7631-3.

- Philip J. Ivanhoe; Bryan W. Van Norden, eds. (2005). Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87220-780-6.

- Breslin, Thomas A. (2001). Beyond Pain: The Role of Pleasure and Culture in the Making of Foreign Affairs. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-97430-5.

- Bedini, Silvio (1994). The Trail of Time: Shih-chien Ti Tsu-chi : Time Measurement with Incense in East Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37482-8.

- Bodde, Derk (1986). "The State and Empire of Ch'in". In Twitchett, Dennis; Loewe, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC–AD 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Borthwick, Mark (2006). Pacific Century: The Emergence of Modern Pacific Asia. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4355-6.[permanent dead link]

- Kinney, Anne Behnke; Hardy, Grant (2005). The Establishment of the Han Empire and Imperial China. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32588-5.

- Keay, John (2009). China A History. Harper Press. ISBN 9780007221783.

- Lander, Brian (2021). The King's Harvest: A Political Ecology of China from the First Farmers to the First Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300255089.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007). The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. London: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02477-9.

- Chen Guidi; Wu Chuntao (2007). Will the Boat Sink the Water?: The Life of China's Peasants. Translated by Zhu Hong. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-441-5.

- Morton, W. Scott (1995). China: Its History and Culture (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-043424-0.

- Tanner, Harold (2010). China: A History. Hackett. ISBN 978-1-60384-203-7.

Further reading edit

- Bodde, Derk (1986). "The State and Empire of Ch'in". In Twitchett, Dennis; Loewe, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC–AD 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Lander, Brian (2021). The King's Harvest: A Political Ecology of China from the First Farmers to the First Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300255089.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007). The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. London: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02477-9.

- Korolkov, Maxim (2022). The Imperial Network in Ancient China: The Foundation of Sinitic Empire in Southern East Asia. Routledge. ISBN 9780367654283.

External links edit

- Media related to Qin Dynasty at Wikimedia Commons

![Heirloom Seal of the Realm of Qin, Ch'in[1] or Kin[1] dynasty](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/Inscription_on_Imperial_Seal_of_China_%22%E5%8F%97%E5%91%BD%E6%96%BC%E5%A4%A9_%E6%97%A2%E5%A3%BD%E6%B0%B8%E6%98%8C%22.svg/85px-Inscription_on_Imperial_Seal_of_China_%22%E5%8F%97%E5%91%BD%E6%96%BC%E5%A4%A9_%E6%97%A2%E5%A3%BD%E6%B0%B8%E6%98%8C%22.svg.png)