Summary

Quantitative tightening (QT) is a contractionary monetary policy tool applied by central banks to decrease the amount of liquidity or money supply in the economy. A central bank implements quantitative tightening by reducing the financial assets it holds on its balance sheet by selling them into the financial markets, which decreases asset prices and raises interest rates.[1] QT is the reverse of quantitative easing (or QE), where the central bank prints money and uses it to buy assets in order to raise asset prices and stimulate the economy. QT is rarely used by central banks, and has only been employed after prolonged periods of Greenspan put-type stimulus, where the creation of too much central banking liquidity has led to a risk of uncontrolled inflation (e.g. 2008, 2018 and 2022).[2][3]

Background edit

Quantitative easing was massively applied by leading central banks to counter the Great Recession that started in 2008.[3] The prime rates were decreased to zero; some rates later went into the negative territory. For example, to fight with ultra-low inflation or deflation caused by the economic crisis, the European Central Bank, overseeing monetary policy for countries that use the euro, introduced negative rates in 2014. The central banks of Japan, Denmark, Sweden, and Switzerland also set negative rates.[4]

The main goal of QT is to normalize (i.e. raise) interest rates in order to avoid increasing inflation, by increasing the cost of accessing money and reducing demand for goods and services in the economy. Like QE before it,[needs update] QT has never been done before on a massive scale, and its consequences have yet to materialize and be studied.[5] In 2018, the Federal Reserve began retiring some of the debt on its balance sheet, beginning quantitative tightening. In 2019, less than a year after initiating QT, central banks, including the Federal Reserve, ended quantitative tightening due to negative market conditions occurring soon after.[6]

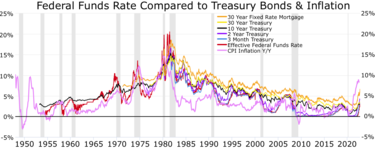

In December 2021, there were reports that Jerome Powell, chair of the Federal reserve, was under pressure to slow down QE and mortgage-backed security (MBS) purchases. This was due to severe inflation, with the CPI reading in November 2021 reaching a record-breaking 6.8% according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the highest level in 40 years.[7] Bloomberg News called Powell "Wall Street's Head of State", as a reflection of how dominant Powell's actions were on asset prices and how profitable his actions were for Wall Street.[8]

Effect on asset prices edit

Whereas QE caused the substantial rise in asset prices over the past decade, QT may cause broadly offsetting effects in the opposite direction.[9] To mitigate the financial market impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, Powell accepted asset price inflation as a consequence of Fed policy actions.[10][11] Powell was criticized for using high levels of direct and indirect quantitative easing as valuations hit levels last seen at the peaks of previous bubbles.[12][13]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Engemann, Kristie (July 17, 2019). "What Is Quantitative Tightening?". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

- ^ Brookes, Marcus (October 18, 2017). "60 seconds explaining quantitative tightening". Schroders. schroders.com. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ a b Phillips, Matt (30 January 2019). "The Hot Topic in Markets Right Now: 'Quantitative Tightening'". The New York Times.

- ^ Soble, Jonathan (September 20, 2016). "Japan's Negative Interest Rates Explained". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "What Is Quantitative Tightening?". FXCM. fxcm.com. 5 March 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Fed Move Ends the Short Era of Global Quantitative Tightening". Bloomberg. Bloomberg L.P. August 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "US price rises hit highest level for 40 years". BBC. December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Greifeld, Katherine; Wang, Lu; Hajric, Vildana (November 6, 2020). "Stocks Show Jerome Powell Is Still Wall Street's Head of State". Bloomberg News.

- ^ Webb, Merryn Somerset (23 April 2018). "What to do as quantitative easing becomes quantitative tightening". Money Week. moneyweek.com. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Quick Hits: Powell Isn't Worried Fed Actions Are Generating Asset Bubbles". The Wall Street Journal. September 16, 2020.

- ^ Mackenzie, Michael (13 June 2020). "Investors reset for Fed's single-minded pursuit of policy goals". Financial Times.

- ^ Lachman, Desmond (May 19, 2020). "The Federal Reserve's everything bubble". The Hill.

- ^ Randall, David (September 11, 2020). "Fed defends 'pedal to the metal' policy and is not fearful of asset bubbles ahead". Reuters.

External links edit

- BNP Paribas on Quantitative tightening

- Federal Reserve, USA