Summary

The rally 'round the flag effect (or syndrome) is a concept used in political science and international relations to explain increased short-run popular support of a country's government or political leaders during periods of international crisis or war.[1] Because the effect can reduce criticism of governmental policies, it can be seen as a factor of diversionary foreign policy.[1]

Mueller's definition edit

Political scientist John Mueller suggested the effect in 1970, in a paper called "Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson". He defined it as coming from an event with three qualities:[2]

- "Is international"

- "Involves the United States and particularly the President directly"

- "Specific, dramatic, and sharply focused"

It is worth noting that quality 2, as well as other aspects, are redundant as this phenomenon is seen beyond America, such as the 2023 Hamas-led attack on Israel temporarily uniting a Benjamin Netanyahu led coalition government.

In addition, Mueller created five categories of rallies. Mueller's five categories are:

- Sudden US military intervention (e.g., Korean War, Bay of Pigs Invasion)

- Major diplomatic actions (e.g., Truman Doctrine)

- Dramatic technological developments (e.g., Sputnik)

- US-Soviet summit meetings (e.g., Potsdam Conference)

- Major military developments in ongoing wars (e.g., Tet Offensive)

These categories are considered dated by modern political scientists, as they rely heavily on Cold War events.[3]

Causes and duration edit

Since Mueller's original theories, two schools of thought have emerged to explain the causes of the effect. The first, "The Patriotism School of Thought" holds that in times of crisis, the American public sees the President as the embodiment of national unity. The second, "The Opinion Leadership School" believes that the rally emerges from a lack of criticism from members of the opposition party, most often in the United States Congress. If opposition party members appear to support the president, the media has no conflict to report, thus it appears to the public that all is well with the performance of the president.[4] The two theories have both been criticized, but it is generally accepted that the Patriotism School of thought is better to explain causes of rallies, while the Opinion Leadership School of thought is better to explain duration of rallies.[3] It is also believed that the lower the presidential approval rating before the crisis, the larger the increase will be in terms of percentage points because it leaves the president more room for improvement. For example, Franklin D. Roosevelt only had a 12pp increase in approval from 72% to 84% following the Attack on Pearl Harbor, whereas George W. Bush had a 39pp increase from 51% to 90% following the September 11 attacks.[5]

Another theory about the cause of the effect is believed to be embedded in the US Constitution. Unlike in other countries, the constitution makes the President both head of government and head of state. Because of this, the president receives a temporary boost in popularity because his Head of State role gives him symbolic importance to the American people. However, as time goes on his duties as Head of Government require partisan decisions that polarize opposition parties and diminish popularity. This theory falls in line more with the Opinion Leadership School.

Due to the highly statistical nature of presidential polls, University of Alabama political scientist John O'Neal has approached the study of rally 'round the flag using mathematics. O'Neal has postulated that the Opinion Leadership School is the more accurate of the two using mathematical equations. These equations are based on quantified factors such as the number of headlines from The New York Times about the crisis, the presence of bipartisan support or hostility, and prior popularity of the president.[6]

Political Scientist from The University of California Los Angeles, Matthew A. Baum found that the source of a rally 'round the flag effect is from independents and members of the opposition party shifting their support behind the President after the rallying effect. Baum also found that when the country is more divided or in a worse economic state then the rally effect is larger. This is because more people who are against the president before the rallying event switch to support him afterwards. When the country is divided before the rallying event there is a higher potential increase in support for the President after the rallying event.[7]

In a study by Political Scientist Terrence L. Chapman and Dan Reiter, rallies in Presidential approval ratings were found to be bigger when there was U.N. Security Council supported Militarized interstate disputes (MIDs). Having U.N. Security Council support was found to increase the rally effect in presidential approval by 8 to 9 points compared to when there was not U.N. Security Council support.[5]

According to a 2019 study of ten countries in the period 1990–2014, there is evidence of a rally-around-the-flag effect early on in an intervention with military casualties (in at least the first year) but voters begin to punish the governing parties after 4.5 years.[8] A 2021 study found weak effects for the rally-around-the-flag effect.[9] A 2023 study found that militarized interstate disputes, on average, decrease public support for national leaders rather than increase it.[10]

A 2022 study applies the same logic of rally effects to crisis termination instead of just onset. Using all available public presidential polling and crisis data from 1953 to 2016, the researchers found that a president received a three point increase to their approval rating, on average, when terminating an international crisis. They suggest that the surge in approvals is as much related to a proof of a president's foreign affairs competency, as it is related to a mutual camaraderie in defense of the nation.[11] Additionally, the suggestion that a president can achieve approval boosts via ending conflict instead of initiating conflict makes less cynical assumptions about the options within a president's toolkit and provide an additional avenue for inquiry into diversionary war theories.

Historical examples edit

The effect has been examined within the context of nearly every major foreign policy crisis since World War II. Some notable examples:

United States edit

- Cuban Missile Crisis: According to Gallup polls, President John F. Kennedy's approval rating in early October 1962 was at 61%. By November, after the crisis had passed, Kennedy's approval rose to 74%. The spike in approval peaked in December 1962 at 76%. Kennedy's approval rating slowly decreased again until it reached the pre-crisis level of 61% in June 1963.[3][12]

- Iran hostage crisis: According to Gallup polls, President Jimmy Carter quickly gained 26 percentage points, jumping from 32 to 58% approval following the initial seizure of the U.S. embassy in Tehran in November 1979. However, Carter's handling of the crisis caused popular support to decrease, and by November 1980 Carter had returned to his pre-crisis approval rating.[13]

- Operation Desert Storm (Persian Gulf War): According to Gallup polls, President George H. W. Bush was rated at 59% approval in January 1991, but following the success of Operation Desert Storm, Bush enjoyed a peak 89% approval rating in February 1991. From there, Bush's approval rating slowly decreased, reaching the pre-crisis level of 61% in October 1991.[3][14]

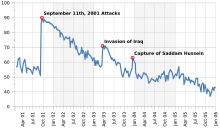

- Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, President George W. Bush received an unprecedented increase in his approval rating. On September 10, Bush had a Gallup Poll rating of 51%. By September 15, his approval rate had increased by 34 percentage points to 85%. Just a week later, Bush was at 90%, the highest presidential approval rating ever. Over a year after the attacks occurred, Bush still received higher approval than he did before 9/11 (68% in November 2002). Both the size and duration of Bush's popularity after 9/11 are believed to be the largest of any post-crisis boost. Many people believe that this popularity gave Bush a mandate and eventually the political leverage to begin the War in Iraq.[3][15]

- Death of Osama bin Laden: According to Gallup polls, President Barack Obama received a 6% jump in his Presidential approving ratings, jumping from 46% in the three days before the mission (April 29 – May 1) to a 52% in the 3 days after the mission (May 2–4).[16] The rally effect did not last long, as Obama's approval ratings were back down to 46% by June 30.

World War I edit

- During World War I, most belligerents saw a lessening of partisanship. Most socialist parties abandoned their pledges to oppose wars and endorsed their governments, leading to the break-up of the Second International.[17]

- In the German Empire, the Social Democratic Party enabled the German entry into the war by voting in favor of war credits at the Reichstag and supported the government for most of the war. Kaiser Wilhelm II subsequently declared a Burgfrieden in which normal partisan politics would be suspended.[18][19][20]

- The French Third Republic declared a similar Union sacree which was embraced by most socialist parties. The French Section of the Workers' International leader Jean Jaurès was assassinated while preparing to give what the French nationalist assassin Raoul Villain believed would be a pacifist speech.[18][21]

- The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland also saw a lessening of political instability and militancy as Irish nationalist, suffragette, and trade unionist dissidents supported the war.[18] In particular the Curragh mutiny, in which many Ulster Protestants and some officers of the British Armed Forces with the support of the Conservative Party refused to recognize the impending implementation of Irish Home Rule and threatened civil war, immediately ended with the British entry into the war and an upswell of support for the Liberal government. Later, the Coalition Liberal-Conservative government of David Lloyd George used its wartime support to call a "coupon election" in 1918 in which candidates endorsed by the government with a "Coalition Coupon" won a massive landslide and decimated the Liberal Party.[18][22]

World War II edit

- During World War II, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill enjoyed massive popularity in the United Kingdom for opposing the National Government's foreign policy of appeasement towards Nazi Germany before the war and for saving the country from near-defeat in the Battle of Britain afterwards. All major parties in the British Parliament, including the opposition Labour Party, joined Churchill's war ministry. His approval ratings never declined below 78 percent for his entire wartime premiership. Churchill's personal popularity did not extend to the Conservative Party, which opposed the welfare state advocated by Labour and remained associated with appeasement and interwar unemployment and poverty. As a result the Conservatives heavily lost the 1945 general election to Labour.[23][24][25]

Russo-Ukrainian War edit

- The Russo-Ukrainian War caused an increase of support for President Vladimir Putin in Russia. His approval rating rose 10 percent to 71.6 percent after he announced the Russian annexation of Crimea.[26] His approval rating also rose to 69 percent, as did the support for Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin, during the build-up to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[27]

- The war caused an even larger boost of both domestic and international support for Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, with his approval rating rising from 30 percent to 90 percent in Ukraine and also rising to 70 percent in the United States.[28]

In a pandemic edit

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 briefly resulted in popularity spikes for several world leaders. President Donald Trump's approval rating saw a slight increase during the outbreak in early 2020.[29] In addition to Trump, other heads of government in Europe also gained in popularity.[30] French President Emmanuel Macron, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson became "very popular" in the weeks following the pandemic hitting their respective nations.[30] Johnson, in particular, who "became seriously ill himself" from COVID-19, led his government to become "the most popular in decades."[30][31] It was uncertain how long their increase in the approval polls would last, but former NATO secretary general George Robertson opined, "People do rally around, but it evaporates fast."[30]

Controversy and fears of misuse edit

There are fears that the president will misuse the rally 'round the flag effect. These fears come from the "diversionary theory of war" in which the President creates an international crisis in order to distract from domestic affairs and to increase their approval ratings through a rally 'round the flag effect. The fear associated with this theory is that a President can create international crises to avoid dealing with serious domestic issues or to increase their approval rating when it begins to drop.[32]

In popular culture edit

- Wag the Dog is a movie released by coincidence a month just before the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal with high likenesses to the events of the affair. To divert attention on a sex scandal, the American president fabricates a war in a terrorist Albania (one can note that Albania is a majority Muslim—yet not decisively—country). The movie was also remade two years later.

See also edit

- Battle Cry of Freedom, an American Civil War song that urged union supporters to "rally 'round the flag", that was also used for Abraham Lincoln's re-election campaign.

- United States presidential approval rating

- Flag-waving

References edit

- ^ a b Goldstein, Joshua S.; Pevehouse, Jon C. (2008). International Relations: Eighth Edition. New York: Pearson Longman.

- ^ Mueller, John (1970). "Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson". American Political Science Review. 64 (1): 18–34. doi:10.2307/1955610. JSTOR 1955610. S2CID 144178825.

- ^ a b c d e Hetherington, Marc J.; Nelson, Michael (2003). "Anatomy of a Rally Effect: George W. Bush and the War on Terrorism". PS: Political Science and Politics. 36 (1): 37–42. doi:10.1017/S1049096503001665. JSTOR 3649343. S2CID 154505157.

- ^ Baker, William D.; Oneal, John R. (2001). "Patriotism or Opinion Leadership?: The Nature and Origins of the 'Rally 'Round the Flag' Effect". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 45 (5): 661–687. doi:10.1177/0022002701045005006. JSTOR 3176318. S2CID 154579943.

- ^ a b Chapman, Terrence L.; Reiter, Dan (2004). "The United Nations Security Council and the Rally 'Round the Flag Effect". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 48 (6): 886–909. doi:10.1177/0022002704269353. JSTOR 4149799. S2CID 154622646.

- ^ Lian, Bradley; O'Neal, John R. (1993). "Presidents, the Use of Military Force, and Public Opinion". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 37 (2): 277–300. doi:10.1177/0022002793037002003. JSTOR 174524. S2CID 154815976..

- ^ Baum, Matthew A. (2002-06-01). "The Constituent Foundations of the Rally-Round-the-Flag Phenomenon". International Studies Quarterly. 46 (2): 263–298. doi:10.1111/1468-2478.00232. ISSN 1468-2478.

- ^ Kuijpers, Dieuwertje (2019). "Rally around All the Flags: The Effect of Military Casualties on Incumbent Popularity in Ten Countries 1990–2014". Foreign Policy Analysis. 15 (3): 392–412. doi:10.1093/fpa/orz014.

- ^ Myrick, Rachel (2021). "Do External Threats Unite or Divide? Security Crises, Rivalries, and Polarization in American Foreign Policy". International Organization. 75 (4): 921–958. doi:10.1017/S0020818321000175. ISSN 0020-8183.

- ^ Seo, TaeJun; Horiuchi, Yusaku (2023). "Natural Experiments of the Rally 'Round the Flag Effects Using Worldwide Surveys". Journal of Conflict Resolution. doi:10.1177/00220027231171310. ISSN 0022-0027.

- ^ Chávez, Kerry; Wright, James (2022). "International Crisis Termination and Presidential Approval". Foreign Policy Analysis. 18 (3). doi:10.1093/fpa/orac005.

- ^ Smith, Tom W. (2003). "Trends: The Cuban Missile Crisis and U.S. Public Opinion". The Public Opinion Quarterly. 67 (2): 265–293. doi:10.1086/374575. JSTOR 3521635.

- ^ Callaghan, Karen J.; Virtanen, Simo (1993). "Revised Models of the 'Rally Phenomenon': The Case of the Carter Presidency". The Journal of Politics. 55 (3): 756–764. doi:10.2307/2131999. JSTOR 2131999. S2CID 154739682..

- ^ "Bush Job Approval Reflects Record 'Rally' Effect". Gallup.com. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ Curran, Margaret Ann; Schubert, James N.; Stewart, Patrick A. (2002). "A Defining Presidential Moment: 9/11 and the Rally Effect". Political Psychology. 23 (3): 559–583. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00298. JSTOR 3792592.

- ^ "Obama Approval Rallies Six Points to 52% After Bin Laden Death". Gallup.com. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ "The Rise and Fall of the Second International". jacobin.com. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ a b c d Robson, Stuart (2007). The First World War (1 ed.). Harrow, England: Pearson Longman. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4058-2471-2 – via Archive Foundation.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Social Democratic Party | History, Policies, Platform, Leader, & Structure | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ Gilbert, Felix (1984). The End of the European Era, 1890 to the Present (3 ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 126–140. ISBN 0-393-95440-4. OCLC 11091162.

- ^ Gilbert 1984, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Gilbert 1984, pp. 47–57.

- ^ Thorpe, Andrew (2008). A History of the British Labour Party (3 ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 117–119. ISBN 978-0-230-50010-5. OCLC 222250341.

- ^ "How Churchill Led Britain To Victory In The Second World War". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ "Winston Churchill - Leadership during World War II | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ Arutunyan, Anna. "Putin's move on Crimea bolsters popularity back home". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ "Putin's public approval soared as Russia prepared to attack Ukraine. History shows it's unlikely to last". PBS NewsHour. 2022-02-24. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ "Zelensky versus Putin: the Personality Factor in Russia's War on Ukraine | Wilson Center". www.wilsoncenter.org. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ "Trump's Reelection May Hinge On The Economy — And Coronavirus". fivethirtyeight.com. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ a b c d Erlanger, Steven (April 16, 2020). "Popular support Lifts Leaders Everywhere. It May Not Last". The New York Times. p. A6.

- ^ "Patient number one; Missing Boris: The illness of a man who once divided the nation has united it". The Economist. April 11–17, 2020. pp. 34–36.

- ^ Tir, Jaroslav (2010). "Territorial Diversion: Diversionary Theory of War and Territorial Conflict". The Journal of Politics. 72 (2): 413–425. doi:10.1017/s0022381609990879. JSTOR 10.1017/s0022381609990879. S2CID 154480017.