Summary

Robert Nozick (/ˈnoʊzɪk/; November 16, 1938 – January 23, 2002) was an American philosopher. He held the Joseph Pellegrino University Professorship at Harvard University,[3] and was president of the American Philosophical Association. He is best known for his book Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974), a libertarian answer to John Rawls' A Theory of Justice (1971), in which Nozick proposes his minimal state as the only justifiable form of government. His later work, Philosophical Explanations (1981), advanced notable epistemological claims, namely his counterfactual theory of knowledge. It won the Phi Beta Kappa Society's Ralph Waldo Emerson Award the following year.

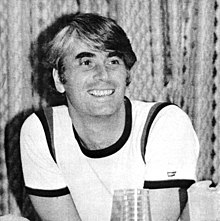

Robert Nozick | |

|---|---|

Nozick in 1977 | |

| Born | November 16, 1938 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | January 23, 2002 (aged 63) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Education | Columbia University (BA) Princeton University (PhD) Oxford University |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic Libertarianism |

| Doctoral advisors | Carl Gustav Hempel |

Main interests | Political philosophy, ethics, epistemology |

Notable ideas | Utility monster, experience machine, entitlement theory of justice, Nozick's Lockean proviso,[1] Wilt Chamberlain argument, paradox of deontology,[2] deductive closure, Nozick's four conditions on knowledge, rejection of the principle of epistemic closure |

Nozick's other work involved ethics, decision theory, philosophy of mind, metaphysics and epistemology. His final work before his death, Invariances (2001), introduced his theory of evolutionary cosmology, by which he argues invariances, and hence objectivity itself, emerged through evolution across possible worlds.[4]

Personal life edit

Nozick was born in Brooklyn to a family of Jewish descent. His mother was born Sophie Cohen, and his father was a Jew from a Russian shtetl who had been born with the name Cohen and who ran a small business.[5]

Nozick attended the public schools in Brooklyn. He was then educated at Columbia College, Columbia University (A.B. 1959, summa cum laude), where he studied with Sidney Morgenbesser; Princeton University (PhD 1963) under Carl Hempel; and at Oxford University as a Fulbright Scholar (1963–1964).

At one point, Nozick joined the Young People's Socialist League, and at Columbia University he founded the local chapter of the Student League for Industrial Democracy. He began to move away from socialist ideals when exposed to Friedrich Hayek's The Constitution of Liberty, claiming he "was pulled into libertarianism reluctantly" when he found himself unable to form satisfactory responses to libertarian arguments.[6]

After receiving his undergraduate degree in 1959, he married Barbara Fierer. They had two children, Emily and David. The Nozicks eventually divorced; Nozick later married the poet Gjertrud Schnackenberg.

Nozick died in 2002 after a prolonged struggle with stomach cancer.[7] He was interred at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Career and works edit

Political philosophy edit

Nozick's first book, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974), argues that only a minimal state limited to the functions of protection against "force, fraud, theft, and administering courts of law" can be justified, as any more extensive state would violate people's individual rights.[8]

Nozick believed that a distribution of goods is just when brought about by free exchange among consenting adults, trading from a baseline position where the principles of entitlement theory are upheld. In one example, Nozick uses the example of basketball player Wilt Chamberlain to show that even when large inequalities subsequently emerge from the processes of free transfer (i.e. paying extra money just to watch Wilt Chamberlain play), the resulting distributions are just so long as all consenting parties have freely consented to such exchanges.

Anarchy, State, and Utopia is often contrasted to John Rawls's A Theory of Justice in popular academic discourse, as it challenged the partial conclusion of Rawls's difference principle, that "social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are to be of greatest benefit to the least-advantaged members of society."

Nozick's philosophy also claims a heritage from John Locke's Second Treatise on Government and seeks to ground itself upon a natural law doctrine, but breaks distinctly with Locke on issues of self-ownership by attempting to secularize its claims. Nozick also appealed to the second formulation of Immanuel Kant's categorical imperative: that people should be treated as an end in themselves, not merely as a means to an end. Nozick terms this the 'separateness of persons', saying that "there are is no social entity...there are only individual people", and that we ought to "respect and take account of the fact that [each individual] is a separate person".[9]

Most controversially, Nozick argued that consistent application of libertarian self-ownership would allow for consensual, non-coercive enslavement contracts between adults. He rejected the notion of inalienable rights advanced by Locke and most contemporary capitalist-oriented libertarian academics, writing in Anarchy, State, and Utopia that the typical notion of a "free system" would allow individuals to voluntarily enter into non-coercive slave contracts.[10][11][12][13]

Anarchy, State, and Utopia received a National Book Award in the category of Philosophy and Religion in the year following its original publication.[14]

Thought experiments regarding utilitarianism edit

Early sections of Anarchy, State, and Utopia, akin to the introduction of A Theory of Justice, see Nozick implicitly join Rawls's attempts to discredit utilitarianism. Nozick's case differs somewhat in that it mainly targets hedonism and relies on a variety of separate intuition pumps, although both works draw from Kantian principles.

Most famously, Nozick introduced the experience machine in an attempt to show that ethical hedonism is not truly what individuals desire, nor what we ought to desire:

There are also substantial puzzles when we ask what matters other than how people's experiences feel "from the inside." Suppose there were an experience machine that would give you any experience you desired. Superduper neuropsychologists could stimulate your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book. All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain. Should you plug into this machine for life, preprogramming your life's experiences?[15]

Nozick claims that life in an experience machine would have no value, and provides several explanations as to why this might be, including (but not limited to): the want to do certain things, and not just have the experience of doing them; the want to actually become a certain sort of person; and that plugging into an experience machine limits us to a man-made reality.

Another intuition pump Nozick proposes is the utility monster, a thought experiment designed to show that average utilitarianism could lead to a situation where the needs of the vast majority were sacrificed for one individual. In his exploration of deontological ethics and animal rights, Nozick coins the phrase "utilitarianism for animals, Kantianism for people", wherein the separateness of individual humans is acknowledged but the only moral metric assigned to animals is that of maximising pleasure:

[Utilitarianism for animals, Kantianism for people] says: (1) maximize the total happiness of all living beings; (2) place stringent side constraints on what one may do to human beings.[16]

Before introducing the utility monster, Nozick raises a hypothetical scenario where someone might, "by some strange causal connection", kill 10,000 unowned cows to die painlessly by snapping their fingers, asking whether it would be morally wrong to do so.[17] On the calculus of pleasure that "utilitarianism for animals, Kantianism for people" uses, assuming the death of these cows could be used to provide pleasure for humans in some way, then the (painless) deaths of the cows would be morally permissible as it has no negative impact upon the utilitarian equation.

Nozick later explicitly raises the example of utility monsters to "embarrass [utilitarian theory]": since humans benefit from the mass sacrifice and consumption of animals, and also possess the ability to kill them painlessly (i.e., without any negative effect on the utilitarian calculation of net pleasure), it is permissible humans to maximise their consumption of meat so long as they derive pleasure from it. Nozick takes issue with this as it makes animals "too subordinate" to humans, counter to his view that animals ought to "count for something"[18]a.

Epistemology edit

In Philosophical Explanations (1981), Nozick provided novel accounts of knowledge, free will, personal identity, the nature of value, and the meaning of life. He also put forward an epistemological system which attempted to deal with both the Gettier problem and those posed by skepticism. This highly influential argument eschewed justification as a necessary requirement for knowledge.[19]: ch. 7

Nozick gives four conditions for S's knowing that P (S=Subject / P=Proposition):

- P is true

- S believes that P

- If it were the case that (not-P), S would not believe that P

- If it were the case that P, S would believe that P

Nozick's third and fourth conditions are counterfactuals. He called this the "tracking theory" of knowledge. Nozick believed the counterfactual conditionals bring out an important aspect of our intuitive grasp of knowledge: For any given fact, the believer's method (M) must reliably track the truth despite varying relevant conditions. In this way, Nozick's theory is similar to reliabilism. Due to certain counterexamples that could otherwise be raised against these counterfactual conditions, Nozick specified that:

- If P weren't the case and S were to use M to arrive at a belief whether or not P, then S wouldn't believe, via M, that P.

- If P were the case and S were to use M to arrive at a belief whether or not P, then S would believe, via M, that P. [20]

A major feature of Nozick's theory of knowledge is his rejection of the principle of deductive closure. This principle states that if S knows X and S knows that X implies Y, then S knows Y. Nozick's truth tracking conditions do not allow for the principle of deductive closure.

Later works edit

The Examined Life (1989), aimed towards a more general audience, explores themes of love, the impact of death, questions of faith, the nature of reality, and the meaning of life. The book takes its name from the quote by Socrates, that "the unexamined life is not worth living". In it, Nozick attempts to find meaning in everyday experiences, and considers how we might come to feel "more real".[21] In this pursuit, Nozick discusses the death of his father, reappraises the experience machine, and proposes "the matrix of reality" as a means of understanding how individuals might better connect with reality in their own lives.[22]

The Nature of Rationality (1993) presents a theory of practical reason that attempts to embellish classical decision theory. In this work, Nozick grapples with Newcomb's problem and the Prisoner's Dilemma, and introduces the concept of symbolic utility to explain how actions might symbolize certain ideas, rather than being carried out to maximize expected utility in the future.

Socratic Puzzles (1997) is a collection of Nozick's previous papers alongside some new essays. While the discussions are quite disparate, the essays generally draw from Nozick's previous interests in both politics and philosophy. Notably, this includes Nozick's 1983 review of The Case for Animal Rights by Tom Regan, where says animal rights activists are often considered "cranks" and appears to go back on the vegetarian position he previously maintained in Anarchy, State and Utopia.[23][24]

Nozick's final work, Invariances (2001), applies insights from physics and biology to questions of objectivity in such areas as the nature of necessity and moral value. Nozick introduces his theory of truth, in which he leans towards a deflationary theory of truth, but argues that objectivity arises through being invariant under various transformations. For example, space-time is a significant objective fact because an interval involving both temporal and spatial separation is invariant, whereas no simpler interval involving only temporal or only spatial separation is invariant under Lorentz transformations. Nozick argues that invariances, and hence objectivity itself, emerged through a theory of evolutionary cosmology across possible worlds.[25]

Later reflections on libertarianism edit

Nozick pronounced some misgivings about libertarianism – specifically his own work, Anarchy, State and Utopia – in his later publications. Some later editions of The Examined Life advertise this fact explicitly in the blurb, saying Nozick "refutes his earlier claims of libertarianism" in one of the book's essays, "The Zigzag of Politics". In the introduction of The Examined Life, Nozick says his earlier works on political philosophy "now [seem] seriously inadequate", and later repeats this claim in the first chapter of The Nature of Rationality.[26][27]

In these works, Nozick also praised political ideals which ran contrary to the arguments canvassed in Anarchy, State and Utopia. In The Examined Life, Nozick proposes wealth redistribution via an inheritance tax and upholds the value of liberal democracy.[28] In The Nature of Rationality, Nozick calls truth a primary good, explicitly appropriating Rawls' A Theory of Justice.[29] In the same work, however, Nozick implies that minimum wage laws are unjustb, and later denigrates Marxism before vindicating capitalism, making reference to Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations.[30]

Nozick also broke away from libertarian principles in his own personal life, invoking rent control laws against Erich Segal – who was at one point Nozick's landlord – and winning over $30,000 in a settlement. Nozick later claimed to regret doing this, saying he was moved by "intense irritation" with Segal and his legal representatives at the time, and was quoted in an interview saying "sometimes you have to do what you have to do."[31]

Some of Nozick's later works seem to endorse libertarian principles. In Invariances, Nozick advances the "four layers of ethics", which at its core maintains an explicitly libertarian underpinning.[32] In Socratic Puzzles, Nozick republished some of his old essays with a libertarian grounding, such as "Coercion" and "On The Randian Argument", alongside new essays such as "On Austrian Methodology" and "Why Do Intellectuals Oppose Capitalism?". However, Nozick does allude to some continued reservations about libertarianism in its introduction, saying that "it is disconcerting to be known primarily for an early work".[33]

Scholars and journalists have since debated what Nozick's true political position was before the end of his life.[34] Writing for Slate, Stephen Metcalf notes one of Nozick's core claims in The Examined Life, that actions done through government serve as markers of "our human solidarity". Metcalf then postulates that Nozick felt this was threatened by neoliberal politics.[35] Libertarian journalist Julian Sanchez, who interviewed Nozick shortly before his death, claims that Nozick "always thought of himself as a libertarian in a broad sense, right up to his final days, even as his views became somewhat less 'hardcore.'"[36]

Philosophical method edit

Nozick was sometimes admired for the exploratory style of his philosophizing, often content to raise tantalizing philosophical possibilities and then leave judgment to the reader. In his review of The Nature of Rationality, Anthony Gottlieb praised this style, noting its place in Nozick's approach to writing philosophy:

"From Mr. Nozick you always expect fireworks, even if some of them go off in their box...Start pondering a sentence and you will find yourself led away prematurely by a parenthetical question; think about the question and you will be dragged into a discursive footnote...Yet it is worth the effort – certainly for regular readers of philosophy, and often for others."[37]

Jason Brennan has related this point to Nozick's "surprising amount of humility, at least in his writings". Brennan makes a point of showing how this enabled Nozick to reach surprising conclusions while also drawing attention to one of Nozick's more famous quotes which also made the headline of his obituary in The Economist, that "there is room for words on subjects other than last words".[38][39]

Nozick was also notable for drawing from literature outside of philosophy, namely economics, physics, evolutionary biology, decision theory, anthropology, and computer science, amongst other disciplines.[40][41]

Popular culture edit

In the 23rd episode of HBO's show The Sopranos, a eyewitness to one of Tony Soprano's crimes is seen at home reading Anarchy, State, and Utopia, by Robert Nozick. Dani Rodrik uses Bo Rothstein's view to point out that the TV show runners take a position in the debate by how they showed the eyewitness reacting to finding out the man they pointed out as the culprit of the crime he saw was actually the local mafia boss, immediately after the book appears on screen.[42]

Bibliography edit

- Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974) ISBN 0-631-19780-X

- Philosophical Explanations (1981) ISBN 0-19-824672-2

- The Examined Life (1989) ISBN 0-671-72501-7

- The Nature of Rationality (1993/1995) ISBN 0-691-02096-5

- Socratic Puzzles (1997) ISBN 0-674-81653-6

- Invariances: The Structure of the Objective World (2001/2003) ISBN 0-674-01245-3

See also edit

- American philosophy

- Classical liberalism

- List of American philosophers

- List of liberal theorists

- A Theory of Justice: The Musical! – in which a fictional Nozick is one of the characters

References edit

- ^ Mack, Eric (May 30, 2019). "Robert Nozick's Political Philosophy". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ "How can a concern for the non-violation of C [i.e. some deontological constraint] lead to refusal to violate C even when this would prevent other more extensive violations of C?": Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia, Basic Books (1974), p. 30 as quoted by Ulrike Heuer, "Paradox of Deontology, Revisited", in: Mark Timmons (ed.), Oxford Studies in Normative Ethics. Oxford University Press (2011).

- ^ "Robert Nozick, 1938–2002". Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, November 2002: 76(2).

- ^ Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, Volume 1, edited by John R. Shook, Thoemmes Press, 2005, p.1838

- ^ "Professor Robert Nozick". Daily Telegraph. 2002. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Albert Zlabinger (December 1, 1977). "An Interview with Robert Nozick". www.libertarianism.org. CATO Institute. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ For biographies, memorials, and obituaries see:

- Feser, Edward (May 4, 2005). "Robert Nozick (1938–2002)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Obituary:Professor Robert Nozick". Daily Telegraph. January 28, 2002. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- Ryan, Alan (April 12, 2014). "Obituary: Professor Robert Nozick". The Independent. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- Schaefer, David Lewis. "Robert Nozick and the Coast of Utopia". The New York Sun. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- O'Grady, Jane (February 1, 2007). "Robert Nozick: Leftwing political philosopher whose rightward shift set the tone for the Reagan-Thatcher era". The Guardian. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

correction from original of 26 January 2002

- Philosopher Nozick dies at 63 From the Harvard Gazette Archived September 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Robert Nozick Memorial minute Archived January 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Feser, Edward. "Robert Nozick (1938—2002)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books. p. 32-33.

- ^ Ellerman, David (September 2005). "Translatio versus Concessio: Retrieving the Debate about Contracts of Alienation with an Application to Today's Employment Contract" (PDF). Politics & Society. 35 (3). Sage Publications: 449–80. doi:10.1177/0032329205278463. S2CID 158624143. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ A summary of the political philosophy of Robert Nozick by R. N. Johnson Archived February 4, 2002, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jonathan Wolff (October 25, 2007). "Robert Nozick, Libertarianism, And Utopia"

- ^ Nozick on Newcomb's Problem and Prisoners' Dilemma by S. L. Hurley Archived March 1, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "National Book Awards – 1975 [https://web.archive.org/web/20110909065656/http://www.nationalbook.org/nba1975.html Archived September 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. National Book Foundation. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books. p. 42-43.

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books. p. 39.

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books. p. 36.

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books. p. 35-42.

- ^ Schmidtz, David (2002). Robert Nozick. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00671-6.

- ^ Keith Derose, Solving the Skeptical Problem

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1989). The Examined Life: Philosophical Meditations, p.7-8, p.15. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-72501-3

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1989). The Examined Life: Philosophical Meditations, p.182-183. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-72501-3

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1989). Socratic Puzzles, p.280-285. Harvard University Press.

- ^ "Animal Rights". The New York Times. December 18, 1983.

- ^ Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, Volume 1, edited by John R. Shook, A&C Black, 2005, p.1838

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1989). The Examined Life: Philosophical Meditations, p.17. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-72501-3

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1989). The Nature of Rationality, p.32. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02096-5

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1989). The Examined Life: Philosophical Meditations, p.28-32. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-72501-3

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1989). The Nature of Rationality, p.68. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02096-5

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1989). The Nature of Rationality, p.27, p.130-131. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02096-5

- ^ Sanchez, Julian (April 8, 2003). "Nozick's Apartment". Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ^ Nozick, Robert (2001). Invariances, p.280-282. Harvard University Press

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1989). Socratic Puzzles, p.17. Harvard University Press.

- ^ Herbjørnsrud, Dag (2002). Leaving Libertarianism: Social Ties in Robert Nozick's New Philosophy. Oslo, Norway: University of Oslo.

- ^ Metcalf, Stephen (June 24, 2011). "The Liberty Scam: Why even Robert Nozick, the philosophical father of libertarianism, gave up on the movement he inspired". slate.com. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Julian Sanchez, "Nozick, Libertarianism, and Thought Experiments".

- ^ Gottlieb, Anthony. "Why Do You Do the Things You Do?". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Brennan, Jason. "Nozick on Philosophical Explorations: There is Room for Words other than Last Words". Bleeding Heart Libertarians. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Not all words need be last words". The Economist. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Williams, Bernard. "Cosmic Philosopher". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Rodrik, Dani (September 5, 2009). "Tony Soprano and Robert Nozick". Dani Rodrik's weblog.

Notes edit

- a.^ Nozick's discussion of animal rights pre-dates Peter Singer's more comprehensive Animal Liberation. Singer's utilitarian position on animal rights was known to Nozick at the time, however, and he expresses misgivings about this in Chapter 3 (footnote 11) of Anarchy, State and Utopia.

- b.^ From p.27 of The Nature of Rationality: "On these grounds, one might claim that certain antidrug enforcement measures symbolize reducing the amount of drug use and that minimum wage laws symbolize helping the poor"

Further reading edit

- Cohen, G. A. (1995). "Robert Nozick and Wilt Chamberlain: How Patterns Preserve Liberty". Self-Ownership, Freedom, and Equality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–37. ISBN 978-0521471749. OCLC 612482692.

- Frankel Paul, Ellen; Fred D. Miller, Jr. and Jeffrey Paul (eds.), (2004) Natural Rights Liberalism from Locke to Nozick, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521615143

- Frankel Paul, Ellen (2008). "Nozick, Robert (1938–2002)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Cato Institute. pp. 360–62. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n220. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Mack, Eric (2014) Robert Nozick's Political Philosophy, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, June 22, 2014.

- Robinson, Dave & Groves, Judy (2003). Introducing Political Philosophy. Icon Books. ISBN 184046450X.

- Schaefer, David Lewis (2008) Robert Nozick and the Coast of Utopia, The New York Sun, April 30, 2008.

- Wolff, Jonathan (1991), Robert Nozick: Property, Justice, and the Minimal State. Polity Press. ISBN 978-0745680453

External links edit

- Robert Nozick at Find a Grave

- Robert Nozick: Political Philosophy – overview of Nozick in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Robert Nozick at Curlie