Summary

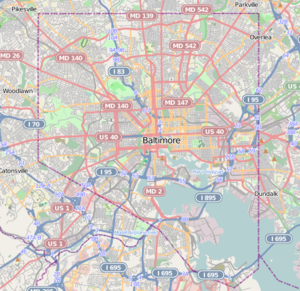

SS John W. Brown is a Liberty ship, one of two still operational and one of three preserved as museum ships.[6] As a Liberty ship, she operated as a merchant ship of the United States Merchant Marine during World War II and later was a vocational high school training ship in New York City for many years. Now preserved, she is a museum ship and cruise ship berthed at Pier 13 in Baltimore Harbor in Maryland.

SS John W. Brown on the Great Lakes in 2000.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | John W. Brown |

| Namesake | John W. Brown |

| Ordered | 1 May 1941 |

| Builder | Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard, Sparrows Point, Maryland |

| Laid down | 28 July 1942 |

| Launched | 7 September 1942 |

| Sponsored by | Annie Green |

| Completed | 19 September 1942 |

| Acquired | 19 September 1942 |

| In service | 19 September 1942 |

| Out of service | 19 November 1946 |

| Identification |

|

| Honors and awards | |

| Fate |

|

| Status | Seagoing museum ship operated by Project Liberty Ship |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type |

|

| Tonnage | |

| Displacement | |

| Length | |

| Beam | 57 feet (17 m) |

| Draft | 27 ft 9.25 in (8.4646 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 11.5 knots (21.3 km/h; 13.2 mph) |

| Range | 23,000 miles (20,000 nmi; 37,000 km) |

| Capacity | 562,608 cubic feet (15,931.3 m3) grain (as cargo ship) |

| Troops | Up to 450,[2] 550,[3] or 650[4] (sources) as "Limited Capacity Troopship" |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Notes | As of September 2007, the bow 3-inch gun and several 20-mm cannon were rigged with compressed gas firing simulators (oxygen and a fuel gas) for historical re-enactments of air defense |

SS John W. Brown (Liberty Ship) | |

| |

| Location | Canton Pier 13, 4601 Newgate Avenue, Baltimore, Maryland |

| Coordinates | 39°15′35″N 76°33′22″W / 39.25972°N 76.55611°W |

| Built | 1942 |

| Architect | Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard, Baltimore, Maryland |

| NRHP reference No. | 97001295[5] |

| Added to NRHP | 17 November 1997 |

John W. Brown was named after the Canadian-born American labor union leader John W. Brown (1867–1941).[7]

The other surviving operational Liberty ship is SS Jeremiah O'Brien in San Francisco, California. A third Liberty ship, SS Hellas Liberty (ex-SS Arthur M. Huddell) is preserved as a static museum ship in Piraeus, Greece.

Construction edit

The United States Maritime Commission ordered John W. Brown as an ECS-S-C1 Maritime Commission Emergency Cargo Ship, the type of ship that would become popularly known as the "Liberty ship", hull number 312 on 1 May 1941.[8] She was laid down at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard in Baltimore, Maryland, on 28 July 1942 and – sponsored by Annie Green, the wife of the president of the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers – was launched on 7 September 1942, the third of three Liberty ships launched at the yard that day. She completed fitting out on 19 September 1942, making her total construction time only 54 days. She required about 500,000 man-hours and cost $1,750,000 to build and was the 62nd of the 384 Liberty ships constructed at the Bethlehem-Fairfield yard.[2][9]

The Worthington Pump & Machine Corporation of Harrison, New Jersey, built John W. Brown's vertical triple expansion steam engine, which cost $100,000.[4]

Service history edit

World War II edit

Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard delivered John W. Brown to her owner, the Maritime Commission, on the day of her completion. With States Marine Corporation as her general agent, John W. Brown was operated initially by the War Shipping Administration and later by the United States Army's Army Transport Service.[10][11]

After ten more days of post-delivery work in Baltimore to prepare her to get underway, John W. Brown departed on 29 September 1942 to steam down the Chesapeake Bay to Norfolk, Virginia, where she underwent degaussing and deperming to make her less likely to trigger magnetic sea mines. Departing Norfolk, she proceeded back north through the Chesapeake Bay, anchored off Annapolis, Maryland, overnight on 3–4 October 1942, and then passed through the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal and Delaware River to Delaware Bay, where she joined a convoy of four merchant ships. Escorted by three escort vessels and a United States Navy blimp, the convoy proceeded up the coast of New Jersey to New York City, where on 6 October 1942 John W. Brown began loading her first cargo – 8,381 long tons (9,387 short tons; 8,515 metric tons) of cargo destined for the Soviet Union, consisting of two Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters, 10 M4 Sherman tanks, 200 motorcycles, 100 jeeps, over 700 long tons (784 short tons, 711 metric tons) of ammunition, and over 250 long tons (280 short tons, 254 metric tons) of canned pork lunch meat – at Pier 17 in Brooklyn. While in New York, she also had the Oerlikon 20 mm cannon mounted on her bow replaced by a 3-inch (76 mm)/50-caliber gun, and she interrupted her loading of cargo on 9 October 1942 for work on the degaussing and compass adjusting ranges.[12]

Maiden voyage, October 1942–March 1943 edit

With loading complete on 14 October 1942, John W. Brown departed New York on 15 October on her maiden voyage, bound for the Persian Gulf, where she would unload her cargo for delivery overland to the Soviet Union. Her 14,400-nautical mile (16,560-statute mile; 26,667-km) route was designed to allow her to avoid the areas where Axis forces posed the greatest threats to shipping. She made the first leg of the voyage in convoy, steaming down the United States East Coast to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where she joined another convoy for the trip across the Caribbean Sea to the Panama Canal. After passing through the canal and reaching the Pacific Ocean, she steamed alone down the west coast of South America, requiring two weeks to reach Cape Horn. She then made a 17-day independent crossing of the South Atlantic Ocean to Cape Town, South Africa, where she stopped for two days to refuel and reprovision. Getting back underway, she steamed alone north through the western Indian Ocean off the east coast of Africa, and anchored in the Persian Gulf on 25 December 1942, two and a half months after leaving New York.[10][11][13]

Ports in the Persian Gulf were overwhelmed by the amount of cargo arriving from Allied countries, and so John W. Brown was forced to lie at anchor for a month until she could begin to unload at Abadan, Iran, where she dropped off the two P-40s and some of the tanks in late January 1943. It took another month and a half until she could enter port at Khorramshahr, Iran, and unload the rest of her cargo in March 1943.[14]

On 16 March 1943, John W. Brown got underway to return to the United States. She steamed south from the Persian Gulf along the east coast of Africa to Cape Town, again calling there for two days before making a two-week crossing of the South Atlantic to Bahia, Brazil, where she arrived on 23 April 1943. There she joined a convoy to steam north to Paramaribo in Surinam, proceeded upriver to Paranam to load bauxite, then steamed to Port of Spain, Trinidad, to load more bauxite. Fully loaded, she joined a convoy to steam to Guantanamo Bay and then another convoy for the final leg of her voyage to New York City, where she arrived on 27 May 1943 to complete a maiden voyage of about eight months.[10][11][14]

Conversion to troopship edit

John W. Brown's maiden voyage was her only one as a standard cargo ship.[3] After returning to the United States, she became the first of 220 Liberty ships to undergo conversion into a "Limited Capacity Troopship" capable of transporting up to 450,[2] 550,[3] or 650[4] (sources vary) troops or prisoners-of-war. Her modifications – which took place at Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation's Hoboken Shipyard in Hoboken, New Jersey – included the installation of bunks stacked five deep for the embarked passengers on her forward tweendeck, additional shower and head facilities for them, two additional diesel-powered generators,[3] and the installation of two more Oerlikon 20-mm automatic cannons.[2][3][14][15]

Second voyage June–August 1943 edit

After completion of her conversion at Hoboken, John W. Brown returned to New York to load for her second voyage, her first as a troopship. Her 5,023 long tons (5,626 short tons; 5,103 metric tons) of cargo consisted mostly of food, and her passenger list included 306 men – seven United States Army officers, 145 U.S. Army military policemen, three enlisted medical assistants, three Royal Navy officers, and 148 Royal Navy sailors; the Royal Navy personnel were all survivors of a torpedoed ship. She departed New York on 24 June 1943, steamed in convoy to Hampton Roads, Virginia, to meet another part of the convoy, and then set out in convoy for a transatlantic crossing. The convoy transited the Strait of Gibraltar and entered the Mediterranean Sea on 18 July 1943, and John W. Brown arrived at Algiers in French Algeria on 20 July 1943. There she unloaded her cargo and disembarked all of her passengers except for 38 U.S. Army personnel who remained aboard to guard 500 German prisoners-of-war – veterans of the Afrika Korps – that she took aboard to transport to the United States. She departed Algiers on 5 August 1943 and returned in convoy to Hampton Roads, where the convoy arrived safely on 26 August 1943 after a passage in which there were many submarine alerts but no enemy attacks. The German prisoners had all disembarked by the following day.[16]

Third voyage, September 1943–March 1944 edit

For her third voyage, John W. Brown loaded a cargo of 7,845.5 measurement tons (314,180 cubic feet; 8,889 cubic meters) of TNT, gasoline, and general cargo and took aboard 339 U.S. Army personnel – 36 officers and 303 enlisted men – as passengers. Departing Hampton Roads in convoy on 15 September 1943, she arrived at Oran in French Algeria on 4 October 1943 after an uneventful trip. Her passengers disembarked there on 6 October, and she completed unloading her cargo on 15 October. She embarked 15 officers and 346 men of the U.S. Army's 1st Armored Division and loaded 274 of the division's vehicles, including 61 tanks.[16]

On 1 November 1943, John W. Brown departed Oran in convoy on the first of eight Mediterranean shuttle trips she would make during the voyage. After a stop at Augusta, Sicily, her convoy arrived safely at Naples, Italy, on 7 November. She completed unloading there on 11 November, and departed empty on 12 November, proceeding in convoy to Augusta, where she stopped for four days, and then on to Oran, where her convoy arrived on 22 November 1943. After taking aboard 241 American and Free French troops, 261 tank destroyers, trucks, and cars, and a load of asphalt there, she departed in convoy on 30 November and arrived at Naples on 7 December 1943.[17]

Unloaded by 9 December, John W. Brown again left Naples empty on 10 December 1943 in a convoy which stopped for three days at Augusta and then proceeded to Bizerte, Tunisia, where it arrived on 16 December 1943. There she embarked six Free French officers and 305 Free French enlisted men, and loaded 958 tons of trucks, trailers, weapon carriers, ambulances, and cars. She then proceeded in convoy to Pozzuoli Bay, Italy, arriving there on 26 December 1943. On 27 December, the Liberty ship SS Zebulon Pike rode over John W. Brown's anchor cable and collided with her starboard side, causing significant damage. Despite the damage, she continued her voyage, unloading her cargo at Naples and departing empty on 4 January 1944, joining a convoy to Oran which arrived on 10 January. On 13 January, she moved to Mostaganem, French Algeria, where she loaded 5,000 tons of gasoline; she then transported the gasoline to Oran. Unloading it, she took aboard 263 passengers, 186 vehicles, and 799 tons of engineering equipment and supplies; she departed Oran on 29 January, stopped at Augusta, and arrived at Naples on 5 February to discharge her passengers and cargo.[18]

John W. Brown embarked 106 U.S. Army and 13 U.S. Navy personnel and steamed out of Naples on 10 January 1944 in a convoy which stopped at Augusta – where she took a Royal Navy lieutenant aboard – and proceeded to Bizerte, arriving on 14 February 1944. There she dropped off her passengers and loaded a cargo of scrap metal and the personal effects of deceased soldiers.[18]

On 21 February 1944, John W. Brown departed Bizerte in convoy to return to the United States. The following day, the German submarine U-969 attacked the convoy, and the Liberty ships SS Peter Skene Ogden, only 500 yards (457 m) ahead of her, and SS George Cleeve, only 850 yards (777 m) off her starboard bow, suffered torpedo hits causing such severe damage that both ships had to beach themselves and became total losses, but John W. Brown was left unharmed. Her convoy faced several more submarine alerts, but no further enemy attacks occurred, and enemy contacts ceased entirely after the convoy passed through the Strait of Gibraltar into the Atlantic on 25 February 1944. The transatlantic crossing was uneventful except for rough weather, and John W. Brown arrived at New York on 17 March 1944 to complete her third voyage.[18]

On 23 March 1944, John W. Brown steamed up the Hudson River to Yonkers, New York, where she entered Blair Shipyard for repairs to the damage suffered during the collision with Zebulon Pike and to have two more 3-inch 50-caliber guns and quarters for additional United States Navy Armed Guard personnel to man them. The installation of the guns brought her up to her ultimate armament.[19]

Fourth voyage, April–September 1944 edit

Her repairs and alterations complete, John W. Brown steamed to Brooklyn, where on 3 April 1944 she began to load a cargo of high explosives. She departed New York on 10 April to begin her fourth voyage in a convoy to Hampton Roads, where additional ships joined her convoy for a transatlantic passage. The convoy departed Hampton Roads on 13 April 1944 and, despite several alerts, crossed peacefully, transited the Strait of Gibraltar on 29 April 1944, and divided during a 5 May stop at Augusta, where John W. Brown and her section of the convoy left the other ships to steam to Naples, arriving there on 8 May. Discharging her cargo there, John W. Brown embarked five U.S. Army officers and 170 U.S. Army enlisted men and loaded a cargo of 3,322 tons of high explosives and gasoline. She left Naples on 18 April, arriving off the Anzio beachhead the following day, and was present there when the Allies finally broke out of the beachhead on 23 April after a lengthy campaign.[19] She got underway on 24 April and arrived in Naples on 25 April.[19]

On 26 April, John W. Brown embarked 336 German prisoners-of-war and one U.S. Army officer and 38 U.S. Army enlisted men to guard them. With a stop in Augusta, she transported them in convoy to Bizerte, where she arrived on 31 May 1944, disembarked them, and loaded 406 U.S. Army personnel and 939 tons of cargo. Departing on 10 June 1944, she steamed in convoy to Naples, arriving on 14 June to load C rations, life preservers, and life rafts. She then left Naples on 24 June and proceeded in convoy to the Anzio beachhead and discharged her passengers and cargo. On 26 June, she embarked about 1,000 French colonial troops and transported them to Naples, arriving there on 27 June. She departed on 29 June in a convoy to Cagliari, Sardinia, where she embarked 1,017 Italian Co-Belligerent Army troops fighting on the Allied side; she then joined a convoy to Naples, arriving there on 3 July 1944 and disembarking the Italians on 4 July. Next, she repeated the trip, leaving Naples in convoy on 5 July for Cagliari, where she loaded a cargo of ammunition and embarked 144 Royal Air Force personnel and 759 Italian Co-Belligerent Army troops for transportation in convoy to Naples, arriving there on 9 July 1944.[19]

John W. Brown spent the next five weeks at anchor at Naples during preparations for Operation Dragoon, the Allied invasion of southern France. While there, she was dressed overall for the 24 July 1944 tour of the harbor by King George VI of the United Kingdom. Although fully loaded with cargo, 15 U.S. Army officers, and 299 U.S. Army enlisted men by 29 July 1944, she remained at anchor until 13 August, when she finally got underway for the invasion,[19] passing as she left Naples a British destroyer from which British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was flashing his "V for Victory" sign at the passing ships. Her convoy steamed west across the Tyrrhenian Sea, passed through the Strait of Bonifacio into the western Mediterranean Sea, and then proceeded north off the west coast of Corsica and finally northwest to the south coast of France. John W. Brown arrived off the beachhead at Bougnon Bay at 18:00 on 15 August 1944, ten hours after the initial landings, and began unloading her troops and their equipment on 16 August, completing the process on 21 August. During her stay off the beachhead, there were numerous German air attacks and alerts in her vicinity, peaking at six alerts on 17 August; her U.S. Navy Armed Guard gunners may have shot down one German plane during Operation Dragoon, but its destruction was never confirmed.[2][10][11][20][21]

Unloading completed, John W. Brown left the beachhead on 21 August and returned in convoy to Naples, where she arrived on 23 August. She embarked 500 German prisoners-of-war and 33 U.S. Army personnel to guard them on 3 September 1944, departed Naples in convoy the next day, stopped at Augusta, and then left in convoy for the United States. Her convoy had a quiet passage except for heavy weather which worsened as she approached the U.S. East Coast. She arrived at Hampton Roads on 28 September, disembarked the prisoners-of-war at Newport News, Virginia, on 29 September, and then steamed north up the Chesapeake Bay to Baltimore, where she arrived on 30 September 1944 to conclude her fourth voyage.[21]

Fifth voyage, October–December 1944 edit

John W. Brown got underway from Baltimore on 19 October 1944 for her fifth voyage and proceeded to Hampton Roads, where she joined a convoy for a transatlantic passage. Carrying 356 passengers – including 30 United States Army Air Forces fighter pilots and troops of the all-African American 758th Tank Battalion – she departed Hampton Roads in convoy on 22 October 1944. The convoy encountered very bad weather during its trip but did not come under enemy attack, and John W. Brown arrived at Augusta safely on 14 November 1944. She continued on to Naples in convoy on 16 November, arriving the following day. After disembarking the fighter pilots there, she departed on 23 November and moved on to Leghorn, where she discharged her cargo and the rest of her passengers. She loaded mail, steamed to Naples in convoy from 4 to 6 December, loaded cargo, and then departed for Oran, for the first time in her career steaming alone in Mediterranean waters – even burning her running lights at night – thanks to the control the Allies had achieved there by December 1944. Arriving at Oran on 11 December, she unloaded her cargo, and then departed in convoy on 13 December 1944 bound for the United States. Braving high winds and enormous waves but encountering no enemy forces, her convoy arrived safely at New York on 29 December 1944.[22]

Sixth voyage, January–March 1945 edit

On 9 January 1945, John W. Brown, steaming independently, departed New York on her sixth voyage, carrying U.S. Army general cargo and, after a brief stop at Hampton Roads, arrived at Charleston, South Carolina, on 12 January. She loaded more cargo, left Charleston on 17 January, and proceeded independently back to Hampton Roads, arriving there on 19 January. She embarked 54 U.S. Army passengers at Newport News and departed on 23 January in convoy for Naples, at first facing heavy weather but otherwise making an uneventful transatlantic crossing. After passing through the Strait of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean Sea, she left the convoy on 7 February to steam independently to Naples; her engineers shut down her port boiler when it began to malfunction on 9 February, forcing her to continue at reduced speed, but she arrived safely at Naples on 11 February 1945. She disembarked her passengers and repaired her boiler, then left for Leghorn, where she arrived on 19 February.[22] After unloading her cargo, she departed on 27 February, stopped at Piambino, and arrived at Naples on 1 March 1945. She steamed to Oran independently between 2 and 5 March with her running lights burning at night. On 8 March she departed Oran bound for New York in convoy. During the crossing, her port boiler began to malfunction again on 14 February. With her speed reduced, she dropped out of the convoy and proceeded independently as a straggler, but after the boiler was repaired on 16 February she returned to full speed; forgoing the prescribed zigzag steaming pattern for stragglers, she managed to overtake and rejoin her convoy, and arrived with it at New York on 24 March 1945.[23]

John W. Brown was taken under repair by Atlantic Basin Iron Works in Brooklyn from 7 to 11 April to have her balky boiler fixed and have a gyrocompass installed.[23]

Seventh voyage, April–June 1945 edit

On 23 April 1945, John W. Brown left in convoy with a load of U.S. Army general cargo below and trucks lashed to her decks to begin her seventh voyage. The convoy encountered bad weather but no enemy forces while crossing the North Atlantic and arrived off The Downs on the southeast coast of England on V-E Day, 8 May 1945. She then proceeded to Antwerp, Belgium, where she discharged her cargo. Departing on 19 May, she arrived at Le Havre, France, on 22 May. There she embarked 31 U.S. Army officers and 321 U.S. Army enlisted men, some of them liberated prisoners-of-war, and departed on 24 May. She paused in The Solent for two days, then got back underway on 27 May in convoy for the United States, the convoy burning its running lights at night for the first time since the beginning of the war. The convoy arrived at New York on 11 June 1945.[23]

John W. Brown disembarked some of her U.S. Navy Armed Guard personnel at New York and left on 20 June 1945 bound for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where all but four of her remaining Armed Guard personnel left the ship.[23]

Eighth voyage, June–August 1945 edit

On 3 July 1945, John W. Brown left Philadelphia on her eighth voyage. She discharged her cargo at Antwerp, took aboard 419 U.S. Army troops, and departed on 28 July. She arrived at New York to discharge her passengers on 11 August 1945.[23]

On 15 August 1945 (14 August in the United States), V-J Day brought World War II to an end.

Post-war edit

From 17 August to 10 September 1945, John W. Brown underwent alterations at the J. K. Welding Company in Yonkers which increased her troop-carrying capacity to 562. On 13 September 1945, all of her guns were removed, and her last four Navy Armed Guard personnel were detached.[24]

Ninth voyage, September–November 1945 edit

John W. Brown began her ninth voyage on 15 September 1945, departing New York. Arriving in Baltimore the next day, she departed on 25 September 1945 with a cargo of grain. She arrived at Marseilles, France, on 15 October, where she unloaded the grain and embarked 645 U.S. Army personnel, 83 more than her official capacity. She then returned to New York, arriving on 14 November 1945. She soon had radar installed at the Bethlehem Brooklyn 56th Street shipyard in Brooklyn.[24]

Tenth voyage, November 1945–January 1946 edit

The ship's tenth voyage began on November 20, 1945. John W. Brown proceeded up the Hudson River to Albany, New York, where she loaded a cargo of wheat before returning to New York City. On 1 December 1945, she departed New York City and steamed to Naples, arriving there on 20 December 1945. She departed Naples on 3 January 1946 and proceeded to Marseilles, where she arrived on 6 January and embarked 564 men of the U.S. Army's 100th Infantry Division. On 7 January she got underway for New York, arriving there on 26 January 1946 to discharge the troops. It was her last voyage as a troopship.[24] During her career, John W. Brown had carried nearly 10,000 troops, including the two shiploads of German prisoners-of-war that she transported from North Africa to the United States.[2]

Eleventh voyage, February–April 1946 edit

John W. Brown got underway from New York to begin her eleventh voyage on 16 February 1946. She transited the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal and steamed down the Chesapeake Bay to Baltimore, where she took on a cargo of coal at the Curtis Bay Coal Pier. Leaving on 20 February, she steamed to Copenhagen, Denmark, where she arrived on 11 March 1946. After unloading the coal, she embarked ten civilian airline pilots – nine men and one woman – under United States Government contract to fly planes to Denmark. Departing Copenhagen on 21 March, she returned to Baltimore, arriving there on 6 April 1946. She lay idle for the next two and a half months.[24]

Twelfth voyage, June–July 1946 edit

Finally getting underway again, John W. Brown departed Baltimore on 18 June 1946 to begin her twelfth voyage. Carrying a general cargo, she steamed to Hamburg, Germany, where she arrived on 4 or 5 July. After unloading, she departed Hamburg on 9 July and steamed to New York, arriving there on 23 July 1946.[24]

Thirteenth voyage, August–November 1946 edit

John W. Brown departed New York on 9 August 1946 to begin her thirteenth and final voyage. She steamed to Galveston, Texas, and then on to Houston, Texas, where she loaded a cargo of grain. She then steamed from Houston to Kingston-upon-Hull, United Kingdom, where she arrived on 22 October 1946. After unloading her cargo there, she proceeded to London, where she arrived on 29 October and took a small cargo aboard. Departing London on 1 November 1946, she steamed to New York, arriving there on 15 November 1946. After she unloaded her cargo, John W. Brown's final voyage officially was completed on 19 November 1946, bringing her seagoing career to an end.[25][26]

Training ship edit

New York City's Metropolitan Vocational High School had been without a ship for the training of boys interested in seafaring careers since its school ship, the New York City ferryboat Brooklyn, had been returned to the city at the end of World War II. In August 1946, the Maritime Commission and the City of New York signed a letter of agreement under which the Maritime Commission would loan John W. Brown – whose tweendeck modifications to carry troops gave her a large amount of internal space suitable for classroom use – to the city for educational purposes at no charge, with the city responsible for all expenses related to maintaining the ship and operating her as a static training ship. After John W. Brown completed her final voyage in November 1946, she was towed to her new berth at Manhattan's Pier 4 on the East River on 13 December 1946 to enter service as SS John W. Brown High School, the only floating nautical high school in the United States. The ship served in that capacity as a static training facility from 1946 to 1982, graduating thousands of students prepared to begin careers at sea in the merchant marine, the United States Navy, and the United States Coast Guard. By 1950, she had moved to a new berth at Manhattan's Pier 43 on the East River at the foot of East 25th Street.[3][20][26][27][28]

Training aboard John W. Brown began in December 1946, many of the early students being men who had dropped out of classes at the Metropolitan Vocational High School during World War II to serve as merchant mariners or in the U.S. Navy or U.S. Coast Guard. Students studied standard academic subjects and took boat building, marine radio, marine electrician, and maritime business classes in the high school's main building ashore; aboard John W. Brown they learned their seafaring trade, either as deck hands, engine room personnel, or stewards, and they also performed all maintenance and repairs the ship required. Students at first spent a week at a time in the building and a week at a time on the ship; later, the schedule changed so that they spent half of each school day in the building and the other half aboard the ship. The Maritime Educational Advisory Commission also met regularly aboard the ship and worked closely with the school's staff.[28]

Graduates enjoyed an excellent reputation in the maritime industry.[28] Between 1951 and 1955, 80 percent of the school's graduates gained employment in the maritime industry or in seagoing agencies and forces of the United States Government, a record rivaling that of the United States Merchant Marine Academy, while 40 percent of those who did not complete the course of study and left school at age 17 also secured such jobs. The U.S. Coast Guard also granted additional credit to the school's graduates toward earning a Lifeboat Certificate.[28]

By late 1956, the decline of the American merchant marine, budget problems in New York City, the expense of maintaining, repairing, and operating John W. Brown, and the cost of busing students between the school's main building and the ship had created financial difficulties for the high school that it would never fully overcome. New York City officials gave thought to ending the maritime vocational training program and closing the school, but cost-cutting measures were instituted, such as returning in September 1957 to the schedule of having students study in the school's building for a week at time and aboard ship for a week at time, eliminating the expense of busing.[28] However, continuing budget problems finally led to the school closing in mid-1982, and John W. Brown remained idle in New York Harbor for the next year.[2]

Restoration and heritage edit

When John W. Brown's school-ship days ended, the first Project Liberty Ship was formed in New York City to preserve her. It did not succeed in finding her a berth in New York, and instead she was towed to the James River Reserve Fleet near Norfolk, Virginia,[2] in July 1983 with her future in doubt.

In August 1988, Project Liberty Ship found John W. Brown a berth in Baltimore, Maryland, near where she was built and had her towed there.[2] In September 1988, she was dedicated as a memorial museum at ceremonies at Dundalk Marine Terminal in Dundalk, Maryland.

After three years of restoration effort, on 24 August 1991 John W. Brown steamed under her own power for the first time in nearly 45 years, and completed sea trials in the same waters in the Chesapeake Bay where she had completed her original sea trials in 1942.[29] Four weeks later, on 21 September 1991, two days after the 49th anniversary of her completion, John W. Brown carried about 600 members and guests on her "matron voyage," her inaugural cruise.

In 1994, John W. Brown received U.S. Coast Guard certification for coastwise ocean voyages. In April 1994, she made her first offshore voyage since 1946, steaming to New York Harbor, and in August 1994 she made her first foreign voyage as a museum ship, steaming to Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, then stopping at Boston, Massachusetts, and Greenport, New York, on her way back to Baltimore.

John W. Brown was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on 17 November 1997.[5] In 2000, she visited the Great Lakes for drydocking and hull work in Toledo, Ohio.

In addition to her floating museum role, John W. Brown still gets underway several times a year for six-hour "Living History Cruises" that take the ship through Baltimore Harbor, down the Patapsco River, and into the Chesapeake Bay. Each cruise includes tours of the ship, discussions of the role of the U.S. merchant marine, Liberty ships, and American women in World War II, reenactments of the activities of the ship's World War II U.S. Navy Armed Guard, flybys and simulated attacks on the ship by World War II aircraft, and entertainment by a barbershop quartet and singers, comedians, and actors imitating such World War II figures as President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Andrews Sisters, and Abbott and Costello.[30] As of the end of the 2013 cruising season, she had completed her 97th Living History Cruise and had visited 29 ports along the United States East Coast and the Atlantic coast of Canada and in the Great Lakes.[31] She is the largest cruise ship operating under the American flag on the United States East Coast.[32]

edit

| Voyage | Master[33] | Merchant crew[33] | Officer-in-Charge, U.S. Navy Armed Guard[33] |

U.S. Navy Armed Guard men aboard[33] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Matthew R. Coward |

43 |

Lieutenant, junior grade, Charles F. Calvert |

20

|

2 |

William E. Carley |

47 |

Lieutenant, junior grade, Arley T. Zinn |

28

|

3 |

William E. Carley |

? |

Lieutenant, junior grade, Arley T. Zinn |

?

|

4 |

George M. Brown |

43 |

Ensign Joseph B. Humphreys |

35

|

5 |

George M. Brown |

? |

Lieutenant, junior grade, James P. Argo |

?

|

6 |

George M. Brown |

? |

Lieutenant, junior grade, James P. Argo |

?

|

7 |

Andrew Lihz |

? |

Lieutenant, junior grade, James P. Argo |

14

|

8 |

Andrew Lihz |

? |

Lieutenant, junior grade, Edward H. O'Connor Jr. |

4

|

9 |

Andrew Lihz |

? |

none |

0

|

10 |

Alfred W. Hudnall |

? |

none |

0

|

11 |

Alfred W. Hudnall |

? |

none |

0

|

12 |

Alfred W. Hudnall |

? |

none |

0

|

13 |

Alfred W. Hudnall |

? |

none |

0

|

Honors and awards edit

For her World War II service, John W. Brown was awarded[34] the:

- Merchant Marine Combat Bar

- Merchant Marine Atlantic War Zone Medal

- Merchant Marine Mediterranean-Middle East War Zone Medal

- Merchant Marine Pacific War Zone Medal

- Merchant Marine World War II Victory Medal

As a museum ship, John W. Brown has received the World Ship Trust's Maritime Heritage Award.[34]

See also edit

Citations edit

- ^ Davies, James (May 2004). "Specifications (As-Built)" (PDF). p. 23. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Live, 2013 edition, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f "S.S. John W. Brown Walk-around". geoghegan.us.

- ^ a b c Live, 2013 edition, p. 4.

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 15 April 2008.

- ^ Sawyer (1985) pp. 1–19, 40–41, 223

- ^ Cooper, Sherod, SS John W. Brown: Baltimore's Living Liberty, Project Liberty Ship, 1991, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Live, publication of Project Liberty Ship, 2013 edition, pp. 4, 8.

- ^ Cooper, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d "SS John W. Brown B4611 – Cargo Ship". militaryfactory.com. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Project Liberty Ship: SS John W. Brown Archived 2013-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cooper, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Cooper, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c Cooper, p. 5.

- ^ Project Liberty Ship: Armament Aboard SS John W. Brown Archived 2013-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Cooper, p. 6.

- ^ Cooper, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c Cooper, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e Cooper, p. 8.

- ^ a b Sawyer (1985) pp. 40–41

- ^ a b Cooper, p. 10

- ^ a b Cooper, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e Cooper, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Cooper, p. 13.

- ^ Cooper. p. 14.

- ^ a b John W. Brown Alumni Association: History: Schoolship John W. Brown Part 1: 1874–1946.

- ^ Classmates: SS John W. Brown High School, New York, NY

- ^ a b c d e John W. Brown Alumni Association: History: Schoolship John W. Brown Part 2: 1946–1957

- ^ Live, 2013 edition, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Live, 2013 edition, pp. 18–22.

- ^ Live, 2013 edition, p. 7.

- ^ Remarks of ship's captain, Baltimore Harbor, October 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c d All information in table from Cooper, pp. 3, 6, 8, 10–14

- ^ a b "Historic Naval Ships Association". Archived from the original on 14 October 2007.

References edit

- Sawyer, L. A.; Mitchell, W. H. (1985). The Liberty Ships (second ed.). London: LLoyd's of London Press Ltd.

External links edit

- "Project Liberty Ship". Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2004.

- "SS John W. Brown Alumni Association".

- "Historic Naval Ships Association: SS John W. Brown". Archived from the original on 14 October 2007.

- Photo of SS John W. Brown as a static school ship in New York City in 1965

- Liberty Ship Walk-Around S.S. John W. Brown, with numerous photos

- SS John W. Brown, Baltimore City, including photo from 1986, at Maryland Historical Trust