Summary

SS Mendi was a British 4,230 GRT passenger steamship that was built in 1905 and, as a troopship, sank after collision with great loss of life in 1917.

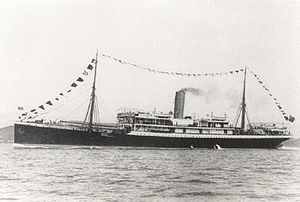

Mendi dressed overall

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Mendi |

| Namesake | Mendi people of West Africa |

| Owner | British and African Steam Navigation Company Ltd, Liverpool |

| Operator | Elder Dempster & Co, Liverpool |

| Builder | Alexander Stephen and Sons |

| Yard number | 404 |

| Launched | 19 June 1905 |

| Fate | Requisitioned 1916 |

| Reclassified | Troopship |

| Fate | Sank after collision on 21 February 1917 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage | 4,230 GRT, 2,639 NRT |

| Length | 370.2 ft (112.8 m) |

| Beam | 46.2 ft (14.1 m) |

| Depth of hold | 23.3 ft (7.1 m) |

| Propulsion | triple expansion steam engine |

| Speed | 11.5 knots (21.3 km/h; 13.2 mph) |

Alexander Stephen and Sons of Linthouse in Glasgow, Scotland launched her on 18 June 1905 for the British and African Steam Navigation Company, which appointed group company Elder Dempster & Co to manage her on their Liverpool-West Africa trades.[1][2] In 1916 during the First World War the UK Admiralty chartered her as a troopship. On 21 February 1917 a large cargo steamship, Darro, collided with her in the English Channel south of the Isle of Wight.[2] Mendi sank, killing 646 people, mostly black South African troops, as well as white Southern African officers and NCOs, and crew.[3][4] The new port admin building at the Port of Ngqura, South Africa, has been named eMendi in commemoration of the SS Mendi.

Final voyage edit

Mendi had sailed from Cape Town carrying 823 men of the 5th Battalion the South African Native Labour Corps to serve in France. She called at Lagos in Nigeria, where a naval gun was mounted on her stern. She next called at Plymouth and then headed up the English Channel toward Le Havre in northern France, escorted by the Acorn-class destroyer HMS Brisk.

Mendi's complement was a mixture characteristic of many UK merchant ships at the time. Officers, stewards, cooks, signallers and gunners were British; firemen and other crew were West Africans, most of them from Sierra Leone.[5]

The South African Native Labour Corps men aboard her came from a range of social backgrounds, and from a number of different peoples spread over the South African provinces and neighbouring territories.[6] (287 were from Transvaal, 139 from the Eastern Cape, 87 from Natal, 27 from Northern Cape, 26 from the Orange Free State, 26 from Basutoland, eight from Bechuanaland (Botswana), five from Western Cape, one from Rhodesia and one from South West Africa). Most had never seen the sea before this voyage, and very few could swim. The officers and NCOs were white Southern Africans.

Loss edit

At 5 am on 21 February 1917, in thick fog about 10 nautical miles (19 km) south of St. Catherine's Point on the Isle of Wight, the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company cargo ship Darro accidentally rammed Mendi's starboard quarter, breaching her forward hold. Darro was an 11,484 GRT ship, almost three times the size of the Mendi, sailing in ballast to Argentina to load meat. Darro survived the collision but Mendi sank, killing 616 Southern Africans, 607 of whom were black troops and nine of whom were white officers & NCOs, and 30 crew.[3][4][7]

Some men were killed outright in the collision; others were trapped below decks. Many others gathered on Mendi's deck as she listed and sank. Oral history records that the men met their fate with great dignity. An interpreter, Isaac Williams Wauchope (also known as Isaac Wauchope Dyobha),[8][9] who had previously served as a Minister in the Congregational Native Church of Fort Beaufort and Blinkwater, is reported to have calmed the panicked men by raising his arms aloft and crying out in a loud voice:

"Be quiet and calm, my countrymen. What is happening now is what you came to do...you are going to die, but that is what you came to do. Brothers, we are drilling the death drill. I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers...Swazis, Pondos, Basotho...so let us die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war-cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our assegais in the kraal, our voices are left with our bodies."[10]

The damaged Darro did not stay to assist, but Brisk lowered her boats, whose crews then rescued survivors.[11]

The investigation into the accident led to a formal hearing in summer 1917, held in Caxton Hall, Westminster. It opened on 24 July, sat for five days spread over the next fortnight, and concluded on 8 August.[12] The court found Darro's Master, Henry W Stump, guilty of "having travelled at a dangerously high speed in thick fog, and of having failed to ensure that his ship emitted the necessary fog sound signals."[13] It suspended Stump's licence for a year.

The reason for Stump's decision not to help Mendi's survivors has been a source of speculation. There is however no evidence of his state of mind or intention. Certainly Darro was vulnerable to attack by enemy submarines, both as a large merchant ship and having sustained damage that put her out of action for up to three months.[14]

Wreck site edit

In 1945 Mendi's wreck was known to be 11.3 nautical miles (21 km) off Saint Catherine's Light, but it was not positively identified until 1974.[15] The ship rests upright on the sea floor. She has started to break up, exposing her boilers.

In 2006 the Commonwealth War Graves Commission launched an education resource called "Let us die like brothers" to highlight the role played by black Southern Africans during the First World War. In death they are afforded the same level of commemoration as all other Commonwealth war dead.

In December 2006 English Heritage commissioned Wessex Archaeology to make an initial desk-based appraisal of the wreck. The project will identify a range of areas for potential future research and serve as the basis for a possible unintrusive survey of the wreck itself in the near future.[16] In 2017 the ship's bell was handed in anonymously to a BBC journalist.[17][18] The Prime Minister, Theresa May returned the bell to South Africa while on an official visit there in August 2018.[19]

Monuments edit

This event is commemorated by monuments in South Africa, Britain, France and the Netherlands, as well as in the name of the port admin building at the Port of Ngqura, the eMendi Admin Building and the names of two South African Navy ships:

Monuments, ceremonies and other commemorations, such as artworks, in which the loss of men of the Mendi has been commemorated include:

- Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton, bearing the names of the men of the Mendi who had no known graves.[20][21]

- 13 men are buried in cemeteries in England, one in France and five are buried in Noordwijk in the Netherlands.[21][22]

- a memorial in the churchyard at Newtimber in West Sussex, England.[23]

- Mendi Memorial in Avalon Cemetery in Soweto, unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II on 23 March 1995.[24]

- Mendi Memorial in New Brighton, Port Elizabeth, South Africa.[21]

- Mendi memorial at the Gamothaga Resort in Atteridgeville, South Africa.[21]

- SS Mendi Memorial on an embankment at the Mowbray campus of the University of Cape Town, at the site where men of the South African Native Labour Contingent were billeted before embarking on the Mendi.[21] This is a sculpture by Cape Town artist Madi Phala that represents a ship's bow cast in heavy metal, sinking into the ground. In front of it are helmets, hats and discs, symbolising Mendi's troops, officers and crew. A plaque simply reads "SS Mendi, S. African troopship, sank next to the Isle of Wight 1917 02 21".[25] The wall was completed in 2014 with the names of all the men who were killed.[citation needed] The military had its first practice parade on 18 October 2014.[citation needed] In 2016 the South African Heritage Resources Agency declared the SS Mendi memorial as a national heritage site.[26]

- Delville Wood South African National Memorial has a bronze relief and panel bearing the names of men lost in Mendi.[21]

The Delville Memorial on the event of the 90th Anniversary of this tragedy held commemorative events there a Poem, a lament, written by the then South African High Commissioner to London Lindiwe Mabuza was read. Delville Memorial also has the SS Mendi Poem of S.E.K Mqhayi titles 'The Sinking of Mendi' which was originally written in isiXhosa.

- The bridge telegraph from the Mendi is at the Maritime Museum, Bembridge, on the Isle of Wight.[21]

- The Order of Mendi for Bravery, bestowed by the President of South Africa on citizens who have performed extraordinary acts of bravery.[21]

- A wreath laying ceremony was held on 23 August 2004 when the SAS Mendi and the Royal Navy Type 42 destroyer HMS Nottingham, met at the position where Mendi sank.[21]

- In 2006 the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and History Channel released a 20-minute film, Let Us Die Like Brothers, about the Mendi sinking and the involvement of black Southern Africans in the European theatre of the First World War.[21]

- On 21 July 2007 a ceremony was held at the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton, followed by SAS Mendi laying a wreath at sea where the ship sank.[21]

- In March 2009 the UK Ministry of Defence designated Mendi's wreck site as a protected war grave, thanks to a campaign by retired British Army Major Ned Middleton.[27][28]

- A painted triptych, The loss of the Mendi, by Hilary Graham, at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Art Museum, Port Elizabeth.[21]

- An animated short film Off the record by Wendy Morris, 2008 Artist in Residence, In Flanders Fields Museum.[29]

- BBC Radio 4 broadcast a radio documentary, The Lament of the SS Mendi, on 19 November 2008. Scots poet Jackie Kay studied the history of the sinking and recited her own memorial poem.[30]

- Several websites including those of the British Council,[31] the Commonwealth War Graves Commission,[32] Wessex Archaeology[16] and Delville Wood.[21]

- A commemorative white life-belt labelled "SS Mendi 21-02-1917", on public display at Simonstown's quayside in South Africa, next to the popular "Just Nuisance" dog statue.

- A 23-minute film African Kinship Systems: Emotional Science – Case Study #2: The Fate of the SS Mendi by filmmaker and visual anthropologist Dr Shawn Sobers was shown at the Royal West Academy (RWA) from 10 to 31 August 2014. Sobers' exhibition included the film, an alcohol libation offering, and a screen-based text piece presenting names of all the 646 men who died on the Mendi. The work was exhibited as part of RWA's "Re-Membering" series presenting commissioned artists responses to the First World War.[33]

- War memorial (next to Parliament of Botswana) in Gaborone, Botswana[34]

100th anniversary commemorative events edit

- A special memorial service marking the 100th Anniversary of the disaster was held in Portsmouth on Tuesday 21 February 2017.

- A memorial service was held at the memorial in the churchyard at Newtimber near Brighton, where some of the dead are buried, on 19 February 2017.[35]

- On 20 February 2017, a memorial ceremony to mark the 100th anniversary was held at Hollybrook Cemetery in Southampton which was attended by The Princess Anne.[36]

- A poem titled Waters of Wars Unknown was penned by South African Catholic cleric, writer and poet Fr Lawrence Mduduzi Ndlovu to mark the 100th Anniversary. It was published in the Huffington Post South Africa on the 100th Anniversary of the Sinking of the SS Mendi.[37]

- From Friday 29 June - Saturday 14 July 2018, Nuffield Southampton Theatres, NST City presented the world première of the play SS Mendi, Dancing the Death Drill, based on a book by Fred Khumalo.[38]

- On 8 August 2017, to coincide with the 100-year anniversary, a commemorative granite plaque was placed at the wreck site by a team led by the chairman of the English branch of the Legion of South African military veterans, Claudio Chistè.[39] The plaque contains a dedication.[40]

See also edit

- HMS Otranto – Armed merchant cruiser requisitioned by the Royal Navy in 1914

- List of disasters in Great Britain and Ireland by death toll

- List of maritime disasters in World War I

References edit

- ^ "Steamer for West African Trade". Glasgow Herald. No. 146, 123rd year. 20 June 1905. p. 9.

- ^ a b "Mendi". Clyde-built Ship Database. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Dancing the death drill: The sinking of the SS Mendi". BBC News. 21 February 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ a b "The sinking of SS Mendi: an avoidable tragedy". The National Archives blog. 21 February 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Board of Trade 1917, p. 7.

- ^ South African National Defence Force Archive

- ^ "Memorial wreath laying for the SS Mendi and her crew". South African Navy. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2006.

- ^ Record Card at South African National Defence Force Archive

- ^ "Isaac Wauchope Dyobh". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Boon, Mike (2008). The African Way: The Power of Interactive Leadership. Zebra. ISBN 978-1-77007-310-4.

- ^ SA Legion – Atteridgeville Branch. "The SS Mendi – A Historical Background". South African Navy. Navy News. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ Board of Trade 1917, p. 1.

- ^ Swinney, G (9 December 2007). "The Sinking of the SS Mendi, 21 February 1917". Military History Journal. 10 (1). The South African Military History Society. Archived from the original on 1 July 2003. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ Nicol 2001, p. 229.

- ^ "SS Mendi: The Legacies". Wessex Archaeology. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ^ a b "The Wreck of the SS Mendi". Wessex Archaeology. 1 May 2008.

- ^ "SS Mendi: WW1 shipwreck's bell 'recovered' in Swanage". BBC Online. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ Morris, Michael (17 June 2017). "SS Mendi's bell surfaces". IOL. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "SS Mendi: WW1 shipwreck's bell returned to South Africa by Theresa May". BBC News. 28 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ "Monuments of the First and Second World Wars". Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada.[clarification needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Sinking of the Mendi". Delville Wood.

- ^ "Het vergaan van de SS Mendi: Zuid-Afrikaanse oorlogsgraven in Noordwijk | Zuid-Afrikahuis". zuidafrikahuis.nl. Retrieved 5 March 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Newtimber | THE DOWNLAND BENEFICE". Archived from the original on 25 December 2013.

- ^ "The Mendi Memorial at Avalon Cemetery in Soweto". Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "SS Mendi sculpture part of UCT". Monday Paper Archives. University of Cape Town. 7 May 2007.

- ^ MG Digital (31 December 2016). "SS Mendi and Sharpville massacre named as new heritage sites". DispatchLive. East London Daily Dispatch. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "Retired Army major wins campaign to get sunken South African warship classed as official grave". The Daily Telegraph. 18 March 2009.

- ^ "Disasters at sea: the loss of the troopship Mendi". Archived from the original on 18 January 2006.

- ^ Morris, Wendy. 2008. Off the record. In Flanders Fields Museum, Ieper, Belgium.

- ^ Kay, Jackie. "The Lament of the SS Mendi". BBC.

- ^ Young, Baroness Lola (31 October 2014). "The hidden history of the sinking of the SS Mendi". Voices. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ "South African War Dead Honoured through New Technology". News. CWGC. 27 November 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ "A look at Re-Membering I". Behind the scenes. RWA. 14 August 2014.

- ^ Laverick, Jonathan (4 May 2015). The Kalahari Killings: The True Story of a Wartime Double Murder in Botswana, 1943. History Press. ISBN 9780750964593.

- ^ "SS Mendi tragedy commemorated in Sussex 100 years on". BBC News. 19 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "Princess Anne marks SS Mendi tragedy in Southampton". BBC. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "On The Centenary of the Sinking of the SS Mendi". Huffington Post South Africa. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "SS MENDI DANCING THE DEATH DRILL". Nuffield Southampton Theatres. Archived from the original on 21 January 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Let us die like brothers … the silent voices of the SS Mendi finally heard". The Observation Post: South African Modern Military History. 12 February 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Riddin, Tyler (28 August 2017). "Team braves rough waters to place plaque in honour of the SS Mendi". Daily Dispatch. Retrieved 4 January 2022 – via Pressreader.com.

Sources and further reading edit

- "Mendi" and "Darro" (PDF). London: Board of Trade. 2 October 1917. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Clothier, Norman (1987). Black Valour – The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916–1918 and the Sinking of the Mendi. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press. ISBN 0-86980-564-9.

- Nicol, Stuart (2001). MacQueen's Legacy; Ships of the Royal Mail Line. Vol. Two. Brimscombe Port and Charleston, SC: Tempus Publishing. p. 229. ISBN 0-7524-2119-0.

- Tracey, Hugh (1948). 100 Zulu Lyrics. African Music Society. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- "They died like warriors: tale of the SS Mendi". The Independent. 21 July 2007.

- Gribble, John; Scott, Graham (16 February 2017). We Die Like Brothers: The Sinking of the SS Mendi. London: Historic England Publishing. ISBN 978-1848023697.

- "We die like brothers": The sinking of the SS Mendi. History Extra

- "The Wreck of the SS Mendi: project pages". Wessex Archaeology. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

50°28′0″N 1°33′0″W / 50.46667°N 1.55000°W