Summary

Sherlock Holmes is a four-act play by William Gillette and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, based on Conan Doyle's character Sherlock Holmes. After three previews it premiered on Broadway November 6, 1899, at the Garrick Theatre in New York City.

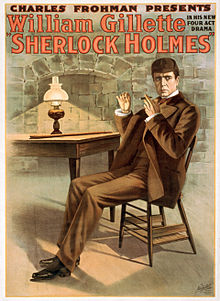

| Sherlock Holmes | |

|---|---|

Promotional poster of the play | |

| Written by | William Gillette Sir Arthur Conan Doyle |

| Characters | Sherlock Holmes Dr. Watson |

| Date premiered | October 23, 1899 |

| Place premiered | Star Theatre, Buffalo, New York, US |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | Drama |

| Setting | London, England |

Background edit

Recognizing the success of his character Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle decided to pen a play based on him.[1]

American theatrical producer Charles Frohman approached Conan Doyle and requested the rights to Holmes. While nothing came of their association at that time, it did inspire Conan Doyle to pen a five-act play featuring Holmes and Professor Moriarty.[2] Upon reading the play, Frohman felt that it was unfit for production[2] and instead persuaded Conan Doyle that actor William Gillette would be an ideal Holmes[1] and would also be the perfect person to rewrite the play.[2] Gillette, a successful playwright, donned a deerstalker and cape to visit Conan Doyle and request permission not only to perform the part but to rewrite it himself.[1]

Creation edit

The play itself drew material from Conan Doyle's published stories "A Scandal in Bohemia", "The Final Problem" and A Study in Scarlet,[2][1][3][4] while adding much that was new as well.[1] As the plot was largely taken from Doyle's canon, with some dialogue directly lifted from his original stories, Doyle was credited as a co-author, even though Gillette wrote the play.[1][3]

Gillette took great liberties with the character, such as giving Holmes a love interest. While Conan Doyle was initially uncomfortable with these additions, the success of the play softened his views;[1] he said, "I was charmed both with the play, the acting, and the pecuniary result."[3] Doyle later recounted how he had received a cable from Gillette inquiring, "May I marry Holmes?", to which Conan Doyle replied, "You may marry him, murder him, or do anything you like to him."[1][5] The love interest was modelled on Irene Adler's role in "A Scandal in Bohemia", with Gillette reinventing the character and renaming her "Alice Faulkner".[1]

Gillette's play features Professor Moriarty as the villain, but Gillette names him "Robert Moriarty".[6] At this point no forename had been given for Moriarty in Conan Doyle's stories.

Conan Doyle had mentioned an unnamed pageboy in "A Case of Identity", and Gillette utilized the character and christened him "Billy". Conan Doyle himself would later reintroduce the character into some Holmes stories and continue using the name Billy.[7]

Revisions edit

The text of the play was revised numerous times during its long series of runs. The original text of 1899 was revised with corrections in 1901. There was a further "corrected and expurgated text" of approximately 1923, and a final revision for the "farewell revival" of 1929–1930. When the play was published in book form (as opposed to a play script) by Doubleday, Doran & Company in 1935, further corrections were made, as described by Vincent Starrett in his introduction:

These have been carefully collated and separate scenes and situations of still other corrected versions also have been examined. Finally, Mr. Gillette has been frequently consulted. ... As made by Mr. Gillette, between seasons or between revivals, the changes were intended to lend speed or effectiveness to the drama as seen and heard by a theatre audience. Long speeches were made into short ones, and some were dropped entirely; references that had little or no bearing on the swift and chronological development of the narrative were eliminated. Now that the play is intended to be read, it has seemed well to replace some of the lines earlier removed, and to eliminate certain later substitutions. In short, the play as now published is believed to be an intelligent blend or fusion of all previous texts, containing the best of each. Stage directions—lights—position—business—with which all existing manuscripts are bursting, have been held to a minimum.[8]

Production edit

Sherlock Holmes was first seen at the Star Theatre in Buffalo, New York, October 23, 1899. After three previews it opened November 6, 1899, at the Garrick Theatre in New York City.[9] The four-act drama was produced by Charles Frohman, with incidental music by William Furst and scenic design by Ernest Gros.[10] Novel for its time, the production made scene changes with lighting alone.[11]

Cast edit

- William Gillette as Sherlock Holmes[11]

- Bruce McRae as Doctor Watson[11]

- Reuben Fax as John Forman[11]

- Harold Heaton as Sir Edward Leighton[11]

- Alfred S. Howard as Count Von Stahlburg[11]

- George Wessells as Professor Moriarty[11]

- Ralph Delmore as James Larrabee[11]

- George Honey as Sidney Prince[11]

- Henry Herman as Alfred Bassick[11]

- Thomas McGrath as Jim Craigin[11]

- Elwyn Eaton as Thomas Leary[11]

- Julius Wyms as "Lightfoot" McTague[11]

- Henry S. Chandler as John[11]

- Soldene Powell as Parsons[11]

- Henry McArdle as Billy[11]

- Katherine Florence as Alice Faulkner[11]

- Jane Thomas as Mrs. Faulkner[11]

- Judith Thomas as Madge Larrabee[11]

- Hilda Englund as Thérese[11]

- Kate Ten Eyck as Mrs. Smeedley[11]

The play ran at the Garrick for more than 260 performances[4] before a long tour of the United States.[9]

Sherlock Holmes moved on to London's Lyceum Theatre in September 1901.[1][4] During the London leg of the tour, a 13-year-old Charlie Chaplin played Billy the pageboy.[4][7][12] The play finally closed after 200 performances.[4] In 1903, H. A. Saintsbury took over the role from Gillette for a tour of Great Britain.[9] Between this play and Conan Doyle's own stage adaptation of "The Adventure of the Speckled Band", Saintsbury portrayed Holmes over 1,000 times.[13]

A burlesque of the play, Sheerluck Jones, or Why D’Gillette Him Off opened at Terry's Theatre in 1901 with Clarence Blakiston in the title role and ran for 138 performances.[14][15]

Revivals edit

Gillette revived Sherlock Holmes in 1905, 1906, 1910, and 1915.[4] Gillette returned for a 45-performance run in 1929.[16]

In 1928 there was another brief Broadway revival with Robert Warwick as Holmes, Stanley Logan as Watson and Frank Keenan as Moriarty. The production opened February 20, 1928, at the Cosmopolitan Theatre in New York City, and ran for 16 performances.[17]

The Royal Shakespeare Company revived the play in 1973.[18] Directed by Frank Dunlop and starring John Wood as Holmes, the play was a huge success,[18] which led to a move to Broadway in November 1974[19] and a subsequent tour.[18] By the end of its Broadway run, the play had been performed 471 times.[19] Wood was succeeded as Holmes by John Neville,[2] Robert Stephens,[2] and Leonard Nimoy;[18] the first two had both played the detective before (Neville in A Study in Terror and Stephens in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.) Dunlop was nominated for a Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Director of a Play.[20]

In 1976, the play was performed at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, the cast included Alan Rickman as Sherlock Holmes and David Suchet as Professor Moriarty.[21]

Frank Langella first performed the part in 1977 at the Williamstown Theatre Festival in Massachusetts.[22] He took on the role once more for a production taped for HBO's Standing Room Only program in 1981.[22] This would be only the second theater production to be undertaken by HBO.[22]

Adaptations edit

In 1916, a silent film of the play also entitled Sherlock Holmes featured William Gillette in the role of Holmes and has been called "the most elaborate of the early movies".[23] It is one of the earliest American film adaptations of the Holmes character. Long thought to be a lost film, a print of the film was found in the Cinémathèque Française's collection in October 2014.[24] It was restored and screened in 2015.

The play was once again filmed in 1922, this time with John Barrymore donning the deerstalker.[25] 1932 brought another adaptation of Gillette's play, with Clive Brook taking over the role in Sherlock Holmes.[26]

On September 25, 1938, Orson Welles starred in his own radio adaption of Sherlock Holmes for The Mercury Theatre on the Air. The cast included Ray Collins as Dr. Watson, Mary Taylor as Alice Faulkner, Brenda Forbes as Madge Larrabee, Edgar Barrier as James Larrabee, Morgan Farley as Inspector Forman, Richard Wilson as Craigin, Alfred Shirley as Bassick, William Alland as Leary, Arthur Anderson as Billy, and Eustace Wyatt as Professor Moriarty. Music was conducted by Bernard Herrmann.[27][28][29]

The 1939 film The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, the second film to star Basil Rathbone as Holmes and Nigel Bruce as Watson, is credited as an adaptation of the play, though they bear little resemblance.[30]

In 1953, BBC Home Service dramatized the play with Carleton Hobbs as Holmes and Norman Shelley as Watson.[31]

In 1979 composer Raimonds Pauls and songwriter, poet Jānis Peters wrote a musical Šerloks Holmss. It premiered in Riga, Latvia's Dailes Theatre with Valentīns Skulme as Holmes and Gunārs Placēns as Watson.[32] There was a 2006 revival, again in Dailes Theatre.

Cultural impact edit

Gillette's Holmes is widely credited with being the first to utter "Elementary, my dear Watson"[2][7]—a phrase that never appears in Conan Doyle's stories.[33]

It was also Gillette who introduced the famous curved pipe as a trademark Holmes prop.[7]

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 34. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bunson, Matthew (1994). Encyclopedia Sherlockiana: an A-to-Z guide to the world of the great detective. Macmillan. pp. 228–230. ISBN 978-0-671-79826-0.

- ^ a b c Starrett, Vincent (1993). The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Otto Penzler Books. p. 140. ISBN 1-883402-05-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Dick Riley; Pam McAllister (1998). The Bedside, Bathtub & Armchair Companion to Sherlock Holmes. Continuum. pp. 60. ISBN 0-8264-1116-9.

- ^ Starrett, Vincent (1993). The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Otto Penzler Books. p. 139. ISBN 1-883402-05-0.

- ^ Starrett, Vincent (1993). The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Otto Penzler Books. p. 141. ISBN 1-883402-05-0.

- ^ a b c d Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 39. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Gillette, William (1935). Sherlock Holmes: A Play. Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc. pp. xv–xvi. OCLC 1841327.

- ^ a b c Kabatchnik, Amnon (2008). Sherlock Holmes on the Stage: A Chronological Encyclopedia of Plays. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 9781461707226.

- ^ "Sherlock Holmes". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Dramatic and Musical: William Gillette as Conan Doyle's Wonderful Detective". The New York Times. 8 November 1899. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Starrett, Vincent (1993). The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Otto Penzler Books. p. 142. ISBN 1-883402-05-0.

- ^ Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 57. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Marvin Lachman, The Villainous Stage: Crime Plays on Broadway and in the West End, MacFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers (2014) - Google Books pg. 30]

- ^ Clarence Blakiston on Historical & Fictional Characters in Sherlockian Pastiches - Sherlockian Theatre

- ^ Cartmell, Van H.; Cerf, Bennett, eds. (1946). Famous Plays of Crime and Detection. Philadelphia: The Blakiston Company. pp. x.

- ^ "Sherlock Holmes". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 116. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ a b Boström, Mattias (2018). From Holmes to Sherlock. Mysterious Press. p. 373. ISBN 978-0-8021-2789-1.

- ^ "1974-1975 21st Drama Desk Awards". Drama Desk Award. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ "See how Alan Rickman wowed Birmingham Rep as Sherlock Holmes before he found fame". Birmingham Live. 16 January 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ a b c "HBO offers Sherlock Holmes". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ Phil Hardy, The BFI companion to crime (British Film Institute, 1997), p. 168

- ^ Andrew Pulver; Kim Willsher (2 October 2014). "'Holy grail' of Sherlock Holmes films discovered at Cinémathèque Française". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ Joseph W. Garton, The film acting of John Barrymore (1980), p. 85

- ^ Robert W. Pohle, Douglas C. Hart, Sherlock Holmes on the Screen: The Motion Picture Adventures of the World's Most Popular Detective (A. S. Barnes, 1977), pp. 100, 111, 113

- ^ Welles, Orson; Bogdanovich, Peter; Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1992). This is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 346. ISBN 0-06-016616-9.

- ^ Orson Welles on the Air: The Radio Years. Catalogue for exhibition October 28 – December 3, 1988. New York: The Museum of Broadcasting. 1988. p. 51.

- ^ "Sherlock Holmes". Orson Welles on the Air, 1938–1946. Indiana University Bloomington. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ "The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ DeWaal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. p. 383. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- ^ "Atceramies izrādi "Šerloks Holms"". lr2.lsm.lv. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Boström, Mattias (2018). From Holmes to Sherlock. Mysterious Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8021-2789-1.

External links edit

- Sherlock Holmes: A Play at the Internet Archive

- The text of the play at the Diogenes Club Library site (archived)

- Sherlock Holmes (1916) at IMDb

- Sherlock Holmes (1981) at IMDb