Summary

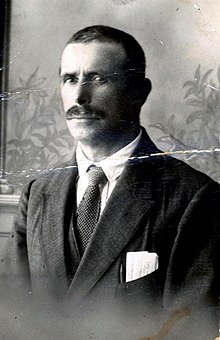

Shmuel Cohen (1870–1940) composed the music for the Israeli national anthem, the "Hatikvah" - "The Hope".

Biography edit

Samuel (Shmuel) Cohen was born in a small town near Ungheni, Moldavia, then part of the Russian Empire. Motivated by a rising tide of Russian state-sponsored antisemitism and terrorism (pogroms), Cohen immigrated to Ottoman Palestine in 1887. He settled in Rishon LeZion ("First to Zion") as part of the Hovevei Zion ("Lovers of Zion") movement. Rishon LeZion was established in 1882, as a Jewish agricultural cooperative on barren land purchased from two brothers, Musa and Mustafa el Dagani.

In Rishon LeZion, Cohen married Minya Papirmeister and made his living as a vintner. Cohen was an accomplished local violinist. He was given the nickname “Stempenu”, after the famous fictional klezmer violinist in Shalom Aleichem's book of the same name. In 1938, when Cohen wrote his biography, he titled it Stempenu.

Cohen was one of the founders of the first Keren Kayemet in Rishon LeZion in 1889. It predated the later national Keren Kayemet Le Yisrael, (Jewish National Fund for Israel).[1]

Cohen returned to Moldavia where he established a girls school in the early years of the 20th century. The school was not successful. He returned to Rishon LeZion, reestablishing himself as a vintner and settling permanently to raise his only child, Ida. Cohen was active in early Jewish settlement efforts in Palestine. He helped found the city of Rehovot. The effort was unique in that it did not involve financial support from Baron Edmond James de Rothschild. Philosophically, he joined with others working for the Redemption of the Ancient Land of Israel.[2][3]

HaTikvah edit

Naftali Herz Imber's poem "Tikvatenu" (Our Hope), published in 1886, stirred Jews everywhere, especially those who lived under antisemitic oppression. Cohen's brother had immigrated to Ottoman Palestine, settling in c. 1883 in Yesud HaMa'ala, the first modern Jewish community and moshava in the Hula Valley. He sent a copy of Imber's poem to Cohen in Moldavia.

Imber lived in Palestine for six years, where his poem was greeted with enthusiasm by the farmers of the Jewish settlements.[4] Cohen set the poem to music, based on a Moldavian/Romanian folk-song, "Carul cu boi" ("The Ox Cart"). The catalyst of Cohen's musical adaptation facilitated the enthusiastic spread of Imber's poem throughout the Zionist communities of Palestine. Within a few years, it spread globally to pro-Zionist communities and organizations, becoming the unofficial Zionist anthem. In 1933, at the 18th Zionist Congress in Prague, it was formally adopted and renamed "Hatikvah" ("The Hope").

The Hatikvah widely permeated Jewish popular culture, promoted by famous singers such as the American Al Jolson.[5]

Hatikvah was sung even outside the gas chambers.[6] The British military made the most famous recording of the Hatikvah, when it was sung by survivors of the Bergen Belsen Concentration Camp.[7] The Holocaust survivors onboard the famed American rescue ship, the SS Exodus, sang the Hatikvah as it pulled into the port of Haifa.[8] The British arrested the Holocaust survivors and returned them to Germany for reinternment in DP camps.[2][3]

British Mandate authorities banned the singing or musical broadcasting of Hatikvah, as it was considered provocative. A similar piece, Smetana's The Moldau, with its musical refrains reminiscent of Cohen's Hatikvah composition, was substituted for broadcast media by Zionist communities in Palestine. May 14, 1948, Hatikvah was played at the conclusion of the Israeli Declaration of Independence ceremony. November 2004, Imber-Cohen's Hatikvah was formally adopted through Israel's Flag, Coat-of-Arms, and National Anthem Law.

Death edit

Cohen died on March 28, 1940. He was buried in the (Old) Rishon LeZion Cemetery. In 2020, after years of neglect, the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation restored Cohen's and his wife Mina's gravesites per agreement with Rishon LeZion to reflect the original historic interment style. A sculpture was added in the form of a flame with a Star of David emerging from the middle. A musical clef is welded to the star. The sculpture was created by Israeli sculptor Sam Philipe who constructed the flame from metal fragments of Qassem rockets fired into Israel from the Gaza Strip.

References edit

- ^ "Our History". Keren Kayemet Le Yisrael/Jewish National Fund (KKL/JNF). Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b "מוזאון ראשון לציון – מוזאון לתולדות ראשון לציון" (in Hebrew). Rishon LeZion Museum. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b Yona Shapira, curator, Rishon LeZion Museum

- ^ Judaism: A Quarterly of Jewish Life and Thought, Vol. 5, No. 2, Spring 1956, p.149

- ^ Owen Nicholson (16 June 2017). "Al Jolson, Hatikvah". Youtube. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "The History of Hatikvah". 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Hatikva at Bergen-Belsen". Youtube. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Exodus 1947: History in the Making". Israel Forever Foundation. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

External links edit

Media related to Shmuel Cohen at Wikimedia Commons

- "Hatikvah: Conceptions, Receptions and Reflections | המרכז לחקר המוסיקה היהודית". www.jewish-music.huji.ac.il. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Latest Updates". ReformJudaism.org. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Obituary Samuel Cohen, Haboker Palestine Newspaper, April 14, 1940

- [1]

- Biography Samuel Cohen, November 1938, (Hebrew) published in the Bustanei, (the Farmers of the Land of Israel), Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem.

- "The Second Death of Shmuel Cohen, the Hatikvah's Composer".

- "Hatikvah, the National Anthem of Israel". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Hatikva - National Anthem of the State of Israel". knesset.gov.il. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Zion, Ilan Ben. "How an unwieldy romantic poem and a Romanian folk song combined to produce 'Hatikva'". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 25 May 2020.