Summary

Space Harrier[a] is a third-person arcade rail shooter game developed by Sega and released in 1985. It was originally conceived as a realistic military-themed game played in the third-person perspective and featuring a player-controlled fighter jet, but technical and memory restrictions resulted in Sega developer Yu Suzuki redesigning it around a jet-propelled human character in a fantasy setting. The arcade game is controlled by an analog flight stick while the deluxe arcade cabinet is a cockpit-style linear actuator motion simulator cabinet that pitches and rolls during play, for which it is referred as a taikan (体感) or "body sensation" arcade game in Japan.

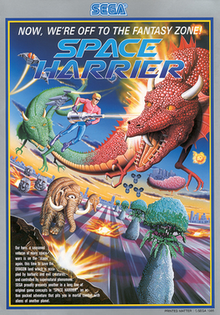

| Space Harrier | |

|---|---|

European arcade flyer | |

| Developer(s) | Sega |

| Publisher(s) | Sega |

| Designer(s) | Yu Suzuki |

| Composer(s) | Hiroshi Kawaguchi Yu Suzuki Yuzo Koshiro (X68000) Mark Cooksey (C64) |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | October 2, 1985

|

| Genre(s) | Rail shooter |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

| Arcade system | Space Harrier hardware[6] |

It was a commercial success in arcades, becoming one of Japan's top two highest-grossing upright/cockpit arcade games of 1986 (along with Sega's Hang-On).[7] Critically praised for its innovative graphics, gameplay and motion cabinet, Space Harrier is often ranked among Suzuki's best works. It has made several crossover appearances in other Sega titles, and inspired a number of clones and imitators, while Capcom and PlatinumGames director Hideki Kamiya cited it as an inspiration for his entering the video game industry.

Space Harrier has been ported to over twenty different home computer and gaming platforms, either by Sega or outside developers such as Dempa in Japan and Elite Systems in North America and Europe. Two home-system sequels followed in Space Harrier 3-D and Space Harrier II (both released in 1988), and the arcade spin-off Planet Harriers (2000). A polygon-based remake of the original game was released by Sega for the PlayStation 2 as part of their Sega Ages series in 2003.

Gameplay edit

Space Harrier is a fast-paced rail shooter game played in a third-person perspective behind the protagonist,[8] set in a surreal world composed of brightly colored landscapes adorned with checkerboard-style grounds and stationary objects such as trees or stone pillars. At the start of gameplay, players are greeted with a voice sample speaking "Welcome to the Fantasy Zone. Get ready!", in addition to "You're doing great!" with the successful completion of a stage.[9] The title player character, simply named Harrier,[note 1] navigates a continuous series of eighteen distinct stages[13] while utilizing an underarm jet-propelled laser cannon that enables Harrier to simultaneously fly and shoot. The objective is simply to destroy all enemies—who range from prehistoric animals and Chinese dragons to flying robots, airborne geometric objects and alien pods—all while remaining in constant motion in order to dodge projectiles and immovable ground obstacles.[9]

Fifteen of the game's eighteen stages contain a boss at the end that must be killed in order to progress to the next level;[14] the final stage is a rush of seven past bosses encountered up to that point that appear individually and are identified by name at the bottom of the screen.[13] The two other levels are bonus stages that contain no enemies and where Harrier mounts an invincible catlike dragon named Uriah,[9][note 2] whom the player maneuvers to smash through landscape obstacles and collect bonus points. After all lives are lost, players have the option of continuing gameplay with the insertion of an extra coin.[17] As Space Harrier has no storyline, after the completion of all stages, only "The End" is displayed before the game returns to the title screen and attract mode, regardless of how many of the player's extra lives remain.[17]

Development edit

The market research department told me not to make the game. I asked them why [3D shooters] didn't succeed and they told me it was because the target is too small. Based on that, my conclusion was that I basically had to make sure the player could hit the target. So, I made a homing system that guaranteed that the target could be hit. When the target was close, it would always hit, but when the target was in the distance, the player would miss. So the result of whether the player would hit the target or not was determined the second the player took the shot.

The game was first conceived by a Sega designer named Ida,[18] who wrote a 100-page document proposing the idea of a three-dimensional shooter that contained the word "Harrier" in the title.[18] The game would feature a player-controlled fighter jet that shot missiles into realistic foregrounds, a concept that was soon rejected due to the extensive work required to project the aircraft realistically from varying angles as it moved around the screen,[18] coupled with arcade machines' memory limitations.[19] Sega developer Yu Suzuki therefore simplified the title character to a human, which required less memory and realism to depict onscreen.[19] He then rewrote the entire original proposal, changing the style of the game to a science-fiction setting while keeping only the "Harrier" name.[18] His inspirations for the game's new design were the 1984 film The Neverending Story, the 1982 anime series Space Cobra, and the work of artist Roger Dean.[19] Certain enemies were modelled on characters from the anime series Gundam.[20] Suzuki included a nod to the original designer in the finished product with an enemy character called Ida, a large moai-like floating stone head, because the designer "had a really big head".[18] Three different arcade cabinets were produced: an upright cabinet, a sit-down version with a fixed seat, and its best known[12][21][22] incarnation: a deluxe cockpit-style rolling cabinet that was mounted on a motorised base and moved depending on the direction in which players pushed the joystick. Sega was hesitant to have the cabinets built due to high construction costs; Suzuki, who had proposed the cabinet designs, offered his salary as compensation if the game failed, but it would instead become a major hit in arcades.[23]

Suzuki had little involvement with the game after its initial release: the Master System port was developed by Mutsuhiro Fujii and Yuji Naka, and they added a final boss and an ending sequence which were included in subsequent ports. The game was too successful for Sega to abandon the series, and other Sega staff, such as Naoto Ohshima (character designer for Sonic the Hedgehog), Kotaro Hayashida (planner of Alex Kidd in Miracle World), and Toshihiro Nagoshi (director of Super Monkey Ball) have had involvement in various sequels. In a 2015 interview, Suzuki said that he would have liked to create a new Space Harrier by himself, and was pleased to see it ported to the Nintendo 3DS.[20]

Hardware edit

Space Harrier was one of the first arcade releases to use 16-bit graphics and scaled sprite ("Super Scaler") technology[24] that allowed pseudo-3D sprite scaling at high frame rates,[25] with the ability to display 32,000 colors on screen.[26] Running on the Sega Space Harrier arcade system board[27] previously used in Suzuki's 1985 arcade debut Hang-On, pseudo-3D sprite/tile scaling is used for the stage backgrounds while the character graphics are sprite-based.[25] Suzuki explained in 2010 that his designs "were always 3D from the beginning. All the calculations in the system were 3D, even from Hang-On. I calculated the position, scale, and zoom rate in 3D and converted it backwards to 2D. So I was always thinking in 3D".[28]

The game's soundtrack is by Hiroshi Kawaguchi, who composed drafts on a Yamaha DX7 synthesizer and wrote out the final versions as sheet music, as he had no access to a "real" music sequencer at the time.[29] A Zilog Z80 CPU powering both a Yamaha YM2203 synthesis chip and Sega's PCM unit that was used for audio and digitized voice samples.[12][29] Space Harrier utilized an analog flight stick as its controller that allowed onscreen movement in all directions, while the velocity of the character's flight is unchangeable. The degree of push and acceleration varies depending on how far the stick is moved in a certain direction.[26] Two separate "fire" buttons are mounted on the joystick (a trigger) and on the control panel; either one can be pressed repeatedly in order to shoot at enemies.

The deluxe arcade cabinet is a cockpit-style motion simulator cabinet that pitches and rolls during play, for which it is referred to as a taikan ("body sensation") arcade game in Japan.[30][31] It is often mistakenly referred to as a hydraulic cabinet, as a pair of motorized linear actuators in the base tilted the cabinet in two axes.[citation needed]

Ports edit

Space Harrier has been ported to numerous home computer systems and gaming consoles, with most early translations unable to reproduce the original's advanced visual or audio capabilities while the controls were switched from analog to digital.[9] The first port was released in 1986 for the Master System (Mark III in Japan), developed by Sega AM R&D 4.[32] The first two-megabit cartridge produced for the console,[5] the game was given a plot in which Harrier saves the "Land of the Dragons" (rather than the "Fantasy Zone") from destruction, with a new ending sequence in contrast to the arcade version's simple "The End" message.[9][14][33] All eighteen stages were present but the backdrops therein were omitted, leaving just a monochromatic horizon and the checkerboard floors. An exclusive final boss was included in a powerful twin-bodied fire dragon named Haya Oh, who was named after then-Sega president Hayao Nakayama.[9] The 1991 Game Gear port is based on its Master System counterpart, but with redesigned enemies and only twelve stages,[9] while Rutubo Games produced a near-duplicate of the arcade version in 1994 for the 32X add-on for the Sega Genesis.[33] Both games featured box art by Marc Ericksen.[34]

Other releases were developed for non-Sega gaming systems such as the TurboGrafx-16 and the Famicom, while Europe and North America saw 8-bit home computer ports by Elite Systems for the ZX Spectrum,[35][36] Amstrad CPC and Commodore 64 in 1986, and later in 1989 for the 16-bit Amiga and Atari ST. The Commodore 64 received two conversions, one originating in the UK and the other from the USA.[9][12]

M2, in collaboration with Sega CS3, ported Space Harrier to the handheld Nintendo 3DS console in 2013, complete with stereoscopic 3D and widescreen graphics—a process that took eighteen months.[37][38][39] Sega CS3 producer Yosuke Okunari described the game's 3D-conversion process as "almost impossible. When you take a character sprite that was originally in 2D and bring it into a 3D viewpoint, you have to build the graphic from scratch".[40] During development, M2 president Naoki Horii sought opinions from staff members regarding the gameplay of the arcade original: "They'd say it was hard to tell whether objects were right in front of their character or not. Once we had the game in 3D, the same people came back and said, 'OK, now I get it! I can play it now!'"[40] The port included a feature that allowed players to use the 3DS's gyroscope to simulate the experience of the original motorised cabinet by way of a tilting screen,[41] compounded by the optional activation of the sounds of button clicks and the cabinet's movement.[42] Horii recalled in a 2015 interview that he was intrigued by the possibility of crafting Space Harrier and past Sega arcade games for the 3DS using stereoscopic technology: "Both SEGA and M2 wanted to see what would happen if we added a little bit of spice to these titles, in the form of modern gaming technology. Would it enhance the entertainment factor? I think the reception that the releases have had from critics highlights that these games are as relevant today as ever, and that means we've succeeded".[43]

Reception edit

| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 70/100 (3DS)[44] 74/100 (Switch)[45] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | 4.5/5 (32X)[46] 2.5/5 (PC)[8] 4.5/5 (SMS)[47] 3/5 (T16)[48] 3/5 (Wii)[49] |

| Crash | 77% (ZX)[51] |

| Computer and Video Games | Positive (arcade)[31] 82% (Amiga)[52] 35/40 (CPC)[53] 78% (SMS)[54] 89% (T16)[55] 34/40 (ZX)[53] |

| GamePro | 4/5 (32X)[56] |

| GameSpy | 9/10 (SMS)[57] |

| IGN | 4.5/10 (Wii)[58] |

| Micromanía | 8/10 (SMS)[59] |

| Next Generation | 3/5 (32X)[50] |

| Sinclair User | Positive (arcade)[60] 5/5 (ZX)[35] |

| Tilt | 16/20 (SMS)[61] |

| Your Sinclair | 9/10 (ZX)[36] |

| Zzap!64 | 85% (Amiga)[62] |

| Computer Gamer | Positive (arcade)[63] |

| Gamest | 19/24 (arcade)[64] |

Arcade edit

The game was commercially successful upon its initial arcade release. Sega unveiled Space Harrier at the 1985 Amusement Machine Show in Japan, where it was the most popular game.[65] In January 1986, Game Machine listed Space Harrier as being the top-grossing title on the monthly upright/cockpit arcade cabinet charts in Japan.[66] It remained at the top of the upright/cockpit arcade charts for much of 1986, through February,[67][68] March[69][70] and early April,[71] then returning to the top in May,[72][73] remaining at the top through June,[74][75] July[76][77] and August,[78] and then topping the charts again in October.[79] Overall, the Space Harrier rolling type cabinet was Japan's second highest-grossing upright/cockpit arcade cabinet during the first half of 1986 (below only Hang-On),[80] and the overall highest-grossing upright/cockpit arcade game during the latter half of 1986.[81] It was later Japan's seventh highest upright/cockpit arcade game of 1987.[7]

The arcade game was positively received by critics upon release. Reviewing the game at the 1986 Amusement Trades Exhibition International in London, Clare Edgeley of Computer and Video Games hailed it as a "crowd stopper" due to its "realistic" moving cockpit, graphical capabilities and "amazing technicolour landscapes" but cautioned: "Unless you are an expert, you will find it very difficult".[31] Mike Roberts of Computer Gamer magazine praised the "extremely good" graphics, the "quite good" 3D effects, and the cockpit simulator cabinet.[63] The July 1986 issue of Japanese magazine Gamest ranked Space Harrier at number one on its list of best Sega arcade games.[64]

Ports edit

The game was also positively received upon its home releases. The home computer conversion of Space Harrier was in the top five of the UK sales chart in December 1986,[82] and was tied as runner-up with the Commodore 64 title Uridium for Game of the Year honors at the 1986 Golden Joystick Awards.

Ed Semrad of The Milwaukee Journal gave the Master System port a 9/10 rating,[83] and Computer Gaming World deemed it "the best arcade shoot-'em-up of the year ... as exciting a game as this reviewer has ever played".[84] Phil Campbell of The Sydney Morning Herald praised the 1989 Amiga conversion as "absorbing" and "a faithful copy of the original".[85] Computer and Video Games called the port "an entirely unpretentious computer game full of weird and wacky nasties".[52] Paul Mellerick of Sega Force wrote that the Game Gear version was "amazingly close to the original ... the scrolling's the speediest and smoothest ever seen".[86] GamePro commented that the 32X version had "straightforward controls", graphics relatively close to the arcade version, and was "a nice trip down memory lane",[56] while Next Generation dubbed it as decent, solid game.[50] AllGame called the game "a must-have" title for 32X system.[46]

Lucas Thomas of IGN rated the 2008 Wii port a 4.5 score out of 10, citing its "poor visuals and poor control" and "dulled" color palette.[58] Jeff Gerstmann of Giant Bomb, in his review of Sonic's Ultimate Genesis Collection, criticized the Space Harrier emulation's "numerous audio issues that make it sound completely different from the way the original game sounds".[87] Bob Mackey of USGamer was critical to Nintendo 3DS port.[42]

Retrospective edit

The game continues to garner praise for its audio, visual, and gameplay features.[10][88][89] GameSetWatch's Trevor Wilson remarked in 2006: "It's easy to see why the game is so well-loved to this day, with its blinding speed and classic tunes".[90] In 2008, Retro Gamer editor Darran Jones described the game as "difficult", but "a thing of beauty [that] even today ... possesses a striking elegance that urges you to return to it for just one more go".[91] That same year, IGN's Levi Buchanan opined: "Even today, Space Harrier is a sight to behold, a hellzapoppin' explosion of light, color, and imagination".[26] Eric Twice of Snackbar Games noted in 2013: "It's easy to just see it as just a game in which you press the button and things die, but Suzuki is a very conscious designer. He has a very specific vision behind each of his games, and nothing in them is ever left to chance".[92] In a 2013 Eurogamer retrospective on the series, Rich Stanton observed: "The speed at which Space Harrier moves has rarely been matched. It's not an easy thing to design a game around. Many other games have fast parts, or certain mechanics tied to speed—and it's interesting to note how many take control away at this point. Every time I play Space Harrier ... the speed blows me away one more time. It is a monster".[21]

Eric Francisco of Inverse described the game's visuals in 2015: "Imagine an acid trip through an '80s anime, a Robert Jordan novel, and early Silicon Valley binge coding sessions".[93] GamesRadar ranked the arcade original's bonus stage among the "25 best bonus levels of all time" in 2014, likening it to players piloting The Neverending Story's dragon character Falkor.[94] Kotaku named the Space Harrier tribute stage from Bayonetta in their 2013 selection of "the trippiest video game levels".[95] Also in 2013, Hanuman Welch of Complex included Space Harrier among the ten Sega games he felt warranted a "modern reboot", citing its "kinetic pace that would be welcome on today's systems".[96]

Legacy edit

Space Harrier spawned two home-system sequels in 1988. The Master System exclusive Space Harrier 3-D utilized Sega's SegaScope 3-D glasses, and featured the same gameplay and visuals as the port of the original game while containing new stage, enemy, and boss designs.[15] Space Harrier II was one of six launch titles for the Japanese debut of the Mega Drive (Sega Genesis),[97] and released as such in the United States in August 1989.[98] In December 2000, fifteen years after the original game's debut, Sega released the loose arcade sequel Planet Harriers, which again continued the gameplay style of the franchise but featured four new selectable characters each possessing distinct weapons, in addition to five fully realized stages and a new option of purchasing weapon power-ups.[97] However, Planet Harriers had only a minimal presence in the United States due to its faltering arcade scene, and it was never given a home release.[99] In 2003, a remake of the original Space Harrier was developed by Tamsoft as part of the Japanese Sega Ages classic-game series (Sega Classics Collection in North America and Europe) for the PlayStation 2.[100] The graphics are composed of polygons instead of sprites while several characters are redesigned, and a selectable option allows players to switch to a "fractal mode" that replaces the traditional checkerboard floors with texture-mapped playfields and includes two new underground stages.[9] Power-ups such as bombs and lock-on targeting fly toward and are caught by the player during gameplay.[101]

The original Space Harrier was packaged with three of Yu Suzuki's other works—After Burner, Out Run, and Super Hang-On—for the 2003 Game Boy Advance release Sega Arcade Gallery. The Space Harrier Complete Collection (Sega Ages 2500 Series Vol. 20: Space Harrier II in Japan),[102] developed by M2 for the PlayStation 2, followed on October 27, 2005 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the franchise,[103] and was composed of all the official series releases "to go with the various generations of our customers", according to Yosuke Okunari.[104] Bonus content included a record-and-replay feature and an arcade promotional-material gallery,[105] in addition to images of Hiroshi Kawaguchi's sheet music and notes for the original game's soundtrack.[106] The 1991 Game Gear port is hidden therein as an Easter egg.[100]

Space Harrier was re-released for Nintendo Switch, as part of the Sega Ages lineup.

Other appearances edit

Space Harrier has shared an unofficial connection with another Sega shooter franchise, Fantasy Zone, which debuted in Japanese arcades in March 1986.[107] Both series are believed to be set in the same universe;[26] Space Harrier's opening line of dialogue at the start of gameplay ("Welcome to the Fantasy Zone") has been cited as a reason, but this was dispelled by Fantasy Zone director Yoji Ishii in a 2014 interview.[30] A 1989 port of Fantasy Zone for the Japan-exclusive Sharp X68000 contains a hidden stage called "Dragon Land" that features Space Harrier enemy characters and is accessible only by following a specific set of instructions.[97] In 1991, NEC Avenue developed Space Fantasy Zone for the CD-ROM, featuring Fantasy Zone's main character Opa-Opa navigating nine levels of combined gameplay elements and enemies from both franchises. Despite a December 1991 preview in Electronic Gaming Monthly[108] and advertising designed by artist Satoshi Urushihara,[97] Space Fantasy Zone was never released due to a legal dispute with Sega over NEC's unauthorized use of the Fantasy Zone property.[109] However, bootleg copies were produced after a playable beta version of the game was released on the Internet.[97] Opa-Opa is included in Planet Harriers as a hidden character,[97] while one of three available endings in the 2007 PlayStation 2 release Fantasy Zone II DX has Harrier and Uriah attempting to eliminate a turned-evil Opa-Opa bent on destroying the game's eponymous Fantasy Zone.[110]

The arcade version of Space Harrier is included in the 1999 Dreamcast action-adventure title Shenmue as a minigame, and as a full port in the 2001 sequel Shenmue II. Sega Superstars Tennis and the 2010 action-adventure game Bayonetta feature Space Harrier-inspired minigames.[111][112] The title is available as an unlockable game in Sonic's Ultimate Genesis Collection (2009), for the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3, though with sound emulation differences.[87] In the 2012 title Sonic & All-Stars Racing Transformed, a remixed version of the Space Harrier main theme plays during the "Race of Ages" stage, in which a holographic statue of Harrier and a flying dragon appear in the background.[97] In addition, Shenmue character Ryo Hazuki pilots a flying Space Harrier sit-down arcade cabinet during airborne levels.[113] Sega included an emulation of the original title as a minigame in several titles of their Yakuza series, such as the 2015 release Yakuza 0,[114] and the 2018 releases Yakuza 6: The Song of Life, Fist of the North Star: Lost Paradise and Judgment.

Influenced games edit

The success of Space Harrier resulted in the development of other first/third-person rail shooters that attempted to emulate its three-dimensional scaling, visuals, and gameplay capabilities, causing them to be labeled "Space Harrier clones".[115] One of the most notable examples was the 1987 Square title The 3-D Battles of WorldRunner for the Famicom and Nintendo Entertainment System,[116][117][118] which was followed by Pony Canyon's 1987 Famicom release Attack Animal Gakuen[119] and other Japan-exclusive games such as Namco's Burning Force,[120] Asmik's Cosmic Epsilon,[121] and Wolf Team's Jimmu Denshō,[122] all released in 1989. According to AllGame, Nintendo's Star Fox (1993) "was influenced by early first-person 3D shooters such as" Space Harrier.[123]

According to The One magazine in 1991, Sega "arguably pioneered the deluxe ground-ride cabinet cum video game with classics such as" Space Harrier. Sega went on to produce "bigger" and "better" motion simulator cabinets for arcade flight games such as After Burner (1987) and the R360 cabinet for G-LOC: Air Battle (1990).[124]

Hideki Kamiya, the director of PlatinumGames and creator of the Devil May Cry series, cited Space Harrier as an inspiration for his entering the video game industry in a 2014 interview: "There were so many trend-setting definitive games that came out [in the 1980s], like Gradius and Space Harrier. All these game creators were trying to make original, really creative games that had never existed before".[125][126]

Game composer Yuzo Koshiro was a fan of the game's music. He said Space Harrier was the first time he had heard FM synthesis music, and the game inspired him to become a video game music composer. He considers Space Harrier composer Hiroshi Kawaguchi to be one of Sega's best ever composers.[127]

Series edit

- Space Harrier (1985) — Arcade, Master System, Game Gear, 32X, Sega Saturn, Dreamcast, various other non-Sega home systems

- Space Harrier 3-D (1988) — Master System

- Space Harrier II (1988) — Mega Drive/Genesis, Virtual Console, iOS, various other non-Sega systems

- Planet Harriers (2000) — Arcade only

- Space Harrier Sega Ages Edition (2003) — PlayStation 2

- Sega Ages 2500 Vol. 20: Space Harrier Complete Collection (2005) — PlayStation 2

- 3D Space Harrier (2013) — 3DS

See also edit

- Blaster, 1983 arcade game with similar gameplay

Notes edit

- ^ Often called "the Harrier" as a title instead of a proper name,[9][10] he is named "Harri" in several United Kingdom home releases of the game.[11][12]

- ^ This proper spelling appears in gameplay of the arcade and Master System versions and Space Harrier 3-D, but is written as "Euria" in the Master System instruction manual[14] and on both the packaging and manual for Space Harrier 3-D.[15][16] Both spellings appear in the latter game: "Dark Uriah" serves as the final boss, but "Euria" is seen in the game's ending text.

References edit

- ^ "Video Game Flyers: Space Harrier, Sega (EU)". The Arcade Flyer Archive. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Virtual Console: Space Harrier (Arcade version)". Sega. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ "Space Harrier (Registration Number PA0000282162)". United States Copyright Office. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Overseas Readers Column: Many Videos Unveiled But Visitors Decreased" (PDF). Game Machine. No. 270. Amusement Press, Inc. 1 November 1985. p. 26.

- ^ a b "セガハード大百科 MASTER SYSTEM/セガマーク3対応ソフトウェア" [Sega Hardware Encyclopedia MASTER SYSTEM/Sega Mark 3 software]. Sega (in Japanese). Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ "Sega Space Harrier Hardware". System16.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2006.

- ^ a b "Game Machine's Best Hit Games 25: '87" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 324. Amusement Press, Inc. 15 January 1988. p. 20.

- ^ a b Marriott, Scott Alan (14 November 2014). "Space Harrier - Overview". AllGame. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kalata, Kurt (December 8, 2013). "Hardcore Gaming 101: Space Harrier". hardcoregaming101.net. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Racketboy (Nick Reichert) (December 1, 2014). "Together Retro Game Club: Space Harrier". racketboy.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ^ "Space Harrier". dcshooters.co.uk. Archived from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Hill, Giles (February 18, 2014). "Vertical take-off and laughing: Space Harrier". The Register. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ a b "Space Harrier Stages". dcshooters.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 12, 2006. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Space Harrier Master System manual" (PDF). Sega Retro. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ a b "Space Harrier 3-D instruction manual" (PDF). Sega Retro. September 15, 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ "Space Harrier 3-D packaging". Sega Retro. July 4, 2013. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ a b "Space Harrier - Videogame by Sega". Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Mielke, James (December 8, 2010). "The Disappearance of Yu Suzuki: Part 2". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c Konstantin Govorun; et al. (November 2013). "Yu Suzuki interview". Strana Igr (Russian; translated and reprinted on ShenmueDojo.net). Gameland. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Nick Thorpe; Yu Suzuki (August 13, 2015). "The Making Of: Space Harrier". Retro Gamer. No. 145. Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing. pp. 22–31. ISSN 1742-3155.

- ^ a b Stanton, Rich (July 7, 2013). "Space Harrier retrospective". Eurogamer.net. Archived from the original on October 1, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ Lambie, Ryan (June 3, 2010). "The lost thrill of the cockpit arcade cabinet". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ^ Kent, Steven (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 501. ISBN 0761536434.

- ^ John D. Vince (ed.) (2003), Handbook of Computer Animation (p. 4-5), Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-1-4471-1106-1

- ^ a b Fahs, Travis (21 April 2009). "IGN Presents the History of SEGA". IGN. p. 3. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d Buchanan, Levi (5 September 2008). "Space Harrier Retrospective". IGN. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Sega Space Harrier Hardware (Sega)". System 16. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ^ Mielke, James (December 7, 2010). "The Disappearance of Yu Suzuki: Part 1". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ a b blackoak (2009). "The Rock Stars of Sega – 2009 Composer Interview". shmuplations.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b blackoak (2014). "Fantasy Zone – 2014 Developer Interview". Shmuplations.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c Edgeley, Clare (16 February 1986). "Arcade Action". Computer and Video Games. No. 53 (March 1986). Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ Horowitz, Ken (January 3, 2006). "History of: Space Harrier". Sega-16. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ^ a b Buchanan, Levi (2008-11-17). "Space Harrier Review". IGN. Archived from the original on 2016-06-25. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- ^ "Marc William Ericksen". Retrogaming Addict (in French). 10 February 2015. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ a b Taylor, Graham (December 1986). "Space Harrier". Sinclair User, p. 36-37. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Smith, Rachael (March 1987). "Space Harrier". Your Sinclair, p. 30. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Sega to bring classic titles to 3DS, starting with 3D Space Harrier". GamesRadar. 2012-11-21. Archived from the original on 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ^ Jenkins, David (December 23, 2013). "Sega 3D Classics review – from Streets Of Rage to Space Harrier". metro.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Sato (May 30, 2013). "3D Altered Beast Developers Talk About Adapting Genesis And Arcade Games For 3DS". Siliconera. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ a b Phillips, Joshua (November 26, 2013). "M2: Bringing Space Harrier To 3DS Was 'Almost Impossible', But It's 'The Definitive Version'". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ "3D Space Harrier Coming On December 26, Simulates Moving Arcade Cabinets". Siliconera. December 19, 2012. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Mackey, Bob (November 29, 2013). "Welcome to the Fantasy Zone: 3D Space Harrier Review". USGamer. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Diver, Mike (July 23, 2015). "The Classic Game 'Streets of Rage 2' Will Never Get Old". Vice.com. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "3D Space Harrier for 3DS Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- ^ "Sega Ages: Space Harrier for Switch Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- ^ a b Baker, Christopher Michael. "Space Harrier - Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Space Harrier - Review". AllGame. November 15, 2014. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Space Harrier - Overview". AllGame. 14 November 2014. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Space Harrier (Virtual Console)". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b "Finals". Next Generation. No. 2. Imagine Media. February 1995. p. 93.

- ^ Burkhill, Keith (December 1986). "Reviews: Space Harrier". Crash. World of Spectrum. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Lacey, Eugene. "Space Harrier Review (Amiga)" (PDF). Computer and Video Games (April 1989), p. 55. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Burkhill, Keith (January 1987). "Space Harrier: Welcome to the Fantasy Zone". Computer and Video Games. No. 63. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Computer and Video Games, Complete Guide to Consoles, volume 1, page 71

- ^ Rignall, Julian (16 March 1989). "Mean Machines: Space Harrier (PC Engine)". Computer and Video Games. No. 90 (April 1989). p. 108.

- ^ a b "ProReview: Space Harrier". GamePro. No. 69. IDG. April 1995. p. 58. Archived from the original on 2016-09-27. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- ^ Kalata, Kurt (April 8, 2008). "Classic Review Archive - Space Harrier". GameSpy. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Thomas, Lucas M. (November 3, 2008). "Space Harrier Review". IGN.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ "Space Harrier". Micromanía (in Spanish). No. 24. June 1987. p. 66.

- ^ Edgeley, Clare (18 January 1987). "The Arcade Coin-Op Giants for 1987". Sinclair User. No. 59 (February 1987). pp. 92–6.

- ^ "Banzai". Tilt (in French). No. 49. December 1987. pp. 106–7.

- ^ "Amiga: Space Harrier". Zzap!64. No. 48 (April 1989). 16 March 1989. pp. 22–3.

- ^ a b Roberts, Mike (March 1986). "Coin-Op Connection". Computer Gamer. No. 12. pp. 26–7.

- ^ a b "Best 10". Gamest (in Japanese). No. 2 (July 1986). 18 June 1986. p. 24.

- ^ "Space Harrier". The Arcade Flyer Archive. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ "Game Machine's Best Hit Games 25 - アップライト, コックピット型TVゲーム機 (Upright/Cockpit Videos)". Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 276. Amusement Press. 15 January 1986. p. 21.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 276. Amusement Press, Inc. 1 February 1986. p. 21.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 277. Amusement Press, Inc. 15 February 1986. p. 21.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 278. Amusement Press, Inc. 1 March 1986. p. 23.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 279. Amusement Press, Inc. 15 March 1986. p. 21.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 280. Amusement Press, Inc. 1 April 1986. p. 21.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 282. Amusement Press, Inc. 1 May 1986. p. 19.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 283. Amusement Press, Inc. 15 May 1986. p. 21.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 284. Amusement Press, Inc. 1 June 1986. p. 21.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 285. Amusement Press, Inc. 15 June 1986. p. 21.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 286. Amusement Press, Inc. 1 July 1986. p. 25.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 287. Amusement Press, Inc. 15 July 1986. p. 29.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 288. Amusement Press, Inc. 1 August 1986. p. 25.

- ^ "Best Hit Games 25" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 293. Amusement Press, Inc. 15 October 1986. p. 31.

- ^ "Game Machine's Best Hit Games 25: '86 上半期" [Game Machine's Best Hit Games 25: First Half '86] (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 288. Amusement Press, Inc. 15 July 1986. p. 28.

- ^ "Game Machine's Best Hit Games 25: '86 下半期" [Game Machine's Best Hit Games 25: Second Half '86] (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 300. Amusement Press, Inc. 15 January 1987. p. 16.

- ^ "The Charts". Your Computer. Vol. 7, no. 3. March 1987. p. 16.

- ^ Semrad, Edward (May 16, 1987). "'Harrier's' big memory has its good, bad sides". The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved September 30, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Worley, Joyce; Katz, Arnie; Kunkel, Bill (September 1988). "Video Gaming World". Computer Gaming World. pp. 50–51.

- ^ Campbell, Phil (May 15, 1989). "Dragon dodging delights". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Mellerick, Paul (March 1992). "Reviewed!: Space Harrier". Sega Force (p. 54). Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ a b Gerstmann, Jeff (February 16, 2009). "Sonic's Ultimate Genesis Collection Review". Giant Bomb. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ Rowe, Brian (September 27, 2011). "Rail Shooters Every Fan Should Own". Gamezone. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Brown, Tom (December 20, 2015). "Sega Sunday: Space Harrier". Nintendo Wire. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Wilson, Trevor (June 28, 2006). "COLUMN: 'Compilation Catalog' - Sega Ages 2500: Space Harrier II". GameSetWatch. Archived from the original on July 14, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Darran (July 16, 2008). "Space Harrier". Retro Gamer. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ Twice, Eric (May 24, 2013). "Flashback: Space Harrier's a model of Suzuki precision". Snackbar Games. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Francisco, Eric (July 15, 2015). "RETRO GAME REPLAY 'Space Harrier' (1985)". Inverse.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Towell, Justin; Sullivan, Lucas (March 31, 2014). "The 25 best bonus levels of all time". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Vas, Gergo (February 4, 2013). "The Trippiest Video Game Levels". Kotaku. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Welch, Hanuman (November 10, 2013). "10 Sega Games Desperate for a Modern Reboot". Complex.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kalata, Kurt (December 8, 2013). "Hardcore Gaming 101: Space Harrier (page 2)". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ Alaimo, Chris (May 14, 2014). "Space Harrier II". Classic Gaming Quarterly. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (September 5, 2008). "Space Harrier Retrospective (page 3)". IGN. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ a b "3D Space Harrier Interview with Developer M2". blogs.sega.com. November 25, 2013. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ Gerstmann, Jeff (April 1, 2005). "Sega Classics Collection Review". Giant Bomb. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- ^ "SEGA AGES 2500シリーズ Vol.20" [SEGA AGES 2500 SERIES Vol.20]. Sega (in Japanese). 2005. Archived from the original on August 3, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ "SEGA AGES 2500シリーズ Vol.20 スペースハリアーII 〜スペースハリアーコンプリートコレクション〜" [SEGA AGES 2500 Series Vol.20 Space Harrier II ~ Space Harrier Complete Collection]. Playstation.com (in Japanese). 2005. Archived from the original on February 16, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ^ Renaudin, Josiah (October 25, 2013). "Sega Will Remake the Classics Fans Want to See". Gameranx. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Staff (November 2, 2005). "Now Playing in Japan". IGN. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ "Sega Ages 2500 Vol.20: Space Harrier II". Sega Ages (in Japanese). Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ Fahs, Travis (October 1, 2008). "Fantasy Zone Retrospective". IGN. Archived from the original on September 24, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ "Space Fantasy Zone". Sega Retro. Archived from the original on September 24, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ Reis, Marcelo. "Space Fantasy Zone". Universo PC Engine. Archived from the original on September 24, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ Kalata, Kurt (July 15, 2014). "Hardcore Gaming 101: Fantasy Zone". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ Geddes, Ryan (March 19, 2008). "Sega Superstars Tennis Review". IGN.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Hoggins, Tom (October 20, 2014). "Bayonetta 2 review". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ Powell, Chris (December 30, 2013). "SEGA confirms Ryo Hazuki in Sonic & All-Stars Racing Transformed". Sega Nerds. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ Van Allen, Eric (January 19, 2017). "Yakuza 0 Is an Almost Flawless Mix of Action, Comedy, and History". Paste. Wolfgang's Vault. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ Lim Choon Wee; et al. (October 25, 1990). "New Releases". New Straits Times. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Tryie, Ben (February 28, 2011). "The 3-D Battles of World Runner". Retro Gamer. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- ^ Gesualdi, Vito (February 22, 2013). "Five most notorious videogame ripoffs of all time". Destructoid. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Charlton, Chris (November 30, 2015). "This Month in Gaming History: December 1985-2015". KaijuPop.com. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Kalata, Kurt; Derboo, Sam (September 5, 2014). "1980s Video Game Heroines". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ Kalata, Kurt (May 21, 2013). "Burning Force". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ Cifaldi, Frank (January 11, 2010). "Flyers and handouts from Winter CES 1990". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Gifford, Kevin (May 24, 2010). "[I ♥ The PC Engine] Jimmu Denshō". magweasel.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ Weiss, Brett Alan (6 December 2014). "Star Fox - Overview". AllGame. Archived from the original on 2014-12-06. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ Nesbitt, Brian (28 January 1991). "Coin-Operated Corkers!". The One. No. 29 (February 1991). EMAP Images. p. 20.

- ^ Leone, Matt (May 28, 2009). "Hideki Kamiya Profile". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Lawson, Caleb (September 15, 2014). "IGN Presents: Inside Devil May Cry Creator Hideki Kamiya's Secret Arcade". IGN. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Yuzo Koshiro". Red Bull Music Academy. Red Bull GmbH. 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

External links edit

- Space Harrier at Coinop.org

- Space Harrier at MobyGames

- Space Harrier at SpectrumComputing.co.uk

- Space Harrier at arcade-history

- Space Harrier for Virtual Console (in Japanese)