Summary

The spotback skate (Atlantoraja castelnaui) is a species of fish in the family Arhynchobatidae. It is found off the Atlantic coasts of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay where its natural habitat is over the continental shelf in the open sea. It is a large fish, growing to over a metre in length. It feeds mainly on other fish according to availability, with shrimps, octopuses and other invertebrates also being eaten. Reproduction takes place throughout most of the year, with the eggs being laid in capsules that adhere to the seabed. The spotback skate is the subject of a fishery and is thought to be overfished, resulting in Greenpeace adding the fish to its red list of fish to be avoided, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature listing it as an "endangered species".

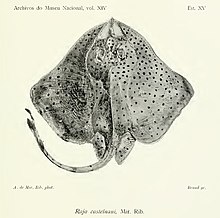

| Spotback skate | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Superorder: | Batoidea |

| Order: | Rajiformes |

| Family: | Arhynchobatidae |

| Genus: | Atlantoraja |

| Species: | A. castelnaui

|

| Binomial name | |

| Atlantoraja castelnaui (A. Miranda-Ribeiro, 1907)

| |

Distribution edit

The Atlantoraja castelnaui are found in the Southwest South Atlantic Ocean from Rio de Janeiro State in Brazil to Argentina. They prefer warm-temperate waters at depths ranging from 20 to 220 m.[2] In Argentina, they can be found as natives to the Argentinian Zoogeographic Province. They seek warm water climates, and are often reported to have a more southern distribution than normal in correlation with higher water temperatures. Spotback skates may migrate only slightly or perform slight periodic backwards and forwards movement depending on ocean water temperatures.[3] However, there is no notable seasonal variation for the species as they populate southern waters year round.

Although the location of their distribution has not been affected, the quantity of the spotback's distribution has lowered in many places and continues to be threatened by humans fishing in its habitats.[2]

Reproduction edit

The length of maturity for males and females differ with males ranging from 185 to 1250 mm in total length and females ranging from 243 to 1368 mm in total length.[4] Males have a continuous production of mature spermatozoa suggests they can reproduce throughout the year but studies have shown higher values in certain months but they are not significant. Females also reproduce year-round with peaks of reproductive activity as well.[4]

Female spotback skates lay their eggs on the ocean floor and leave them there. There is not parental care so the eggs have a capsule that protects the embryo's development once the mother leaves.[5] Collected egg capsules typically are rectangular and have horny process in each corner. They are also shiny and are medium brown in color.[5] The capsules on the eggs are covered by adhesion fibrils that allow the egg to attach itself to the sea floor immediately after the mother releases them. These adhesion fibrils are also seen in other species of skates.[5] The surface of the capsule is striated and presents a rough surface though it is relatively smooth. Atlantoraja castelnaui capsule's are also the largest egg capsule in its genus and compared to other co-occurring species in the same area and depth of the ocean.[5]

Conservation status edit

In the cities of Santos and Guarujá, specimens of the spotback skate which are deemed large enough to have commercial value are commonly landed and marketed.[4] From 1999 to present, the market for the meat of the spotback skate has expanded to Asia, particularly South Korea.[4] As a result, commercial fishing has led to an overexploitation of the species and its consequent listing as an endangered species.

Spotback skates are particularly vulnerable to extinction[6] due to their large body size relative to other skate species. According to Dulvy & Reynolds (2002), skate species considered to be locally extinct have larger body sizes compared to all other skates.[4] Large body size is in turn correlated with higher mortality rates and with life-history parameters such as late age at maturity.[4] Another study by García et al. (2007) also corroborated the notion that a large body size increased the extinction risk in elasmobranchs.[4] Spotback skates are also especially vulnerable to trawl fisheries because they inhabit the soft bottom substrates of the ocean (Ebert; Sulikowski, 2007).[7] Consequently, the biomass of spotback skates has decreased by 75% from 1994 to 1999.[1][7]

Behavior and eating habits edit

The spotback skate is found across most of the continental shelf year round.[6] The spotback skate's diet is a versatile and mainly piscivorous consumer. Their diet shifts with increasing body size and as a response to seasonal and regional changes in prey abundance and distribution. They prey mostly on teleost, cephalopods, elasmobranchs, and decapods. Smaller spotback skate tend to consume decapods and the larger skates ate elasmobranchs and cephalopods.[8] The consumption of teleosts differed between seasons depending on whether the teleost were demersal- benthic or benthic. The more demersal- benthic teleosts were consumed during the cold season while the benthic teleosts were eaten during the warm season.[8] The decapods, cephalopods and elasmobranchs were predominantly shrimps, octopuses, and skates. The main cephalopod consumed in the warm season was the octopus.[7]

Parasites edit

Like all fish species, spotback skates have a variety of parasites; these include copepods,[9] nematodes[10] and Myxozoans.[11]

Sustainable consumption edit

In 2010, Greenpeace International has added the spotback skate to its seafood red list. "The Greenpeace International seafood red list is a list of fish that are commonly sold in supermarkets around the world, and which have a very high risk of being sourced from unsustainable fisheries."[12]

References edit

- ^ a b Pollom, R.; Barreto, R.; Charvet, P.; Chiaramonte, G.E.; Cuevas, J.M.; Faria, V.; Herman, K.; Motta, F.; Paesch, L.; Rincon, G. (2020). "Atlantoraja castelnaui". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T44575A152015479. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T44575A152015479.en. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b Oddone, Maria Cristine (28 October 2015). "Length-weight relationships, condition and population structure of the genus Atlantoraja (Elasmobranchii, Rajidae, Arhynchobatinae) in Southeastern Brazilian waters, SW Atlantic Ocean" (PDF). Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science. 38: 43–52. doi:10.2960/J.v38.m599. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Bovcon, N. D.; Cochia, P. D.; Góngora, M. E.; Gosztonyi, A. E. (2011). "New records of warm-temperate water fishes in central Patagonian coastal waters (Southwestern South Atlantic Ocean)". Journal of Applied Ichthyology. 27 (3): 832–839. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0426.2010.01594.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g Oddone, María C.; Amorim, Alberto F.; Mancini, Patricia L. (2008). "Reproductive biology of the spotback skate, Atlantoraja castelnaui (Ribeiro, 1907) (Chondrichthyes, Rajidae), in southeastern Brazilian waters" (PDF). Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía. 43 (2): 327–334. doi:10.4067/S0718-19572008000200010.

- ^ a b c d Oddone, Maria C. (2008). "Description of the egg capsule of Atlantoraja castelnaui (Elasmobranchii, Rajidae)". Brazilian Journal of Oceanography. 56 (1): 65–68. doi:10.1590/S1679-87592008000100007. hdl:11449/26939.

- ^ a b Barbini, Santiago A.; Lucifora, Luis O. (2012). "Feeding habits of a large endangered skate from the south-west Atlantic: the spotback skate, Atlantoraja castelnaui". Marine and Freshwater Research. 63 (2): 180–188. doi:10.1071/MF11170.

- ^ a b c Orlando, Luis; Pereyra, Ines; Paesch, Laura; Norbis, Walter (December 2011). "Size and sex composition of two species of the genus Atlantoraja (Elasmobranchii, Rajidae) caught by the bottom trawl fisheries operating on the Uruguayan continental shelf (southwestern Atlantic Ocean)". Brazilian Journal of Oceanography. 59 (4): 357–364. doi:10.1590/S1679-87592011000400006.

- ^ a b Barbini, S. A.; Scenna, L. B.; Figueroa, D. E.; Díaz de Astarloa, J. M. (1 July 2013). "Effects of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on the diet of Bathyraja macloviana, a benthophagous skate". Journal of Fish Biology. 83 (1): 156–169. doi:10.1111/jfb.12159. ISSN 1095-8649. PMID 23808698.

- ^ Irigoitia, Manuel M.; Cantatore, Delfina M.P.; Incorvaia, Inés S.; Timi, Juan T. (2016). "Parasitic copepods infesting the olfactory sacs of skates from the southwestern Atlantic with the description of a new species of Kroeyerina Wilson, 1932". Zootaxa. 4174 (1): 137–152. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4174.1.10. ISSN 1175-5334. PMID 27811793.

- ^ Irigoitia, Manuel Marcial; Braicovich, Paola Elizabeth; Lanfranchi, Ana Laura; Farber, Marisa Diana; Timi, Juan Tomás (2018). "Distribution of anisakid nematodes parasitizing rajiform skates under commercial exploitation in the Southwestern Atlantic". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 267: 20–28. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.12.009. ISSN 0168-1605. PMID 29277002.

- ^ Cantatore, Delfina María Paula; Irigoitia, Manuel Marcial; Holzer, Astrid Sibylle; Bartošová-Sojková, Pavla; Pecková, Hana; Fiala, Ivan; Timi, Juan Tomás (2018). "The description of two new species of Chloromyxum from skates in the Argentine Sea reveals that a limited geographic host distribution causes phylogenetic lineage separation of myxozoans in Chondrichthyes". Parasite. 25: 47. doi:10.1051/parasite/2018051. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 6134877. PMID 30207267.

- ^ Greenpeace International Seafood Red list