Summary

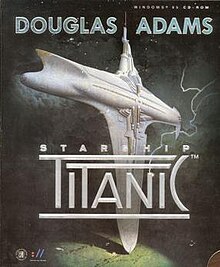

Starship Titanic is an adventure game developed by The Digital Village and published by Simon & Schuster Interactive. It was released in April 1998 for Microsoft Windows and in March 1999 for Apple Macintosh. The game takes place on the eponymous starship, which the player is tasked with repairing by locating the missing parts of its control system. The gameplay involves solving puzzles and speaking with the bots inside the ship. The game features a text parser similar to those of text adventure games with which the player can talk with characters.

| Starship Titanic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | the Digital Village |

| Publisher(s) | Simon & Schuster Interactive |

| Producer(s) |

|

| Designer(s) | Douglas Adams Adam Shaikh Emma Westecott |

| Writer(s) | Douglas Adams Michael Bywater Neil Richards |

| Composer(s) | Wix Wickens Douglas Adams |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Written and designed by The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy creator Douglas Adams, Starship Titanic began development in 1996 and took two years to develop. In order to achieve Adams's goal of being able to converse with characters in the game, his company developed a language processor to interpret player's input and give an appropriate response and recorded over 16 hours of character dialogue. Oscar Chichoni and Isabel Molina, artists on the film Restoration (1995), served as the game's production designers and designed the ship's Art Deco visuals. The game's voice cast includes Monty Python members Terry Jones and John Cleese. A tie-in novel titled Douglas Adams's Starship Titanic: A Novel was written by Jones and released in October 1997.

Starship Titanic was released to mixed reviews and was a financial disappointment, although it was nominated for three industry awards and won a Codie award in 1999. It was re-released for modern PCs in September 2015 by GOG.com.

Gameplay edit

Starship Titanic is a graphic adventure game played from a first-person perspective. The player moves on the eponymous ship by clicking on locations indicated by the cursor and advancing to the next frame after a blurred transition (although this can be avoided by holding down shift during clicks).[1] The mouse can also be used to pick up and store items in your inventory and interact with onscreen objects.[2] In the beginning of the game, the player is given a device called Personal Electronic Thing (PET), which serves as a toolbar on the bottom of the screen. The PET has five modes: Chat-O-Mat, a text parser through which the player can talk with characters by inputting text; Personal Baggage, the inventory in which the player can add or withdraw items; Remote Thingummy, a set of functions to interact with objects and locations; Designer Room Numbers, which indicates the player's current location; and Real Life, an options menu with settings and a game save/load system.[3]

Much of the gameplay involves solving puzzles by using items with other items or with objects and characters onscreen.[4] Another significant aspect of the game involves talking with characters in the game, namely the bots that work in the ship and a parrot, by inputting prompts in the Chat-O-Mat mode. Additionally to conversation with characters through interpreting of user input, the parser often provides hints or explanations that come in the form of pre-recorded speech, which can help the player in progressing in the game.[5]

The main objective of the game is to locate the missing parts of the ship's broken intelligence system in order to repair the starship. In order to advance within the game, the player must upgrade from the standard third class level to first class and thus gain access to areas that are restricted when the game begins.[6][7] The game also requires the player to transport items throughout the ship through the Succ-U-Bus, a system of tubes that transfer objects placed in them to other parts of the ship; these tubes can be found in many areas of the ship.[4][7] The player also needs to use the parrot to solve certain puzzles.[8] A talking bomb can be found in the game and unwillingly armed by the player; if that happens, the player has to either disarm it or distract it during countdown to prevent it from exploding.[9][10]

Plot edit

Starship Titanic begins in the player character's house on Earth, which is partially destroyed when the eponymous cruise ship crash-lands through the roof. Fentible, the "DoorBot", informs the player that the ship and its crew have malfunctioned and needs help to get them back to normal. Once the ship is taken back to space, the player meets Marsinta, the "DeskBot", who makes them a third-class reservation, and Krage, a "BellBot". The player begins the journey as a third-class passenger and thus cannot access many areas of the ship that are reserved for higher class passengers until he or she obtains a second-class promotion and eventually convinces Marsinta to upgrade them to first class after managing to alter her personality.

Through backstory in the ship's email system, the player learns that Brobostigon and Scraliontis, two associates of the ship's creator Leovinus, double crossed him and deliberately provoked a "Spontaneous Massive Existence Failure" by hiding the body parts of the ship's humanoid intelligence system Titania in various locations within the ship as well as planting a scuttling bomb, in an effort to destroy the ship and profit from its insurance. However, both men perished in the attempt with the player finding their dead bodies on the ship. After exploring the vessel and solving puzzles, the player eventually finds all of Titania's body parts and awakens her, repairing the sabotaged ship and allowing for it to be navigated. The player then accesses the bridge and navigates the ship back to their home on Earth. Throughout the game, the player meets other bots, including Nobby, the "LiftBot", Fortillian, the "BarBot" and D'Astragaaar, the "Maitre d'Bot". The player also meets a parrot that accompanies them throughout most of the journey.

After returning to Earth, the player gets a message from Leovinus (played by Douglas Adams) who announces that he has decided to retire on Earth as a fisherman and to find a wife. Depending on if the bomb was disarmed, one of two endings occurs:

- If the bomb wasn't disarmed, the ship takes off and explodes in midair.

- If the bomb was disarmed, the ship simply takes off and the player is informed by Leovinus that, by galactic salvage laws, they now own the Starship Titanic.

Development edit

Background edit

Douglas Adams first imagined the Starship Titanic in Life, the Universe and Everything, the third entry in The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series, where it is briefly mentioned in the book's 10th chapter. Adams describes the ship—named after the famous ocean liner—as a "majestic and luxurious cruise-liner" that "did not even manage to complete its very first radio message—an SOS—before undergoing a sudden and gratuitous total existence failure".[11][12]

Before making Starship Titanic, Adams had previously served as a designer for Infocom's 1984 text-based game The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, which was based on his successful science fiction series of the same name,[13][14] and had been an advocate for "new media".[15] Since working with Infocom, Adams had expressed interest in returning to game design, and feared that he was spending too much time by himself writing.[16][17] He turned to game design again after playing Myst, which is when he said "the medium had gotten interesting again".[16] However, he thought Myst was lacking in story and characters.[18] Commenting on the gameplay of Myst and its sequel Riven, Adams said that "nothing really happens, and nobody is there. I thought, let's do something similar but populate the environment with characters you can interact with",[17] and hoped to combine graphics and a text-based system that allowed for players to converse with characters in the game.[19]

In 1996 Adams co-founded The Digital Village, a company intended to handle his future endeavours in film, print and new media.[20] Adams first discussed founding the company with Robbie Stamp, a producer at Central Independent Television in the early 1990s, and they did so along with Stamp's boss at Central, Richard Creasey; literary agent Ed Victor was also one of the company's founders. Ian Charles Stewart, one of the founders of Wired, joined the enterprise shortly thereafter.[21] In December 1995, The Digital Village arranged a deal to raise seed capital from venture capitalist Alex Catto, who bought 10% of the company's shares for £400,000.[22] In 1996 Simon & Schuster Interactive reached a deal with the company to finance Starship Titanic, whose budget was estimated at $2 million.[23]

Development of the game began Summer 1996.[24] Around 40 people worked on the game's development.[16]

Writing edit

The story was created by Adams, who wrote the game's script with Michael Bywater[16] and Neil Richards.[25][26] Additional dialogue was written by D. A. Barham.[26] Adams's inspiration for the game—particularly the objective of upgrading from third to first-class—came from an experience with airline ticketing personnel, where he was told he would be given an upgrade from economy-class tickets upon checking in for his flight, but found out upon arrival that the upgrade had not been arranged; he said the idea is based on the premise that "everyone wants a free upgrade in life".[15][27] Adams had devised a story concept to add an additional gameplay element where players would be able to enter the ship's data system as a "full realtime, flyable environment" and control how information flows through the vessel, but the idea was abandoned because, according to Adams, it was "a bridge too far".[28]

Adams aimed to develop a text parser-based dialogue system as opposed to the drop-down conversation menus of contemporary adventure games, in which player have limited dialogue options.[28][29] The text parser includes over 30,000 words and 16 hours of dialogue recorded by voice actors.[17] According to Adams, over 10,000 lines of dialogue were recorded for the game.[16] In order to make conversations with characters convincing, The Digital Village's Jason Williams and Richard Millican created a language processor called SpookiTalk, which was based on VelociText, a software developed by Linda Watson of Virtus Corporation.[26][30] Producer Emma Westecott thought the processor was preferable as common text-to-speech programs "made the voices sound cold and distant". Douglas Adams claimed that they made "all of your characters sound like semi-concussed Norwegians".[31] The bots in the game understood around 500 words of vocabulary and were capable of conversing with the player as well as each other. According to Westecott, the developers' intention was "getting into characters" and cited games such as Myst and Mortal Kombat as contemporary games that lacked "proper interaction" with human characters.[32] Williams and Millican modified VelociText into SpookiTalk in order to improve recognition of complicated sentence forms from players, as well as reducing repeated responses, and retaining a character's memory of an object or topic as a conversation progresses.[30][33][34] Additional dialogue support was done by linguist Renata Henkes.[35][26]

Design edit

The futuristic, Art Deco visuals were designed by Oscar Chichoni and Isabel Molina, who also worked on the 1995 Oscar-winning film Restoration.[36][37] Chichoni drew the initial sketches of the ship on a flight to Los Angeles on the day he and Molina joined the project.[38] Adams described the ship's interior design as a mixture of the Ritz Hotel, the Chrysler Building, Tutankhamun's tomb and Venice.[17] In order to make the design of the ship similar to Art Deco, Molina and Chichoni drew inspiration from 1950s American electrical appliances and modern architecture; to design the ship's external shape, they also drew from bones and dinosaur skeletons.[39]

Adams, Chichoni and Molina gave detailed briefings for the animators for each environment and character in the game.[40] Modeling and animation for the 30 environments and 10 characters was done on Softimage 3D, version 3.5. Most environments were done separately. However, the center of the ship in particular also included other environments as it connects the first and second class canals, the top of the well and the central well; Darren Blencowe was responsible for modeling the ship's center.[41] A total of six 3D artists worked on the game.[32] Rendering was done on Mental Ray; in order to complete the rendering in time, the team's systems administrator wrote a Perl-based software to control all rendering jobs for up to 20 processors working 24 hours a day.[38] In order to animate the parrot, Philip Dubree, one of the team's animators, visited pet shops and studied macaws for inspiration. Dubree created a skeleton and modeled the wings and feathers, later adjoining the body. He also scanned photos of macaw features and used Photoshop to incorporate those in the parrot's textures.[41] In order to create Titania's statue at the Top of the Well, animator John Attard built the 3D model as a refractive metallic structure and texturized it with streaks of oxidation on her face; Attard used the Statue of Liberty as a visual reference.[40]

Programming was done on The Digital Village's own developed engine, Lifeboat.[32] The engine was developed by programmers Sean Solle and Rik Heywood, who joined the company in January 1997.[42] Their intention when developing Lifeboat was allowing simultaneous work on different parts of the game, facilitating game test runs and unifying the work of coders and 3D animators. The engine went live on 14 February 1997. To keep within a data budget of 1.8 gigabytes, the team used the MP3 sound format to compress the 16 hours of speech and dialogue, and compressed movies and cutscenes with Indeo. The final set of the game CDs were burned 400 days after the first build of Lifeboat.[35]

Sound edit

Sound designer John Whitehall, who was in charge of the company's sound studio during the recording process, worked with Adams on creating the sound for the game. Whitehall and Adams had previously collaborated in the radio version of Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy for the BBC, where Whitehall was a studio manager. The voice cast included actors Laurel Lefkow, Quint Boa, Dermot Crowley and Jonathan Kydd, who voiced the bot characters in the game.[43] Monty Python members Terry Jones and John Cleese also lent their voices to characters in the game. Jones, a longtime friend of Adams, provided the voice of the parrot,[44] while Cleese (who is credited as "Kim Bread")[26] voiced the bomb.[45] Actor Philip Pope was also involved, having voiced the Mâitre d'Bot.[43] Adams himself also did voice acting for the game,[11] voicing the Succ-U-Bus[28] and Leovinus.[26]

The ambient music for the game was composed by Paul Wickens, who is also a member of Paul McCartney's touring band.[17] Adams and Wickens were acquainted from school, but lost touch until Adams saw him performing with McCartney.[43] Adams also wrote additional soundtrack himself, including the music in the Music Room puzzle, which was based on a tune he had written on the guitar years earlier.[46]

Novel edit

A 1997 novelisation was written by Terry Jones as part of his involvement with the game development, the spinoff planned alongside the game. An audiobook version was also released, followed by an e-book version ten years later, and a radio dramatisation over twenty years later.

Release edit

In May 1996, Simon & Schuster Interactive announced a deal to co-publish Starship Titanic with The Digital Village.[47] Simon & Schuster presented the game along with 11 other projects at E3 1997.[48] Release was originally slated for September 1997,[24] but was postponed for December 1997 in time for the U.S. Christmas season.[49] However, the game was delayed again, and in January 1998 Adams said the game "should be ready by March".[18]

The game was eventually released on 2 April 1998 for PC,[50][51] and had an official launch at a New York City event, at 550 Madison Avenue, on 20 April 1998.[52][29] Simon & Schuster made an initial April distribution of 200,000 copies to be shipped to 13 countries through seven international publishers.[53][54] Zablac Entertainment secured the publishing rights in the United Kingdom, while NBG EDV Handels & Verlags AG acquired the rights in German, R&P Electronic Media did so in the Netherlands and Benelux territories, and HILAD in Australia and New Zealand.[55] Apple, Inc. announced on 8 July 1998 that Starship Titanic, along with many other games, would be released for Macintosh computers in the future.[56] The game was released for the Mac on 15 March 1999.[57][58] Sonopress developed a DVD version of the game, which was released in the UK in May 1999.[59][60]

Sales for the game were financially disappointing. [51] Simon & Schuster marketing VP Walter Walker estimated that the game had sold over 60,000 copies by the end of April, far below the expected number of 200,000.[61] In the United States, it sold 41,524 copies and earned $1,841,429 by July;[62] sales in that country rose to 150,000 copies by August 1999.[63] According to the company's creative director Jeff Siegel, a DVD version of the game "did not really sell" despite being an alternative to the three-CD original release.[64] According to Douglas Adams biographer Nick Webb, The Digital Village CEO Robbie Stamp sold the rights of Starship Titanic and all associated intellectual property to Thomas Hoegh's Arts Alliance in September 1998.[65]

The game's Windows version was re-released for modern PCs on digital download by GOG.com on 17 September 2015.[66][67]

Reception edit

| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| GameRankings | 63.79%[68] (score based on 19 reviews) |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Adventure Gamers | |

| Computer Gaming World | |

| GameSpot | 7.1/10 |

| IGN | 4.9/10 |

| Next Generation | [5] |

| PC Gamer (US) | 64% |

| PC PowerPlay | 71% |

| PC Zone | 91% |

| Computer Games Strategy Plus | |

| Adventure Classic Gaming | |

| PC Games | B+ [69] |

| MacAddict | "Freakin' Awesome!"[70] |

Starship Titanic received generally mixed reviews. Review aggregator GameRankings gives the game a score of 63.79% based on 19 reviews in the website.[68] Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World gave the game two and a half stars out of five, praising the graphics and visuals as "gorgeous", but criticizing the playability, the bots' responses in the text parser, and ultimately thought that the game is "just not very funny".[71] Adventure Gamers's Evan Dickens similarly praised the graphics and "beautiful" animation, but criticized the navigation and the parser, writing that the bots "won't understand or respond correctly to a single thing [the player asks]", and called it an "antiquated keyword-recognition system". He also described the puzzles as "contrived and unnecessary".[72] IGN reviewer Chris Buckman gave the game a 4.9/10 score, criticizing the lack of a backstory, the movement sequences and navigation, and the obscurity of the puzzles.[73]

Writing for PC Gamer US, Stephen Poole called Starship Titanic "an uninspiring and ultimately tedious adventure." He criticized the parser as unhelpful and thought there are few characters to interact with, although he praised the puzzles as "involved and challenging" and compared them to those of classic adventure games.[74] David Wildgoose of PC Powerplay gave the game a 71% rating, writing that the parser is "a refreshing change to the predictable keyword or menu conversation systems" of most contemporary games, and praised the difficulty of the puzzles. However, Wildgoose thought the game was "a bit of a disappointment", believing that it should have been longer and expected it to be funnier.[75] In a review for Computer Games Strategy Plus, Cindy Yans gave the game three and a half stars out of five. She also criticized the parser for failing to understand context in conversations, and called the navigation and item usage "cumbersome"; however, she praised Adams's humor, the animations and graphics.[76] CNN's Brad Morris praised the game overall, but compared its graphics unfavorably to contemporary games such as Riven and Zork Nemesis, and said that "it is not a revolution in this genre".[77] Stuart Clarke of The Sydney Morning Herald praised the graphics and the game overall, but said players will "do much scratching of the head and aimless wandering in circles before the mysteries of the Titanic are solved".[7] GameSpot's Ron Dulin gave the game a 7.1 score, criticizing the lack of a story but praising the humor, graphics and the presence of a text parser as "a nice nod to the days of old".[78]

Next Generation praised the text parser and wrote that as the game progresses, "it's impossible to get anywhere" without asking the bots questions, adding that "the humor of the answers alone makes it worth asking questions".[5] Paul Presley of PC Zone gave the game a score of 91%, praising its atmosphere as "totally absorbing" and commended it for its humor and presentation as well.[79] Alex Cruickshank of PC Magazine called it a "pleasantly entertaining adventure" and praised the graphics, gameplay and puzzles.[45] Reviewing the Mac version, Mike Dixon of MacAddict gave it a positive review, praising the graphics, the recorded dialogue and the humor, whilst giving minor criticism to the interface.[6] Entertainment Weekly's Megan Harlan gave the game an A, praising the parser and the ability to converse with the bots, as well as their responses.[37] In a Computer Shopper review, Jim Freund wrote the game "provides many hours of enjoyable game play" and suggested that it might be "a milestone in the annals of interactive fiction".[80] Writing for USA Today, Jeffrey Adam Young rated it three and a half stars out of four, calling it a "hilarious blend of Monty Pythonesque humor and zany wordplay in a sci-fi setting" and praising it for its characters and script.[81] New York Daily News reviewer Kenneth Li gave the game three and a half stars out of four, calling it "breathtaking" and praising the storyline; however, he offered minor criticism towards repetitive replies in the text parser.[82] Joe Brussel of Adventure Classic Gaming rated the game four stars out of five, writing that the puzzles are "entertaining but not too hard" and praised the voice acting and graphics, although he wrote the story is "a little shortsighted".[83]

The game received two nominations for the BAFTA Interactive Awards in the categories of Comedy and Interactive Treatment in October 1998,[84] and was nominated for PC Adventure Game of the Year at the 2nd Annual Interactive Achievement Awards.[85] Likewise, the editors of The Electric Playground nominated Starship Titanic for their 1998 "Best Adventure Game" award, which ultimately went to Grim Fandango.[86] However, it was given a Codie award in 1999 for "Best New Adventure/Role Playing Game" by the Software and Information Industry Association.[87]

Legacy edit

In a 2015 article, Kotaku contributor Lewis Packwood wrote that "perhaps the Starship Titanic's most enduring legacy" is a forum in the older version of the game's official website, which was developed by The Digital Village's web developer Yoz Grahame. The starship's fictional construction company Star-Struct Inc., "a wholly-owned subsidiary" of the fictional travel agency Starlight Lines Corp., contained an "employee forum" that became popular months after it was created, entirely through user-generated content. Users role-played as fictional employees and characters in the ship, and created scenarios, storylines and in-jokes that developed over years. After The Digital Village closed, Grahame hosted the website himself and kept the domain alive.[88]

Shortly after Starship Titanic, The Digital Village (which was renamed to h2g2) developed an online guide based on Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy called h2g2, which became a BBC domain after the company shut down in 2001.[89][90][91] In 2011, the BBC sold h2g2 to Not Panicking Ltd.[92]

References edit

Citations edit

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 44.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 45.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 19-23.

- ^ a b Kalata, Kurt (13 July 2010). "Hardcore Gaming 101: Starship Titanic". Hardcoregaming101.net. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ a b c "Starship Titanic". Next Generation. 4 (43): 110–111. July 1998.

- ^ a b Dixon, Mike (July 1999). "Starship Titanic". MacAddict. 4 (7): 72.

- ^ a b c Clarke, Stuart (25 April 1998). "Polly's found a cracker". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 41. p. 7.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 76.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 58.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 74.

- ^ a b Packwood, Lewis (27 January 2015). "The Secret Douglas Adams RPG People Have Been Playing for 15 Years". Kotaku. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (2005). "10". Life, the Universe and Everything. Del Rey Books. pp. 92–93. ISBN 0-345-39182-9.

- ^ Lynch, Dennis (30 April 1998). "'Hitchhiker' Douglas Adams Back in Space". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Infocom's Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy playable for free online". Engadget. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Network: The Starship Titanic? Its only mission is to make you think". The Independent. 18 November 1997. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Harper, Charlotte (25 April 1998). "The intergalactic Adams family". Icon. No. 41. The Sydney Morning Herald. pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d e Stone, Brad (13 April 1998). "The unsinkable starship". Newsweek. Vol. 131, no. 15. pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Sherry, Kevin F. (18 January 1998). "Busy writer gets Pythons to help". Los Angeles Daily News. p. V5.

- ^ Covert, Colin (24 April 1998). "Hitchhiker' takes another galactic trip; Science-fiction author Douglas Adams, in town today, has created an interactive CD-ROM". Star Tribune. p. 23E.

- ^ Daoust, Phil (15 January 1998). "Take me to your viewer". G2. The Guardian. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Webb 2005, p. 290.

- ^ Webb 2005, p. 291.

- ^ Webb 2005, p. 293.

- ^ a b Webb 2005, p. 298.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Starship Titanic final credits

- ^ "Games Evolve From Shoot-'Em-Ups; Computer and Media Giants Zap Away Over the $17 Billion Industry". International Herald Tribune. 16 February 1998. p. 11.

- ^ a b c "Interview with Douglas Adams". Edge. No. 57. April 1998. pp. 24–26.

- ^ a b Kushner, David (16 April 1998). "Starship Titanic Sails into Computer Gaming". Wired. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ a b Richards 1998, p. 71.

- ^ Phipps, Keith. "Douglas Adams". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Faber, Liz (December 1997). "Starship enterprise". Creative Review. Vol. 17. pp. 46–47.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 72.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 73.

- ^ a b Richards 1998, p. 101.

- ^ Glaser, Mark (4 May 1998). "A Flight to Remember". Los Angeles Times. pp. F1, F13.

- ^ a b Harlan, Megan (8 May 1998). "Starship Titanic". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ a b Richards 1998, p. 61.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 77.

- ^ a b Richards 1998, p. 60.

- ^ a b Coco, Donna (October 1997). "Starship Titanic". Computer Graphics World. Vol. 20, no. 10. pp. 17–18.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Richards 1998, p. 88.

- ^ Herz, J.C. (9 April 1998). "GAME THEORY; From Hitchhiker Spoofs to Starship Titanic". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ a b Cruickshank, Alex (July 1998). "Starship Titanic: a Douglas Adams oddity". PC Magazine UK. No. 7. p. 403.

- ^ Richards 1998, p. 89.

- ^ "Simon & Schuster Announces Multimedia Deal with Bestselling Science-Fiction Author Douglas Adams". PR Newswire. 13 May 1996. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "Simon & Schuster Interactive unveils 12 new products at E3". Business Wire. 5 June 1997. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Webb 2005, p. 305.

- ^ Ocampo, Jason (30 March 1998). "Another Titanic to arrive this week". Computer Games Strategy Plus. Archived from the original on 2 May 2005. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ a b Webb 2005, p. 306.

- ^ Altman, John (21 April 1998). "Surviving the Starship Titanic Launch Party". Computer Games Strategy Plus. Archived from the original on 6 April 2005. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Douglas Adams' Starship Titanic Lands at Retailers in the U.S.". Business Wire. 3 April 1998.

- ^ "Digital L.A.: Humorist returns to computer games without a hitch". Los Angeles Daily News. 4 June 1998. Retrieved 27 September 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Douglas Adams' Starship Titanic to Release in the U.S. On April 2". Business Wire. 30 March 1998.

- ^ "Flood of Application Software Announced for Macintosh". PR Newswire. 8 July 1998.

- ^ "A New Titanic Sets Sails On Macs March 15". Business Wire. 3 March 1999.

- ^ Fudge, James (25 March 1999). "Douglas Adams Starship Titanic for the Mac ships". Computer Games Strategy Plus. Archived from the original on 6 April 2005. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Sonopress launches DVD-5 version of the Starship Titanic". One to One. UBM plc. 1 June 1999. p. 9.

- ^ "Sonopress launch "Starship Titanic" on DVD". M2 Presswire. 26 April 1999.

- ^ "Starship Titanic Hit by Price Point Iceberg, But Not Sunk Yet". Vol. 5, no. 170. Multimedia Wire. 2 September 1998.

- ^ Staff (November 1998). "Letters; Mys-Adventures". Computer Gaming World. No. 172. p. 34.

- ^ "Simon & Schuster Interactive Looks to Mob Gamers". Multimedia Wire. 25 August 1999.

- ^ Pegoraro, Rob (11 August 2001). "Now Showing on DVD-ROM: Not Much". The Washington Post. p. E1.

- ^ Webb 2005, p. 307.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (17 September 2015). "You can finally play Douglas Adams' Starship Titanic on a modern PC". The Verge. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ Lemon, Marshall (17 September 2015). "Douglas Adams' Starship Titanic Crashes into GOG". The Escapist. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Starship Titanic for PC - GameRankings". Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ Brenesal, Barry (3 August 1998). "Starship Titanic Review". PC Games. Archived from the original on 2 September 1999. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Dixon, Mike (July 1999). "Starship Titanic". MacAddict. Archived from the original on 27 June 2001. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Ardai, Charles (September 1998). "Lost in space". Computer Gaming World. No. 17. pp. 236–237.

- ^ Dickens, Evan (20 May 2002). "Starship Titanic Review". Adventure Gamers. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ Buckman, Chris (31 August 1998). "Starship Titanic Review". IGN. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ Poole, Stephen (July 1998). "Starship Titanic". PC Gamer US. Archived from the original on 5 March 2000. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Wildgoose, David (May 1998). "Starship Titanic". PC Powerplay (24): 80–81.

- ^ Yans, Cindy (5 May 1998). "Starship Titanic". Computer Games Strategy Plus. Archived from the original on 6 April 2005. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Review: "Starship Titanic" doesn't sink, but it's no blockbuster either". CNN. 22 May 1998. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Dulin, Ron (21 April 1998). "Starship Titanic Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Presley, Paul (May 1998). "Starship Titanic". PC Zone (63): 95–96.

- ^ Freund, Jim (1 September 1998). "Starship Titanic". Computer Shopper. 18 (9): 288.

- ^ Young, Jeffrey Adam (5 May 1998). "'Starship' sails on word power". USA Today. p. 8D.

- ^ "Raise the Starship Titanic". Daily News. New York. 26 April 1998. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Brussel, Joe (8 July 1997). "Starship Titanic". Adventure Classic Gaming. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ Oldfield, Andy (19 October 1998). "Bytes". The Independent. p. 12.

- ^ "Second Interactive Achievement Awards - Computer". Interactive.org. Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on 4 November 1999. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Staff (16 February 1999). "The Blister Award: The Best of 1998". The Electric Playground. Archived from the original on 16 August 2000. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Codie Award Winning "Douglas Adams Starship Titanic" Ships for the Mac". Business Wire. 25 March 1999. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Packwood, Lewis (27 January 2015). "The Secret Douglas Adams RPG People Have Been Playing for 15 Years". Kotaku. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Schenkel, Jennifer L. (7 August 2000). "A Hitch in Time". Time. Vol. 156, no. 6. pp. 38–39.

- ^ "Douglas Adams". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. 13 May 2001. p. 7A.

- ^ Niles, Robert (26 April 2001). "'Hitchhiker's Guide' Makes Leap From Fiction to Fact". Los Angeles Times. p. T5.

- ^ H2G2 Editors (23 August 2011). "H2G2 Leaving The BBC Soon!". H2G2. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

Bibliography edit

- Richards, Neil (1998). Starship Titanic: The Official Strategy Guide (1st ed.). Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80147-3.

- Webb, Nick (2005). Wish You Were Here: The Official Biography of Douglas Adams (1st American ed.). Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-47650-6.

External links edit

- Official website

- Starship Titanic at MobyGames