Summary

In mathematics, particularly in combinatorics, a Stirling number of the second kind (or Stirling partition number) is the number of ways to partition a set of n objects into k non-empty subsets and is denoted by or .[1] Stirling numbers of the second kind occur in the field of mathematics called combinatorics and the study of partitions. They are named after James Stirling.

The Stirling numbers of the first and second kind can be understood as inverses of one another when viewed as triangular matrices. This article is devoted to specifics of Stirling numbers of the second kind. Identities linking the two kinds appear in the article on Stirling numbers.

Definition edit

The Stirling numbers of the second kind, written or or with other notations, count the number of ways to partition a set of labelled objects into nonempty unlabelled subsets. Equivalently, they count the number of different equivalence relations with precisely equivalence classes that can be defined on an element set. In fact, there is a bijection between the set of partitions and the set of equivalence relations on a given set. Obviously,

- for n ≥ 0, and for n ≥ 1,

as the only way to partition an n-element set into n parts is to put each element of the set into its own part, and the only way to partition a nonempty set into one part is to put all of the elements in the same part. Unlike Stirling numbers of the first kind, they can be calculated using a one-sum formula:[2]

The Stirling numbers of the second kind may also be characterized as the numbers that arise when one expresses powers of an indeterminate x in terms of the falling factorials[3]

(In particular, (x)0 = 1 because it is an empty product.)

In other words

Notation edit

Various notations have been used for Stirling numbers of the second kind. The brace notation was used by Imanuel Marx and Antonio Salmeri in 1962 for variants of these numbers.[4][5] This led Knuth to use it, as shown here, in the first volume of The Art of Computer Programming (1968).[6][7] According to the third edition of The Art of Computer Programming, this notation was also used earlier by Jovan Karamata in 1935.[8][9] The notation S(n, k) was used by Richard Stanley in his book Enumerative Combinatorics and also, much earlier, by many other writers.[6]

The notations used on this page for Stirling numbers are not universal, and may conflict with notations in other sources.

Relation to Bell numbers edit

Since the Stirling number counts set partitions of an n-element set into k parts, the sum

over all values of k is the total number of partitions of a set with n members. This number is known as the nth Bell number.

Analogously, the ordered Bell numbers can be computed from the Stirling numbers of the second kind via

Table of values edit

Below is a triangular array of values for the Stirling numbers of the second kind (sequence A008277 in the OEIS):

k n

|

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||||

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 1 | ||||||

| 5 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 25 | 10 | 1 | |||||

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 31 | 90 | 65 | 15 | 1 | ||||

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 63 | 301 | 350 | 140 | 21 | 1 | |||

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 127 | 966 | 1701 | 1050 | 266 | 28 | 1 | ||

| 9 | 0 | 1 | 255 | 3025 | 7770 | 6951 | 2646 | 462 | 36 | 1 | |

| 10 | 0 | 1 | 511 | 9330 | 34105 | 42525 | 22827 | 5880 | 750 | 45 | 1 |

As with the binomial coefficients, this table could be extended to k > n, but the entries would all be 0.

Properties edit

Recurrence relation edit

Stirling numbers of the second kind obey the recurrence relation

with initial conditions

For instance, the number 25 in column k = 3 and row n = 5 is given by 25 = 7 + (3×6), where 7 is the number above and to the left of 25, 6 is the number above 25 and 3 is the column containing the 6.

To prove this recurrence, observe that a partition of the objects into k nonempty subsets either contains the -th object as a singleton or it does not. The number of ways that the singleton is one of the subsets is given by

since we must partition the remaining n objects into the available subsets. In the other case the -th object belongs to a subset containing other objects. The number of ways is given by

since we partition all objects other than the -th into k subsets, and then we are left with k choices for inserting object . Summing these two values gives the desired result.

Another recurrence relation is given by

[citation needed]

Simple identities edit

Some simple identities include

This is because dividing n elements into n − 1 sets necessarily means dividing it into one set of size 2 and n − 2 sets of size 1. Therefore we need only pick those two elements;

and

To see this, first note that there are 2n ordered pairs of complementary subsets A and B. In one case, A is empty, and in another B is empty, so 2n − 2 ordered pairs of subsets remain. Finally, since we want unordered pairs rather than ordered pairs we divide this last number by 2, giving the result above.

Another explicit expansion of the recurrence-relation gives identities in the spirit of the above example.

Identities edit

The table in section 6.1 of Concrete Mathematics provides a plethora of generalized forms of finite sums involving the Stirling numbers. Several particular finite sums relevant to this article include.

Explicit formula edit

The Stirling numbers of the second kind are given by the explicit formula:

This can be derived by using inclusion-exclusion to count the surjections from n to k and using the fact that the number of such surjections is .

Additionally, this formula is a special case of the kth forward difference of the monomial evaluated at x = 0:

Because the Bernoulli polynomials may be written in terms of these forward differences, one immediately obtains a relation in the Bernoulli numbers:

The evaluation of incomplete exponential Bell polynomial Bn,k(x1,x2,...) on the sequence of ones equals a Stirling number of the second kind:

Another explicit formula given in the NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions is

Parity edit

The parity of a Stirling number of the second kind is equal to the parity of a related binomial coefficient:

- where

This relation is specified by mapping n and k coordinates onto the Sierpiński triangle.

More directly, let two sets contain positions of 1's in binary representations of results of respective expressions:

One can mimic a bitwise AND operation by intersecting these two sets:

to obtain the parity of a Stirling number of the second kind in O(1) time. In pseudocode:

where is the Iverson bracket.

The parity of a central Stirling number of the second kind is odd if and only if is a fibbinary number, a number whose binary representation has no two consecutive 1s.[11]

Generating functions edit

For a fixed integer n, the ordinary generating function for Stirling numbers of the second kind is given by

where are Touchard polynomials. If one sums the Stirling numbers against the falling factorial instead, one can show the following identities, among others:

and

Which has special case

- .

For a fixed integer k, the Stirling numbers of the second kind have rational ordinary generating function

and have an exponential generating function given by

A mixed bivariate generating function for the Stirling numbers of the second kind is

Lower and upper bounds edit

If and , then

Asymptotic approximation edit

For fixed value of the asymptotic value of the Stirling numbers of the second kind as is given by

If (where o denotes the little o notation) then

A uniformly valid approximation also exists: for all k such that 1 < k < n, one has

where , and is the unique solution to .[14] Relative error is bounded by about .

Maximum for fixed n edit

For fixed , has a single maximum, which is attained for at most two consecutive values of k. That is, there is an integer such that

Looking at the table of values above, the first few values for are

When is large

and the maximum value of the Stirling number can be approximated with

Applications edit

Moments of the Poisson distribution edit

If X is a random variable with a Poisson distribution with expected value λ, then its n-th moment is

In particular, the nth moment of the Poisson distribution with expected value 1 is precisely the number of partitions of a set of size n, i.e., it is the nth Bell number (this fact is Dobiński's formula).

Moments of fixed points of random permutations edit

Let the random variable X be the number of fixed points of a uniformly distributed random permutation of a finite set of size m. Then the nth moment of X is

Note: The upper bound of summation is m, not n.

In other words, the nth moment of this probability distribution is the number of partitions of a set of size n into no more than m parts. This is proved in the article on random permutation statistics, although the notation is a bit different.

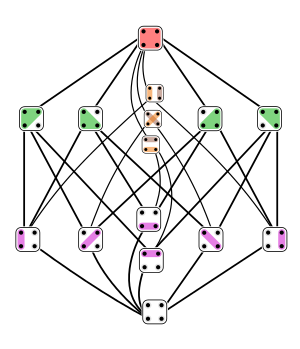

Rhyming schemes edit

The Stirling numbers of the second kind can represent the total number of rhyme schemes for a poem of n lines. gives the number of possible rhyming schemes for n lines using k unique rhyming syllables. As an example, for a poem of 3 lines, there is 1 rhyme scheme using just one rhyme (aaa), 3 rhyme schemes using two rhymes (aab, aba, abb), and 1 rhyme scheme using three rhymes (abc).

Variants edit

r-Stirling numbers of the second kind edit

The r-Stirling number of the second kind counts the number of partitions of a set of n objects into k non-empty disjoint subsets, such that the first r elements are in distinct subsets.[15] These numbers satisfy the recurrence relation

Some combinatorial identities and a connection between these numbers and context-free grammars can be found in [16]

Associated Stirling numbers of the second kind edit

An r-associated Stirling number of the second kind is the number of ways to partition a set of n objects into k subsets, with each subset containing at least r elements.[17] It is denoted by and obeys the recurrence relation

The 2-associated numbers (sequence A008299 in the OEIS) appear elsewhere as "Ward numbers" and as the magnitudes of the coefficients of Mahler polynomials.

Reduced Stirling numbers of the second kind edit

Denote the n objects to partition by the integers 1, 2, ..., n. Define the reduced Stirling numbers of the second kind, denoted , to be the number of ways to partition the integers 1, 2, ..., n into k nonempty subsets such that all elements in each subset have pairwise distance at least d. That is, for any integers i and j in a given subset, it is required that . It has been shown that these numbers satisfy

(hence the name "reduced").[18] Observe (both by definition and by the reduction formula), that , the familiar Stirling numbers of the second kind.

See also edit

- Stirling number

- Stirling numbers of the first kind

- Bell number – the number of partitions of a set with n members

- Stirling polynomials

- Twelvefold way

- Learning materials related to Partition related number triangles at Wikiversity

References edit

- ^ Ronald L. Graham, Donald E. Knuth, Oren Patashnik (1988) Concrete Mathematics, Addison–Wesley, Reading MA. ISBN 0-201-14236-8, p. 244.

- ^ "Stirling Numbers of the Second Kind, Theorem 3.4.1".

- ^ Confusingly, the notation that combinatorialists use for falling factorials coincides with the notation used in special functions for rising factorials; see Pochhammer symbol.

- ^ Transformation of Series by a Variant of Stirling's Numbers, Imanuel Marx, The American Mathematical Monthly 69, #6 (June–July 1962), pp. 530–532, JSTOR 2311194.

- ^ Antonio Salmeri, Introduzione alla teoria dei coefficienti fattoriali, Giornale di Matematiche di Battaglini 90 (1962), pp. 44–54.

- ^ a b Knuth, D.E. (1992), "Two notes on notation", Amer. Math. Monthly, 99 (5): 403–422, arXiv:math/9205211, Bibcode:1992math......5211K, doi:10.2307/2325085, JSTOR 2325085, S2CID 119584305

- ^ Donald E. Knuth, Fundamental Algorithms, Reading, Mass.: Addison–Wesley, 1968.

- ^ p. 66, Donald E. Knuth, Fundamental Algorithms, 3rd ed., Reading, Mass.: Addison–Wesley, 1997.

- ^ Jovan Karamata, Théorèmes sur la sommabilité exponentielle et d'autres sommabilités s'y rattachant, Mathematica (Cluj) 9 (1935), pp, 164–178.

- ^ Sprugnoli, Renzo (1994), "Riordan arrays and combinatorial sums" (PDF), Discrete Mathematics, 132 (1–3): 267–290, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(92)00570-H, MR 1297386

- ^ Chan, O-Yeat; Manna, Dante (2010), "Congruences for Stirling numbers of the second kind" (PDF), Gems in Experimental Mathematics, Contemporary Mathematics, vol. 517, Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, pp. 97–111, doi:10.1090/conm/517/10135, MR 2731094

- ^ a b Rennie, B.C.; Dobson, A.J. (1969). "On stirling numbers of the second kind". Journal of Combinatorial Theory. 7 (2): 116–121. doi:10.1016/S0021-9800(69)80045-1. ISSN 0021-9800.

- ^ L. C. Hsu, Note on an Asymptotic Expansion of the nth Difference of Zero, AMS Vol.19 NO.2 1948, pp. 273--277

- ^ N. M. Temme, Asymptotic Estimates of Stirling Numbers, STUDIES IN APPLIED MATHEMATICS 89:233-243 (1993), Elsevier Science Publishing.

- ^ Broder, A. (1984). The r-Stirling numbers. Discrete Mathematics 49, 241-259

- ^ Triana, J. (2022). r-Stirling numbers of the second kind through context-free grammars. Journal of automata, languages and combinatorics 27(4), 323-333

- ^ L. Comtet, Advanced Combinatorics, Reidel, 1974, p. 222.

- ^ A. Mohr and T.D. Porter, Applications of Chromatic Polynomials Involving Stirling Numbers, Journal of Combinatorial Mathematics and Combinatorial Computing 70 (2009), 57–64.

- Boyadzhiev, Khristo (2012). "Close encounters with the Stirling numbers of the second kind". Mathematics Magazine. 85 (4): 252–266. arXiv:1806.09468. doi:10.4169/math.mag.85.4.252. S2CID 115176876..

- "Stirling numbers of the second kind". PlanetMath..

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Stirling Number of the Second Kind". MathWorld.

- Calculator for Stirling Numbers of the Second Kind

- Set Partitions: Stirling Numbers

- Jack van der Elsen (2005). Black and white transformations. Maastricht. ISBN 90-423-0263-1.