Summary

Sulfite oxidase (EC 1.8.3.1) is an enzyme in the mitochondria of all eukaryotes, with exception of the yeasts.[citation needed] It oxidizes sulfite to sulfate and, via cytochrome c, transfers the electrons produced to the electron transport chain, allowing generation of ATP in oxidative phosphorylation.[5][6][7] This is the last step in the metabolism of sulfur-containing compounds and the sulfate is excreted.

| sulfite oxidase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

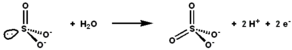

Sulfite oxidase catalyses the oxidation-reduction reaction of sulfite and water, yielding sulfate. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 1.8.3.1 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9029-38-3 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

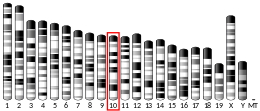

| SUOX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | SUOX, entrez:6821, sulfite oxidase | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 606887 MGI: 2446117 HomoloGene: 394 GeneCards: SUOX | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sulfite oxidase is a metallo-enzyme that utilizes a molybdopterin cofactor and a heme group (in the case of animals). It is one of the cytochromes b5 and belongs to the enzyme super-family of molybdenum oxotransferases that also includes DMSO reductase, xanthine oxidase, and nitrite reductase.

In mammals, the expression levels of sulfite oxidase is high in the liver, kidney, and heart, and very low in spleen, brain, skeletal muscle, and blood.

Structure edit

As a homodimer, sulfite oxidase contains two identical subunits with an N-terminal domain and a C-terminal domain. These two domains are connected by ten amino acids forming a loop. The N-terminal domain has a heme cofactor with three adjacent antiparallel beta sheets and five alpha helices. The C-terminal domain hosts a molybdopterin cofactor that is surrounded by thirteen beta sheets and three alpha helices. The molybdopterin cofactor has a Mo(VI) center, which is bonded to a sulfur from cysteine, an ene-dithiolate from pyranopterin, and two terminal oxygens. It is at this molybdenum center that the catalytic oxidation of sulfite takes place.

The pyranopterin ligand which coordinates the molybdenum centre via the enedithiolate. The molybdenum centre has a square pyramidal geometry and is distinguished from the xanthine oxidase family by the orientation of the oxo group facing downwards rather than up.

Active site and mechanism edit

The active site of sulfite oxidase contains the molybdopterin cofactor and supports molybdenum in its highest oxidation state, +6 (MoVI). In the enzyme's oxidized state, molybdenum is coordinated by a cysteine thiolate, the dithiolene group of molybdopterin, and two terminal oxygen atoms (oxos). Upon reacting with sulfite, one oxygen atom is transferred to sulfite to produce sulfate, and the molybdenum center is reduced by two electrons to MoIV. Water then displaces sulfate, and the removal of two protons (H+) and two electrons (e−) returns the active site to its original state. A key feature of this oxygen atom transfer enzyme is that the oxygen atom being transferred arises from water, not from dioxygen (O2).

Electrons are passed one at a time from the molybdenum to the heme group which reacts with cytochrome c to reoxidize the enzyme. The electrons from this reaction enter the electron transport chain (ETC).

This reaction is generally the rate limiting reaction. Upon reaction of the enzyme with sulfite, it is reduced by 2 electrons. The negative potential seen with re-reduction of the enzyme shows the oxidized state is favoured.

Among the Mo enzyme classes, sulfite oxidase is the most easily oxidized. Although under low pH conditions the oxidative reaction become partially rate limiting.

Deficiency edit

Sulfite oxidase is required to metabolize the sulfur-containing amino acids cysteine and methionine in foods. Lack of functional sulfite oxidase causes a disease known as sulfite oxidase deficiency. This rare but fatal disease causes neurological disorders, mental retardation, physical deformities, the degradation of the brain, and death. Reasons for the lack of functional sulfite oxidase include a genetic defect that leads to the absence of a molybdopterin cofactor and point mutations in the enzyme.[8] A G473D mutation impairs dimerization and catalysis in human sulfite oxidase.[9][10]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000139531 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000049858 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ D'Errico G, Di Salle A, La Cara F, Rossi M, Cannio R (January 2006). "Identification and characterization of a novel bacterial sulfite oxidase with no heme binding domain from Deinococcus radiodurans". J. Bacteriol. 188 (2): 694–701. doi:10.1128/JB.188.2.694-701.2006. PMC 1347283. PMID 16385059.

- ^ Tan WH, Eichler FS, Hoda S, Lee MS, Baris H, Hanley CA, Grant PE, Krishnamoorthy KS, Shih VE (September 2005). "Isolated sulfite oxidase deficiency: a case report with a novel mutation and review of the literature". Pediatrics. 116 (3): 757–66. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1897. PMID 16140720. S2CID 6506338.

- ^ Cohen HJ, Betcher-Lange S, Kessler DL, Rajagopalan KV (December 1972). "Hepatic sulfite oxidase. Congruency in mitochondria of prosthetic groups and activity". J. Biol. Chem. 247 (23): 7759–66. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)44588-2. PMID 4344230.

- ^ Karakas E, Kisker C (November 2005). "Structural analysis of missense mutations causing isolated sulfite oxidase deficiency". Dalton Transactions (21): 3459–63. doi:10.1039/b505789m. PMID 16234925.

- ^ Wilson HL, Wilkinson SR, Rajagopalan KV (February 2006). "The G473D mutation impairs dimerization and catalysis in human sulfite oxidase". Biochemistry. 45 (7): 2149–60. doi:10.1021/bi051609l. PMID 16475804.

- ^ Feng C, Tollin G, Enemark JH (May 2007). "Sulfite oxidizing enzymes". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1774 (5): 527–39. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.03.006. PMC 1993547. PMID 17459792.

Further reading edit

- Kisker, C. “Sulfite oxidase”, Messerschimdt, A.; Huber, R.; Poulos, T.; Wieghardt, K.; eds. Handbook of Metalloproteins, vol 2; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd: New York, 2002

- Feng C, Wilson HL, Hurley JK, et al. (2003). "Essential role of conserved arginine 160 in intramolecular electron transfer in human sulfite oxidase". Biochemistry. 42 (42): 12235–42. doi:10.1021/bi0350194. PMID 14567685.

- Lee HF, Mak BS, Chi CS, et al. (2002). "A novel mutation in neonatal isolated sulphite oxidase deficiency". Neuropediatrics. 33 (4): 174–9. doi:10.1055/s-2002-34491. PMID 12368985. S2CID 39922068.

- Steinberg KK, Relling MV, Gallagher ML, et al. (2007). "Genetic studies of a cluster of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cases in Churchill County, Nevada". Environ. Health Perspect. 115 (1): 158–64. doi:10.1289/ehp.9025. PMC 1817665. PMID 17366837.

- Kimura K, Wakamatsu A, Suzuki Y, et al. (2006). "Diversification of transcriptional modulation: large-scale identification and characterization of putative alternative promoters of human genes". Genome Res. 16 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1101/gr.4039406. PMC 1356129. PMID 16344560.

- Wilson HL, Wilkinson SR, Rajagopalan KV (2006). "The G473D mutation impairs dimerization and catalysis in human sulfite oxidase". Biochemistry. 45 (7): 2149–60. doi:10.1021/bi051609l. PMID 16475804.

- Hoffmann C, Ben-Zeev B, Anikster Y, et al. (2007). "Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance spectroscopy in isolated sulfite oxidase deficiency". J. Child Neurol. 22 (10): 1214–21. doi:10.1177/0883073807306260. PMID 17940249. S2CID 24050167.

- Johnson JL, Coyne KE, Garrett RM, et al. (2002). "Isolated sulfite oxidase deficiency: identification of 12 novel SUOX mutations in 10 patients". Hum. Mutat. 20 (1): 74. doi:10.1002/humu.9038. PMID 12112661. S2CID 45465780.

- Woo WH, Yang H, Wong KP, Halliwell B (2003). "Sulphite oxidase gene expression in human brain and in other human and rat tissues". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 305 (3): 619–23. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00833-7. PMID 12763039.

- Feng C, Wilson HL, Tollin G, et al. (2005). "The pathogenic human sulfite oxidase mutants G473D and A208D are defective in intramolecular electron transfer". Biochemistry. 44 (42): 13734–43. doi:10.1021/bi050907f. PMID 16229463.

- Tan WH, Eichler FS, Hoda S, et al. (2005). "Isolated sulfite oxidase deficiency: a case report with a novel mutation and review of the literature". Pediatrics. 116 (3): 757–66. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1897. PMID 16140720. S2CID 6506338.

- Astashkin AV, Johnson-Winters K, Klein EL, et al. (2008). "Structural studies of the molybdenum center of the pathogenic R160Q mutant of human sulfite oxidase by pulsed EPR spectroscopy and 17O and 33S labeling". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (26): 8471–80. doi:10.1021/ja801406f. PMC 2779766. PMID 18529001.

- Dronov R, Kurth DG, Möhwald H, et al. (2008). "Layer-by-layer arrangement by protein-protein interaction of sulfite oxidase and cytochrome c catalyzing oxidation of sulfite". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (4): 1122–3. doi:10.1021/ja0768690. PMID 18177044.

- Edwards MC, Johnson JL, Marriage B, et al. (1999). "Isolated sulfite oxidase deficiency: review of two cases in one family". Ophthalmology. 106 (10): 1957–61. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90408-6. PMID 10519592.

- Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA, et al. (2004). "The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA project: the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC)". Genome Res. 14 (10B): 2121–7. doi:10.1101/gr.2596504. PMC 528928. PMID 15489334.

- Rudolph MJ, Johnson JL, Rajagopalan KV, Kisker C (2003). "The 1.2 A structure of the human sulfite oxidase cytochrome b(5) domain". Acta Crystallogr. D. 59 (Pt 7): 1183–91. doi:10.1107/S0907444903009934. PMID 12832761.

- Feng C, Wilson HL, Hurley JK, et al. (2003). "Role of conserved tyrosine 343 in intramolecular electron transfer in human sulfite oxidase". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (5): 2913–20. doi:10.1074/jbc.M210374200. PMID 12424234.

- Neumann M, Leimkühler S (2008). "Heavy metal ions inhibit molybdoenzyme activity by binding to the dithiolene moiety of molybdopterin in Escherichia coli". FEBS J. 275 (22): 5678–89. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06694.x. PMID 18959753. S2CID 45452761.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. (2002). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916899M. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Wilson HL, Rajagopalan KV (2004). "The role of tyrosine 343 in substrate binding and catalysis by human sulfite oxidase". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (15): 15105–13. doi:10.1074/jbc.M314288200. PMID 14729666.

- Hakonarson H, Qu HQ, Bradfield JP, et al. (2008). "A novel susceptibility locus for type 1 diabetes on Chr12q13 identified by a genome-wide association study". Diabetes. 57 (4): 1143–6. doi:10.2337/db07-1305. PMID 18198356.

External links edit

- Sulfite+oxidase at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Research Activity of Sarkar Group

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Human Sulfite oxidase, mitochondrial