Summary

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC; French: Cour suprême du Canada, CSC) is the highest court in the judicial system of Canada.[2] It comprises nine justices, whose decisions are the ultimate application of Canadian law, and grants permission to between 40 and 75 litigants each year to appeal decisions rendered by provincial, territorial and federal appellate courts. The Supreme Court is bijural, hearing cases from two major legal traditions (common law and civil law) and bilingual, hearing cases in both official languages of Canada (English and French).

| Supreme Court of Canada | |

|---|---|

| Cour suprême du Canada | |

| |

The flag of the Supreme Court (left) and the Cormier Emblem (right)[1] | |

| |

| 45°25′19″N 75°42′20″W / 45.42194°N 75.70556°W | |

| Established | 8 April 1875 |

| Jurisdiction | Canada |

| Location | Ottawa, Ontario |

| Coordinates | 45°25′19″N 75°42′20″W / 45.42194°N 75.70556°W |

| Composition method | Judicial appointments in Canada |

| Authorized by | Constitution Act, 1867 and Supreme Court Act, 1875 |

| Judge term length | Mandatory retirement at age 75 |

| Number of positions | 9 |

| Website | www |

| Chief Justice of Canada | |

| Currently | Richard Wagner |

| Since | 18 December 2017 |

| Lead position ends | 2 April 2032 |

The effects of any judicial decision on the common law, on the interpretation of statutes, or on any other application of law, can, in effect, be nullified by legislation, unless the particular decision of the court in question involves application of the Canadian Constitution, in which case, the decision (in most cases) is completely binding on the legislative branch. This is especially true of decisions which touch upon the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which cannot be altered by the legislative branch unless the decision is overridden pursuant to section 33 (the "notwithstanding clause").

History edit

The creation of the Supreme Court of Canada was provided for by the British North America Act, 1867, renamed in 1982 the Constitution Act, 1867. The first bills for the creation of a federal supreme court, introduced in the Parliament of Canada in 1869 and in 1870, were withdrawn. It was not until 8 April 1875 that a bill was finally passed providing for the creation of a Supreme Court of Canada.[3]

However, prior to 1949, the Supreme Court did not constitute the court of last resort: litigants could appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. Some cases could bypass the Supreme Court and go directly to the Judicial Committee from the provincial courts of appeal. The Supreme Court formally became the court of last resort for criminal appeals in 1933 and for all other appeals in 1949. Cases that were begun prior to those dates remained appealable to the Judicial Committee, and the last case on appeal from the Supreme Court of Canada was not decided until 1959.[4]

The increase in the importance of the Supreme Court was mirrored by the numbers of its members; it was established first with six judges, and these were augmented by an additional member in 1927. In 1949, the bench reached its current composition of nine justices.[citation needed]

Prior to 1949, most of the appointees to the court owed their position to political patronage. Each judge had strong ties to the party in power at the time of their appointment. In 1973, the appointment of a constitutional law professor Bora Laskin as chief justice represented a major turning point for the court. Laskin's federalist and liberal views were shared by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, who recommended Laskin's appointment to the court, but from that appointment onward appointees increasingly either came from academic backgrounds or were well-respected practitioners with several years' experience in appellate courts.[citation needed]

The Constitution Act, 1982, greatly expanded the role of the court in Canadian society by the addition of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which greatly broadened the scope of judicial review. The evolution from the court under Chief Justice Brian Dickson (1984–1990) through to that of Antonio Lamer (1990–2000) witnessed a continuing vigour in the protection of civil liberties. Lamer's criminal law background proved an influence on the number of criminal cases heard by the Court during his time as chief justice. Nonetheless, the Lamer court was more conservative with Charter rights, with only about a 1% success rate for Charter claimants.[citation needed]

Lamer was succeeded as the chief justice by Beverley McLachlin in January 2000. She was the first woman to hold that position.[5] McLachlin's appointment resulted in a more centrist and unified court. Dissenting and concurring opinions were fewer than during the Dickson and Lamer courts. With the 2005 appointments of puisne justices Louise Charron and Rosalie Abella, the court became the world's most gender-balanced national high court with four of its nine members being female.[6][7] Justice Marie Deschamps' retirement on 7 August 2012 caused the number to fall to three;[8] however, the appointment of Suzanne Côté on 1 December 2014 restored the number to four. After serving on the court for 28 years, 259 days (17 years, 341 days as chief justice), McLachlin retired in December 2017. Her successor as the chief justice is Richard Wagner.

Along with the German Federal Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Rights, the Supreme Court of Canada is among the most frequently cited courts in the world.[9]: 21, 27–28

Canadian judiciary edit

The structure of the Canadian court system is pyramidal, a broad base being formed by the various provincial and territorial courts whose judges are appointed by the provincial or territorial governments. At the next level are the provincial and territorial superior trial courts, where judges are appointed by the federal government. Judgments from the superior courts may be appealed to a still higher level, the provincial or territorial superior courts of appeal.

Several federal courts also exist: the Tax Court, the Federal Court, the Federal Court of Appeal, and the Court Martial Appeal Court. Unlike the provincial superior courts, which exercise inherent or general jurisdiction, the jurisdiction of federal courts and provincially appointed provincial courts are limited by statute. In all, there are over 1,000 federally appointed judges at various levels across Canada.

Appellate process edit

The Supreme Court rests at the apex of the judicial pyramid. This institution hears appeals from the provincial courts of last resort, usually the provincial or territorial courts of appeal, and the Federal Court of Appeal, although in some matters appeals come straight from the trial courts, as in the case of publication bans and other orders that are otherwise not appealable.

In most cases, permission to appeal must first be obtained from the court. Motions for leave to appeal to the court are generally heard by a panel of three of its judges and a simple majority is determinative. By convention, this panel never explains why it grants or refuses leave in any particular case, but the court typically hears cases of national importance or where the case allows it to settle an important issue of law. Leave is rarely granted, meaning that for most litigants, provincial courts of appeal are courts of last resort. But leave to appeal is not required for some cases, primarily indictable criminal cases in which at least one appellate judge (on the relevant provincial court of appeal) dissented on a point of law, and appeals from provincial reference cases.

A final source of cases is the power of the federal government to submit reference cases. In such cases, the Supreme Court is required to give an opinion on questions referred to it by the Governor in Council (the Cabinet). However, in many cases, including the most recent same-sex marriage reference, the Supreme Court has declined to answer a question from the Cabinet. In that case, the court said it would not decide if same-sex marriages were required by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, because the government had announced it would change the law regardless of its opinion, and subsequently did.

Constitutional interpretation edit

The Supreme Court thus performs a unique function. It can be asked by the Governor-in-Council to hear references considering important questions of law. Such referrals may concern the constitutionality or interpretation of federal or provincial legislation, or the division of powers between federal and provincial spheres of government. Any point of law may be referred in this manner. However, the Court is not often called upon to hear references. References have been used to re-examine criminal convictions that have concerned the country as in the cases of David Milgaard and Steven Truscott.

The Supreme Court has the ultimate power of judicial review over Canadian federal and provincial laws' constitutional validity. If a federal or provincial law has been held contrary to the division of power provisions of one of the various constitution acts, the legislature or parliament must either live with the result, amend the law so that it complies, or obtain an amendment to the constitution. If a law is declared contrary to certain sections of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Parliament or the provincial legislatures may make that particular law temporarily valid again against by using the "override power" of the notwithstanding clause. In one case, the Quebec National Assembly invoked this power to override a Supreme Court decision (Ford v Quebec (AG)) that held that one of Quebec's language laws banning the display of English commercial signs was inconsistent with the Charter. Saskatchewan has also used it to uphold its labour laws. This override power can be exercised for five years, after which time the override must be renewed or the decision comes into force.

In some cases, the court may stay the effect of its judgments so that unconstitutional laws continue in force for a period of time. Usually, this is done to give Parliament or a legislature sufficient time to enact a new replacement scheme of legislation. For example, in Reference Re Manitoba Language Rights, the court struck down Manitoba's laws because they were not enacted in the French language, as required by the Constitution. However, the Court stayed its judgment for five years to give Manitoba time to re-enact all its legislation in French. It turned out five years was insufficient so the court was asked, and agreed, to give more time.

Constitutional questions may, of course, also be raised in the normal case of appeals involving individual litigants, governments, government agencies or Crown corporations. In such cases the federal and provincial governments must be notified of any constitutional questions and may intervene to submit a brief and attend oral argument at the court. Usually the other governments are given the right to argue their case in the court, although on rare occasions this has been curtailed and prevented by order of one of the court's judges.

Sessions edit

The Supreme Court sits in three sessions in each calendar year. The first session begins on the fourth Tuesday in January, the second session on the fourth Tuesday in April, and the third session on the first Tuesday in October. The Court determines how long each session will be. Hearings only take place in Ottawa, although litigants can present oral arguments from remote locations by means of a video-conference system. Hearings are open to the public. Most hearings are taped for delayed telecast in both of Canada's official languages. When in session, the court sits Monday to Friday, hearing two appeals a day. A quorum consists of five members for appeals, but a panel of nine justices hears most cases.[citation needed]

On the bench, the chief justice of Canada or, in his or her absence, the senior puisne justice, presides from the centre chair with the other justices seated to his or her right and left by order of seniority of appointment. At sittings, the justices usually appear in black silk robes but they wear their ceremonial robes of bright scarlet trimmed with Canadian white mink in court on special occasions and in the Senate at the opening of each new session of Parliament.[citation needed]

Counsel appearing before the court may use either English or French. The judges can also use either English or French. There is simultaneous translation available to the judges, counsel and to members of the public who are in the audience.

The decision of the court is sometimes – but rarely – rendered orally at the conclusion of the hearing. In these cases, the court may simply refer to the decision of the court below to explain its own reasons. In other cases, the court may announce its decision at the conclusion of the hearing, with reasons to follow.[10][11][12] As well, in some cases, the court may not call on counsel for the respondent, if it has not been convinced by the arguments of counsel for the appellant.[13] In very rare cases, the court may not call on counsel for the appellant and instead calls directly on counsel for the respondent.[14] However, in most cases, the court hears from all counsel and then reserves judgment to enable the justices to write considered reasons. Decisions of the court need not be unanimous – a majority may decide, with dissenting reasons given by the minority. Justices may write separate or joint opinions for any case.

A puisne justice of the Supreme Court is referred to as The Honourable Mr/Madam Justice and the chief justice as Right Honourable. At one time, judges were addressed as "My Lord" or "My Lady" during sessions of the court, but it has since discouraged this style of address and has directed lawyers to use the simpler "Justice", "Mr Justice" or "Madam Justice".[15] The designation "My Lord/My Lady" continues in many provincial superior courts and in the Federal Court of Canada and Federal Court of Appeal, where it is optional.

Every four years, the Judicial Compensation and Benefits Commission makes recommendations to the federal government about the salaries for federally appointed judges, including the judges of the Supreme Court. That recommendation is not legally binding on the federal government, but the federal government is generally required to comply with the recommendation unless there is a very good reason to not do so.[16] The chief justice receives $370,300 while the puisne justices receive $342,800 annually.[17]

Appointment of justices edit

Justices of the Supreme Court of Canada are appointed on the advice of the prime minister.[18]

The Supreme Court Act limits eligibility for appointment to persons who have been judges of a superior court or members of the bar for ten or more years. Members of the bar or superior judiciary of Quebec, by law, must hold three of the nine positions on the Supreme Court of Canada.[19] This is justified on the basis that Quebec uses civil law, rather than common law, as in the rest of the country. As explained in the reasons in Reference Re Supreme Court Act, ss. 5 and 6, sitting judges of the Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal cannot be appointed to any of Quebec's three seats. By convention, the remaining six positions are divided in the following manner: three from Ontario; two from the western provinces, typically one from British Columbia and one from the prairie provinces, which rotate among themselves (although Alberta is known to cause skips in the rotation); and one from the Atlantic provinces, almost always[clarification needed] from Nova Scotia or New Brunswick.[20] Parliament and the provincial governments have no constitutional role in such appointments, sometimes a point of contention.[21]

In 2006, an interview phase by an ad hoc committee of members of Parliament was added. Justice Marshall Rothstein became the first justice to undergo the new process. The prime minister still has the final say on who becomes the candidate that is recommended to the governor general for appointment to the court. The government proposed an interview phase again in 2008, but a general election and minority parliament intervened with delays such that the Prime Minister recommended Justice Cromwell after consulting the leader of the Opposition.[22]

As of August 2016, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau opened the process of application to change from the above-noted appointment process. Under the revised process, "[any] Canadian lawyer or judge who fits specified criteria can apply for a seat on the Supreme Court, through the Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs."[23][24] Functional bilingualism is now a requirement.[25][26][27]

Justices were originally allowed to remain on the bench for life, but in 1927 a mandatory retirement age of 75 was instituted. They may choose to retire earlier, but can only be removed involuntarily before that age by a vote of the Senate and House of Commons.[28][29]

Current members edit

The current chief justice of Canada is Richard Wagner. He was appointed to the court as a puisne judge on 5 October 2012 and appointed chief justice, 18 December 2017.[30] The nine justices of the Wagner Court are:

Length of tenure edit

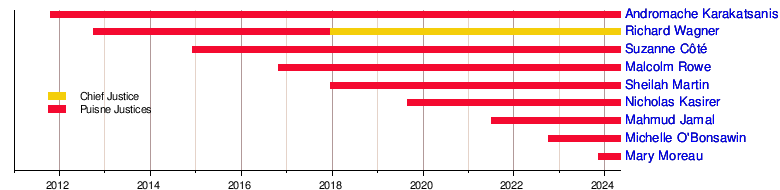

The following graphical timeline depicts the length of each current justice's tenure on the Supreme Court (not their position in the court's order of precedence) as of 23 April 2024.

Andromache Karakatsanis has had the longest tenure of any of the current members of the court, having been appointed in October 2011. Richard Wagner's cumulative tenure is 11 years, 201 days—5 years, 74 days as puisne justice, and 6 years, 127 days as chief justice. Mary Moreau has the briefest tenure, having been appointed 169 days ago. The length of tenure for the other justices are: Suzanne Côté, 9 years, 144 days; Malcom Rowe, 7 years, 178 days; Sheilah Martin, 6 years, 127 days; Nicholas Kasirer, 4 years, 220 days; Mahmud Jamal, 2 years, 297 days; and Michelle O'Bonsawin, 1 year, 235 days.

Rules of the court edit

The Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada are located on the laws-lois.justice.gc.ca website,[39] as well as in the Canada Gazette, as SOR/2002-216 (plus amendments), made pursuant to subsection 97(1) of the Supreme Court Act. Fees and taxes are stipulated near the end.

Law clerks edit

Since 1967, the court has hired law clerks to assist in legal research. Between 1967 and 1982, each puisne justice was assisted by one law clerk and the chief justice had two. From 1982, the number was increased to two law clerks for each justice.[40] Currently, each justice has up to four law clerks.[41]

Building edit

The Supreme Court of Canada Building (French: L’édifice de la Cour suprême du Canada) is located just west of Parliament Hill, at 301 Wellington Street. It is situated on a bluff high above the Ottawa River in downtown Ottawa and is home to the Supreme Court of Canada.[42] It also contains two courtrooms used by the Federal Court and the Federal Court of Appeal.

The building was designed by Ernest Cormier and is known for its Art Deco style[43]—including two candelabrum-style fluted metal lamp standards that flank the entrance and the marble walls and floors of the lobby[44]—contrasting with the châteauesque roof. Construction began in 1939, with the cornerstone laid by Queen Elizabeth, consort of King George VI and later known as the Queen Mother. In her speech, she said, "perhaps it is not inappropriate that this task should be performed by a woman; for woman's position in a civilized society has depended upon the growth of law."[45] The court began hearing cases in the new building by January 1946.

In 2000, the edifice was named by the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada as one of the top 500 buildings produced in Canada during the last millennium.[46] Canada Post issued a commemorative stamp on 9 June 2011, as part of the Architecture Art Déco series.[44]

Two flagstaffs have been erected in front of the building. A flag on one is flown daily, while the other is hoisted only on those days when the court is in session. Also located on the grounds are several statues, including one of Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, by Elek Imredy in 1976, and two—Veritas (Truth) and Justitia (Justice)—by Canadian sculptor Walter S. Allward. Inside there are busts of several chief justices: John Robert Cartwright (1967–1970), Bora Laskin (1973–1983), Brian Dickson (1984–1990), and Antonio Lamer (1990–2000), all sculpted by Kenneth Phillips Jarvis, a retired Under Treasurer of the Law Society of Upper Canada.[47]

The court was previously housed in the Railway Committee Room and a number of other committee rooms in the Centre Block on Parliament Hill.[48] The court then sat in the Old Supreme Court building on Bank Street, between 1889 and 1945. That structure was demolished in 1955 and the site used as parking for Parliament Hill.

See also edit

- Supreme Court of Canada cases

- List of supreme courts by country

References edit

- ^ a b "Description of Heraldic Emblems". Supreme Court of Canada. 15 March 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Role of the Court". Supreme Court of Canada. 23 May 2014. Archived from the original on 5 August 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Hulmes, F. (1986). "The Supreme Court of Canada: History of the Institution". Canadian Journal of Political Science. 19 (2). JSTOR 3227510. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Ponoka-Calmar Oils Ltd. and another v Earl F. Wakefield Co. And others [1959] UKPC 20, [1960] AC 18 (7 October 1959), P.C. (on appeal from Canada)

- ^ "The Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin, P.C., C.C." Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "New judges fill gaps in spectrum". The Globe and Mail. 5 October 2004. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ " "Two women named to Canada's supreme court". UPI. 4 October 2004. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ "Supreme Court loses third veteran judge in a year with Justice Marie Deschamps' departure". Toronto Star. 18 May 2012. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Hirschl, Ran (August 2014), "The View from the Bench: Where the Comparative Judicial Imagination Travels", Comparative Matters: The Renaissance of Comparative Constitutional Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 20–76, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198714514.003.0002, ISBN 978-0-19-871451-4, retrieved 6 September 2022,

Accordingly, the Supreme Court of Canada, the German Federal Constitutional Court, and the European Court of Human Rights have emerged as three of the most frequently cited courts in the world.

- ^ R. v. Beare; R. v. Higgins Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, [1988] 2 S.C.R. 387, para. 19.

- ^ Consortium Developments (Clearwater) Ltd. v. Sarnia (City) Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, [1998] 3 S.C.R. 3, para. 1.

- ^ Rothmans, Benson & Hedges Inc. v. Saskatchewan Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 2005 SCC 13, [2005] 1 S.C.R. 188, para. 1.

- ^ Whitbread v. Walley Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, [1990] 3 S.C.R. 1273, para. 2.

- ^ Rothmans, Benson & Hedges Inc. v. Saskatchewan Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 2005 SCC 13, [2005] 1 S.C.R. 188.

- ^ Canada, Supreme Court of (1 January 2001). "Supreme Court of Canada - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)". www.scc-csc.ca. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Provincial Court Judges’ Assn. of New Brunswick v. New Brunswick (Minister of Justice); Ontario Judges’ Assn. v. Ontario (Management Board); Bodner v. Alberta; Conférence des juges du Québec v. Quebec (Attorney General); Minc v. Quebec (Attorney General) Archived 19 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, [2005] 2 S.C.R. 286, 2005 SCC 44, para. 21.

- ^ "Judges Act". Minister and Attorney General of Canada. 9 June 2014. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Amelio, Julia (6 June 2019). "Supreme Court Appointment Process and the Prime Minister of the Day - Centre for Constitutional Studies". www.constitutionalstudies.ca/. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Supreme Court Act Archived 30 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine, s. 6.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (6 January 2017). "History of the Canadian Labour Force Survey, 1945 to 2016". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "The Legislative Process - Stages in the Legislative Process". www.ourcommons.ca. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "The Governor General's Decision to Prorogue Parliament: A Dangerous Precedent". www.sfu.ca. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ Justin Trudeau (2 August 2016). "Why Canada has a new way to choose Supreme Court judges". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ "New process for judicial appointments to the Supreme Court of Canada" (Press release). Government of Canada. 2 August 2016. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ "Prime Minister announces advisory board to select the next Supreme Court justice". Prime Minister of Canada. 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ "The Hill: The wrangle over bilingualism". www.lawtimesnews.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ "Applicants for SCC vacancy must be bilingual Westerners or Northerners". www.canadianlawyermag.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ An Act to amend the Supreme Court Act, S.C. 1927, c. 38, s. 2.

- ^ Supreme Court Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. S-26, s. 9.

- ^ a b "The Right Honourable Richard Wagner, P.C., Chief Justice of Canada". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "The Honourable Andromache Karakatsanis". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "The Honourable Suzanne Côté". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "The Honourable Malcolm Rowe". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "The Honourable Sheilah L. Martin". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "The Honourable Nicholas Kasirer". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ "The Honourable Mahmud Jamal". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ "The Honourable Michelle O'Bonsawin". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ "The Honourable Mary T. Moreau". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. 6 November 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ laws-lois.justice.gc.ca

- ^ The Supreme Court of Canada / La Cour Suprême du Canada. Ottawa: Supreme Court of Canada. 2005. p. 7.

- ^ "Law Clerk Program". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "SCC Building". Ottawa, Ontario: Supreme Court of Canada. January 2001. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "1940 – Supreme Court of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario". archiseek.com. 10 December 2009. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Supreme Court of Canada, Ottawa" (Press release). Canada Post. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "At Home in Canada": Royalty at Canada's Historic Places, Canad's Historic Places, retrieved 30 April 2023

- ^ Cook, Marcia (11 May 2000). "Cultural consequence". Ottawa Citizen. Canwest. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ "In Memoriam: Kenneth Jarvis 1927–2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Kathryn Blaze Carlson (11 May 2011). "Liberals take their leave of the Railway Room". National Post.

Further reading edit

- McCormick, Peter (2000), Supreme at last: the evolution of the Supreme Court of Canada, J. Lorimer, ISBN 1-55028-693-5, archived from the original on 15 August 2021, retrieved 21 November 2020

- Ostberg, Cynthia L (2007), Attitudinal decision making in the Supreme Court of Canada, UBC Press, ISBN 978-0-7748-1312-9, archived from the original on 16 August 2021, retrieved 21 November 2020

- Songer, Donald R (2008), The transformation of the Supreme Court of Canada: an empirical examination, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-9689-0, archived from the original on 14 August 2021, retrieved 21 November 2020

External links edit

- Supreme Court of Canada website

- Supreme Court of Canada Library Catalogue

- Opinions of the Supreme Court of Canada

- searchable database of SCC decisions (to 1948, with select older cases) via CanLII

- Supreme Court of Canada from www.marianopolis.edu

- Explore the Virtual Charter—Charter of Rights website with video, audio and the Charter in more than twenty languages

- The appointment process and reform Archived 27 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- SCC building from official site

- SCC Building Archived 31 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine