-

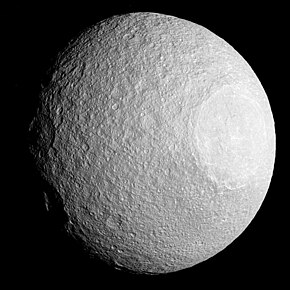

Tethys—Trailing hemisphere—Standard processing

(11 April 2015). -

Tethys—Trailing hemisphere—Enhanced processing

(11 April 2015). -

Tethys—Trailing hemisphere—Enhanced-color

(11 April 2014)

Summary

Tethys (/ˈtiːθɪs, ˈtɛθɪs/), or Saturn III, is the fifth-largest moon of Saturn, measuring about 1,060 km (660 mi) across. It was discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1684, and is named after the titan Tethys of Greek mythology.

Tethys imaged by the Cassini orbiter, April 2015 | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | G. D. Cassini |

| Discovery date | 11 March 1684 |

| Designations | |

Designation | Saturn III |

| Pronunciation | /ˈtɛθəs/[1] or /ˈtiːθəs/[2] |

Named after | Τηθύς Tēthys |

| Adjectives | Tethyan[3] /ˈtɛθiən, ˈtiː-/[1][2] |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| 294619 km | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0001[4] |

| 1.887802 d[5] | |

Average orbital speed | 11.35 km/s |

| Inclination | 1.12° (to Saturn's equator) |

| Satellite of | Saturn |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 1076.8 × 1057.4 × 1052.6 km[6] |

Mean radius | 531.1±0.6 km[6][7] |

| Mass | 6.1749×1020 kg[7] (1.03×10−4 Earths) |

Mean density | 0.9840±0.0033 g/cm3[7] |

| 0.146 m/s2 [a] | |

| 0.394 km/s[b] | |

| synchronous[8] | |

| zero | |

| Albedo | |

| Temperature | 86±1 K[12] |

| 10.2[13] | |

Tethys has a low density of 0.98 g/cm3, the lowest of all the major moons in the solar system, indicating that it is made of water ice with just a small fraction of rock. This was confirmed by the spectroscopy of its surface, which identified water ice as the dominant surface material. A further, smaller amount of an unidentified dark material is present as well. The surface of Tethys is very bright, being the second-brightest of the moons of Saturn after Enceladus, and neutral in color.

Tethys is heavily cratered and cut by a number of large faults/graben. The largest impact crater, Odysseus, is about 400 km in diameter, whereas the largest graben, Ithaca Chasma, is about 100 km wide and more than 2,000 km long; the two surface features may be related. A small part of the surface is covered by smooth plains that may be cryovolcanic in origin. Like the other regular moons of Saturn, Tethys formed from the Saturnian sub-nebula—a disk of gas and dust that surrounded Saturn soon after its formation.

Tethys has been approached and observed by several space probes, including Pioneer 11 (1979), Voyager 1 (1980) and Voyager 2 (1981), with Cassini-Huygens observing the moon the most, and in greatest detail, during its extensive mission to the Saturnian system (2004-2017).

Discovery and naming edit

Tethys was discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1684 together with Dione, another moon of Saturn. He had also discovered two moons, Rhea and Iapetus earlier, in 1671–72.[14] Cassini observed all of these moons using a large aerial telescope he set up on the grounds of the Paris Observatory.[15]

Cassini named the four new moons as Sidera Lodoicea ("the stars of Louis") to honour king Louis XIV of France.[16] By the end of the seventeenth century, astronomers fell into the habit of referring to them and Titan as Saturn I through Saturn V (Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Titan, Iapetus).[14] Once Mimas and Enceladus were discovered in 1789 by William Herschel, the numbering scheme was extended to Saturn VII by bumping the older five moons up two slots. The discovery of Hyperion in 1848 changed the numbers one last time, bumping Iapetus up to Saturn VIII. Henceforth, the numbering scheme would remain fixed.

The modern names of all seven satellites of Saturn come from John Herschel (son of William Herschel, discoverer of Mimas and Enceladus).[14] In his 1847 publication Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope,[17] he suggested the names of the Titans, sisters and brothers of Kronos (the Greek analogue of Saturn), be used. Tethys is named after the titaness Tethys.[14] It is also designated Saturn III or S III Tethys.

The name Tethys has two customary pronunciations, with either a 'long' or a 'short' e: /ˈtiːθɪs/[18] or /ˈtɛθɪs/.[19] (This might be a US/UK difference.)[citation needed] The conventional adjectival form of the name is Tethyan,[20] again with either a long or a short e.

Orbit edit

Tethys orbits Saturn at a distance of about 295,000 km (about 4.4 Saturn's radii) from the center of the planet. Its orbital eccentricity is negligible, and its orbital inclination is about 1°. Tethys is locked in an inclination resonance with Mimas; however, due to the low gravity of the respective bodies, this interaction does not cause any noticeable orbital eccentricity or tidal heating.[21]

The Tethyan orbit lies deep inside the magnetosphere of Saturn, so the plasma co-rotating with the planet strikes the trailing hemisphere of the moon. Tethys is also subject to constant bombardment by the energetic particles (electrons and ions) present in the magnetosphere.[22]

Trojans edit

Tethys has two co-orbital moons, Telesto and Calypso, orbiting near Tethys's trojan points L4 (60° ahead) and L5 (60° behind) respectively.

| Name | Diameter (km) | Semi-major axis (km) | Mass (kg) | Discovery date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tethys | 1 062 | 294 619 | (6. 175 ± 0.000 146) × 1020 | 11 March 1684 |

| Telesto | 24.6 ± 0.6 | 295 000 | ≈4 × 1015 | 8 April 1980 |

| Calypso | 19 ± 0.8 | 295 000 | ≈2 × 1015 | 13 March 1980 |

Physical characteristics edit

Tethys is the 16th-largest moon in the Solar System, with a radius of 531 km.[6] Its mass is about 6.17×1020 kg(0.000103 Earth mass),[7] which is less than 1% of the Moon. Despite its relatively small mass, it is more massive than all known moons smaller than itself combined.[23]

The density of Tethys is 0.98 g/cm3, indicating that it is composed almost entirely of water-ice.[24] It is also the fifth-largest of Saturn's moons. It is not known whether Tethys is differentiated into a rocky core and ice mantle. However, if it is differentiated, the radius of the core does not exceed 145 km, and its mass is below 6% of the total mass. Due to the action of tidal and rotational forces, Tethys has the shape of triaxial ellipsoid. The dimensions of this ellipsoid are consistent with it having a homogeneous interior.[24] The existence of a subsurface ocean—a layer of liquid salt water in the interior of Tethys—is considered unlikely.[25]

The surface of Tethys is one of the most reflective (at visual wavelengths) in the Solar System, with a visual albedo of 1.229. This very high albedo is the result of the sandblasting of particles from Saturn's E-ring, a faint ring composed of small, water-ice particles generated by Enceladus's south polar geysers.[9] The radar albedo of the Tethyan surface is also very high.[26] The leading hemisphere of Tethys is brighter by 10–15% than the trailing one.[27]

The high albedo indicates that the surface of Tethys is composed of almost pure water ice with only a small amount of darker materials. The visible spectrum of Tethys is flat and featureless, whereas in the near-infrared strong water ice absorption bands at 1.25, 1.5, 2.0 and 3.0 μm wavelengths are visible.[27] No compound other than crystalline water ice has been unambiguously identified on Tethys.[28] (Possible constituents include organics, ammonia and carbon dioxide.) The dark material in the ice has the same spectral properties as seen on the surfaces of the dark Saturnian moons—Iapetus and Hyperion. The most probable candidate is nanophase iron or hematite.[29] Measurements of the thermal emission as well as radar observations by the Cassini spacecraft show that the icy regolith on the surface of Tethys is structurally complex[26] and has a large porosity exceeding 95%.[30]

Surface features edit

Color patterns edit

The surface of Tethys has a number of large-scale features distinguished by their color and sometimes brightness. The trailing hemisphere gets increasingly red and dark as the anti-apex of motion is approached. This darkening is responsible for the hemispheric albedo asymmetry mentioned above.[31] The leading hemisphere also reddens slightly as the apex of the motion is approached, although without any noticeable darkening.[31] Such a bifurcated color pattern results in the existence of a bluish band between hemispheres following a great circle that runs through the poles. This coloration and darkening of the Tethyan surface is typical for Saturnian middle-sized satellites. Its origin may be related to a deposition of bright ice particles from the E-ring onto the leading hemispheres and dark particles coming from outer satellites on the trailing hemispheres. The darkening of the trailing hemispheres can also be caused by the impact of plasma from the magnetosphere of Saturn, which co-rotates with the planet.[32]

On the leading hemisphere of Tethys spacecraft observations have found a dark bluish band spanning 20° to the south and north from the equator. The band has an elliptical shape getting narrower as it approaches the trailing hemisphere. A comparable band exists only on Mimas.[33] The band is almost certainly caused by the influence of energetic electrons from the Saturnian magnetosphere with energies greater than about 1 MeV. These particles drift in the direction opposite to the rotation of the planet and preferentially impact areas on the leading hemisphere close to the equator.[34] Temperature maps of Tethys obtained by Cassini, have shown this bluish region is cooler at midday than surrounding areas, giving the satellite a "Pac-man"-like appearance at mid-infrared wavelengths.[35]

Geology edit

The surface of Tethys mostly consists of hilly cratered terrain dominated by craters more than 40 km in diameter. A smaller portion of the surface is represented by the smooth plains on the trailing hemisphere. There are also a number of tectonic features such as chasmata and troughs.[36]

The western part of the leading hemisphere of Tethys is dominated by a large impact crater called Odysseus, whose 450 km diameter is nearly 2/5 of that of Tethys itself. The crater is now quite flat – more precisely, its floor conforms to Tethys's spherical shape. This is most likely due to the viscous relaxation of the Tethyan icy crust over geologic time. Nevertheless, the rim crest of Odysseus is elevated by approximately 5 km above the mean satellite radius. The central complex of Odysseus features a central pit 2–4 km deep surrounded by massifs elevated by 6–9 km above the crater floor, which itself is about 3 km below the average radius.[36]

The second major feature seen on Tethys is a huge valley called Ithaca Chasma, about 100 km wide and 3 km deep. It is more than 2,000 km in length, approximately 3/4 of the way around Tethys's circumference.[36] Ithaca Chasma occupies about 10% of the surface of Tethys. It is approximately concentric with Odysseus—a pole of Ithaca Chasma lies only approximately 20° from the crater.[37]

It is thought that Ithaca Chasma formed as Tethys's internal liquid water solidified, causing the moon to expand and cracking the surface to accommodate the extra volume within. The subsurface ocean may have resulted from a 2:3 orbital resonance between Dione and Tethys early in the Solar System's history that led to orbital eccentricity and tidal heating of Tethys's interior. The ocean would have frozen after the moons escaped from the resonance.[38] There is another theory about the formation of Ithaca Chasma: when the impact that caused the great crater Odysseus occurred, the shock wave traveled through Tethys and fractured the icy, brittle surface. In this case Ithaca Chasma would be the outermost ring graben of Odysseus.[36] However, age determination based on crater counts in high-resolution Cassini images showed that Ithaca Chasma is older than Odysseus making the impact hypothesis unlikely.[37]

The smooth plains on the trailing hemisphere are approximately antipodal to Odysseus, although they extend about 60° to the northeast from the exact antipode. The plains have a relatively sharp boundary with the surrounding cratered terrain. The location of this unit near Odysseus' antipode argues for a connection between the crater and plains. The latter can be a result of focusing the seismic waves produced by the impact in the center of the opposite hemisphere. However the smooth appearance of the plains together with their sharp boundaries (impact shaking would have produced a wide transitional zone) indicates that they formed by endogenic intrusion, possibly along the lines of weakness in the Tethyan lithosphere created by Odysseus impact.[36][39]

Impact craters and chronology edit

The majority of Tethyan impact craters are of a simple central peak type. Those more than 150 km in diameter show more complex peak ring morphology. Only Odysseus crater has a central depression resembling a central pit. Older impact craters are somewhat shallower than young ones implying a degree of relaxation.[40]

The density of impact craters varies across the surface of Tethys. The higher the crater density, the older the surface. This allows scientists to establish a relative chronology for Tethys. The cratered terrain is the oldest unit likely dating back to the Solar System formation 4.56 billion years ago.[41] The youngest unit lies within Odysseus crater with an estimated age from 3.76 to 1.06 billion years, depending on the absolute chronology used.[41] Ithaca Chasma is older than Odysseus.[42]

Origin and evolution edit

Saturn's rings

Tethys is thought to have formed from an accretion disc or subnebula; a disc of gas and dust that existed around Saturn for some time after its formation.[43] The low temperature at the position of Saturn in the Solar nebular means that water ice was the primary solid from which all moons formed. Other more volatile compounds like ammonia and carbon dioxide were likely present as well, though their abundances are not well constrained.[44]

The extremely water-ice-rich composition of Tethys remains unexplained. The conditions in the Saturnian sub-nebula likely favored conversion of the molecular nitrogen and carbon monoxide into ammonia and methane, respectively.[45] This can partially explain why Saturnian moons including Tethys contain more water ice than outer Solar System bodies like Pluto or Triton as the oxygen freed from carbon monoxide would react with the hydrogen forming water.[45] One of the most interesting explanations proposed is that the rings and inner moons accreted from the tidally stripped ice-rich crust of a Titan-like moon before it was swallowed by Saturn.[46]

The accretion process probably lasted for several thousand years before the moon was fully formed. Models suggest that impacts accompanying accretion caused heating of Tethys's outer layer, reaching a maximum temperature of around 155 K at a depth of about 29 km.[47] After the end of formation due to thermal conduction, the subsurface layer cooled and the interior heated up.[48] The cooling near-surface layer contracted and the interior expanded. This caused strong extensional stresses in Tethys's crust reaching estimates of 5.7 MPa, which likely led to cracking.[49]

Because Tethys lacks substantial rock content, the heating by decay of radioactive elements is unlikely to have played a significant role in its further evolution.[50] This also means that Tethys may have never experienced any significant melting unless its interior was heated by tides. They may have occurred, for instance, during the passage of Tethys through an orbital resonance with Dione or some other moon.[21] Still, present knowledge of the evolution of Tethys is very limited.

Exploration edit

Pioneer 11 flew by Saturn in 1979, and its closest approach to Tethys was 329,197 km on 1 September 1979.[51]

One year later, on 12 November 1980, Voyager 1 flew 415,670 km from Tethys.[52] Its twin spacecraft, Voyager 2, passed as close as 93,010 km from the moon on 26 August 1981.[53][54][12] Although both spacecraft took images of Tethys, the resolution of Voyager 1's images did not exceed 15 km, and only those obtained by Voyager 2 had a resolution as high as 2 km.[12] The first geological feature discovered in 1980 by Voyager 1 was Ithaca Chasma.[52] Later in 1981 Voyager 2 revealed that it almost circled the moon running for 270°. Voyager 2 also discovered the Odysseus crater.[12] Tethys was the Saturnian satellite most fully imaged by the Voyagers.[36]

The Cassini spacecraft entered orbit around Saturn in 2004. During its primary mission from June 2004 through June 2008 it performed one very close targeted flyby of Tethys on 24 September 2005 at the distance of 1,503 km. In addition to this flyby the spacecraft performed many non-targeted flybys during its primary and equinox missions since 2004, at distances of tens of thousands of kilometers.[53][55][56]

Another flyby of Tethys took place on 14 August 2010 (during the solstice mission) at a distance of 38,300 km, when the fourth-largest crater on Tethys, Penelope, which is 207 km wide, was imaged.[57] More non-targeted flybys were planned for the solstice mission in 2011–2017.[58]

Cassini's observations allowed high-resolution maps of Tethys to be produced with the resolution of 0.29 km.[59] The spacecraft obtained spatially resolved near-infrared spectra of Tethys showing that its surface is made of water ice mixed with a dark material,[27] whereas the far-infrared observations constrained the bolometric bond albedo.[11] The radar observations at the wavelength of 2.2 cm showed that the ice regolith has a complex structure and is very porous.[26] The observations of plasma in the vicinity of Tethys demonstrated that it is a geologically dead body producing no new plasma in the Saturnian magnetosphere.[60]

Future missions to Tethys and the Saturn system are uncertain, but one possibility is the Titan Saturn System Mission.

Quadrangles edit

Tethys is divided into 15 quadrangles:

- North Polar Area

- Anticleia

- Odysseus

- Alcinous

- Telemachus

- Circe

- Polycaste

- Theoclymenus

- Penelope

- Salmoneus

- Ithaca Chasma

- Hermione

- Melanthius

- Antinous

- South Polar Area

Tethys in fiction edit

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ Surface gravity derived from the mass m, the gravitational constant G and the radius r : .

- ^ Escape velocity derived from the mass m, the gravitational constant G and the radius r : √2Gm/r.

Citations edit

- ^ a b "Tethys". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b "Tethys". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

- ^ JPL (2009) Cassini Equinox Mission: Tethys

- ^ Jacobson 2010 SAT339.

- ^ Williams D. R. (22 February 2011). "Saturnian Satellite Fact Sheet". NASA. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ a b c Roatsch Jaumann et al. 2009, p. 765, Tables 24.1–2.

- ^ a b c d Jacobson, Robert. A. (1 November 2022). "The Orbits of the Main Saturnian Satellites, the Saturnian System Gravity Field, and the Orientation of Saturn's Pole*". The Astronomical Journal. 164 (5): 199. Bibcode:2022AJ....164..199J. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac90c9. S2CID 252992162.

- ^ Jaumann Clark et al. 2009, p. 659.

- ^ a b Verbiscer French et al. 2007.

- ^ Jaumann Clark et al. 2009, p. 662, Table 20.4.

- ^ a b Howett Spencer et al. 2010, p. 581, Table 7.

- ^ a b c d Stone & Miner 1982.

- ^ Observatorio ARVAL.

- ^ a b c d Van Helden 1994.

- ^ Price 2000, p. 279.

- ^ Cassini 1686–1692.

- ^ Lassell 1848.

- ^ "Tethys". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

"Tethys". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. - ^ "Tethys". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

"Tethys". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. - ^ "Tethys". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

"Tethys". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. - ^ a b Matson Castillo-Rogez et al. 2009, pp. 604–05.

- ^ Khurana Russell et al. 2008, pp. 466–67.

- ^ Williams, Matt (23 October 2015). "Saturn's Moon Tethys". Universe Today. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ a b Thomas Burns et al. 2007.

- ^ Hussmann Sohl et al. 2006.

- ^ a b c Ostro West et al. 2006.

- ^ a b c Filacchione Capaccioni et al. 2007.

- ^ Jaumann Clark et al. 2009, pp. 651–654.

- ^ Jaumann Clark et al. 2009, pp. 654–656.

- ^ Carvano Migliorini et al. 2007.

- ^ a b Schenk Hamilton et al. 2011, pp. 740–44.

- ^ Schenk Hamilton et al. 2011, pp. 750–53.

- ^ Schenk Hamilton et al. 2011, pp. 745–46.

- ^ Schenk Hamilton et al. 2011, pp. 751–53.

- ^ "Cassini Finds a Video Gamers' Paradise at Saturn". NASA. 26 November 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Moore Schenk et al. 2004, pp. 424–30.

- ^ a b Jaumann Clark et al. 2009, pp. 645–46, 669.

- ^ Chen & Nimmo 2008.

- ^ Jaumann Clark et al. 2009, pp. 650–51.

- ^ Jaumann Clark et al. 2009, p. 642.

- ^ a b Dones Chapman et al. 2009, pp. 626–30.

- ^ Giese et al. 2007.

- ^ Johnson & Estrada 2009, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Matson Castillo-Rogez et al. 2009, pp. 582–83.

- ^ a b Johnson & Estrada 2009, pp. 65–68.

- ^ Canup 2010.

- ^ Squyres Reynolds et al. 1988, p. 8788, Table 2.

- ^ Squyres Reynolds et al. 1988, pp. 8791–92.

- ^ Hillier & Squyres 1991.

- ^ Matson Castillo-Rogez et al. 2009, p. 590.

- ^ Muller, Pioneer 11 Full Mission Timeline.

- ^ a b Stone & Miner 1981.

- ^ a b Muller, Missions to Tethys.

- ^ Voyager Mission Description.

- ^ Jaumann Clark et al. 2009, pp. 639–40, Table 20.2 at p. 641.

- ^ Seal & Buffington 2009, pp. 725–26.

- ^ Cook 2010.

- ^ Cassini Solstice Mission.

- ^ Roatsch Jaumann et al. 2009, p. 768.

- ^ Khurana Russell et al. 2008, pp. 472–73.

References edit

- Canup, R. M. (12 December 2010). "Origin of Saturn's rings and inner moons by mass removal from a lost Titan-sized satellite". Nature. 468 (7326): 943–6. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..943C. doi:10.1038/nature09661. PMID 21151108. S2CID 4326819.

- Carvano, J. M.; Migliorini, A.; Barucci, A.; Segura, M.; CIRS Team (April 2007). "Constraining the surface properties of Saturn's icy moons, using Cassini/CIRS emissivity spectra". Icarus. 187 (2): 574–583. Bibcode:2007Icar..187..574C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.09.008.

- Cassini, G. D. (1686–1692). "An Extract of the Journal Des Scavans. Of April 22 st. N. 1686. Giving an Account of Two New Satellites of Saturn, Discovered Lately by Mr. Cassini at the Royal Observatory at Paris". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 16 (179–191): 79–85. Bibcode:1686RSPT...16...79C. doi:10.1098/rstl.1686.0013. JSTOR 101844. S2CID 186210940.

- "Cassini Solstice Mission: Saturn Tour Dates: 2011". JPL/NASA. Archived from the original on 19 September 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- Chen, E. M. A.; Nimmo, F. (10–14 March 2008). "Thermal and Orbital Evolution of Tethys as Constrained by Surface Observations" (PDF). 39th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, (Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIX). League City, Texas. p. 1968. LPI Contribution No. 1391. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Cook, Jia-Rui C. (16 August 2010). "Move Over Caravaggio: Cassini's Light and Dark Moons". JPL/NASA. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- Dones, L.; Chapman, C. R.; McKinnon, W. B.; Melosh, H. J.; Kirchoff, M. R.; Neukum, G.; Zahnle, K. J. (2009). "Icy Satellites of Saturn: Impact Cratering and Age Determination". Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. pp. 613–635. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_19. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9.

- Filacchione, G.; Capaccioni, F.; McCord, T. B.; Coradini, A.; Cerroni, P.; Bellucci, G.; Tosi, F.; d'Aversa, E.; Formisano, V.; Brown, R. H.; Baines, K. H.; Bibring, J. P.; Buratti, B. J.; Clark, R. N.; Combes, M.; Cruikshank, D. P.; Drossart, P.; Jaumann, R.; Langevin, Y.; Matson, D. L.; Mennella, V.; Nelson, R. M.; Nicholson, P. D.; Sicardy, B.; Sotin, C.; Hansen, G.; Hibbitts, K.; Showalter, M.; Newman, S. (January 2007). "Saturn's icy satellites investigated by Cassini-VIMS: I. Full-disk properties: 350–5100 nm reflectance spectra and phase curves". Icarus. 186 (1): 259–290. Bibcode:2007Icar..186..259F. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.08.001.

- Giese, B.; Wagner, R.; Neukum, G.; Helfenstein, P.; Thomas, P. C. (2007). "Tethys: Lithospheric thickness and heat flux from flexurally supported topography at Ithaca Chasma" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (21): 21203. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3421203G. doi:10.1029/2007GL031467.

- Van Helden, Albert (August 1994). "Naming the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn" (PDF). The Newsletter of the Historical Astronomy Division of the American Astronomical Society (32): 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- Hillier, John; Squyres, Steven W. (August 1991). "Thermal stress tectonics on the satellites of Saturn and Uranus". Journal of Geophysical Research. 96 (E1): 15, 665–15, 674. Bibcode:1991JGR....9615665H. doi:10.1029/91JE01401.

- Howett, C. J. A.; Spencer, J. R.; Pearl, J.; Segura, M. (April 2010). "Thermal inertia and bolometric Bond albedo values for Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea and Iapetus as derived from Cassini/CIRS measurements". Icarus. 206 (2): 573–593. Bibcode:2010Icar..206..573H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.07.016.

- Hussmann, Hauke; Sohl, Frank; Spohn, Tilman (November 2006). "Subsurface oceans and deep interiors of medium-sized outer planet satellites and large trans-neptunian objects". Icarus. 185 (1): 258–273. Bibcode:2006Icar..185..258H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005.

- Jacobson, R.A. (2010). "Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters". SAT339 – JPL satellite ephemeris. JPL/NASA. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- Jaumann, R.; Clark, R. N.; Nimmo, F.; Hendrix, A. R.; Buratti, B. J.; Denk, T.; Moore, J. M.; Schenk, P. M.; Ostro, S. J.; Srama, Ralf (2009). "Icy Satellites: Geological Evolution and Surface Processes". Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. pp. 637–681. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_20. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9.

- Johnson, T. V.; Estrada, P. R. (2009). "Origin of the Saturn System". Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. pp. 55–74. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_3. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9.

- Khurana, K.; Russell, C.; Dougherty, M. (February 2008). "Magnetic portraits of Tethys and Rhea". Icarus. 193 (2): 465–474. Bibcode:2008Icar..193..465K. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.08.005.

- Lassell, W. (14 January 1848). "Observations of satellites of Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 8 (3): 42–43. Bibcode:1848MNRAS...8...42L. doi:10.1093/mnras/8.3.42. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- Matson, D. L.; Castillo-Rogez, J. C.; Schubert, G.; Sotin, C.; McKinnon, W. B. (2009). "The Thermal Evolution and Internal Structure of Saturn's Mid-Sized Icy Satellites". Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. pp. 577–612. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_18. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9.

- Moore, Jeffrey M.; Schenk, Paul M.; Bruesch, Lindsey S.; Asphaug, Erik; McKinnon, William B. (October 2004). "Large impact features on middle-sized icy satellites" (PDF). Icarus. 171 (2): 421–443. Bibcode:2004Icar..171..421M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.009.

- Muller, Daniel. "Pioneer 11 Full Mission Timeline". Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- Muller, Daniel. "Missions to Tethys". Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- "Voyager Mission Description". The Rings Node of NASA's Planetary Data System. 19 February 1997. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- Observatorio ARVAL (15 April 2007). "Classic Satellites of the Solar System". Observatorio ARVAL. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- Ostro, S.; West, R.; Janssen, M.; Lorenz, R.; Zebker, H.; Black, G.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Wye, L.; Lopes, R.; Wall, S. D.; Elachi, C.; Roth, L.; Hensley, S.; Kelleher, K.; Hamilton, G. A.; Gim, Y.; Anderson, Y. Z.; Boehmer, R. A.; Johnson, W. T. K. (August 2006). "Cassini RADAR observations of Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Iapetus, Hyperion, and Phoebe" (PDF). Icarus. 183 (2): 479–490. Bibcode:2006Icar..183..479O. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.02.019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016.

- Price, Fred William (2000). The Planet Observer's Handbook. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78981-3.

- Roatsch, T.; Jaumann, R.; Stephan, K.; Thomas, P. C. (2009). "Cartographic Mapping of the Icy Satellites Using ISS and VIMS Data". Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. pp. 763–781. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_24. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9.

- Schenk, P.; Hamilton, D. P.; Johnson, R. E.; McKinnon, W. B.; Paranicas, C.; Schmidt, J.; Showalter, M. R. (January 2011). "Plasma, plumes and rings: Saturn system dynamics as recorded in global color patterns on its midsize icy satellites". Icarus. 211 (1): 740–757. Bibcode:2011Icar..211..740S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.08.016.

- Seal, D. A.; Buffington, B. B. (2009). "The Cassini Extended Mission". Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. pp. 725–744. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_22. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9.

- Squyres, S. W.; Reynolds, Ray T.; Summers, Audrey L.; Shung, Felix (1988). "Accretional Heating of the Satellites of Saturn and Uranus". Journal of Geophysical Research. 93 (B8): 8779–8794. Bibcode:1988JGR....93.8779S. doi:10.1029/JB093iB08p08779. hdl:2060/19870013922.

- Stone, E. C.; Miner, E. D. (10 April 1981). "Voyager 1 Encounter with the Saturnian System" (PDF). Science. 212 (4491): 159–163. Bibcode:1981Sci...212..159S. doi:10.1126/science.212.4491.159. PMID 17783826.

- Stone, E. C.; Miner, E. D. (29 January 1982). "Voyager 2 Encounter with the Saturnian System" (PDF). Science. 215 (4532): 499–504. Bibcode:1982Sci...215..499S. doi:10.1126/science.215.4532.499. PMID 17771272. S2CID 33642529.

- Thomas, P. C.; Burns, J. A.; Helfenstein, P.; Squyres, S.; Veverka, J.; Porco, C.; Turtle, E. P.; McEwen, A.; Denk, T.; Giesef, B.; Roatschf, T.; Johnsong, T. V.; Jacobsong, R. A. (October 2007). "Shapes of the saturnian icy satellites and their significance" (PDF). Icarus. 190 (2): 573–584. Bibcode:2007Icar..190..573T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.012. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- Verbiscer, A.; French, R.; Showalter, M.; Helfenstein, P. (9 February 2007). "Enceladus: Cosmic Graffiti Artist Caught in the Act". Science. 315 (5813): 815. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..815V. doi:10.1126/science.1134681. PMID 17289992. S2CID 21932253. (supporting online material, table S1)

External links edit

- Tethys Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration Site

- Movie of Tethys's rotation by Calvin J. Hamilton (based on Voyager images)

- The Planetary Society: Tethys

- Cassini images of Tethys Archived 13 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Images of Tethys at JPL's Planetary Photojournal

- 3D shape model of Tethys (requires WebGL)

- Movie of Tethys' rotation from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Tethys global Archived 24 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine and polar Archived 24 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine basemaps (August 2010) from Cassini images

- Tethys atlas (August 2008) from Cassini images Archived 26 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Tethys nomenclature and Tethys map with feature names from the USGS planetary nomenclature page

- Google Tethys 3D, interactive map of the moon