Summary

The Adventures of Tintin: Breaking Free is an anarchist parody of the popular The Adventures of Tintin series of comics. An exercise in détournement, the book was written under the pseudonym "J. Daniels" and published by Attack International in April of 1988[1] and then republished in 1999. It has recently been re-printed by anarchist publishers Freedom Press which includes for the first time Tintin’s earlier adventures during the Wapping dispute as told in The Scum, a 1986 pamphlet which was produced in solidarity with the printworkers.

| Breaking Free | |

|---|---|

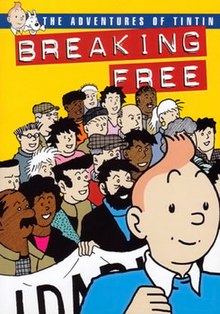

Cover of the January 1, 1999 Attack International paperback edition. | |

| Date | 1999 (paperback edition) |

| Main characters | Tintin and "the Captain" |

| Page count | 176 pages |

| Publisher | Attack International |

| Creative team | |

| Writers | J. Daniels (pseudonym) |

| Original publication | |

| Date of publication | 1988 |

| Language | English |

| ISBN | 0-9514261-0-9 |

The story features a number of characters based on those from the original series by Hergé, notably Tintin himself and Captain Haddock (referred to only as 'the Captain' and depicted here as being Tintin's uncle), but not the original themes or plot. Snowy is featured on the cover—being especially visible on the first edition's cover—but not in the narrative. The story tracks Tintin's development from a disaffected, shoplifting youth to a revolutionary leader.[2]

Plot summary edit

The comic opens with Tintin arriving at the Captain's flat in a fictional estate somewhere in England. Tintin has recently been sacked for losing his temper and punching his boss and expresses frustration about being "pushed around" and "kicked around like a lump of dogshit." The Captain offers to get Tintin a job on a local building site where he works. As the story progresses, Tintin meets the local residents and his workmates and issues faced by the area, such as racism, gentrification and general apathy from local government, are introduced.

The anger felt by the working-class people of this town boils over when a construction worker, Joe Hill (apparently named after the anarcho-syndicalist labour organiser of the same name) falls to his death due to poor safety standards at the local building site. Faced with insensitivity from their manager ("Had he been drinking?"), as well as apathy and condescension from their trade union official, the construction workers stage an unofficial, wildcat strike. The builders demand better safety standards, improved wages, a change of management for the site and a large sum of money for the family of their dead workmate.

The strike escalates, with management refusing to concede any of the demands, doing under the table deals with union officials to bring in strikebreakers. Meanwhile, the strike begins to spread to other local workplaces, becoming a symbol of class struggle, as well as a struggle for better short-term conditions. The workers become increasingly militant, turning to violent tactics and eventually firebombing the original building site. The strike begins to spread to other areas of the country without any official union involvement. Panicked, the UK government deals with strikers with increasing violence and repression, demonstrations turn into riots, and the Captain is arrested on false charges of conspiracy.

As the story closes, there is a demonstration of half a million people in the town in which the events of the book unfold, several people have brought rifles and references are made to "strike committees" taking power in other areas of the country, the army being sent into Liverpool to "restore order," and similar unrest taking place around the world. The last page features the Captain, Tintin and the Captain's wife Mary in silhouette. Tintin holds an assault rifle above his head, while the others raise their fists. Below is written: "This Is Not The End / Only the beginning…"

Reception edit

Its initial release in 1989 caused a furor in the tabloid newspapers in the United Kingdom, who excoriated the comic for characterizing Tintin as a "picket yob".[2] In a 1990 review, The Times called the book "a naive and brutish strip-cartoon book for junior Dave Sparts".[3] In 1994, The Guardian wrote: "The interesting things about it are the way each frame is adapted from Hergé's originals, and the touching belief in the possibility of an upsurge in grassroots socialist radicalism".[4] That same year, Martin Rowson, writing in The Independent, described the work as a "sad little publication" and called the book's approach to copyright "another acute observation in what I take to be a brilliant post-modern parody of a situationist canard produced during a sit-in at Hornsey School of Art circa 1972."[5] Gabriel Coxhead, writing in The Guardian in 2007, referred to the comic as "entertaining enough, if rather didactic", arguing that the "real interest is the artwork: each figure, every pose, has been assiduously copied from Hergé's own drawings, and recontextualised".[2] Zoheb Mashiur, writing in The Daily Star in 2021, wrote, "In the best traditions of Tintin stories, J Daniels took the character and placed him at the heart of contemporary issues. [...] He's not fighting for the perpetuation of a status quo, or inserting himself into the business of hapless foreigners; Daniels' Tintin is protecting his own people at home and trying to carve out a better world for them."[6]

Publication history edit

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Lezard, Nicholas (August 23, 1994). "Paperbacks: Round-up". The Guardian. Pg. T10

- ^ a b c Coxhead, Gabriel, "Gabriel Coxhead on loving homages and obscene pastiches of Hergé's Tintin", The Guardian, 2007-05-07.

- ^ Staff (January 28, 1990). "Diary; Books". The Times. Issue 8633.

- ^ Lezard, Nicholas (August 23, 1994). "Paperbacks: Round-up". The Guardian. Pg. T10

- ^ Rowson, Martin. (December 4, 1994). "Books for Christmas: Funny peculiar, I'd say; Humour". The Independent. Pg. 42

- ^ Mashiur, Zoheb (May 6, 2021). "An anarchist retelling of Tintin". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2021-06-20.

External links edit

- tintinrevolution.free.fr, online versions of the comic in French and English