Summary

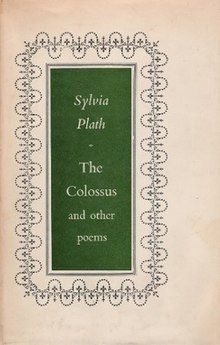

The Colossus and Other Poems is a poetry collection by American poet Sylvia Plath, first published by Heinemann, in 1960. It is the only volume of poetry by Plath that was published before her death in 1963.

Contents edit

The list below includes the poems in the US version of the collection, published by Heinemann in 1960.[1] This omits several poems from the first UK edition, published by Faber and Faber in 1967,[2] including five of the seven sections of "Poem for a Birthday", only two of which ("Flute Notes from a Reedy Pond" and "The Stones") are included in the US edition.

The title The Colossus comes from "Kolossus" a character who appeared in the ouija board games of Plath and Ted Hughes directing her to write poems on certain topics.[3][4]

- "The Manor Garden"

- "Two Views of a Cadaver Room"

- "Night Shift"

- "Sow"

- "The Eye-mote"

- "Hardcastle Crags"

- "Faun"

- "Departure"

- "The Colossus"

- "Lorelei"

- "Point Shirley"

- "The Bull of Bendylaw"

- "All the Dead Dears"

- "Aftermath"

- "The Thin People"

- "Suicide Off Egg Rock"

- "Mushrooms"

- "I Want, I Want"

- "Watercolor of Grantchester Meadows"

- "The Ghost's Leavetaking"

- "A Winter Ship"

- "Full Fathom Five"

- "Blue Moles"

- "Strumpet Song"

- "Man in Black"

- "Snakecharmer"

- "The Hermit at Outermost House"

- "The Disquieting Muses"

- "Medallion"

- "The Companionable Ills"

- "Moonrise"

- "Spinster"

- "Frog Autumn"

- "Mussel Hunter at Rock Harbor"

- "The Beekeeper's Daughter"

- "The Times Are Tidy"

- "The Burnt-out Spa"

- "Sculptor"

- "Flute Notes from a Reedy Pond"

- "The Stones"

Critical reception edit

Prominent journalist, poet and literary critic for The Observer newspaper, Al Alvarez, called the posthumous re-release of the book, after the success of Ariel, a "major literary event" and wrote of Plath's work:

"She steers clear of feminine charm, deliciousness, gentility, supersensitivity and the act of being a poetess. She simply writes good poetry. And she does so with a seriousness that demands only that she be judged equally seriously... There is an admirable no-nonsense air about this; the language is bare but vivid and precise, with a concentration that implies a good deal of disturbance with proportionately little fuss."[5]

Seamus Heaney said of The Colossus: "On every page, a poet is serving notice that she has earned her credentials and knows her trade."[6]

References edit

- ^ Sylvia, Plath (1960). The Colossus. London: Heinemann.

- ^ Sylvia, Plath (1967). The Colossus. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-09864-9.

- ^ Sylvia Plath 1438148445, 2013, (Journals, 409): In early July, they brought out their ouija board and spoke with their spirit, Pan, whose god is "Kolossus"; Pan told her to write about the Lorelei. 6 As a result, Plath wrote a poem, "Lorelei," which explored her Germanic roots.

- ^ Erica Wagner - Ariel's Gift: Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, and the Story of Birthday ... 2002 0393292673: ... she would be told that Prince Otto could not speak to her directly, because he was under orders from the Colossus. And when she pressed for an audience with the Colossus, they would say he was inaccessible. It is easy to see how her effort to come to terms with the meaning this Colossus held for her, in her poetry, became more and more central as the years passed.” Plath wrote to her mother in 1958 that “Pan claims his family god, 'Kolossus,' tells him much of this information.

- ^ Plath, Sylvia. The Colossus and Other Poems, Faber and Faber, 1967.

- ^ Seamus Heaney. "The Indefatigable Hoof-taps: Sylvia Plath." in The Government of the Tongue. NY: Faber, 1988, p. 154.

External links edit

- The Colossus and Other Poems at Faded Page (Canada)