Summary

The Fox and the Lion[1][2] is one of Aesop's Fables and represents a comedy of manners. It is number 10 in the Perry Index.[1]

The fables edit

The fable was briefly told in Classical Greek sources: 'A fox had never seen a lion before, so when she happened to meet the lion for the first time she all but died of fright. The second time she saw him, she was still afraid, but not as much as before. The third time, the fox was bold enough to go right up to the lion and speak to him.'

Since the story was not related in Latin until very late, it was not included in early European collections of Aesop's fables. Neo-Latin poems based on it were written by Hieronymus Osius and Gabriele Faerno in the 16th century, while in England it was included in Geoffrey Whitney's Choice of Emblemes (1586) and the collections of Francis Barlow and Roger L'Estrange in the late 17th century. Most of these followed the fable's original Greek source in giving it the moral that acquaintance overcomes fear. When it appeared in emblem books, however, it was as an illustration of how difficult things become easy with practice, but after its appearance in Samuel Croxall's The Fables of Aesop in 1722, the story was given a social interpretation. In his long commentary, Croxall remarks that the lesson to be learned from it is of ‘the two extremes in which we may fail, as to a proper behaviour towards our superiors’, namely bashfulness and ‘overbearing impudence’.[2] Although the proverb 'Familiarity breeds contempt' hardly fits the story as it stands, Jeffreys Taylor made it do so in a poem for children from his Aesop in Rhyme (1820).[3] In this the fox criticizes the lion's cold behaviour and is thrown by him into the river to teach him better manners.

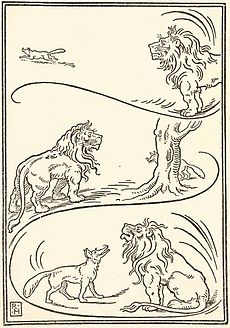

The tale with its three episodes does not present illustrators with many possibilities other than showing the two animals looking at each other and showing various emotional states. The possibilities of the Mediaeval convention of showing all the episodes in a composite design is made use of in the late 15th century Greek manuscript known as the Medici Aesop.[4] Thereafter one had to wait until the convention was revived towards the end of the 19th century. In 2011 the fable was set for narrator, horn and piano by American composer Anthony Plog.

Another fable with the same moral but a different outcome concerns the camel. Numbered 195 in the Perry Index,[5] it relates how people were terrified at their first sight of the camel. Once they understood its placid nature, however, they bridled it and allowed even their children to ride on it. This too had only ancient Greek sources and was rarely recorded in England except by L'Estrange and Townsend. Ivan Krylov wrote a variant of the fable with a donkey, who was initially a small animal, but asked Jupiter to make him a big beast, and scared everyone until they learned more about him, and now he is used for menial work.[6]

References edit

External links edit

- Illustrations from books from the 15-20th centuries