Summary

The Plague of the Zombies is a 1966 British horror film directed by John Gilling and starring André Morell, John Carson, Jacqueline Pearce, Brook Williams, and Michael Ripper. The film's imagery influenced many later films in the zombie genre.[citation needed]

| The Plague of the Zombies | |

|---|---|

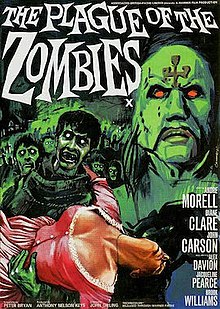

1966 theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Gilling |

| Written by | Peter Bryan |

| Produced by | Anthony Nelson Keys |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Arthur Grant |

| Edited by | Chris Barnes |

| Music by | James Bernard |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates | |

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £100,000 (approx)[3] |

| Box office | $2.345 million (rentals)[4] |

Plot edit

In a Cornish village in August 1860, the inhabitants of the town are dying from a mysterious plague that seems to be spreading at an accelerated rate. Even the local doctor, Peter Tompson, cannot combat the disease. Alarmed, Tompson sends for outside help from his friend and former mentor, Sir James Forbes. Accompanying Sir James is his daughter Sylvia, a childhood friend of Peter's wife, Alice. As Sir James and Sylvia arrive in the village, Sylvia deters a group of rowdy fox hunters from killing a fox. Shortly after, Sir James and Sylvia encounter a funeral procession in town, which is interrupted by the fox hunters, who come to harass Sylvia for intentionally misleading them. In the melee, the pallbearers drop the casket over the side of a bridge, revealing the corpse of John Martinus, a recently deceased man.

In an attempt to learn more about the disease, Sir James and Peter attempt to disinter the corpses that were recently buried, and are frightened upon finding the coffins empty. Meanwhile, Sylvia is harassed by the fox hunters while walking through the woods, and chased into a manor house owned by Squire Clive Hamilton. The hunters humiliate Sylvia in what appears to be pre-emptory rape, but are stopped by Squire Hamilton, who chastises them for harassing her. As Sylvia departs the house, she encounters a grey-skinned man near an abandoned tin mine headframe, and watches in horror as he throws Alice's lifeless body onto the ground. The following morning, Sylvia leads her father and Peter to the location, where they locate Alice's corpse.

Police accuse Tom, the brother of John Martinus, of killing Alice, as he was found sleeping in a drunken stupor near her body. Tom denies involvement, and claims he witnessed his deceased brother walking near the mine. An autopsy on Alice shows no signs of rigor mortis, and, even stranger, blood smeared on her face is determined to be of animal origin. Sir James notices a bandaged slash wound on her wrist, which Peter says she sustained on a piece of broken glass days before. Later that evening, Squire Hamilton pays Sylvia a visit. Purposely, Hamilton manages to shatter a wine glass, and Sylvia happens to cut her finger on one of the sharp edges of the glass. Secretly, the Squire conceals a piece of the blood-stained glass into his coat pocket and departs.

The next day, at Alice's funeral, Sylvia begins to feel faint. Through further investigation, Sir James and Peter learn that the squire lived in Haiti for several years and practised Haitian voodoo rituals, as well as black magic. Meanwhile, Squire Hamilton, now with a vestige of Sylvia's blood, has begun using his voodoo magic to lure Sylvia into the dark woods. She is led to the abandoned tin mine by an army of walking zombies for a voodoo ceremony that will transform her into one of the walking dead. It is revealed that Squire Hamilton has been turning the locals into the walking dead, in order to create workers to mine the tin and make money off of it.

While Peter follows Sylvia to the mines, Sir James investigates the Squire's house and finds some small figures in coffins the Squire uses for his voodoo. After a struggle with one of the Squire's henchmen the room is accidentally set ablaze, Sir James barely manages to escape after threatening a servant who notices the inferno for information on the mine. He races to the mines to join Peter, while in the mansion the figures in the coffins catch fire, causing their zombie counterparts to do the same and go crazy. Using the distraction caused by the burning crazed zombies, Sir James and Peter rescue Sylvia and flee from the burning flames as they listen to the anguished screams of Hamilton and his zombies; thus the plague is ended.

Themes edit

David Pirie compares it to The Reptile in that "[b]oth concern small Cornish communities threatened by a kind of alien and inexplicable plague which has been imported from the East via a corrupt aristocracy: both are, by implication at least, violently anti-colonial".

Scholar Ruth Heholt notes in an article in Hellebore magazine that both The Reptile and The Plague of the Zombies are part of a tradition that associates Cornwall with the exotic and the foreign. Cornwall represents "the non-English within England; the foreign at home."

Cast edit

- André Morell as Sir James Forbes

- Diane Clare as Sylvia Forbes

- Brook Williams as Dr. Peter Tompson

- Jacqueline Pearce as Alice Mary Tompson

- John Carson as Squire Clive Hamilton

- Alexander Davion as Denver (as Alex Davion)

- Michael Ripper as Sergeant Jack Swift

- Marcus Hammond as Tom Martinus

- Dennis Chinnery as Constable Christian

- Louis Mahoney as Coloured Servant

- Roy Royston as Vicar

- Ben Aris as John Martinus

- Tim Condren as Young blood

- Bernard Egan as Young blood

- Norman Mann as Young blood

- Francis Willey as Young blood

- Jerry Verno as Landlord

Production edit

Production on the film began on 28 July 1965 at Bray Studios. It was shot back-to-back with The Reptile using the same sets, a Cornish village created on the backlot by Bernard Robinson.[5] Pearce and Ripper appeared in both films.

The film was released in some markets on a double feature with Dracula: Prince of Darkness.[5]

Release edit

Box office edit

The film needed to earn $1.5 million in rentals to break even. It earned $2.34 million in rentals, thus making a profit.[4]

Critical reception edit

The Plague of the Zombies has been well received by critics. A contemporary review in Variety called it "a well-made horror programmer" with "formula scripting,"[6] and The Monthly Film Bulletin declared, "The best Hammer Horror for quite some time, with remarkably few of the lapses into crudity which are usually part and parcel of this company's work," adding, "Visually the film is splendid, with elegantly designed sets, and both interiors and exteriors shot in pleasantly muted colours; and the script manages quite a few offbeat strokes."[7]

Among more recent assessments, AllMovie called it a "spooky, atmospheric horror opus that ranks among Hammer Films' finest."[8] Time Out London wrote "perhaps a little tame these days, compared with modern gore-shock, but Gilling's Hammer chiller [...] is highly atmospheric."[9] The Hammer Story: The Authorised History of Hammer Films wrote, "much has been said of The Plague of the Zombies' influence on genre landmark Night of the Living Dead, made in 1968. A unique and shocking experiment in pushing the parameters of Hammer horror, The Plague of the Zombies deserves greater recognition in its own right."[10] Writing in The Zombie Movie Encyclopedia, academic Peter Dendle called it a "well-acted and capably-produced" zombie film that would go on to influence the depiction of zombies in many other films.[11] Radio Times gave the film four stars and called it "John Gilling's best work"

It currently holds an 83% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 12 reviews.[12]

Home media edit

Shout Factory released a Blu-ray of the film on 15 January 2019 with brand new commentaries from filmmakers Constantine Nasr, Ted Newsom and film historian Steve Haberman.[13]

In other media edit

A novelization of the film was written by John Burke as part of his 1967 book The Second Hammer Horror Film Omnibus.[14]

The film was adapted into a 13-page comic strip for the October 1977 issue of the magazine House of Hammer (volume 1, # 13, published by Top Sellers Limited). It was drawn by Trevor Goring and Brian Bolland from a script by Steve Moore. The cover of the issue featured a painting by Brian Lewis of a famous scene from the film.[15]

In the first season Amazing Stories television show episode "Mirror, Mirror", the cemetery scene film is used to portray a clip of Sam Waterston's character's horror film being shown by Dick Cavett.[citation needed]

References edit

- ^ "Amusements Guide". Evening Standard. 3 January 1966. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sunset Drive-In". The Chicago Tribune. 14 January 1966. p. 44 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Marcus Hearn & Alan Barnes, The Hammer Story: The Authorised History of Hammer Films, Titan Books, 2007 p 96

- ^ a b Silverman, Stephen M. (1988). The Fox That Got Away: The Last Days of the Zanuck Dynasty at Twentieth Century-Fox. L. Stuart. p. 325. ISBN 9780818404856.

- ^ a b "The Plague of the Zombies". Hammer Film Productions. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ "Film Reviews: The Plague of the Zombies". Variety: 6. 26 January 1966.

- ^ "The Plague of the Zombies". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 33 (385): 26. February 1966.

- ^ Binion, Cavett. "The Plague of the Zombies (1966) - Trailers, Reviews, Synopsis, Showtimes and Cast - AllMovie". AllMovie. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "The Plague of the Zombies Review. Movie Review - Film - Time Out London". Time Out London. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ Hearn & Barnes 2007, p. 101.

- ^ Dendle 2001, p. 133–136.

- ^ "The Plague of the Zombies - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Galgana, Michelle "Izzy" (31 December 2018). "Blu-ray Review: THE PLAGUE OF THE ZOMBIES Is Overlooked Hammer Fun". Screen Anarchy. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Jones 2000, p. 315.

- ^ "The House of Hammer #V2#1 (#13)". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

Sources edit

- Hearn, Marcus; Barnes, Alan (September 2007). "The Plague of the Zombies". The Hammer Story: The Authorised History of Hammer Films (Limited ed.). Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84576-185-1.

- Dendle, Peter (2001). The Zombie Movie Encyclopedia. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-9288-6.

- Jones, Stephen (2000). The Essential Monster Movie Guide: A Century of Creature Features on Film, TV, and Video. Billboard Books. ISBN 9780823079360.

External links edit

- The Plague of the Zombies at IMDb

- The Plague of the Zombies at AllMovie

- The Plague of the Zombies at the TCM Movie Database

- The Plague of the Zombies at the BFI's Screenonline