Summary

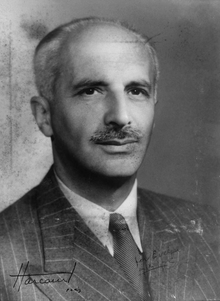

Theodore Deodatus Nathaniel Besterman (22 November 1904 – 10 November 1976) was a Polish-born British psychical researcher, bibliographer, biographer, and translator. In 1945 he became the first editor of the Journal of Documentation. From the 1950s he devoted himself to studies of the works of Voltaire.

Theodore Besterman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 November 1904 |

| Died | 10 November 1976 (aged 71) |

| Occupation(s) | Biographer, psychical researcher |

| Signature | |

Biography edit

Theodore Deodatus Nathaniel Besterman was born in 1904 in Łódź, Poland, but he relocated to London during his youth. In 1925 he was elected chairman of the British Federation of Youth Movements. During the 1930s Besterman lectured at the London School of Librarianship, and edited and published many works of, and about, bibliography.[1]

During World War II Besterman served in the British Royal Artillery and the Army Bureau of Current Affairs. Afterwards he worked for UNESCO, working on international methods of bibliography.[1]

During the 1950s Besterman began to concentrate on collecting, translating and publishing the writings of Voltaire, including much previously unpublished correspondence.[2] This was to occupy him for the rest of his life. He lived at Voltaire's house in Geneva, where he initiated the Institut et Musée Voltaire and published 107 volumes of Voltaire's letters and a series of books entitled "Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century".[1] The Forum for Modern Language Studies termed Besterman's edition of the correspondence "the greatest single piece of Voltairian scholarship for over a century.".[3]

During the final years of his life, Besterman negotiated with the University of Oxford, which culminated in his naming the university his residuary legatee and arranging for the posthumous transfer of his extensive collection of books and manuscripts, which included many collective editions, to an elegant room in the Taylor Institution (the university centre for modern languages), which has space for 9000 volumes. This was renamed the Voltaire Room. After Besterman’s death on 10 November 1976, the Voltaire Foundation was vested permanently in the University of Oxford.[4]

Besterman in 1969 published a detailed biography of Voltaire (541 pages + back matter), including many of Besterman's own translations of Voltaire's verse and correspondence.

He relocated back to Britain during the late 1960s, and died in Banbury in 1976.[1]

A humanist, in death, Besterman left a significant legacy to the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) to maintain the Voltaire Lecture for many years thereafter, exploring ‘any aspect of scientific or philosophical thought or human activity as affected by or with particular reference to humanism’. Humanists UK appoints a Voltaire Lecturer and awards them its prestigious Voltaire Medal each year.[5]

Besterman/McColvin Awards edit

During the 1990s the Library Association (LA) in the United Kingdom used to award a Besterman Award[6] every year for an outstanding bibliography. Now the LA's successor organisation, the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP), gives Besterman/McColvin Awards (often called the Besterman/McColvin Medals) for "outstanding works of electronic resources and e-books".[7]

Psychical research edit

Between 1927 and 1935 he was the investigating officer for the Society for Psychical Research (SPR). He wrote two books on Annie Besant and many works on psychical research.[1] He was a critical researcher, and became skeptical of most of the paranormal phenomena reported in the SPR journal.[8]

In 1929, Besterman with Ina Jephson and Samuel Soal performed a series of experiments to test for clairvoyance with controlled conditions.[9] The experiments involved the use of playing cards and sealed envelopes. The experiments were negative and did not reveal any evidence for clairvoyance.[9] In 1930 his criticism of Modern Psychic Mysteries, Millesimo Castle, Italy, a book on an Italian medium by Gwendolyn Kelley Hack, caused Arthur Conan Doyle to resign from the society. Doyle stated "... [The work of the Society] is an evil influence— is anti-spiritualist."[10][11]

Besterman is most well known for his 1932 paper that examined the relationship between eyewitness testimony and alleged paranormal phenomena. Besterman had a number of sitters attend a series of fake séances. He discovered that the sitters had failed to make accurate statements about the conditions and details of the séances and the phenomena that occurred. His study is often cited by skeptics to demonstrate that eyewitness testimony in relation to paranormal claims is unreliable.[12][13]

Besterman was skeptical of most physical mediums. In 1934, he visited Brazil to investigate the medium Carlos Mirabelli and detected trickery.[14]

Publications edit

Books edit

- A Bibliography of Annie Besant, London: The Theosophical Society in England, 1924

- Crystal Gazing: A Study in the History, Distribution, Theory and Practice of Scryng, London: William Rider & Son, 1924; reprinted: New York, University Books, 1965 (Library of the Mystic Arts: A Library of Ancient and Modern Classics)

- The Divining Rod: An Experimental and Psychological Investigation, London: Methuen & Co., 1926 (with William F. Barrett)

- In the Way of Heaven: Being the Teaching of Many Sacred Scriptures Concerning the Qualities Necessary for Progress on the Path of Attainment, London: Methuen & Co., 1927

- The Annie Besant Calendar, London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1927

- A Dictionary of Theosophy, London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1927

- Mind and Body: A Criticism of Psychophysical Parallelism, London: Methuen & Co., 1927 (translator)

- The Mind of Annie Besant, London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1927

- The Mystic Rose : A Study of Primitive Marriage and of Primitive Thought in its Bearing on Marriage, London: Methuen & Co., 1927 (editor)

- Some Modern Mediums, London: Methuen & Co., 1930

- Inquiry into the Unknown: A B.B.C. Symposium, London: Methuen & Co., 1934

- Mrs. Annie Besant: A Modern Prophet, London: Kegan Paul & Co., 1934

- Men Against Women: A Study of Sexual Relations, London: Methuen & Co., 1934

- On Dreams, London: Methuen & Co., 1935 (editor)

- The Beginnings of Systematic Bibliography, Oxford University Press, 1935; 2nd ed.: Burt Franklin, 1968 (Burt Franklin: Bibliography and Reference Series, 218)

- Water Divining: New Facts and Theories, London: Methuen & Co., 1938

- A World Bibliography of Bibliographies, Printed for the Author at the University Press, Oxford, 1939-1940; 4th ed.: A World Bibliography of Bibliographies and of Bibliographical Catalogues, Calendars, Abstracts, Digests, Indexes and the Like, Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1965-1966

- Voltaire's Notebooks, Geneva: Institut et Musée Voltaire, 1952, 2 vols

- Voltaire's Correspondence, Geneva: Institut et Musée Voltaire, 1953–65, 107 vols

- The Love Letters of Voltaire to his Niece, London: William Kimber, 1958 (editor and translator)

- Philosophical Dictionary, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1971 (translator)

- Collected Papers on the Paranormal, New York: Garrett Publications, 1967

- Voltaire, London: Longmans, 1969; New York: Harcourt Brace & World Inc., 1969

- A World Bibliography of African Bibliographies, Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1975

- A World Bibliography of Oriental Bibliographies, Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1975

- Theodore Besterman, Bibliographer and Editor: a Selection of Representative Texts, Francesco Cordasco, ed., Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1992 (The Great Bibliographers Series)

Papers edit

- — . (1926). The Folklore of Dowsing. Folklore 37 (2): 113-133.

- — . Rose, H. J. (1926). Folklore and Psychical Research Folklore 37 (4): 396-398.

- — . (1928). The Belief in Rebirth of the Druses and Other Syrian Sects. Folklore 39 (2): 133-148.

- — . (1928). Report of a Pseudo-Sitting for Physical Phenomena with Karl Kraus. Journal of Society for Psychical Research 24: 388-392.

- — . (1929). Report of a Four Months' Tour of Psychical Investigation. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 38: 409-480.

- — . (1930). Review: Modern Psychic Mysteries. Journal of Society for Psychical Research 26: 10-14.

- — . Jephson, Ina; Soal, Samuel. (1930). Report of a Series of Experiments in Clairvoyance. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 39: 375-414.

- — . (1930). The Belief in Rebirth Among the Natives of Africa (Including Madagascar). Folklore 41 (1): 43-94.

- — . (1932). An Experiment in Long-Distance Telepathy. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 27: 235-236.

- — . (1932). The Psychology of Testimony in Relation to Paraphysical Phenomena: Report of an Experiment. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 40: 363-387.

- — . (1932). The Mediumship of Rudi Schneider. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 40: 428-436.

- — . (1933). Note on an Attempt to Locate in Space the Alleged Direct Voice Observed in Sittings with Mrs. Leonard. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 28: 84-85.

- — . (1933). Report of an Inquiry into Precognitive Dreams. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 41: 186-204.

- — . (1933). "An Experiment in "Clairvoyance" with M. Stefan Ossowiecki. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 41: 345-351.

- — ; Gatty, Oliver. (1934). Report of an Investigation Into the Mediumship of Rudi Schneider. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 42: 251-285.

- — ; Gatty, Oliver. (1934). Further Tests of the Medium Rudi Schneider. Nature 134: 965-966.

- — . (1935). Reflections on the Mediumship of Rudi Schneider. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 29: 32-33.

- — . (1935). The Mediumship of Carlos Mirabelli. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 29: 141-153.

References edit

- ^ a b c d e Barber, Giles (2004). Besterman, Theodore Deodatus Nathaniel (1904–1976). Vol. Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Ayer, Alfred J (1986). "1". Voltaire. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-297-78880-5.

- ^ Brumfitt, J. H. (1965). "The present state of Voltaire studies". Forum for Modern Language Studies (3). Fmls.oxfordjournals.org: 230–239. doi:10.1093/fmls/I.3.230. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ Mason, Haydn. "A history of the Voltaire Foundation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Nichola Raihani explains the evolutionary origins of cooperation in the biggest Voltaire Lecture to date". Humanists UK. 23 September 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "The Library Association Medals", wiley.com, 1990. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Reference Award – Besterman/McColvin Award, cengage.com. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Wokler, Robert. (1998). The Subtextual Reincarnation of Voltaire and Rousseau. American Scholar 67 (2): 55-64.

- ^ a b Berger, Arthur S. (1988). Lives and Letters in American Parapsychology: A Biographical History, 1850-1987. McFarland & Company. p. 94. ISBN 0-89950-345-4

- ^ "Science: Houdini, Doyle". Online archive. Time magazine. 31 March 1930. Archived from the original on 27 December 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ^ Polidoro, Massimo. (2001). Final Seance: The Strange Friendship Between Houdini and Conan Doyle. Prometheus Books. p. 227. ISBN 1-57392-896-8

- ^ Wiseman, R., Smith, M and Wiseman, J. (1995). "Eyewitness Testimony and the Paranormal". Skeptical Inquirer, November/December, 29-32.

- ^ Wiseman, R., Greening, E., Smith, M. (2003). Belief in the Paranormal and Suggestion in the Seance Room. British Journal of Psychology 94: 285–297.

- ^ Anderson, Rodger. (2006). Psychics, Sensitives and Somnambules: A Biographical Dictionary with Bibliographies. McFarland & Company. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-7864-2770-3

External links edit

- Giles Barber, Theodore Besterman, November 2010

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Resignation. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 26: 45-52. (Including Besterman's reply).

- Voltaire Foundation