Summary

Titan Mare Explorer (TiME) is a proposed design for a lander for Saturn's moon Titan.[3] TiME is a relatively low-cost, outer-planet mission designed to measure the organic constituents on Titan and would have performed the first nautical exploration of an extraterrestrial sea, analyze its nature and, possibly, observe its shoreline. As a Discovery-class mission it was designed to be cost-capped at US$425 million, not counting launch vehicle funding.[4] It was proposed to NASA in 2009 by Proxemy Research as a scout-like pioneering mission, originally as part of NASA's Discovery Program.[6] The TiME mission design reached the finalist stage during that Discovery mission selection, but was not selected, and despite attempts in the U.S. Senate failed to get earmark funding in 2013.[7] A related Titan Submarine has also been proposed.[8][9]

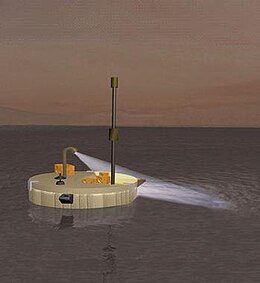

Artist's impression of TiME lake lander | |

| Mission type | Titan lander |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| Mission duration | 7.5 years Cruise: 7 years; 3–6 months at Titan[1] |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Dry mass | 700 kg ("representative value" landed mass) [2] |

| Power | 140 W |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 2016 (proposed)[3][4][5] Not taken beyond proposal |

| Rocket | Atlas V 411 |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-41 |

| Contractor | United Launch Alliance |

Discovery-class finalist edit

TiME was one of three Discovery Mission finalists that received US$3 million in May 2011 to develop a detailed concept study. The other two missions were InSight and Comet Hopper. After a review in mid-2012, NASA announced in August 2012 the selection of the InSight mission to Mars.[10]

Specifically, with launch specified prior to the end of 2025, TiME's arrival would have been in the mid-2030s, during northern winter. This means the seas, near Titan's north pole, are in darkness and direct-to-Earth communication is impossible.[11]

Missions to land in Titan's lakes or seas were also considered by the Solar System Decadal Survey. Additionally, the flagship Titan Saturn System Mission, which was proposed in 2009 for launch in the 2020s, included a short-lived battery-powered lake lander.[6][12] Opportunities for launch are transient; the next opportunity is in 2023–2024, the last chance in this generation.[13]

History edit

The discovery on July 22, 2006, of lakes and seas in Titan's northern hemisphere confirmed the hypothesis that liquid hydrocarbons exist on it.[14] In addition, previous observations of southern polar storms and new observations of storms in the equatorial region provide evidence of active methane-generating processes, possibly cryovolcanic features from the interior of Titan.[12]

Most of Titan goes centuries without seeing any rain, but precipitation is expected to be much more frequent at the poles.[1]

It is thought that Titan's methane cycle is analogous to Earth's hydrologic cycle, with meteorological working fluid existing as rain, clouds, rivers and lakes.[14] TiME would directly discern the methane cycle of Titan and help understand its similarities and differences to the hydrologic cycle on Earth.[1][12] If NASA had selected TiME, Ellen Stofan—a member of the Cassini radar team and the current Chief Scientist of NASA—would lead the mission as principal investigator, whereas the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) would manage the mission.[15] Lockheed Martin would build the TiME capsule, with scientific instruments provided by APL, Goddard Space Flight Center and Malin Space Science Systems.

Target edit

TiME's launch would have been with an Atlas V 411 rocket during 2016 and arriving to Titan in 2023. The target lake is Ligeia Mare (78°N, 250°W).[1] It is one of the largest lakes of Titan identified to date, with a surface area of about ~100,000 km2. The backup target is Kraken Mare.[3][12]

Science objectives edit

The Titan Mare Explorer would undergo a 7-year simple interplanetary cruise with no flyby science. Some science measurements would be made during entry and descent, but data transmissions would begin only after splashdown. The science objectives of the mission are:[3][12]

- Determine the chemistry of a Titan sea. Instruments: Mass Spectrometer (MS), Meteorology and Physical Properties Package (MP3).

- Determine the depth of a Titan sea. Instrument: Meteorology and Physical Properties Package (Sonar) (MP3).

- Constrain marine processes on Titan. Instrument: Meteorology and Physical Properties Package (MP3), Descent and surface cameras.

- Determine how the local meteorology over the sea varies on diurnal timescales. Instrument: Meteorology and Physical Properties Package (MP3), cameras.

- Characterize the atmosphere above the sea. Instrument: Meteorology and Physical Properties Package (MP3), cameras.

Malin Space Science Systems, which builds and operates camera systems for spacecraft, signed an early development contract with NASA to conduct preliminary design studies.[16] There would be two cameras. One would take pictures during the descent to the surface of Ligeia Mare, and the other would take pictures after landing.[16]

A Meteorology and Physical Properties Package (MP3) [17] would be built by the Applied Physics Laboratory. This instrument package would measure wind speed and direction, methane humidity, pressure and temperature above the 'waterline', and turbidity, sea temperature, speed of sound and dielectric properties below the surface. A sonar would measure the sea depth. Acoustic propagation simulations were performed and sonar transducers were tested at liquid-nitrogen temperatures to characterize their performance at Titan conditions.[18]

Power source edit

Titan's thick atmosphere and the weak sunlight at Titan's distance from the Sun rules out the use of solar panels.[19][20] Had it been selected by NASA, the TiME lander would have been the test flight of the Advanced Stirling Radioisotope Generator (ASRG),[6] which is a prototype meant to provide availability of long-lived power supplies for landed networks and other planetary missions. For this mission, it would be used in two environments: deep space and non-terrestrial atmosphere. The ASRG is a radioisotope power system using Stirling power conversion technology and is expected to generate 140–160 W of electrical power; that is four times more efficient than RTGs currently in use. Its mass is 28 kg and will have a nominal lifetime of 14 years.[3] Though it continues ASRG research,[21] NASA has since cancelled the Lockheed contract that would have readied an ASRG for a 2016 launch, and has decided to rely on existing MMRTG radioisotope power systems for long-range probes.[22][23]

- Specifications

- ≥14 year lifetime

- Nominal power: 140 W

- Mass ~ 28 kg

- System efficiency: ~ 30%

- Two GPHS 238

Pu

modules - Uses 0.8 kg plutonium-238

The capsule would not need propulsion: the wind and possible tidal currents are expected to push this buoyant craft around the sea for months.[5]

Communications edit

The vehicle would have communicated directly with Earth and, in principle, it could be possible to maintain intermittent contact for several years after arrival: Earth finally goes below the horizon as seen from Ligeia in 2026.[24] It will not have a line of sight to Earth to beam back more data until 2035.[25]

Surface conditions edit

Models suggested that waves on Ligeia Mare do not normally exceed 0.2 meters (0.66 ft) during the intended season of the TiME mission and occasionally might reach just over 0.5 meters (1.6 ft) in the course of a few months.[26] Simulations were performed to evaluate the capsule's response to the waves and possible beaching on the shore.[27] The capsule is expected to drift on the surface of the sea at 0.1 m/s, pushed by currents and wind with typical speeds of 0.5 m/s, and not exceeding 1.3 m/s (4.2 feet/second).[24] The probe would not be equipped with propulsion, and while its motion cannot be controlled, knowledge of its successive locations could be used to optimize scientific return, such as lake depth, temperature variations and shore imaging. Some proposed location techniques are measurement of Doppler shift, Sun height measurement, and Very Long Baseline Interferometry.[24]

Potential habitability edit

The chance to discover a form of life with a different biochemistry than Earth has led some researchers to consider Titan the most important world on which to search for extraterrestrial life.[28] A few scientists hypothesize that if the hydrocarbon chemistry on Titan crossed the threshold from inanimate matter to some form of life, it would be difficult to detect.[28] Moreover, because Titan is so cold, the amount of energy available for building complex biochemical structures is limited, and any water-based life would freeze without a heat source.[28] However, some scientists have suggested that hypothetical life forms may be able to exist in a methane-based solvent.[29][30] Ellen Stofan, TiME's Principal Investigator, thinks that life as we know it is not viable in Titan's seas, but stated that "there will be chemistry in the seas that may give us insight into how organic systems progress toward life."[31]

Similar mission concepts edit

- Although no lander mission is currently funded to explore the lakes of Titan, the scientific interest is growing.[32] A researcher at NASA has proposed that if TiME was to be launched, a logical follow-on mission would be a lake submersible called Titan Submarine.[8][9][32][33]

- A battery-powered lake lander was considered as an element of the Titan Saturn System Mission (TSSM) Flagship study, using a Saturn orbiter as a relay. A number of lake-lander variants were briefly considered in the 2010 NASA Planetary Science Decadal Survey.[34]

- A lake capsule was suggested in Europe in the 2012 EPSC meeting; it is called Titan Lake In-situ Sampling Propelled Explorer (TALISE).[35][36] The major difference would be a propulsion system, possibly using Archimedes screws to function in muddy as well as liquid environments. This effort was only a brief concept study, however.

Further reading edit

- Ralph Lorenz (2018). NASA/ESA/ASI Cassini-Huygens: 1997 onwards (Cassini orbiter, Huygens probe and future exploration concepts) (Owners' Workshop Manual). Haynes Manuals, UK. ISBN 978-1785211119.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d Yirka, Bob (March 23, 2012). "Probe mission to explore Titan's minuscule rainfall proposed". Physorg. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- ^ Seakeeping on Ligeia Mare: Dynamic Response of a Floating Capsule to Waves on the Hydrocarbon Seas of Saturn’s Moon Titan Ralph D. Lorenz and Jennifer L. Mann, Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 33, Number 2 (2015)

- ^ a b c d e Stofan, Ellen (2010). "TiME: Titan Mare Explorer" (PDF). Caltech. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Taylor, Kate (May 9, 2011). "NASA picks project shortlist for next Discovery mission". TG Daily. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2011.

- ^ a b Greenfieldboyce, Nell (September 16, 2009). "Exploring A Moon By Boat". National Public Radio (NPR). Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c Hsu, Jeremy (October 14, 2009). "Nuclear-Powered Robot Ship Could Sail Seas of Titan". Space.com. Imaginova Corp. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ "Discovery Mission Finalists Could Be Given Second Shot". Space News. July 26, 2013. Archived from the original on February 15, 2014. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (February 21, 2021). "Seven Hundred Leagues Beneath Titan's Methane Seas - Mars, Shmars; this voyager is looking forward to a submarine ride under the icebergs on Saturn's strange moon". The New York Times. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Oleson, Steven R.; Lorenz, Ralph D.; Paul, Michael V. (July 1, 2015). "Phase I Final Report: Titan Submarine". NASA. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Vastag, Brian (August 20, 2012). "NASA will send robot drill to Mars in 2016". Washington Post.

- ^ 1Dragonfly: A Rotorcraft Lander Concept for Scientific Exploration at Titan Archived December 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Ralph D. Lorenz, Elizabeth P. Turtle, Jason W. Barnes, Melissa G. Trainer, Douglas S. Adams, Kenneth E. Hibbard, Colin Z. Sheldon, Kris Zacny, Patrick N. Peplowski, David J. Lawrence, Michael A. Ravine, Timothy G. McGee, Kristin S. Sotzen, Shannon M. MacKenzie, Jack W. Langelaan, Sven Schmitz, Larry S. Wolfarth, and Peter D. Bedini. 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Stofan, Ellen (August 25, 2009). "Titan Mare Explorer (TiME): The First Exploration of an Extra-Terrestrial Sea" (PDF). Presentation to NASA's Decadal Survey. Space Policy Online. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 24, 2009. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- ^ Titan Mare Explorer: TiME for Titan. (PDF) Lunar and Planetary Institute (2012).

- ^ a b Stofan, Ellen; Elachi, C.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Lorenz, R. D.; Stiles, B.; Mitchell, K. L.; Ostro, S.; Soderblom, L.; et al. (January 4, 2007). "The lakes of Titan" (PDF). Nature. 445 (7123): 61–64. Bibcode:2007Natur.445...61S. doi:10.1038/nature05438. PMID 17203056. S2CID 4370622. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2018. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ Sutherland, Paul (November 1, 2009). "Let's go sailing on lakes of Titan!". Scientific American. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Kenney, Mary (May 19, 2011). "San Diego company may get deep space work". Sign On San Diego. Retrieved May 20, 2011.

- ^ Lorenz, Ralph; et al. (March 2012). "MP3 – A Meteorology and Physical Properties Package to explore Air-Sea interaction on Titan" (PDF). 43rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ Arvelo, Juan; Lorenz, Ralph D. (2013). "Plumbing the depths of Ligeia: Considerations for depth sounding in Titan's hydrocarbon seas". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 134 (6): 4335–4342. Bibcode:2013ASAJ..134.4335A. doi:10.1121/1.4824908. PMID 25669245.

- ^ "Why the Cassini Mission Cannot Use Solar Arrays" (PDF). NASA/JPL. December 6, 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Huygens Probe Sheds New Light on Titan. Charles Choi, Space.com. January 21, 2005. Quote: "Little sunlit penetrates the dense hydrocarbon atmosphere."

- ^ Sterling Research Laboratory / Thermal Energy Conversion

- ^ "The ASRG Cancellation in Context". Planetary.com. Planetary Society. December 9, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ^ Leone, Dan (January 16, 2014). "Lockheed Shrinking ASRG Team as Closeout Work Begins". SpaceNews.

- ^ Hadhazy, Adam (August 17, 2011). "Space Boat: A Nautical Mission to an Alien Sea". Popular Science. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- ^ Carlisle, Camille (March 14, 2012). "Smooth Sailing on Titan". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ Lorenz, Ralph D.; Mann, Jennifer (2015). "Seakeeping on Ligeia Mare: Dynamic Response of a Floating Capsule to Waves on the Hydrocarbon Seas of Saturn's Moon Titan" (PDF). APL Tech Digest. 33: 82–93. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c Bortman, Henry (March 19, 2010). "Life Without Water And The Habitable Zone". Astrobiology Magazine.

- ^ Strobel, Darrell F. (2010). "Molecular hydrogen in Titan's atmosphere: Implications of the measured tropospheric and thermospheric mole fractions". Icarus. 208 (2): 878–886. Bibcode:2010Icar..208..878S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.03.003.

- ^ McKay, C. P.; Smith, H. D. (2005). "Possibilities for methanogenic life in liquid methane on the surface of Titan". Icarus. 178 (1): 274–276. Bibcode:2005Icar..178..274M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.05.018.

- ^ "Happy Birthday Titan!". Space.com. March 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Oleson, Steven (June 4, 2014). "Titan Submarine: Exploring the Depths of Kraken". NASA – Glenn Research Center. NASA. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ David, Leonard (February 18, 2015). "NASA Space Submarine Could Explore Titan's Methane Seas". Space.com. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ Planetary Science Decadal Survey JPL Team X Titan Lake Probe Study Final report. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. April 2010.

- ^ Urdampilleta, I.; Prieto-Ballesteros, O.; Rebolo, R.; Sancho, J. (2012). TALISE: Titan Lake In-situ Sampling Propelled Explorer (PDF). European Planetary Science Congress 2012. Vol. 7 EPSC2012–64 2012. Europe: EPSC Abstracts.

- ^ Landau, Elizabeth (October 9, 2012). "Probe would set sail on a Saturn moon". CNN – Light Years. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2012.