Summary

Ulisse Aldrovandi (11 September 1522 – 4 May 1605) was an Italian naturalist, the moving force behind Bologna's botanical garden, one of the first in Europe. Carl Linnaeus and the comte de Buffon reckoned him the father of natural history studies. He is usually referred to, especially in older scientific literature in Latin, as Aldrovandus; his name in Italian is equally given as Aldroandi.[a]

Ulisse Aldrovandi | |

|---|---|

Painting of Ulisse Aldrovandi by Agostino Carracci. | |

| Born | 11 September 1522 |

| Died | 4 May 1605 (aged 82) Bologna, Papal States |

| Education | University of Bologna University of Padua |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural history |

| Institutions | University of Bologna |

| Notable students | Volcher Coiter |

Life edit

Aldrovandi was born in Bologna to Teseo Aldrovandi and his wife, a noble but poor family. His father was a lawyer, and Secretary to the Senate of Bologna, but died when Ulisse was seven years old. His widowed mother wanted him to become a jurist. Initially he was sent to apprentice with merchants as a scribe for a short time when he was 14 years old, but after studying mathematics, Latin, law, and philosophy, initially at the University of Bologna, and then at the University of Padua in 1545, he became a notary. His interests successively extended to philosophy and logic, which he combined with the study of medicine.[1]

In June 1549, Aldrovandi was accused and arrested for heresy on account of his espousing of the anti-trinitarian beliefs of the Anabaptist Camillo Renato. By September, he publicly abjured, but was nevertheless transferred to Rome, and remained in custody or house arrest until absolved in April, 1550. During this time, he befriended many local scholars. While in light captivity there, he became more and more interested in botany, zoology, and geology (he is credited for the invention/first written record of this word[2]). From 1551 onward, he organized a variety of expeditions to the Italian mountains, countryside, islands, and coasts to collect and catalogue plants.

He obtained a degree in medicine and philosophy in 1553 and started teaching logic and philosophy in 1554 at the University of Bologna. In 1559, he became professor of philosophy and in 1561 he became the first professor of natural sciences at Bologna (lectura philosophiae naturalis ordinaria de fossilibus, plantis et animalibus).[1] Aldrovandi was a friend of Francesco de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1574 – 1587), visiting his garden at Pratolino and travelling with him, compiling a list of the most valuable plants at Pratolino.[b] He also formed fruitful associations with botanical artists such as Jacopo Ligozzi, to further develop illustrated texts.[3] He died in Bologna on 4 May 1605, at the age of 82.

Aldrovandi's wife Francesca Fontana was invaluable to his research. He utilized her dowry to build their massive country estate that ultimately included his natural history collection. She was a research partner who located texts for him to cite and use in his books, edited his books, and wrote sections of them as well. She wrote the preface for his posthumous book On the Remains of Bloodless Animals, which Suzanne Le-May Sheffield described as "their shared work."[4]

Work edit

Over the course of his life, he would assemble one of the most spectacular cabinets of curiosities: his "theatre" illuminating natural history comprising some 7000 specimens of the diversità di cose naturali, of which he wrote a description in 1595. Between 1551 and 1554, he organized several expeditions to collect plants for a herbarium, among the first botanizing expeditions. Eventually, his herbarium contained about 4760 dried specimens on 4117 sheets in sixteen volumes, preserved at the University of Bologna. He also had various artists including Jacopo Ligozzi, Giovanni Neri, and Cornelio Schwindt, compose illustrations of specimens.

Botanic garden edit

At his demand and under his direction, a public botanic garden was created in Bologna in 1568, now the Orto Botanico dell'Università di Bologna.[5] Due to a dispute on the composition of a popular medicine with the pharmacists and doctors of Bologna in 1575, he was suspended from all public positions for five years. In 1577, he sought the aid of Pope Gregory XIII (a cousin of his mother), who wrote to the authorities of Bologna to reinstate Aldrovandi in his public offices and request financial aid to help him publish his books.

Collections edit

His vast collections in botany and zoology he willed to the Senate of Bologna; until 1742 the collections were conserved in the Palazzo Pubblico, then in the Palazzo Poggi, but were distributed among various libraries and institutions in the course of the nineteenth century. In 1907 a representative part were reunited at Palazzo Poggi, Bologna, where the 400th anniversary of his death was memorialized in a celebrative exhibition in 2005.

Neurofibromatosis edit

He was the first to have extensively documented the disease neurofibromatosis,[6] a type of skin tumour. Recently, however, it has been observed that in a work by Andrea Mantegna, this type of disease had been pictured 80 years earlier than in Androvandi's work.[7]

List of selected publications edit

Of the several hundred books and essays he wrote, only a handful were published during his lifetime:

- Antidotarii Bononiensis, siue de vsitata ratione componendorum, miscendorumque medicamentorum, epitome (1574)

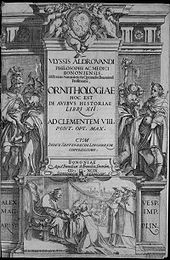

- Ornithologiae hoc est de avibus historiae libri XII (Bologna, 1599), another copy

- Ornithologiae tomus alter cum indice copiosissimo (Bologna, 1600)

- De animalibus insectis libri septem, cum singulorum iconibus ad vivum expressis (Bologna, 1602) 1618 edition

- Ornithologiae tomus tertius, ac postremus (Bologna, 1603) 1637 edition

- De reliquis animalibus exanguibus libri quatuor (Bologna, 1606)

- De piscibus libri V, et De cetis lib. vnus (Bologna, 1613)

- Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia (Bologna, 1621)

- Serpentum, et draconum (Bologna, 1640) (Natural History of Snakes and Dragons)

- Monstrorum historia cum Paralipomenis historiae omnium animalium (Bologna, 1642) 1658 edition from the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Musaeum metallicum in libros IV distributum Bartholomaeus Ambrosinus (Bologna, 1648)

- Dendrologiae naturalis scilicet arborum historiae libri duo sylua glandaria, acinosumq (Bologna, 1667)

- Observationes Variae Bologna, Biblioteca Universitaria, Ms. 136, XI folio 73

Honors edit

- The wrinkle ridge Dorsa Aldrovandi on the Moon is named after him.

- The Civico Orto Botanico "Ulisse Aldrovandi" in San Giovanni in Persiceto is named in his honor.

- The plant genus Aldrovanda is named after him.

Gallery edit

-

Cucurbita maxima Duchesne (c1660)

-

Basilisk from Serpentum, et draconum historiae libri duo (1640)

-

Harpy from Monstrorum Historia (1642)

-

Two headed lizard from Historia serpentum et draconum (1640)

-

Specimens of Nature

-

Owl

-

Blue-Headed Quail-Dove

-

Paduan Hen

-

Paduan Rooster

-

Turcicus Rooster

-

Blackbuck

-

Red Hartebeest and Blackbuck

-

Red Hartebeest and Mountain Coati

Notes edit

- ^ As in the title page of his Le antichita de la citta di Roma brevissimamente raccolte, 1556.

- ^ Observationes variae (Tomasi & Hirschauer 2002, footnote 52)

References edit

- ^ a b EB 1998.

- ^ Vai & Cavazza 2003.

- ^ Tomasi & Hirschauer 2002.

- ^ Le-May Sheffield, Suzanne (2006). Women and Science: Social Impact and Interaction. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 9.

- ^ Conan 2005, p. 96.

- ^ Ruggieri, M. (2003). "From Aldrovandi's "Homuncio" (1592) to Buffon's girl (1749) and the "Wart Man" of Tilesius (1793): Antique illustrations of mosaicism in neurofibromatosis?". Journal of Medical Genetics. 40 (3): 227–232. doi:10.1136/jmg.40.3.227. PMC 1735405. PMID 12624146.

- ^ Bianucci 2016.

Bibliography edit

- Bianucci, Raffaella; Perciaccante, Antonio; Appenzeller, Otto (October 2016). "Painting neurofibromatosis type 1 in the 15th century". The Lancet Neurology. 15 (11): 1123. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30210-1. PMID 27647642. S2CID 22047067.

- Castellani, Carlo (1970). "Ulisse Aldrovandi". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-0-684-10114-9.

- Conan, Michel, ed. (2005). Baroque garden cultures: emulation, sublimation, subversion. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 9780884023043. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- EB (20 July 1998). Ulisse Aldrovandi. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Findlen, Paula (1994). Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07334-0.

- Tomasi, Lucia Tongiorgi; Hirschauer, Gretchen A. (2002). The flowering of Florence: botanical art for the Medici. 3 March-27 May (PDF) (Exhibition catalogue). Washington: National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-85331-857-6.

- Tosi, Alessandro, ed. (1989). Ulisse Aldrovandi e la Toscana: carteggio e testimonianze documentarie. Firenze: L.S. Olschki. ISBN 9788822236821.

- Vai, Gian Battista; Cavazza, William (2003). Four centuries of the word geology: Ulisse Aldrovandi 1603 in Bologna. Minerva. ISBN 978-88-7381-056-8.

- Westfall, Richard S. (1995). "Aldrovandi, Ulisse". The Galileo Project. Rice University. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

External links edit

- Aldrovandi's Cats

- De Avibus Historiae (1666)

- AMS Historica – Ulisse Aldrovandi – University of Bologna

- Homepage of the Aldrovandi museum in Bologna

- Michon Scott, "Ulisse Aldrovandi"

- "Celebrazione per il IV centenario..." (in Italian)

- "Erbari essicati"

- Braque du Bourbonnais by Aldrovandi

- Ulisse Aldrovandi at arthistoricum.net

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Ulisse Aldrovandi in .jpg and .tiff format.

- "Ornithologiae ... libri XII" at the GDZ (Latin)

- Serpentum, et draconum historiae libri duo (1640) - digital facsimile from Linda Hall Library

- Musaeum Metallicum (1648) - digital facsimile from Linda Hall Library

- Ornithologiae (3 vols., 1599) - digital facsimiles from Linda Hall Library

- De quadrupedib.' digitatis viviparis libri tres... (1663) - digital facsimile from Linda Hall Library