Summary

Variant angina, also known as Prinzmetal angina, vasospastic angina, angina inversa, coronary vessel spasm, or coronary artery vasospasm,[2] is a syndrome typically consisting of angina (cardiac chest pain). Variant angina differs from stable angina in that it commonly occurs in individuals who are at rest or even asleep, whereas stable angina is generally triggered by exertion or intense exercise. Variant angina is caused by vasospasm, a narrowing of the coronary arteries due to contraction of the heart's smooth muscle tissue in the vessel walls.[3] In comparison, stable angina is caused by the permanent occlusion of these vessels by atherosclerosis, which is the buildup of fatty plaque and hardening of the arteries.[4]

| Variant angina | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Prinzmetal's angina, vasospastic angina[1] |

| |

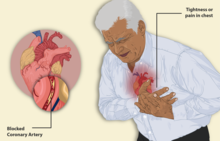

| Illustration depicting angina | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

Signs and symptoms edit

In contrast to those with angina secondary to atherosclerosis, people with variant angina are generally younger and have fewer risk factors for coronary artery disease with the exception of smoking, which is a common and significant risk factor for both types of angina. Affected people usually have repeated episodes of unexplained (e.g., in the absence of exertion and occurring at sleep or in the early morning hours) chest pain, tightness in throat, chest pressure, light-headedness, excessive sweating, and/or reduced exercise tolerance that, unlike atherosclerosis-related angina, typically does not progress to myocardial infarction (heart attack). Unlike cases of atherosclerosis-related stable angina, these symptoms are often unrelated to exertion and occur in night or early morning hours.[4] However, individuals with atherosclerosis-related unstable angina may similarly exhibit night to early morning hour symptoms that are unrelated to exertion.[5]

Cardiac examination of individuals with variant angina is usually normal in the absence of current symptoms.[2][6] Two-thirds of these individuals do have concurrent atherosclerosis of a major coronary artery, but this is often mild or not in proportion to the degree of their symptoms. Persons who have atherosclerosis-based occlusion that is ≥70% in a single coronary artery or that involves multiple coronary arteries are predisposed to develop a variant angina form that has a poorer prognosis than most other forms of this disorder.[7] In these individuals but also in a small percentage of individuals without appreciable atherosclerosis of their coronary arteries, attacks of coronary artery spasm can have far more serious presentations such as fainting, shock, and cardiac arrest. Typically, these presentations reflect the development of a heart attack and/or a potentially lethal heart arrhythmia; they require immediate medical intervention as well as consideration for the presence of, and specific treatment regimens for, their disorder.[8][9]

Variant angina should be suspected by a cardiologist when a) an individual's symptoms occur at rest or during sleep; b) an individual's symptoms occur in clusters; c) an individual with a history of angina does not develop angina during treadmill stress testing (variant angina is exercise tolerant); d) an individual with a history of angina shows no evidence of other forms of cardiac disease; and/or e) an individual without features of coronary artery atherosclerotic heart disease has a history of unexplained fainting.[4][8]

Complaints of chest pain should be immediately checked for an abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG). ECG changes compatible but not indicative of variant angina include elevations rather than depressions of the ST segment or an elevated ST segment plus a widening of the R wave to create a single, broad QRS complex peak termed the "monophasic curve".[4] Associated with these ECG changes, there may be small elevations in the blood levels of cardiac damage marker enzymes, especially during long attacks. Some individuals with otherwise typical variant angina may show depressions, rather than elevations in the ST segments of their ECGs during angina pain; they may also show new U waves on ECGs during angina attacks.[4]

A significant percentage of those with variant angina have symptom-free episodes of coronary artery spasm. These episodes may be far more frequent than expected, cause myocardial ischemia (i.e. insufficient blood flow to portions of the heart), and be accompanied by potentially serious abnormalities in the rhythm of heart beats, i.e. arrythmias. The only evidence of the presence of totally asymptomatic variant angina would be detection of diagnostic changes on fortuitously conducted ECGs.[4][9]

Risk factors edit

The intake of certain agents have been reported to trigger an attack of variant angina. These agents include:

- recreational agents (e.g. nicotine in tobacco and other forms, alcoholic beverages, marijuana, cocaine);

- catecholamine-like stimulants (e.g. epinephrine, dopamine, various amphetamines);

- the uterus-contracting drug, ergonovine;

- parasympathomimetic drugs (e.g. acetylcholine, methacholine);

- anti-migraine drugs (e.g. various triptans);

- chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g. 5-fluorouracil, capecitabine);

- high consumption of energy drinks have been associated with variant angina[citation needed].

- caffeine

In addition, hyperventilation and virtually any stressful emotional or physical (e.g. cold exposure) event that is suspected of causing significant rises in the blood levels of catecholamines may trigger variant angina.[4][7]

Mechanism edit

The mechanism that causes such intense vasospasm, as to cause a clinically significant narrowing of the coronary arteries is so far unknown, but there are three relevant hypotheses:

- Enhanced contractility of coronary vascular smooth muscle due to reduced nitric oxide bioavailability caused by a defect in the endothelial nitric oxide synthetase enzyme which leads to endothelial function abnormalities.[7][10][11]

- Acetylcholine is normally released by the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) at rest, and causes dilation of the coronary arteries.[12] While acetylcholine induces vasoconstriction of vascular smooth muscle cells through a direct mechanism, acetylcholine also stimulates endothelial cells to produce nitric oxide (NO). NO then diffuses out of the endothelial cells, stimulating relaxation of the nearby smooth muscle cells. In healthy arterial walls, the overall indirect relaxation induced by acetylcholine (via nitric oxide) is of greater effect than any contraction that is induced.

- When the endothelium is dysfunctional, stimulation with acetylcholine will fail to produce, or produce very little, nitric oxide. Thus, acetylcholine released by the PSNS at rest will simply cause contraction of the vascular smooth muscle.

- Thromboxane A2, serotonin, histamine, and endothelin are vasoconstrictor which activated platelets release and/or cause to be released. Abnormal platelet activation (e.g. by lipoprotein(a) interference with fibrinolysis by competing with plasminogen to thereby impair fibrinolysis and promote platelet activation) results in the release of these mediators and coronary vasospasm.[13][7][14]

- Increased alpha-adrenergic receptor activity in epicardial coronary arteries or the excessive release of the "flight or fight" catecholamines (e.g. norepinephrine) that activate these receptors may lead to coronary vasospasm.[4][7][15]

Other factors thought to be associated with the development of variant angina include: intrinsic hypercontractility of coronary artery smooth muscle; existence of significant atherosclerotic coronary artery disease; and reduced activity of the parasympathetic nervous system (which normally functions to dilate blood vessels).[6][7]

Diagnosis edit

Although variant angina has been documented in approximately 2% to 10% of angina patients, it can be overlooked by cardiologists who stop further evaluations after ruling out typical angina. Individuals who develop cardiac chest pain are generally treated empirically as an "acute coronary syndrome", and are immediately tested for elevations in their blood levels of enzymes such as creatine kinase isoenzymes or troponin that are markers for cardiac damage. They are also tested by ECG which may suggest variant angina if it shows elevations in the ST segment or an elevated ST segment plus a widening of the R wave during symptoms that are triggered by a provocative agent (e.g. ergonovine or acetylcholine). The electrocardiogram may show depressions rather than elevations in ST segments but in all diagnosable cases clinical symptoms should be promptly relieved and ECG changes should be promptly reversed by rapidly acting sublingual or intravenous nitroglycerin. However, the gold standard for diagnosing variant angina is to visualize coronary arteries by angiography before and after injection of a provocative agent such as ergonovine, methylergonovine or acetylcholine to precipitate an attack of vasospasm. A positive test to these inducing agents is defined as a ≥90% (some experts require lesser, e.g. ≥70%) constriction of involved arteries. Typically, these constrictions are fully reversed by rapidly acting nitroglycerin.[4][16]

Individuals with variant angina may have many undocumented episodes of symptom-free coronary artery spasm that are associated with poor blood flow to portions of the heart and subsequent irregular and potentially serious heart arrhythmias. Accordingly, individuals with variant angina should be intermittently evaluated for this using long-term ambulatory cardiac monitoring.[4][9]

Prevention edit

Numerous methods are recommended to avoid attacks of variant angina. Affected individuals should not smoke tobacco products. Smoke cessation significantly reduces the incidence of patient-reported variant angina attacks.[7] They should also avoid any trigger known to them to trigger these attacks such as emotional distress, hyperventilation, unnecessary exposure to cold, and early morning exertion. And, they should avoid any of the recreational and therapeutic drugs listed in the above signs and symptoms and risk factors sections as well as blockers of beta receptors such as propranolol which may theoretically worsen vasospasm by inhibiting beta-2 adrenergic receptor's vasodilation effect mediated by these receptors' naturally occurring stimulator i.e. epinephrine. In addition, aspirin should be used with caution and at low doses since at high doses it inhibits the production of the naturally occurring vasodilator, prostacyclin.[4][16]

Treatment edit

Acute attacks edit

During acute attacks, individuals typically respond well to fast-acting sublingual, intravenous, or spray nitroglycerin formulations. The onset of symptom relief in response to intravenous administration, which is used in more severe attacks of angina, occurs almost immediately while sublingual formulations of it act within 1–5 minutes. Spray formulations also require ~1–5 minutes to act.[17]

Maintenance edit

As maintenance therapy, sublingual nitroglycerin tablets can be taken 3-5 min before conducting activity that causes angina by the small percentage of patients who experience angina infrequently and only when doing such activity.[17] For most affected individuals, antianginals are used as maintenance therapy to avoid attacks of variant angina. Calcium channel blockers of the dihydropyridine class (e.g. nifedipine, amlodipine)[18] or non-dihydropyridine class (e.g. verapamil, diltiazem) are regarded as first-line drugs to avoid angina attacks. Long-acting nitroglycerins such as isosorbide dinitrate or intermittent use of short-acting nitroglycerin (to treat acute symptoms) may be added to the calcium channel blocker regimen in individuals responding sub-optimally to the channel blockers.

However, individuals commonly develop tolerance, or resistance, to the efficacy of continuously used long-acting nitroglycerin formulations. One strategy to avoid this is to schedule nitroglycerin-free periods of between 12 and 14 hours between doses of long-acting nitroglycerin formulations.[17] Individuals whose symptoms are poorly controlled by a calcium blocker may benefit from addition of a long-acting nitroglycerin and/or a second calcium channel blocker of a different class than the blocker already in use. Nevertheless, about 20% of individuals fail to respond adequately to the two-drug calcium blocker plus long-acting nitroglycerin regimen. If these individuals have significant permanent occlusion of their coronary arteries, they may benefit by stenting their occluded arteries. However, coronary stenting is contraindicated in drug-refractory individuals who do not have significant organic occlusion of their coronary arteries.[16]

For drug-refractory individuals without blockage, other, less fully investigated drugs may provide symptom relief. Statins, e.g. fluvastatin, while not evaluated in large-scale double-blind studies, are reportedly helpful in reducing variant angina attacks and should be considered in patients when calcium channel blockers and nitroglycerin fail to achieve good results.[4] There is also interest in using rho-kinase inhibitors, such as fasudil (available in Japan and China but not the USA),[16] and blocker of alpha-1 adrenergic receptors such as prazosin (which when activated cause vasodilation) but studies are needed to support their clinical utility in variant angina.[4][6]

Emergency edit

Individuals with certain severe complications of variant angina require immediate therapy. Individuals presenting with potentially lethal irregularities in the rhythm of their heart beating or a history of episodic fainting spells due to such arrhythmias require implantation of an internal defibrillator and/or cardiac pacemaker to stop such arrhythmias and restore normal heart beating.[8][9] Other rare but severe complications of variant angina, e. g. myocardial infarction, severe congestive heart failure, and cardiogenic shock require the same immediate medical interventions that are used for other causes of these extremis conditions. In all of these emergency cases, percutaneous coronary intervention to stent areas where coronary arteries evidence spasm is only useful in individuals who have concomitant coronary atherosclerosis on coronary angiogram.[4]

Prognosis edit

Most individuals with variant angina have a favorable prognosis provided they are maintained on calcium channel blockers and/or long-acting nitrates; five-year survival rates in this group are estimated as over 90%.[4][19] The Japanese Coronary Spasm Association established a clinical risk scoring system to predict outcomes for variant angina. Seven major factors (i.e. history of out of hospital cardiac arrest [score = 4]; smoking, angina at rest, physically obstructive coronary artery disease, and spasm in multiple coronary arteries [score = 2]; and presence of ST segment elevations on ECG and history of using beta blockers [score = 1]) where assigned the indicated scores. Individuals with scores of 0 to 2, 3 to 5, and ≥6 experienced an incidence of a major cardiovascular event in 2.5, 7.0, and 13.0% of cases.[20]

History edit

Dr. William Heberden is credited with being the first to describe in a 1768 publication the occurrence of chest pain attacks (i.e. angina pectoris) that appeared due to pathologically occluded coronary arteries. These attacks were triggered by exercise or other forms of exertion and relieved by rest and nitroglycerin. In 1959, Dr. Myron Prinzmetal described a type of angina that differed from the classic cases of Heberden angina in that it commonly occurred in the absence of exercise or exertion. Indeed, it often woke patients from their normal sleep. This variant angina differed from the classical angina described by Dr. Heberden in that it appeared due to episodic vasospasm of coronary arteries that were typically not occluded by pathological processes such as atherosclerosis, emboli, or spontaneous dissection (i.e. tears in the walls of coronary arteries).[4][19][13] Variant angina had been described twice in the 1930s by other authors[14][21] and was referred to as cardiac syndrome X (CSX) by Kemp in 1973, in reference to patients with exercise-induced angina who nonetheless had normal coronary angiograms.[22] CSX is now termed microvascular angina, i.e. angina caused by disease of the heart's small arteries.[4]

Some key features of variant angina are chest pain that is concurrently associated with elevations in the ST segment on electrocardiography recordings, that often occurs during the late evening or early morning hours in individuals who are at rest, doing non-strenuous activities, or asleep, and that is not associated with permanent occlusions of their coronary vessels. The disorder seems to occur more often in women than men, has a particularly high incidence in Japanese males as well as females, and affects individuals who may smoke tobacco products but exhibit few other cardiovascular risk factors.[4][23] However, individuals exhibiting angina symptoms that are associated with depressions in their electrocardiogram ST segments, that are triggered by exertion, and/or who have atherosclerotic coronary artery disease are still considered to have variant angina if their symptoms are caused by coronary artery spasms. Finally, rare cases may exhibit symptom-free coronary artery spasm that is nonetheless associated with cardiac muscle ischemia (i.e. restricted blood flow and poor oxygenation) along with concurrent ischemic electrocardiographic changes. The term vasospastic angina is sometimes used to include all of these atypical cases with the more typical cases of variant angina.[4] Here, variant angina is taken to include typical and atypical cases.

For a portion of patients, variant angina may be a manifestation of a more generalized episodic smooth muscle-contractile disorder such as migraine, Raynaud's phenomenon, or aspirin-induced asthma.[6] Variant angina is also the major complication of eosinophilic coronary periarteritis, an extremely rare disorder caused by extensive eosinophilic infiltration of the adventitia and periadventitia, i.e. the soft tissues, surrounding the coronary arteries.[24][25] Variant angina also differs from the Kounis syndrome (also termed allergic acute coronary syndrome) in which coronary artery constriction and symptoms are caused by allergic or strong immune reactions to a drug or other substance. Treatment of the Kounis syndrome very much differs from that for variant angina.[26]

See also edit

- Angina pectoris: the most common form of coronary artery spasm; it is due to atherosclerosis.

- Kounis syndrome: coronary artery spasm due to an allergic reaction.

- Eosinophilic coronary periarteritis: a very rare form of coronary artery spasm; it is due to non-allergic infiltration of coronary arteries by eosinophils.

References edit

- ^ "Variant Angina". www.escardio.org. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Prinzmetal's or Prinzmetal Angina, Variant Angina and Angina Inversa". American Heart Association. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Wu, Taixiang; Chen, Xiyang; Deng, Lei (24 November 2017). "Beta-blockers for unstable angina". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (11): CD007050. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007050.pub2. PMC 6486012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Ahmed B, Creager MA (April 2017). "Alternative causes of myocardial ischemia in women: An update on spontaneous coronary artery dissection, vasospastic angina and coronary microvascular dysfunction". Vascular Medicine (London, England). 22 (2): 146–160. doi:10.1177/1358863X16686410. PMID 28429664.

- ^ "What Is Angina?". National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Harrison's Cardiovascular Medicine 2/E (2 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education / Medical. 2013-08-02. ISBN 9780071814980.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harris JR, Hale GM, Dasari TW, Schwier NC (September 2016). "Pharmacotherapy of Vasospastic Angina". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 21 (5): 439–51. doi:10.1177/1074248416640161. PMID 27081186. S2CID 4087502.

- ^ a b c Nishizaki M (December 2017). "Life-threatening arrhythmias leading to syncope in patients with vasospastic angina". Journal of Arrhythmia. 33 (6): 553–561. doi:10.1016/j.joa.2017.04.006. PMC 5728714. PMID 29255500.

- ^ a b c d Kundu A, Vaze A, Sardar P, Nagy A, Aronow WS, Botkin NF (March 2018). "Variant Angina and Aborted Sudden Cardiac Death". Current Cardiology Reports. 20 (4): 26. doi:10.1007/s11886-018-0963-1. PMID 29520510. S2CID 3879012.

- ^ Yoo, Sang-Yong; Kim, Jang-Young (2009). "Recent Insights into the Mechanisms of Vasospastic Angina". Korean Circulation Journal. 39 (12): 505–11. doi:10.4070/kcj.2009.39.12.505. PMC 2801457. PMID 20049135.

- ^ Egashira, Kensuke; Katsuda, Yousuke; Mohri, Masahiro; Kuga, Takeshi; Tagawa, Tatuya; Shimokawa, Hiroaki; Takeshita, Akira (1996). "Basal release of endothelium-derived nitric oxide at site of spasm in patients with variant angina". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 27 (6): 1444–9. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(96)00021-6. PMID 8626956.

- ^ Sun, Hongtao; Mohri, Masahiro; Shimokawa, Hiroaki; Usui, Makoto; Urakami, Lemmy; Takeshita, Akira (28 February 2002). "Coronary microvascular spasm causes myocardial ischemia in patients with vasospastic angina". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 39 (5): 847–851. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01690-X. PMID 11869851.

- ^ a b Prinzmetal, Myron; Kennamer, Rexford; Merliss, Reuben; Wada, Takashi; Bor, Naci (1959). "Angina pectoris I. A variant form of angina pectoris". The American Journal of Medicine. 27 (3): 375–88. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(59)90003-8. PMID 14434946.

- ^ a b Parkinson, John; Bedford, D. Evan (1931). "Electrocardiographic Changes During Brief Attacks of Angina Pectoris". The Lancet. 217 (5601): 15–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)40634-3.

- ^ Yasue, Hirofumi; Touyama, Masato; Kato, Hirofumi; Tanaka, Satoru; Akiyama, Fumiya (February 1976). "Prinzmetal's variant form of angina as a manifestation of alpha-adrenergic receptor-mediated coronary artery spasm: Documentation by coronary arteriography". American Heart Journal. 91 (2): 148–155. doi:10.1016/s0002-8703(76)80568-6. PMID 813507.

- ^ a b c d Hung MJ, Cherng WJ (January 2013). "Coronary Vasospastic Angina: Current Understanding and the Role of Inflammation". Acta Cardiologica Sinica. 29 (1): 1–10. PMC 4804955. PMID 27122679.

- ^ a b c Thadani U (August 2014). "Challenges with nitrate therapy and nitrate tolerance: prevalence, prevention, and clinical relevance". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 14 (4): 287–301. doi:10.1007/s40256-014-0072-5. PMID 24664980. S2CID 207481645.

- ^ "NORVASC- amlodipine besylate tablet". DailyMed. 2019-03-14. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

Vasospastic Angina: NORVASC has been demonstrated to block constriction and restore blood flow in coronary arteries and arterioles in response to calcium, potassium epinephrine, serotonin, and thromboxane A2 analog in experimental animal models and in human coronary vessels in vitro. This inhibition of coronary spasm is responsible for the effectiveness of NORVASC in vasospastic (Prinzmetal's or variant) angina.

- ^ a b Swarup S, Grossman SA (2018). "Coronary Artery Vasospasm". PMID 29261899.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Takagi Y, Takahashi J, Yasuda S, Miyata S, Tsunoda R, Ogata Y, Seki A, Sumiyoshi T, Matsui M, Goto T, Tanabe Y, Sueda S, Sato T, Ogawa S, Kubo N, Momomura S, Ogawa H, Shimokawa H (September 2013). "Prognostic stratification of patients with vasospastic angina: a comprehensive clinical risk score developed by the Japanese Coronary Spasm Association". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 62 (13): 1144–53. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.018. PMID 23916938.

- ^ Brown, G.R.; Holman, Delavan V. (1933). "Electrocardiographic study during a paroxysm of angina pectoris". American Heart Journal. 9 (2): 259–64. doi:10.1016/S0002-8703(33)90720-6.

- ^ Kemp HG, Jr; Vokonas, PS; Cohn, PF; Gorlin, R (June 1973). "The anginal syndrome associated with normal coronary arteriograms. Report of a six year experience". The American Journal of Medicine. 54 (6): 735–42. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(73)90060-0. PMID 4196179.

- ^ Smolensky MH, Portaluppi F, Manfredini R, Hermida RC, Tiseo R, Sackett-Lundeen LL, Haus EL (June 2015). "Diurnal and twenty-four hour patterning of human diseases: cardiac, vascular, and respiratory diseases, conditions, and syndromes". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 21: 3–11. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2014.07.001. PMID 25129838.

- ^ Séguéla PE, Iriart X, Acar P, Montaudon M, Roudaut R, Thambo JB (April 2015). "Eosinophilic cardiac disease: Molecular, clinical and imaging aspects". Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases. 108 (4): 258–68. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2015.01.006. PMID 25858537.

- ^ Kajihara H, Tachiyama Y, Hirose T, Takada A, Takata A, Saito K, Murai T, Yasui W (2013). "Eosinophilic coronary periarteritis (vasospastic angina and sudden death), a new type of coronary arteritis: report of seven autopsy cases and a review of the literature". Virchows Archiv. 462 (2): 239–48. doi:10.1007/s00428-012-1351-7. PMID 23232800. S2CID 32619275.

- ^ Kounis NG (October 2016). "Kounis syndrome: an update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapeutic management". Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 54 (10): 1545–59. doi:10.1515/cclm-2016-0010. PMID 26966931. S2CID 11386405.

External links edit

- Crea, F; Lanza, GA (11 Nov 2003). "Vasospastic Angina". e-Journal of Cardiology Practice. 2 (9).