Summary

Wakaya[a] is a privately owned island in Fiji's Lomaiviti Archipelago. Situated at 17.65° South and 179.02° East, it covers an area of 8 square kilometres (3.1 sq mi). It is 18 kilometres (11 mi) to the east of Ovalau, the main island in the Lomaiviti Group. Two other islands close to Wakaya are Makogai to the north, and Batiki to the south-east.[4]

The islands of Wakaya (left) and Makogai (right) as seen from space | |||||||||||||||

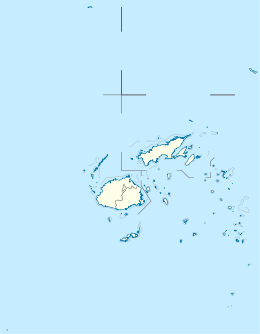

Wakaya Location in Fiji | |||||||||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates | 17°37′S 179°0′E / 17.617°S 179.000°E | ||||||||||||||

| Archipelago | Lomaiviti Islands | ||||||||||||||

| Adjacent to | Koro Sea | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 8 km2 (3.1 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Highest elevation | 181 m (594 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Administration | |||||||||||||||

| Division | Eastern Division | ||||||||||||||

| Province | Lomaiviti | ||||||||||||||

| District | Wakaya | ||||||||||||||

| Largest settlement | Wakaya Island Staff Village | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The coastal-marine ecosystem of the island contributes to its national significance as outlined in Fiji's Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan.[5] Since 1840, the island has been privately owned. In 1862, Wakaya became the site of the first attempt at commercial sugar production in Fiji. In the early 1940s, Wakaya was proposed as a new home for the Banabans. In 1973, Wakaya was purchased by businessman David Gilmour who also developed the island, building a resort, the Wakaya Club & Spa. In 2016, it was sold to the now-convicted Seagram's heiress Clare Bronfman who now owns most of the island.

Geography edit

The forested island of Wakaya is triangular in shape.[6][7] The western side of the island is fringed by a reef, and the rest is surrounded by a barrier reef enclosing a deep lagoon.[4] To the north is Davetanikaidraiba Passage; Wakaya is connected to the nearby island of Makogai by a narrow reef ridge.[4][7] The highest point of the island is in the north at the height of 181 metres (594 ft), where there are steep cliffs.[7][4] The southern part doesn't rise above 91.5 metres (300 ft) and is connected to the north by a comparatively low neck.[7]

Deer were introduced to the island from New Zealand decades prior to 2009, having been there by 1973.[8][9] As of 1973, there were also wild goats and pigs present.[9] Peregrine falcons make their nests on the cliffs of the island.[10] The invasive green iguanas, who had been accidentally introduced in the island of Qamea, have since spread to Wakaya and other islands.[11]

In 2016, Cyclone Winston caused damage to nearby coral reefs and significant damage to the vegetation on Wakaya.[12] Following the cyclone, a clam reintroduction and rehabilitation project was started in Wakaya and nearby Makogai later that year by the Ministry of Fisheries, as some species, such as the tevoro clam, had become locally extinct in Fiji due to being overharvested. Efforts were also being made by the ministry to conserve the endangered green turtle.[13]

History edit

Prehistory edit

Beginning around 300 BC, Wakaya Island was inhabited by Pacific Islanders.[citation needed] There were two fortified sites on the island named Delaini and Korolevu, with the radiocarbon date of 500–300 calibrated years before present.[14] Wakayan chiefs lived in Korolevu.[9] In 1873, Commodore James Graham Goodenough of the HMS Pearl investigated the site of a fort located on the highest point of the island, describing it as "a regular fort, with double ditch, nearly circular on top [...] the foundation of a temple (square) and a round foundation still stand".[15] In 1964 and around 1992 fieldwork of the forts on Wakaya was carried out.[15] As of 1994, pottery dating back four to five centuries prior had been found by archeologists.[9]

Recorded history edit

On 6 May 1789, Captain William Bligh sailed past Wakaya on a small boat with men loyal to him, after the mutiny on the Bounty on 28 April, describing the island as "a little larger one" in his logbook. Upon seeing two large druas (war canoes), they retreated as quickly as possible, aided by a squall.[9]

In 1837, roughly 800 warriors from the nearby island of Ovalau successfully attacked Wakaya. To avoid a gruesome death at the hands of the Ovalau warriors, the Wakayan chief jumped off a cliff on the western shore; that cliff edge is now called Chieftain's Leap in his honour.[9][16] In December 1840, the ship Currency Lass arrived in Levuka on Ovalau, and Houghton, the ship's owner, bought the island of Wakaya from the chief of Ovalau, the Tui Levuka.[17][18] The original inhabitants were removed in 1840, and since then, as of 1971, the island hadn't had more than a few plantation workers and their families living on it.[19]

In the early 1860s, 10 Vanuatu men, who were stranded by a sandalwood ship, worked on a plantation on Wakaya.[20] The first attempt at commercial sugar production in Fiji was by David Whippy on Wakaya Island in 1862, where he built a sugarcane mill, but this was a financial failure, as the island is small and not suited for growing sugarcane.[21][22][23] Whippy was an American sailor and trader who first arrived in Fiji in 1824, and spent the later years of his life on Wakaya until his death in 1871.[9][23] By 1870, the island was owned by the former American Consul in Fiji, Isaac Mills Brower, who had a homestead with livestock on Wakaya; cotton and coffee plantations were also present at the time. He left Fiji in 1876.[18][24] In 1877, the island was bought by Captain Frederick Lennox Langdale (1853–1913), a former Royal Navy officer, who later served on the Legislative Council of Fiji before being appointed governor's commissioner at Cakaudrove to the north, a position he resigned from around 1909.[25] Langdale had a Tudor-style house on the island by 1899; a few years after 1907, it was completely destroyed in a storm that also killed four Fijians.[7][26] In the late 1890s, Langdale also became the manager of the coconut plantations on Rabi Island, at the offer of Pacific Islands Company Ltd.[27]

On 21 September 1917, during World War I, German naval officer Felix von Luckner and his party were arrested at Wakaya by a group from the Fijian constabulary consisting of a British officer and four Indian soldiers. Previously that year, Luckner had been raiding Entente ships as the commander of the SMS Seeadler, but the ship wrecked on Mopelia island in French Polynesia during a storm, causing Luckner and five of his men to flee on a boat with the goal of capturing a vessel and returning for the rest of the crew. Armed with machine guns and rifles, and posing as Norwegians, they visited the Cook Islands and set off towards Fiji.[28][9][16]

In early 1920 the coconut estates on Wakaya and Naitaba suffered a heavy loss due to a storm.[29] On 11–12 January 1930 a tropical cyclone impacted the Fijian islands of Makogai, Wakaya and Gau, where it caused a moderate amount of damage.[30] In 1930, the roughly 7 month-long construction of the Wakaya lighthouse on the Wakaya reef was finished. The reef is located 4.8 kilometres (3 mi) from Wakaya island. The lighthouse is of reinforced concrete and has a height of 21.5 metres (70.5 ft) above the reef level.[31]

Banaban proposal edit

In the early 1940s, the Banabans proposed the acquisition of Wakaya as a new home for themselves, as their home island of Banaba was being exploited for phosphate by the British, thereby destroying it. At that time Wakaya was owned by Wakaya Ltd,[b] who agreed to sell it "if a reasonable offer was made". Colonial authorities surveyed the island, concluding it to be unsuitable for resettlement due to the soil being shallow and the water supply being poor. Levers Pacific Plantations Pty Ltd offered to sell Rabi Island in northern Fiji in October 1941. After a series of telegrams between the islanders and the British, in March 1942, the majority of Banabans agreed to a compromise where both Wakaya and Rabi were to be purchased. The Western Pacific High Commission couldn't agree on a price with the owners of Wakaya, so only Rabi Island was purchased in March with money from the Banaban Provident Fund.[32][27]

Purchase by David Gilmour and subsequent development edit

By 1969 the island was a coconut plantation,[c] and there were 10 labourers and their families living on the island.[19] Businessman David Gilmour saw the island from an airplane, and his hotel chain Southern Pacific Hotels Corporation shortly bought it in 1973 for $600,000. Since the island was uninhabited, Gilmour decided to repopulate Wakaya and build a resort on it.[9] Despite the purchase of the hotel chain by the Singaporean banker Tan Sri Khoo Teck Puat in 1981, the island of Wakaya remained separately owned by Gilmour and his business partners. Gilmour eventually bought the island for himself from two business partners in 1987.[10]

At least $13 million were spent on the development of the island,[9] which included the construction of a freshwater reservoir, an airstrip, a golf course, jetty, village, church, and a school.[33][34] Gilmour also developed the Wakaya Club & Spa, an exclusive resort opened in 1990[10] and built in the 1990s.[33][34][35] The resort has 10 luxury bures (bungalows), including the Governor's Bure and the Ambassador's Bure, which are grander than the rest.[8] It also houses a large private villa called Vale O (House in the Clouds), which was built in the 1990s.[33][34][35] As of 2002, the Wakaya Club resort had 60 full-time employees, 34 of whom were customer-facing, and all of whom were Fijian.[36] Starting in the early 1980s, Wakaya was managed by the married couple of Rob and Lynda Miller for 28 years.[37]

Change of ownership edit

Wakaya was devastated by Cyclone Winston in early 2016.[38][39][10] Later that year, the majority of Wakaya Island (80%) was sold to Seagram's heiress Clare Bronfman, who was convicted in 2019 of financing a human trafficking ring known as NXIVM. She was sentenced to 6 years and 9 months in September 2020.[40][41] As of 2018, the Resort Civil and Grounds Manager was Niumaia Niumataiwalu.[13] In 2022, the American tourism marketing company Pacific Storytelling partnered with the Wakaya Club & Spa resort.[42] In 2023, Monika Pal was appointed as the general manager of the resort, having previously been a manager since 2016.[43]

Demographics edit

The original inhabitants were removed in 1840, and the island became privately owned. Since then, as of 1971, the island hadn't had more than a few plantation workers and their families living on it.[19] For example, in the early 1860s, 10 Vanuatu men worked on a plantation on Wakaya,[20] and by 1969 the island was a coconut plantation, with 10 labourers and their families living on the island.[19] As of 2002, the Wakaya Club resort had 60 full-time employees, 34 of whom were customer-facing, and all of whom were Fijian.[36] The list of all polling venues for the 2018 Fijian general election recorded Wakaya Island Staff Village as having 161 voters, and the list for the 2022 general election had 87 voters in the village.[44][45]

Transport edit

There is a private aerodrome on the island operated by ACK Management PTE Ltd.[46] Its IATA airport code is KAY and its ICAO airport code is NFNW.[47][48] As of 1982, there was a 734 metres (2,408 ft) long airstrip.[49] The airline Air Wakaya had come into existence by 1991[50] and operated a 1992 Britten Norman Islander by 2002.[51] The airline began operating a Cessna 208 Caravan sometime during 2003–2005.[52] It now owns an 11-seat plane, the Cessna 208 Grand Caravan EX, which it acquired in 2013.[53][54] Flights are done from Nadi Airport to Wakaya.[51]

Notable people edit

Former owner David Gilmour and his wife Jill used to live on Wakaya Island four months a year.[33] Since the development of the Wakaya Club on the island, some famous people have stayed at the resort, including King Felipe VI of Spain (then a Prince) and his wife Letizia, Nicole Kidman and her husband Keith Urban, Bill Gates and his wife Melinda, Steve Jobs, Rupert Murdoch, George Lucas, Michelle Pfeiffer, David E. Kelley, Robert Zemeckis, Paris Hilton, Tom Cruise, and Keith Richards (who was hospitalised after falling from a coconut tree).[33][6][10][34]

In popular culture edit

Sections of the 1983 pirate adventure film Nate and Hayes (also known as Savage Islands) were filmed on Wakaya.[55]

Notes edit

- ^ Variously spelled in English during the first half of the 19th century, such as Vakkia, Ohokia, Volkkia, Vakia, and Wakaia.[3]

- ^ The executor of the late R.B.S. Watson's will owned most of the company's shares.[32]

- ^ The Estate Manager isn't named in the 1971 Robinson paper.[19] The Wakaya Club resort was later built on the site of a former coconut plantation.[10]

References edit

- ^ UNEP-WCMC. "Protected Area Profile for Wakaya Island from the World Database on Protected Areas". Protected Planet. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ "Fisheries (Wakaya Marine Reserve) Regulations 2015" (PDF). Government of Fiji Gazette. 20 February 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Geraghty, Paul (December 2020). "Maps and the European understanding of Fiji's toponymy 1643-1840". The Globe (88). Melbourne, Australia: 42–52. ISSN 0311-3930. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d Pub. 126 Sailing Directions (Enroute) Pacific Islands (12 ed.). Springfield, Virginia: National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. 2017. p. 89. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Ganilau, Bernadette Rounds (2007). Fiji Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (PDF). Convention on Biological Diversity. pp. 107–112. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ a b c "A Private Beach, a Princely Bure & You Beside Me" (PDF). Condé Nast Traveler. December 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Agassiz, Alexander (1899). The Islands and Coral Reefs of Fiji. Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 23–25. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ a b Boswell, Susie (26 February 2009). "A-list's Fiji secrets". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Schurman, Dewey (June 1994). "Fiji: A Tale of Two Islands". Islands Magazine. Vol. 14, no. 3. pp. 104–113. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Sandomir, Richard (30 June 2023). "David Gilmour, Who Brought Fiji's Water to the Masses, Dies at 91". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ Shah, Shipra; Dayal, Suchindra R.; Bhat, Jahangeer A.; Ravuiwasa, Kaliova (July–September 2020). "Green Iguanas: A Threat to Man and Wild in Fiji Islands?" (PDF). International Journal of Conservation Science. 11 (3): 765–782. ISSN 2067-533X. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ Mangubhai, Sangeeta (2016). "Impact of Tropical Cyclone Winston on Coral Reefs in the Vatu-i-Ra Seascape. Report No. 01/16" (PDF). Wildlife Conservation Society. Suva, Fiji. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ a b Katonivualiku, Mela (9 August 2018). "Fisheries spawn endangered giant clam species". Fiji Times. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Clark, Geoffrey; Anderson, Atholl (1 December 2009). "Site chronology and a review of radiocarbon dates from Fiji". The Early Prehistory of Fiji: 177. doi:10.22459/TA31.12.2009.07. ISBN 9781921666063. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ a b Best, Simon (1993). "At the Halls of the Mountain Kings. Fijian and Samoan Fortifications: Comparison and Analysis". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 102 (4): 389, 397, 400. ISSN 0032-4000. JSTOR 20706537. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ a b Stanley, David (1999). Fiji handbook. Moon. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-56691-139-9. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ United States Exploring Expedition: During the Year 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. C. Sherman. 1845. p. 361. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ a b Britton, Henry (1870). Fiji in 1870: Being the Letters of the Argus Special Correspondent, with a Complete Map and Gazetteer of the Fijian Archipelago. Samuel Mullen. pp. 53–54, 86.

- ^ a b c d e Robinson, D. E. (August 1971). "Observations on Fijian coral reefs and the crown of thorns starfish". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 1 (2): 99–112. Bibcode:1971JRSNZ...1...99R. doi:10.1080/03036758.1971.10419344. ISSN 0303-6758. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b Siegel, Jeff (1985). Plantation languages in Fiji (PDF) (PhD). Australian National University. p. 51. doi:10.25911/5d723a3cecb53. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ Moynagh, Michael (1981). Brown or white? a history of the Fiji sugar industry, 1973 - 1973 (PDF). Canberra: Australian National University. p. 13.

- ^ Ali, Rasheed A.; Narayan, Jai P. (1989). "The Fiji Sugar Industry: a brief history and overview of its structure and operations" (PDF). Pacific Economic Bulletin. 4 (2). Asia Pacific Press, Australian National University: 14. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ a b Melillo, Edward D. (1 July 2015). "Making Sea Cucumbers Out of Whales' Teeth: Nantucket Castaways and Encounters of Value in Nineteenth-Century Fiji". Environmental History. 20 (3): 449–474. doi:10.1093/envhis/emv049. ISSN 1084-5453. Retrieved 25 July 2023 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ "Brower, Isaac Mills (Dr), active 1850s-1870s". National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ "Personal". The Mercury. Hobart, Tasmania. 10 May 1913. p. 4. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ Newton, W. E. (19 March 1948). "Memories of Wakaya". Pacific islands monthly: PIM. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ a b Kempf, Wolfgang (2011). "Translocal Entwinements" (PDF). Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Göttingen. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ Gatty, Harold (1939). "A Historic Sextant". The International Hydrographic Review. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Damage at the islands". Taranaki Daily News. 10 March 1920. p. 5. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ Gabites, John Fletcher (17 May 1978). Information Sheet No. 28: Tropical Cyclones in Fiji: 1923 – 1939 (Report). Fiji Meteorological Service.

- ^ Great Britain Colonial Office (1931). Colonial Reports - Annual, Issues 1523-1547. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 35. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b McAdam, Jane (3 July 2014). "Historical Cross-Border Relocations in the Pacific: Lessons for Planned Relocations in the Context of Climate Change". The Journal of Pacific History. 49 (3): 301–327. doi:10.1080/00223344.2014.953317. S2CID 161154130. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Owens, Mitchell. "A Fantasy Home on a Tropical Island". Elle Decor. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Harrison (6 July 2023). "David Gilmour, entrepreneur who created Fiji water, dies at 91". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b Carruthers, Fiona (30 March 2017). "Lang Walker, Rich List property king, unveils his Kokomo Fiji resort". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

[...] and David Gilmour, a Canadian gold mine owner who in the 1990s built Wakaya Club & Spa and its pin-up villa Vale O, or the "house in the clouds".

- ^ a b Gibson, Dawn (2019). "More than Smiles – Employee Empowerment Facilitating High-Quality, Consistent Services – The Wakaya Club, Fiji" (PDF). The Journal of Pacific Studies. 39 (1). doi:10.33318/jpacs.2019.39(1)-01. S2CID 213541544. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ McComas, Sophie (5 April 2017). "Fiji's luxury Vatuvara Private Islands". Gourmet Traveller. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Cava, Litia (12 April 2016). "More Benefits For May, June". Fiji Sun. Suva, Fiji. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "David Gilmour obituary". The Times. 20 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "US heiress who owns Fiji resort is jailed". Radio New Zealand. 3 October 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Nxivm: Seagram heiress Clare Bronfman jailed in 'sex cult' case". BBC News. 30 September 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Tamanilo, Atama (23 June 2023). "New Representation For Iconic Fiji Resort Announced Wakaya Club & Spa Joins Pacific Storytelling Portfolio". Pacific Tourism Organisation. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "TOURIS Wakaya's First Female GM | Fiji Sun". PressReader. 15 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "The Provisional List of Polling Venues as at 31st December 2017" (PDF). Fijian Elections Office. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ "List of polling venues" (PDF). Fijian Elections Office. 7 November 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ "2021 Annual Report" (PDF). Civil Aviation Authority of Fiji. 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Global airport codes" (PDF). Emirates SkyCargo. p. 27. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Location Indicators by State" (PDF). SKYbrary. 17 September 2010. p. 42. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ "Country profiles - Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, Western Samoa". Pacific Islands Development Program. October 1982. p. 20.

- ^ Winchester, Simon (1991). Pacific Rising: The Emergence of a New World Culture. Prentice-Hall Press. pp. 404–405. ISBN 978-0-13-807793-8. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ a b Hone, Lucy (2002). "The Wakaya Club". The Good Honeymoon Guide. pp. 62–63.

- ^ "60 Years of Flying Career in Aviation" (PDF). Aviation Safety Bulletin (2). Civil Aviation Authority of Fiji: 8. April 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ Lal, Rachna (26 July 2013). "Wakaya Group brings new luxury aircraft". Fiji Sun. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ Kumar, Ashna (4 August 2018). "Briefly". Fiji Sun. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ "Nate and Hayes". AFI Catalog. Retrieved 22 July 2023.