Summary

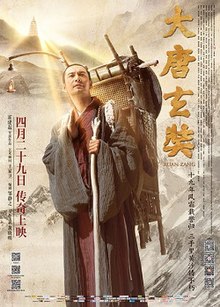

Xuanzang or Xuan Zang is a 2016 Chinese-Indian historical adventure film that dramatizes the life of Xuanzang (602—664), a Buddhist monk and scholar.[5] The film depicts his arduous nearly two-decade overland journey to India during the Tang dynasty on a mission to bring Buddhist scriptures to China. The film is directed by Huo Jianqi and produced by Wong Kar-wai. It stars Huang Xiaoming as Xuanzang, and includes cameo or short performances by other accomplished actors including Kent Tong, Purba Rgyal, Sonu Sood and Tan Kai.[1] It was released in China on 29 April 2016, with distribution in China by China Film Group Corporation.[3] It was selected as the Chinese entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 89th Academy Awards but was not nominated.[6] It won the Golden Angel Award Film and the best screenwriter categories at the 12th Chinese American Film Festival[7] and was nominated in several categories at the 31st Golden Rooster Awards.[8]

| Xuanzang | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 大唐玄奘 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 大唐玄奘 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Directed by | Huo Jianqi[1] | ||||||

| Written by | Zou Jingzhi[1] | ||||||

| Produced by | Wong Kar-wai[1] | ||||||

| Starring | Huang Xiaoming[1] | ||||||

| Cinematography | Sun Ming[1] | ||||||

| Music by | Wang Xiaofeng[1] | ||||||

Production companies | |||||||

| Distributed by | China Film Group Corporation[3] | ||||||

Release date |

| ||||||

Running time | 118 minutes [1] | ||||||

| Countries | China and India[1] | ||||||

| Languages | Mandarin and some Sanskrit[4] | ||||||

| Box office | CN¥32.9 million[3] | ||||||

Plot edit

During the Tang dynasty's era of "Zhen Guan" (of Emperor Taizong), Xuan Zang, a young Buddhist monk, in his quest to find the essence of Buddhism, embarks on a journey to India, that is fraught with perils and dangers. He encounters natural disasters, and sees the sufferings of the common people. Soldiers get in his way, his disciple betrays him, he struggles through deserts, is short on food and water, and traverses treacherous snow-covered mountain ranges. He finally arrives in India, and studies Buddhism in earnest.[1] By the time he returns to China, he is a little over 40 years old and he then devotes the remainder of his life to translating and studying the Sanskrit scriptures that he carried back from India.[5]

The screen play is largely based on a biography by Sramana Huili, a Tang dynasty Buddhist priest.[1] Xuanzang's works and his biography were also inspiration for the Classic Ming dynasty novel Journey to the West purportedly by Wu Ch'eng-en, and translated by Arthur Waley in his allegorical book Monkey, published by Allen and Unwin Ltd in 1942. This later fanciful folktale primarily deals with the exploits of Sun Wu Kong (“the Monkey King”), who is Xuanzang's protector. According to the film credits the real-life Xuanzang may have traveled 25,000 kilometers during his 19-year journey and visited 110 countries.

Xuanzang’s life depicted in the film and the novel Journey to the West share an overall theme, i.e.: his quest to bring Buddhist Scriptures to Tang dynasty China. In addition, there are subtle parallels, for example, in order to start his journey Xuanzang must get past 5 watchtowers where there are warrants for his arrest. As noted in the Chasing Dramas: all things Chinese drama website (which has a detailed summary of the plot), “the 5 watchtowers are changed to the 5 mountain peaks or 五行山 which represent the hand of the Ru Lai Buddha. The Monkey King 孙悟空 wreaked havoc and tried to escape the heavens but the [Buddha] used his hands to create five mountain peaks that the Monkey King could not escape. The monkey king was imprisoned under the mountain until he was rescued by his teacher, Xuan Zang."[9]

In another example, in the film Xuanzang nearly dies of thirst in the desert but is rescued by his old wise horse. In the novel, “Xuan Zang has a trusty steed the White Dragon Horse or 白龙马. The White Dragon Horse was actually a dragon prince who serves as Xuan Zang’s steed for his journey.”[9]

Cast edit

The story of Xuanzang’s epic quest is shown as a series of encounters with characters portrayed in cameo performances listed in part below in order of appearance.[1][9] The film periodically includes maps to show his progress to the locations where the encounters occur.

- Jonathan Kos-Read as Alexander Cunningham, British archaeologist active during India’s colonial period who attests to the accuracy of Xuanzang’s accounts of India in an introduction.

- Huang Xiaoming as Xuanzang, the protagonist and only character seen throughout the duration of the film.

- Zhao Liang as imperial edict reader, who announced that, because of a famine, the citizens of Chang’an may leave. According to the film’s text insert, this allows Xuanzang to join the exodus in 627.

- Xu Zheng as Li Daliang, the governor of Liangzhou who ordered Xuanzang to return to Chang’an.

- Karim Hajee as Haihui, the senior Buddhist priest in the region of Hexi who helped Xuanzang. He sent two acolytes to accompany Xuanzang for a while.

- Luo Jin as Li Chang, sympathetic prefect of Guazhou who tore up a warrant for Xuanzang’s arrest.

- Vivian Dawson as Wu Qing, Silk Road merchant, leading a caravan though the desert which Xuanzang joins for a while.

- Lou Jiayue as a woman from the western region who joins Xuanzang for a while and whose father gives Xuanzang an old horse who knows the way.

- Purba Rgyal as Shi Putuo, aka Vandak, a disciple who approaches chanting Xuanzang with a knife with an intent to kill him. In the end, he does not do it but is sent away.

- Tan Kai as Wang Xiang, watchtower captain, whose men shoot arrows at Xuanzang but who sends him on his way after learning of his mission.

- Che Xiao as Xuanzang's mother (flashback). Xuanzang has a vision of his mother while hallucinating in the Taklamakan Desert after spilling his water. He is saved by his old horse which carries him unconscious to Wild Horse Spring and then to Gaochang.

- Jiang Chao as King Aratürük, whom Xuanzang meets in Yi Wu, today’s Hami, after traversing the desert at the end of 629. He asks Xuanzang to visit the neighboring kingdom of Gaochang (Karakhajo). Xuanzang complies despite reservations.

- Andrew Lin as Qu Wentai, king of Gaochang, who tried to force Xuanzang to remain with him, which caused Xuanzang to begin a hunger strike. The king relents and sends escorts to accompany Xuanzang across the treacherous snow-covered mountain peaks of Lingshan (in Tian Shan mountain ranges).

- Gao Xing as Gaochang queen.

- Kent Tong as Mucha Judou, perhaps the King of Kucha, who along with the virtuous monk, Moksha Gupta, greeted Xuanzang ceremoniously with beautiful music and dancing. Xuanzang waited at the capital for better weather before crossing the mountains and then continuing his travels to India.

- Ram Gopal Bajaj as Śīlabhadra, the Right Dharma Store at Nalanda Temple in India which Xuanzang reached in Aug 631. Xuanzang kissed his feet and asked to become his student.

- Ali Fazal as Jayaram, a slave who was cursed by his master for touching his daughter while rescuing her from a fire. Jayaram was able to save some of the scriptures when Xuanzang’s boat capsized and was eventually freed of his curse with Xuanzang’s help.

- Neha Sharma as Kumari, Jayaram’s wife, who was cast out by her father.

- Sonu Sood as Emperor Harshavardhana who invites Śīlabhadra, of Nalanda Temple to send representatives to a Great Debate on the merits of Mahayana and Hinayana Buddhism. Xuanzang was chosen as the chief defender of Mahayana Buddhism. Emperor Harsha declared him the winner.

- Mandana Karimi as Rajyashri, Emperor Harsha’s sister.

- Winston Chao as Emperor Taizong of Tang, who welcomed Xuanzang back to Tang China in 642 where Xuanzang wrote translations of the scriptures that he had brought back with him. Emperor Taizong wrote the preface.

Soundtrack edit

Production edit

The film was produced by China’s biggest state owned production company China Film Corporation and its Indian partner Eros International. It was a prestige project as the first agreement on joint productions was signed in the presence of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping in May 2015.[4][11]

It was filmed on location in Turpan (including the Flaming Mountain Scenic Area), Changji, Altay, Aksu, Kashi all of which are in the Xinjiang province of China, the Gansu province of China, and India.[12][9] The sets were lavish, hundreds of extras were used and 10 companies from the US and China comprising 200 people were hired for post-production.[11]

In an interview with the Hindustan Times, translated from Chinese, the director noted that most of the shoots were outdoors. “It was physically taxing. In India, we spent 10 days in April and May and another 20 days in September. . . The heat and the sun were all very challenging.”[11]

The primary language spoken in the film is Mandarin. However, an important dialog between Xuanzang and his master, Śīlabhadra, is in Sanskrit, a rare instance of the use of this language in a mainstream film. The director noted that "We spent a long time with Sanskrit scholars, both in India and Peking University, to get this right, and we had Huang Xiaoming do the lines himself”.[4]

Consistency with Historical Biography edit

The film is based on a script by Xue Keqiao and Mu Jun which in turn is based on a biography by a Tang Buddhist monk, Sramana Huili.[1] The manuscript of Huili’s biography was scattered after his death but was recompiled by another monk, Shi Yancong.[13]

The film credits list many advisors and venerable priests,[1] nevertheless, liberties were taken for dramatic effect. For example, the film begins with a scene of baby Xuanzang being placed in a basket and floated down river where he is rescued by a monk who teaches him Buddhist scriptures. However, his biography indicates that he was raised at home and taught the scriptures by his father and older brother.[14] The fictitious account in the film appears in the Ming dynasty novel Journey to the West.[9]

In the film, as Vandak, the fallen disciple, departs, he advises Xuan Zang to find an old horse who knows the way. Xuanzang meets a “woman from the western region” (per film credits) who accompanies him in the desert and her father later gives him the horse.[1] In the biography, Xuanzang had bought a new horse. Before setting out across the desert, he meets Bandha (Vandak) who is accompanied by an old man riding a skinny roan horse. Xuanzang remembers a prophecy about his journey on an old horse. The old man’s horse and his saddle match the prophecy exactly; so, he trades his sturdy horse for the skinny one, which later saves his life.[15]

In the film, men (and their horses) escorting Xuanzang across the Lingshan mountains are caught in an avalanche. In the biography, he lost about 1/3rd of his men and many oxen and horses, but the deaths were caused by cold and hunger, not an avalanche.[16]

In the film, Xuanzang sets out across a river in a boat loaded with an elephant and his scriptures. A sudden storm capsizes the boat, and all including Xuanzang, the scriptures and elephant fall into the river. The slave, Jayaram, dives underwater to rescue some of the scriptures.[9] In the biography, the boat is tossed by the waves but does not overturn. The unnamed guardian of the scriptures falls overboard. He is saved by the other passengers, but the scriptures are lost. Xuanzang was wading across the river on the elephant, and they were not on board.[17][18]

Reception edit

The film grossed US$2.94 million on its opening weekend in China.[19] It received mixed reviews there. According to a review in the India Today: “As of May 3, [2016] Xuanzang was a lowly seventh at the box office, despite heavy government promotion, earning less than a tenth of a top-grossing Chinese romantic comedy that released on the same day.” It was criticized for a thin storyline consisting primarily of random occurrences during his journey.[4]

On the other hand, websites catering to those more interested in Chinese drama and history had more positive responses. For example, a review by Derek Elley on the Sino-Cinema website commented that “most of Xuanzang’s encounters are quite engrossing, thanks to the casting” and he goes on to praise several of the actors. He further commented that: “Given the need to have a star in the title role, and one who can project a strong sense of conviction, Huang is an excellent choice, all firm jaw and intense gaze. Though he doesn’t get much chance to build a personality for Xuanzang outside his Buddhist platitudes, Huang does manage to carry the film on his shoulders . . .” The photography is referred to as “stunning”.[1] The Chasing Dramas: All Things Chinese Dramas website summed up a lengthy review with a comment that It was a thoroughly enjoyable watch and it appeared to stay pretty true to history "– so if you want to spend 2 hours watching the gorgeous landscape and learn about history, this is the movie for you."[9]

During an interview by India Today, the director, Huo Jianqi, insisted that Xuanzang was worth the effort, and has praised both governments for backing what he says is a long-overdue venture. "This wasn't about making money," he said, "this was about telling the real story of someone who changed our history, not a magical story that could have sold well at the box office."[4]

Awards and nominations edit

- 12th Chinese American Film Festival[7]

- Golden Angel Award Film

- Best Screenwriter

- 31st Golden Rooster Awards[8]

- Nominated – Best Cinematography (Sun Ming)

- Nominated – Best Sound (Chao Jun)

- Nominated – Best Art Direction (Wu Ming)

- Nominated – Best Original Music Score (Wang Xiaofeng)

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Review: Xuan Zang (2016)" (in Chinese (China)). Sino-Cinema 《神州电影》. 10 June 2016. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "India-China ink maiden film co-production deal". Indian television.com. 15 May 2015. Archived from the original on 11 December 2016.

- ^ a b c "大唐玄奘 (Xuan Zang)" (in Chinese (China)). ChinaBoxOffice. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Crossing the wall: What it took to produce the first India-China joint film, Xuanzang, the story of legendary traveler and monk Hiuen Tsang". India Today. 20 May 2016. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Xuanzang". Encyclopedia Britannica. 1 January 2023. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Rahman, Abid (5 October 2016). "Oscars: China Selects 'Xuan Zang' for Foreign-Language Category". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ a b "第十二屆中美電影節星光熠熠 (The 12th China-US Film Festival is star-studded)" (in Traditional Chinese). EDI Media Inc. 2016. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ a b "金鸡奖提名 (Golden Rooster Award nominations)" (in Chinese (China)). Ifeng.com. 16 August 2017. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Xuan Zang (2016 Film) – the Man who inspired Journey to the West". Chasing Dramas: All Things Chinese Dramas. 21 July 2022. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Xuan Zang". Chinese Drama Info. 2016. Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "First India-China movie 'Xuanzang' to hit screens this month". Hindustan Times. 8 April 2016. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "《大唐玄奘》火焰山开机 黄晓明为戏吃素 ("Xuan Zang of the Tang dynasty" premieres at Flaming Mountain; Huang Xiaoming becomes a vegetarian for the film)" (in Chinese (China)). 新浪 (Sina.com). 8 June 2015. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Li, Rongxi 1995, pg. 3.

- ^ Wriggins 2004, pg. 6.

- ^ Wriggins 2004, pp. 12-13, 16-17.

- ^ Wriggins 2004, pg. 13.

- ^ Li, Rongxi 1995, pg. 156.

- ^ Wriggins 2004, pp. 165-166.

- ^ Frater, Patrick (1 May 2016). "China Box Office: 'Book of Love' Wins May Day Weekend". Variety. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

Biographical Sources edit

- Li, Rongxi, trans. (1995). A Biography of the Tripiṭaka Master of the Great Ci'en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty by Sramana Huili and Shi Yancong. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. Berkeley, California. ISBN 1-886439-00-1 (a recent, full translation)

- Wriggins, Sally Hovey (2004). The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-6599-6.

External links edit

- Xuanzang at IMDb

- Xuan Zang at the Hong Kong Movie DataBase