Summary

Yungaburra is a rural town and locality in the Tablelands Region, Queensland, Australia.[3][4] In the 2016 census, the locality of Yungaburra had a population of 1,239 people.[1]

| Yungaburra Queensland | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

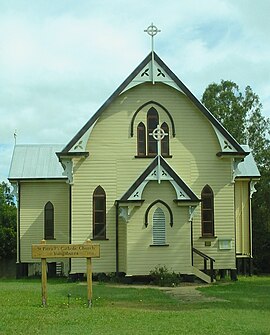

St Patrick's Catholic Church (built 1914) | |||||||||||||||

Yungaburra | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 17°16′08″S 145°34′58″E / 17.2688°S 145.5827°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 1,239 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 72.88/km2 (188.8/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1886[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 4884 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 750 m (2,461 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 17.0 km2 (6.6 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10:00) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | |||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | Tablelands Region | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Hill | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Kennedy | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Geography edit

Yungaburra is on the Atherton Tableland in Far North Queensland.

The landscape around Yungaburra has been shaped by millennia of volcanic activity. The most recent eruptions were approximately 10,000 years ago. Notable geological features nearby include:[citation needed]

- Seven Sisters and Mount Quincan are volcanic cones.[citation needed]

- Lake Eacham (Yidyam) and Lake Barrine are lakes inside volcanic craters.[citation needed]

- Mount Hypipamee Crater is a diatreme (crater).[citation needed]

- Tinaroo Dam submerged the old town of Kulara is visible, on whose cricket-pitch, when drought conditions drastically lower the water-level, locals play cricket matches.[5]

History edit

Prior to European settlement, the area around Yungaburra was inhabited by about sixteen different indigenous groups, among them the Ngatjan, with the custodians being Yidinji people and neighbouring Ngajanji people. The Queensland police and native troops carried out extensive massacres in the area to rid it of blacks. In one incident in 1884, at Skull Pocket just north of the town, a group of Yidinji were surrounded at night, and at dawn mowed down after they fled on hearing the first shot. The children were brained or stabbed to death by native troopers.[6]

In the early 1880s, the area around Allumbah Pocket was used as an overnight stop for miners travelling west from the coast. In 1886 the land was surveyed, and in 1891 settlers moved in.[citation needed]

Allumbah State School opened on 7 June 1909. In 1911 it was renamed Yungaburra State School.[7]

In 1910, the railway arrived and the railway station was named Yungaburra by the Queensland Railways Department. The town was then renamed Yungaburra, to avoid confusion with another town called Allumbah. The name Yungaburra comes from the local Yidiny word janggaburru, denoting the Queensland silver ash (Flindersia bourjotiana).[3][8]

By 1911, indigenous numbers had fallen to 20% of the pre-settlement population due to disease, conflict with settlers and loss of habitat.[citation needed]

In January 1911, residents of Kulara (a small town to the north of Yungaburra) began lobbying for a school, claiming there were 42 children in the district.[9] Kulara State School opened on 17 June 1912. It closed on 1 September 1958, when the Tinaroo Dam began to fill, inundating the town.[7] However, being on higher ground, the school building was not flooded and became a private residence at 85 Backshall Road (now in Barrine, 17°14′39″S 145°34′59″E / 17.24420°S 145.58306°E).[10][11][12]

In 2006, the Atherton Tableland region was damaged by Cyclone Larry, rated as Category 4 cyclone on the Australian scale. Of the 19 heritage listed sites in Yungaburra, only the roofs of the community hall, police station and one of the bush cottages were badly damaged, as were the front of the Yungaburra Butchery and Gem Gallery sign. The town was restored very quickly; little evidence of the cyclone is visible.[citation needed]

At the 2006 census, the town of Yungaburra had a population of 932.[13]

At the 2011 census, the locality of Yungaburra had a population of 1,116 people.[14]

In the 2016 census, the locality of Yungaburra had a population of 1,239 people.[1]

Heritage listings edit

Yungaburra has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

- 27 Atherton Road: Bank of New South Wales[15]

- 6–10 Cedar Street: Yungaburra Court House[16]

- 7–9 Cedar Street: 7-9 Cedar Street, Yungaburra[17]

- 12 Cedar Street: Residence[18]

- 15–17 Cedar Street: Yungaburra Post Office[19]

- 16–20 Cedar Street: Williams' House[20]

- 19 Cedar Street: Yungaburra Community Centre[21]

- 32 Cedar: Billy Madrid's House[22]

- 34 Cedar Street: Barber's Shop, Yungaburra[23]

- Curtain Fig Tree Road: Curtain Fig Tree[24]

- 7 Eacham Road: St Marks Anglican Church[25]

- 25–33 Eacham Road: Cairns Plywood Pty Ltd Sawmill Complex[26]

- 20 Gillies Highway: Eden House Restaurant[27]

- 2 Kehoe Place: Butchers Shop[28]

- 6–8 Kehoe Place: Lake Eacham Hotel[29]

- 7 Mulgrave Road: Allumbah[30]

- 4 Oak Street: Residence[31]

- 1 Penda Street: St Patricks Catholic Church[32]

- on the shores of Lake Tinaroo, the Afghanistan Avenue of Honour[33]

-

Curtain Fig Tree

-

Lake Eacham Hotel

Amenities edit

Yungaburra's economy today revolves around tourism, and the town contains a primary school, post office, library/telecentre and a range of businesses and services for the use of residents and visitors. Other facilities include a tennis court and a bowling club. The town has 18 Heritage Listed buildings, and is the largest National Trust village in Queensland. The Yungaburra Markets, held on the fourth Saturday of each month, are one of the largest in Far North Queensland, and each year around the end of October, Yungaburra holds the two-day Yungaburra Folk Festival, featuring concerts from Australian (and sometimes international) folk musicians.[citation needed]

Yungaburra is also the site of the war memorial to soldiers lost, opened 22 June 2013.[citation needed]

There is a network of walking tracks around the town including Peterson's Creek.[citation needed]

Yungaburra has a library at Maud Kehoe Park operated by the Tablelands Regional Council.[34]

The Yungaburra branch of the Queensland Country Women's Association meets at the QCWA Hall on the corner of Cedar Street and the Gillies Highway.[35]

Our Lady of Consolation and St Patrick's Catholic Church is at 3 Mulgrave Road. It is within the Atherton Parish of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Cairns.[36]

Education edit

Yungaburra State School is a government primary (Prep–6) school for boys and girls at 4 Maple Street (17°16′22″S 145°35′09″E / 17.2729°S 145.5857°E).[37][38] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 213 students with 18 teachers (12 full-time equivalent) and 14 non-teaching staff (9 full-time equivalent).[39] In 2018, the school had an enrolment of 224 students with 20 teachers (15 full-time equivalent) and 15 non-teaching staff (8 full-time equivalent).[40]

There is no secondary school in Yungaburra. The nearest government secondary schools are Atherton State High School in Atherton to the west and Malanda State High School in Malanda to the south.[41]

Tourism edit

Allumbah Pocket is a picnic area on Peterson's Creek which runs past Yungaburra. It is the centre for a series of walking tracks along the creek. Tracks lead to Frawley's Pool, a popular swimming hole and picnic area, then further to Yungaburra's historical train bridge. In the opposite direction there is a track to the platypus viewing deck. Aside from this all of the tracks are relatively easy and short enough for anyone to do. The site is dedicated to Geoff Tracy, a local renowned environmentalist who died in 2004.[citation needed]

Yungaburra has access to the southern arm of Lake Tinaroo which is popular for fishing, canoeing, sailing, swimming, water-skiing and camping. The other main places to get to Tinaroo are Kairi and the township of Tinaroo.[citation needed]

The Curtain Fig Tree, which is just out of Yungaburra, is a giant rainforest fig tree with roots hanging down, giving it the appearance of curtains. There is a short boardwalk around the tree.[citation needed]

Lake Barrine and Lake Eacham are crater lakes, formed from volcanoes. Lake Eacham is popular for swimming and Lake Barrine has a teahouse and gift shop as well as cruises around the lake however is unsuitable for swimming due to the cruise boats. Both lakes have walking tracks around them. Lake Barrine's track is 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) and Lake Eacham's is 3 kilometres (1.9 mi).[citation needed]

Notable people edit

Notable people from or who have lived in Yungaburra include:

- George Alfred Duffy (1887–1941), Member of the Queensland Legislative Assembly for Eacham

- Jim Petrich, businessman, grazing industry leadership, and Cape York economic development

- Edward Stratten Williams (1921–1999), judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Yungaburra (SSC)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ "History of Yungaburra". Archived from the original on 29 October 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Yungaburra – town in Tablelands Region (entry 38803)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Yungaburra – locality in Tablelands Region (entry 48957)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Geiger, Dominic (20 December 2016). "Cricket match planned for middle of dry Tinaroo dam". Cairns Post. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ Bottoms, Timothy (2013). Conspiracy of Silence (PDF). Allen & Unwin. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-1-743-31382-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ a b Queensland Family History Society (2010), Queensland schools past and present (Version 1.01 ed.), Queensland Family History Society, ISBN 978-1-921171-26-0

- ^ Dixon, Robert M. W. (1991). Words of Our Country: Stories, place names and vocabulary in Yidiny, the Aboriginal language of the Cairns-Yarrabam region (PDF). University of Queensland Press. p. 25. ISBN 0 7022 2360 3.

- ^ "COUNTRY NEWS". The Evening Telegraph. No. 2994. Queensland, Australia. 31 January 1911. p. 4. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Queensland Two Mile series sheet 2m404" (Map). Queensland Government. 1943. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Kulara reunion event". The Express Newspaper. 1 July 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "The town that disappeared under water leaving only a school behind". ABC News. 13 August 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Yungaburra (Urban Centre/Locality)". 2006 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (31 October 2012). "Yungaburra (SSC)". 2011 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ "27 Atherton Road, Yungaburra (entry 600468)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Court House, Police Station and Residence (entry 600477)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "7-9 Cedar Street, Yungaburra (entry 600480)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Residence (entry 600476)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Yungaburra Post Office and residence (entry 600471)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Residence 16-20 Cedar Street (entry 600472)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Community Centre (entry 600479)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Special Glass Co. Shop (entry 600478)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Burra Inn Restaurant (entry 600470)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "The Curtain Fig Tree (entry 602734)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "St Marks Anglican Church (entry 600484)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Cairns Plywood Pty Ltd Sawmill Complex (entry 600481)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Eden House Restaurant (entry 600467)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Butchers Shop (entry 600482)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Lake Eacham Hotel (entry 600473)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Allumbah (entry 600486)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Residence (entry 600487)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "St Patricks Catholic Church (entry 600488)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ Nancarrow, Kirsty; Ford, Elaine (7 November 2014). "Thousands attend opening of Avenue of Honour, a memorial to diggers killed in Afghanistan". ABC News. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ "Yungaburra Library". plconnect.slq.qld.gov.au. State Library of Queensland. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Branch Locations". Queensland Country Women's Association. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Atherton Parish". Roman Catholic Diocese of Cairns. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ "State and non-state school details". Queensland Government. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ "Yungaburra State School". Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "ACARA School Profile 2017". Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ "ACARA School Profile 2018". Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Queensland Globe". State of Queensland. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

External links edit

- Yungaburra.com

- Atherton Tablelands Travel Guide

- "Yungaburra". Queensland Places. Centre for the Government of Queensland, University of Queensland.

- "Town map of Yungaburra". Queensland Government. 1980.

- Yungaburra Centenary of Railway and Lake Eacham Hotel 2010 Digital Story, State Library of Queensland