Summary

Academic art, academicism, or academism, is a style of painting and sculpture produced under the influence of European academies of art, usually used of work produced in the 19th century, after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. In this period the standards of the French Académie des Beaux-Arts were very influential, combining elements of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, with Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres a key figure in the formation of the style in painting. Later painters who tried to continue the synthesis included William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Thomas Couture, and Hans Makart among many others. In this context it is often called "academism", "academicism", "art pompier" (pejoratively), and "eclecticism", and sometimes linked with "historicism" and "syncretism." Academic art is closely related to Beaux-Arts architecture, which developed in the same place and holds to a similar classicizing ideal.

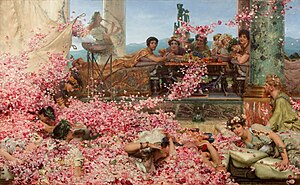

The Birth of Venus by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1879); Phaedra by Alexandre Cabanel (1880); The Roses of Heliogabalus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1888) |

Although production continued into the 20th century, the style had become vacuous, and was strongly rejected by the artists of set of new art movements, of which Impressionism was one of the first. By World War I, it had fallen from favour almost completely with critics and buyers, returning somewhat to favour at the end of the 20th century.

Although smaller works such as portraits, landscapes and still-lifes were often produced (and often sold more easily), the movement and the contemporary public and critics most valued large history paintings showing moments from narratives that were very often taken from old or exotic areas of history, though less often the traditional religious narratives. Orientalist art was a major branch, with many specialist painters, as had scenes from classical antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Origins and theoretical foundations edit

The first art academies in Renaissance Italy edit

The first academy of art was founded in Florence by Cosimo I de' Medici, on 13 January 1563, under the influence of the architect Giorgio Vasari, who called it the Accademia e Compagnia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy and Company for the Arts of Drawing) as it was divided in two different operative branches. While the company was a kind of corporation that every working artist in Tuscany could join, the academy comprised only the most eminent artists of Cosimo's court, and had the task of supervising the whole artistic production of the Medicean state. In this institution, students learned the "arti del disegno" (a term coined by Vasari) and heard lectures on anatomy and geometry.[1][2][3]

Another academy, the Accademia di San Luca (named after the patron saint of painters, St. Luke), was founded about a decade later in Rome. It served an educational function and was more concerned with art theory than the Florentine one.[4] In 1582, Annibale Carracci opened his very influential Accademia dei Desiderosi (Academy of the Desirous) in Bologna without official support; in some ways, this was more like a traditional artist's workshop, but that he felt the need to label it as an "academy" demonstrates the attraction of the idea at the time.[5]

Standardization: French academicism and visual arts edit

The Accademia di San Luca later served as the model for the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture founded in France in 1648, and which later became the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture was founded in an effort to distinguish artists "who were gentlemen practicing a liberal art" from craftsmen, who were engaged in manual labor. This emphasis on the intellectual component of artmaking had a considerable impact on the subjects and styles of academic art.[6][7][8]

After the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture was reorganized in 1661 by Louis XIV, whose aim was to control all the country's artistic activity,[9] a controversy occurred among the members that dominated artistic attitudes for the rest of the century. This "battle of styles" was a conflict over whether Peter Paul Rubens or Nicolas Poussin was a suitable model to follow. Followers of Poussin, called "poussinistes", argued that line (disegno) should dominate art, because of its appeal to the intellect, while followers of Rubens, called "rubenistes", argued that color (colore) should dominate art, because of its appeal to emotion.[10] The debate was revived in the early 19th century, under the movements of Neoclassicism typified by the art of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, and Romanticism typified by the artwork of Eugène Delacroix. Debates also occurred over whether it was better to learn art by looking at nature, or to learn by looking at the artistic masters of the past.[11]

Transformations and diffusion of the French model edit

Academies using the French model formed throughout Europe, and imitated the teachings and styles of the French Académie: Nuremberg (1674), Berlin (1697), Vienna (1705), Saint Petersburg (1724), Stockholm (1735), Copenhagen (1738) and Madrid (1752). In England, this was the Royal Academy, which was founded in 1768 with a mission "to establish a school or academy of design for the use of students in the arts".[12][13]

The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1754, may be taken as a successful example in a smaller country, which achieved its aim of producing a national school and reducing the reliance on imported artists. The painters of the Danish Golden Age of roughly 1800–1850 were nearly all trained there, and drawing on Italian and Dutch Golden Age paintings as examples, many returned to teach locally.[14] The history of Danish art is much less marked by tension between academic art and other styles than is the case in other countries.[citation needed]

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the model expanded to America, with the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico being founded in 1783, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the United States in 1805,[15] and the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Brazil in 1826.[16] Meanwhile, back in Italy, another major center of irradiation appeared, Venice, launching the tradition of urban views and "capriccios", fantasy landscape scenes populated by ancient ruins, which became favorites of noble travelers on the Grand Tour.[15]

Development of the academic style edit

Stylistic trends and hierarchy of genres edit

Since the onset of the Poussiniste-Rubeniste debate, many artists worked between the two styles. In the 19th century, in the revived form of the debate, the attention and the aims of the art world became to synthesize the line of Neoclassicism with the color of Romanticism. One artist after another was claimed by critics to have achieved the synthesis, among them Théodore Chassériau, Ary Scheffer, Francesco Hayez, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, and Thomas Couture. William-Adolphe Bouguereau, a later academic artist, commented that the trick to being a good painter is seeing "color and line as the same thing." Thomas Couture promoted the same idea in a book he authored on art method—arguing that whenever one said a painting had better color or better line it was nonsense, because whenever color appeared brilliant it depended on line to convey it, and vice versa; and that color was really a way to talk about the "value" of form.

Another development during this period included adopting historical styles in order to show the era in history that the painting depicted, called historicism. This is best seen in the work of Baron Jan August Hendrik Leys, a later influence on James Tissot. It is also seen in the development of the Neo-Grec style. Historicism is also meant to refer to the belief and practice associated with academic art that one should incorporate and conciliate the innovations of different traditions of art from the past.

The art world also grew to give increasing focus on allegory in art. Theories of the importance of both line and color asserted that through these elements an artist exerts control over the medium to create psychological effects, in which themes, emotions, and ideas can be represented. As artists attempted to synthesize these theories in practice, the attention on the artwork as an allegorical or figurative vehicle was emphasized. It was held that the representations in painting and sculpture should evoke Platonic forms, or ideals, where behind ordinary depictions one would glimpse something abstract, some eternal truth. Hence, Keats' famous musing "Beauty is truth, truth beauty." The paintings were desired to be an "idée", a full and complete idea. Bouguereau is known to have said that he would not paint "a war", but would paint "War." Many paintings by academic artists are simple nature allegories with titles like Dawn, Dusk, Seeing, and Tasting, where these ideas are personified by a single nude figure, composed in such a way as to bring out the essence of the idea.

The trend in art was also towards greater idealism, which is contrary to realism, in that the figures depicted were made simpler and more abstract—idealized—in order to be able to represent the ideals they stood in for. This would involve both generalizing forms seen in nature, and subordinating them to the unity and theme of the artwork.

Because history and mythology were considered as plays or dialectics of ideas, a fertile ground for important allegory, using themes from these subjects was considered the most serious form of painting. A hierarchy of genres, originally created in the 17th century, was valued, where history painting—classical, religious, mythological, literary, and allegorical subjects—was placed at the top, next genre painting, then portraiture, still-life, and landscape.[17][18] History painting was also known as the "grande genre." Paintings of Hans Makart are often larger than life historical dramas, and he combined this with a historicism in decoration to dominate the style of 19th-century Vienna culture. Paul Delaroche is a typifying example of French history painting.

All of these trends were influenced by the theories of the philosopher Hegel, who held that history was a dialectic of competing ideas, which eventually resolved in synthesis.

Apotheosis: Parisian salons and further influence edit

Towards the end of the 19th century, academic art had saturated European society. Exhibitions were held often, with the most popular exhibition being the Paris Salon and beginning in 1903, the Salon d'Automne. These salons were large scale events that attracted crowds of visitors, both native and foreign. As much a social affair as an artistic one, 50,000 people might visit on a single Sunday, and as many as 500,000 could see the exhibition during its two-month run. Thousands of pictures were displayed, hung from just below eye level all the way up to the ceiling in a manner now known as "Salon style." A successful showing at the salon was a seal of approval for an artist, making his work saleable to the growing ranks of private collectors. Bouguereau, Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Léon Gérôme were leading figures of this art world.[19][20]

During the reign of academic art, the paintings of the Rococo era, previously held in low favor, were revived to popularity, and themes often used in Rococo art such as Eros and Psyche were popular again. The academic art world also admired Raphael, for the ideality of his work, in fact preferring him over Michelangelo.

Academic art in Poland flourished under Jan Matejko, who established the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts. Many of these works can be seen in the Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art at Sukiennice in Kraków.

Academic art not only held influence in Western Europe and the United States, but also extended its influence to other countries. The artistic environment of Greece, for instance, was dominated by techniques from Western academies from the 17th century onward: this was first evident in the activities of the Ionian School, and later became especially pronounced with the dawn of the Munich School. This was also true for Latin American nations, which, because their revolutions were modeled on the French Revolution, sought to emulate French culture. An example of a Latin American academic artist is Ángel Zárraga of Mexico.

Academic training edit

Young artists spent four years in rigorous training. In France, only students who passed an exam and carried a letter of reference from a noted professor of art were accepted at the academy's school, the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts). Drawings and paintings of the nude, called "académies", were the basic building blocks of academic art and the procedure for learning to make them was clearly defined. First, students copied prints after classical sculptures, becoming familiar with the principles of contour, light, and shade. The copy was believed crucial to the academic education; from copying works of past artists one would assimilate their methods of art making. To advance to the next step, and every successive one, students presented drawings for evaluation.

If approved, they would then draw from plaster casts of famous classical sculptures. Only after acquiring these skills were artists permitted entrance to classes in which a live model posed. Painting was not taught at the École des Beaux-Arts until after 1863. To learn to paint with a brush, the student first had to demonstrate proficiency in drawing, which was considered the foundation of academic painting. Only then could the pupil join the studio of an academician and learn how to paint. Throughout the entire process, competitions with a predetermined subject and a specific allotted period of time measured each student's progress.

The most famous art competition for students was the Prix de Rome, whose winner was awarded a fellowship to study at the Académie française's school at the Villa Medici in Rome for up to five years. To compete, an artist had to be of French nationality, male, under 30 years of age, and single. He had to have met the entrance requirements of the École des Beaux-Arts and have the support of a well-known art teacher. The competition was grueling, involving several stages before the final one, in which 10 competitors were sequestered in studios for 72 days to paint their final history paintings. The winner was essentially assured a successful professional career.

As noted, a successful showing at the Salon, the exhibition of work founded by the École des Beaux-Arts, was a seal of approval for an artist. Artists petitioned the hanging committee for optimal placement "on the line", or at eye level. After the exhibition opened, artists complained if their works were "skyed", or hung too high. The ultimate achievement for the professional artist was election to membership in the Académie française and the right to be known as an academician.

Women artists edit

One effect of the move to academies was to make training more difficult for women artists, who were excluded from most academies until the last half of the 19th century.[a][22][23] This was partly because of concerns over the perceived impropriety presented by nudity during training.[22] In France, for example, the powerful École des Beaux-Arts had 450 members between the 17th century and the French Revolution, of which only 15 were women. Of those, most were daughters or wives of members. In the late 18th century, the French Academy resolved not to admit any women at all.[b] As a result, there are no extant large-scale history paintings by women from this period, though some women like Marie-Denise Villers and Constance Mayer made their name in other genres such as portraiture.[25][26][27][28]

In spite of this, there were important steps forward for female artists. In Paris, the Salon became open to non-Academic painters in 1791, allowing women to showcase their work in the prestigious annual exhibition. Additionally, women were more frequently being accepted as students by famous artists such as Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Baptiste Greuze.[29]

The emphasis in academic art on studies of the nude remained a considerable barrier for women studying art until the 20th century, both in terms of actual access to the classes and in terms of family and social attitudes to middle-class women becoming artists.[30]

Criticism and legacy edit

Academic art was first criticized for its use of idealism, by Realist artists such as Gustave Courbet, as being based on idealistic clichés and representing mythical and legendary motives while contemporary social concerns were being ignored. Another criticism by Realists was the "false surface" of paintings—the objects depicted looked smooth, slick, and idealized—showing no real texture. The Realist Théodule Ribot worked against this by experimenting with rough, unfinished textures in his painting.

Stylistically, the Impressionists, who advocated quickly painting outdoors exactly what the eye sees and the hand puts down, criticized the finished and idealized painting style. Although academic painters began a painting by first making drawings and then painting oil sketches of their subject, the high polish they gave to their drawings seemed to the Impressionists tantamount to a lie. After the oil sketch, the artist would produce the final painting with the academic "fini", changing the painting to meet stylistic standards and attempting to idealize the images and add perfect detail. Similarly, perspective is constructed geometrically on a flat surface and is not really the product of sight; Impressionists disavowed the devotion to mechanical techniques.

Realists and Impressionists also defied the placement of still-life and landscape at the bottom of the hierarchy of genres. Most Realists and Impressionists and others among the early avant-garde who rebelled against academism were originally students in academic ateliers. Claude Monet, Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, and even Henri Matisse were students under academic artists.

As modern art and its avant-garde gained more power, academic art was further denigrated, and seen as sentimental, clichéd, conservative, non-innovative, bourgeois, and "styleless." The French referred derisively to the style of academic art as L'art pompier (pompier means "fireman") alluding to the paintings of Jacques-Louis David (who was held in esteem by the academy), which often depicted soldiers wearing fireman-like helmets.[31] It also suggests half-puns in French with pompéien ("from Pompeii") and pompeux ("pompous").[32][33] The paintings were called "grandes machines", which were said to have manufactured false emotion through contrivances and tricks.

This denigration of academic art reached its peak through the writings of art critic Clement Greenberg who stated that all academic art is "kitsch." Other artists, such as the Symbolist painters and some of the Surrealists, were kinder to the tradition.[citation needed] As painters who sought to bring imaginary vistas to life, these artists were more willing to learn from a strongly representational tradition. Once the tradition had come to be looked on as old-fashioned, the allegorical nudes and theatrically posed figures struck some viewers as bizarre and dreamlike.

With the goals of Postmodernism in giving a fuller, more sociological and pluralistic account of history, academic art has been brought back into history books and discussion. Since the early 1990s, academic art has even experienced a limited resurgence through the Classical Realist atelier movement.[34] Additionally, the art is gaining a broader appreciation by the public at large, and whereas academic paintings once would only fetch a few hundreds of dollars in auctions, some now fetch millions.[35]

Major artists edit

Austria edit

Belgium edit

Brazil edit

Canada edit

Croatia edit

Czech Republic edit

Estonia edit

Finland edit

France edit

|

Germany edit

Hungary edit

India edit

Ireland edit

Italy edit

Latvia edit

Netherlands edit

Peru edit

Poland edit

Russia edit

Serbia edit

Slovenia edit

Spain edit

Sweden edit

Switzerland edit

United Kingdom edit

Uruguay edit

|

Gallery edit

-

The Rape of the Sabine Women, by Nicolas Poussin, c. 1634–35, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

-

Egypt Saved by Joseph, by Alexandre-Denis Abel de Pujol, 1827, oil on canvas, ceiling of a room in the Louvre Palace, Paris[37]

-

The Assassination of the Duke of Guise at the Château de Blois in 1588, by Paul Delaroche, 1834, oil on canvas, Musée Condé, Chantilly, France

-

Condé and Mazarin, by Eugène Devéria, c. 1835, oil on canvas, Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans, Orléans, France

-

The Romans in their Decadence, by Thomas Couture, 1844–1847, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay, Paris[38]

-

Call of the Last Victims of Terror, by Charles Louis Müller, 1850, oil on canvas, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Carcassonne, Carcassonne, France

-

The Alchemist, by William Fettes Douglas, 1853, oil on canvas, Victoria and Albert Museum, London[39]

-

The Empress Eugenie Surrounded by her Ladies in Waiting, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1855, oil on canvas, Château de Compiègne, Compiègne, France[40]

-

Rehearsal of The Flute Player and The Woman of Diomede at the home of Prince Napoleon in the atrium of his Pompeian house, by Gustave Boulanger, 1861, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay

-

Lost Illusions, by Léon Dussart and Charles Gleyre, 1865–1867, oil on canvas, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, US

-

The Death of Orpheus, by Émile Lévy, 1866, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay[41]

-

The Discovery of Pulque, by Jose Maria Obregon, 1869, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City

-

Pollice Verso (Thumbs Down), by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1872, oil on canvas, Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, Arizona, USA

-

The Triumph of Beauty, Charmed by Music, amidst the Muses and the Hours of the Day, designed for the ceiling of the auditorium of the Palais Garnier, by Jules-Eugène Lenepveu, 1872, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay

-

Moonlit Dreams, by Gabriel Ferrier, 1874, oil on canvas, private collection

-

-

The Excommunication of Robert the Pious, by Jean-Paul Laurens, 1875, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay[43]

-

The Babylonian Marriage Market, by Edwin Long, 1875, oil on canvas, Royal Holloway, University of London

-

-

Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners, by Alexandre Cabanel, 1887, oil on canvas, private collection[45]

-

The Renaissance of Letters, by Pierre-Victor Galland, 1888, oil on canvas, Musée départemental de l'Oise, Beauvais, France

-

Ulysses and the Sirens, by John William Waterhouse, 1891, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia[46]

-

The Garden of the Hesperides, by Frederic Leighton, c. 1892, oil on canvas, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Wirral, the UK[47]

-

Reverie (In the Days of Sappho), by John William Godward, 1904, oil on canvas, Getty Center

Notes edit

- ^ The Royal Academy did not admit women until 1861, despite having two, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser, among its founding members, as evidenced by the group portrait of The Academicians of the Royal Academy by Johan Zoffany, now in the Royal Collection. In it, only the men of the Academy are assembled in a large artist studio, together with nude male models. For reasons of decorum given the nude models, the two women are not shown as present, but as portraits on the wall instead.[21]

- ^ It was only in 1897 that the École des Beaux-Arts officially accepted women. They were then authorized to work in the galleries, to sit the entrance exams and to take painting and sculpture classes in a separate studio from the men. This date of 1897 initially concerned the painting section, but was extended to the architecture section in 1898 and the sculpture section in 1899. In 1900, women were given access to the studios, which allowed them to paint live models.[24]

References edit

- ^ Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (in Italian). Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo: Direzione Generale per le Biblioteche, gli Istituti Culturali e il Diritto d'Autore. Accessed October 2014.

- ^ Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Santi di Tito and the Florentine Academy: Solomon Building the Temple in the Capitolo of the Accademia del Disegno (1570–71), Apollo CLV, 480 (February 2002): pp. 31–39.

- ^ Adorno, Francesco. (1983). Accademie e istituzioni culturali a Firenze (in Italian). Florence: Olschki.

- ^ Carl Goldstein (1996). Teaching Art: Academies and Schools from Vasari to Albers. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55988-X.

- ^ Claudio Strinati, Annibale Carracci (in Italian), Firenze, Giunti Editore, 2001 ISBN 88-09-02051-0

- ^ Testelin 1853, p. 22–36.

- ^ Montaiglon & Cornu 1875, p. 7–10.

- ^ Dussieux et al. 1854, p. 216.

- ^ Janson, H.W. (1995). History of Art, 5th edition, revised and expanded by Anthony F. Janson. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0500237018

- ^ Driskel, Michael Paul. Representing belief: religion, art, and society in nineteenth-century France, Volume 1991. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992. pp. 47-49

- ^ Tanner, Jeremy. The sociology of art: a reader. Routledge, 2003. p. 5

- ^ Hodgson & Eaton 1905, p. 11.

- ^ John Harris, Sir William Chambers Knight of the Polar Star, Chapter 11: The Royal Academy, 1970, A. Zwemmer Ltd

- ^ J. Wadum, M. Scharff, K. Monrad, "Hidden Drawings from the Danish Golden Age. Drawing and underdrawing in Danish Golden Age views from Italy" in SMK Art Journal 2006, ed. Peter Nørgaard Larsen. Statens Museum for Kunst, 2007.

- ^ a b Kemp, Martín. The Oxford history of Western art. Oxford University Press US, 2000, p. 218–219

- ^ Eulálio, Alexandre. O Século XIX. In Tradição e Ruptura. Síntese de Arte e Cultura Brasileiras. São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 1984–85, p. 121

- ^ Hierarchy of the Genres. Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art

- ^ Kemp, Martín. The Oxford history of Western art. Oxford University Press US, 2000. pp. 218-219

- ^ Patricia Mainardi: The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic, Cambridge University Press, 1993

- ^ Fae Brauer, Rivals and Conspirators: The Paris Salons and the Modern Art Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, 2013

- ^ Zoffany, Johan (1771–1772). "The Royal Academicians". The Royal Collection. Retrieved 20 March 2007.

- ^ a b Myers, Nicole. "Women Artists in Nineteenth–Century France". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Levin, Kim (November 2007). "Top Ten ARTnews Stories: Exposing the Hidden 'He'". ArtNews.

- ^ Marina Sauer, L'entrée des femmes à l'Ecole des Beaux-Arts, 1880-1923 (in French), Paris, École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 1990, p. 10

- ^ Harris, Ann Sutherland and Linda Nochlin. Women Artists: 1550–1950. Alfred A. Knopf, New York (1976). p. 217.

- ^ Petteys, Chris, Dictionary of Women Artists, G K Hill & Co. publishers, 1985

- ^ Delia Gaze. Concise Dictionary of Women Artists. Routledge; 3 April 2013. ISBN 978-1-136-59901-9. p. 665.

- ^ Germaine Greer. The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work. Tauris Parke Paperbacks; 2 June 2001. ISBN 978-1-86064-677-5. p. 36–37.

- ^ Stranahan, C.H., "A History of French Painting: An account of the French Academy of Painting, its salons, schools of instructions and regulations", Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1896

- ^ Nochlin, Linda. "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" (PDF). Department of Art History, University of Concordia.

- ^ Louis-Marie Descharny, L'Art pompier (in French), 1998, p. 12

- ^ Louis-Marie Descharny, L'Art pompier (in French), 1998, p. 14

- ^ Pascal Bonafoux, Dictionnaire de la peinture par les peintres (in French), p. 238-239, Perrin, Paris, 2012 ISBN 978-2-262-032784 (read online).

- ^ Panero, James: "The New Old School", The New Criterion, Volume 25, September 2006, p. 104.

- ^ Esterow, Milton (1 January 2011). "From 'Riches to Rags to Riches'". ArtNews. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Academism of the 19th Century". www.galerijamaticesrpske.rs. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. p. 110. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- ^ Graham-Nixon, Andrew (2023). art THE DEFINITIVE VISUAL HISTORY. DK. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-2416-2903-1.

- ^ Elizabeth, S. (2020). The Art of the Occult - A Visual Sourcebook for the Modern Mystic. White Lion Publishing. p. 73. ISBN 978 0 7112 4883 0.

- ^ Cumming, Robert (2020). ART a visual history. DK. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-2414-3741-4.

- ^ Christophe, Averty (2020). Orsay. Éditions Place des Victories. p. 40. ISBN 978-2-8099-1770-3.

- ^ Cumming, Robert (2020). ART a visual history. DK. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-2414-3741-4.

- ^ Christophe, Averty (2020). Orsay. Éditions Place des Victories. p. 41. ISBN 978-2-8099-1770-3.

- ^ Elizabeth, S. (2020). The Art of the Occult - A Visual Sourcebook for the Modern Mystic. White Lion Publishing. p. 215. ISBN 978 0 7112 4883 0.

- ^ Cumming, Robert (2020). ART a visual history. DK. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-2414-3741-4.

- ^ Elizabeth, S. (2022). The Art of Darkness. White Lion Publishing. p. 199. ISBN 978-0 7112-6920-0.

- ^ Cumming, Robert (2020). ART a visual history. DK. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-2414-3741-4.

Bibliography edit

- Dussieux, Louis Etienne; Soulié, Eudore; Mantz, Paul; Montaiglon, Anatole de (1854). Mémoires inédits sur la vie et les ouvrages des membres de l'Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture : publiés d'après les manuscrits conservés à l'Ecole impériale des beaux-arts [Unpublished memoirs on the life and works of members of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture: published from the manuscripts kept at the Imperial School of Fine Arts] (in French). Vol. I. Paris: J.-B. Dumoulin. (Vol. 1 and 2 at Internet Archive, Vol. 1 and 2 at Gallica.)

- Hodgson, J. E.; Eaton, Fred A. (1905). The Royal academy and its members 1768–1830. London: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Montaiglon, Anatole de; Cornu, M. Paul (1875). Table Procès-Verbaux de l'Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, 1648-1793 [Table Minutes of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, 1648-1793] (in French). Vol. I. Paris: J. Baur.

- Testelin, Henri (1853). Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire de l'Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, depuis 1648 jusqu'en 1664 [Memories to serve in the history of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture from 1648 until 1664] (in French). Vol. I. Paris: P. Jannet.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading edit

- Art and the Academy in the Nineteenth Century. (2000). Denis, Rafael Cardoso & Trodd, Colin (Eds). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2795-3

- L'Art-Pompier (1998). Lécharny, Louis-Marie, Que sais-je? (in French). Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-049341-6

- L'Art pompier: immagini, significati, presenze dell'altro Ottocento francese (1860–1890) (in French). (1997). Luderin, Pierpaolo, Pocket library of studies in art, Olschki. ISBN 88-222-4559-8

External links edit

- Media related to Academic art at Wikimedia Commons